Understanding Threatened Species: A Call to Action for Earth’s Biodiversity

The natural world is a tapestry woven with countless species, each playing a vital role in the intricate web of life. Yet, this tapestry is fraying at an alarming rate, with many species facing an uncertain future. The term “threatened species” often conjures images of majestic animals on the brink, but it encompasses a far broader and more complex reality. Understanding what makes a species threatened, why it matters, and what can be done is crucial for safeguarding Earth’s precious biodiversity.

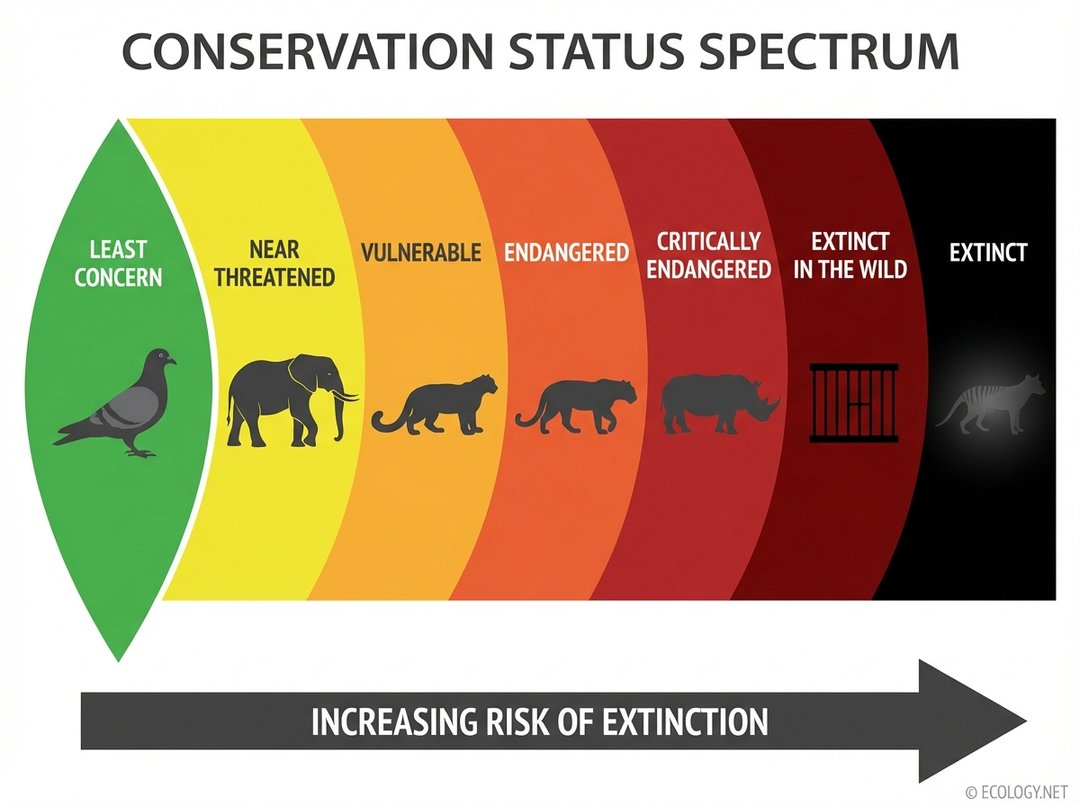

What Does “Threatened” Really Mean? Decoding the IUCN Red List

When scientists and conservationists speak of threatened species, they often refer to the categories established by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, or IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biological species. It uses a rigorous set of criteria to evaluate the extinction risk of thousands of species and subspecies.

The Red List categorizes species along a spectrum of risk, moving from those with healthy populations to those that have vanished forever. Here is a breakdown of the key categories:

- Least Concern (LC): These species are widespread and abundant, like the common pigeon or the human species. Their populations are stable, and they face no immediate threat of extinction.

- Near Threatened (NT): Species in this category are close to qualifying for a threatened category, or are likely to qualify in the near future. The African elephant, for example, faces significant poaching pressures and habitat loss, placing it in this precarious position.

- Vulnerable (VU): These species face a high risk of extinction in the wild. The polar bear, grappling with melting sea ice due to climate change, is a stark example.

- Endangered (EN): Species classified as Endangered face a very high risk of extinction in the wild. The snow leopard, with its fragmented mountain habitat and declining prey, exemplifies this critical status.

- Critically Endangered (CR): This is the highest risk category for species still existing in the wild. Critically Endangered species face an extremely high risk of extinction. The Amur leopard, with only dozens remaining in the wild, is a poignant symbol of this extreme vulnerability.

- Extinct in the Wild (EW): These species survive only in captivity or as naturalized populations outside their historic range. The scimitar oryx, once native to North Africa, now exists only in zoos and protected reserves.

- Extinct (EX): This category is reserved for species for which there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. The Tasmanian tiger, last seen in the 1930s, serves as a somber reminder of irreversible loss.

The term “threatened species” typically refers to those categorized as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered. These are the species that demand urgent conservation attention to prevent their slide towards extinction.

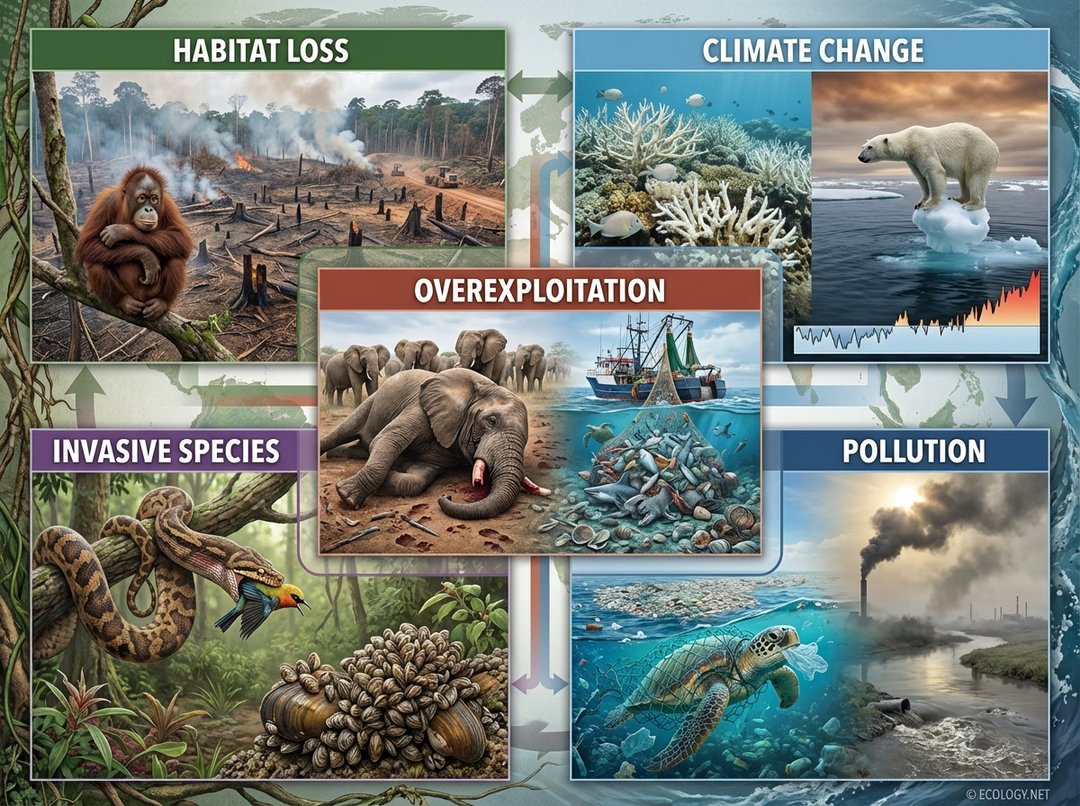

Why Are Species Threatened? The Major Drivers of Decline

The reasons behind species decline are complex and often interconnected, forming a web of challenges that push populations towards the brink. Scientists have identified five primary drivers of species threat, each exerting immense pressure on biodiversity.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

The single greatest threat to biodiversity is the destruction and degradation of natural habitats. As human populations expand, forests are cleared for agriculture, wetlands are drained for development, and grasslands are converted into urban areas. This not only reduces the total amount of available habitat but also breaks up remaining habitats into smaller, isolated patches. This process, known as habitat fragmentation, creates “islands” of habitat surrounded by human-dominated landscapes, making it difficult for species to find food, mates, and escape predators. For instance, the orangutan in Borneo and Sumatra faces severe threats as its rainforest home is cleared for palm oil plantations.

Climate Change

A rapidly changing global climate is altering ecosystems faster than many species can adapt. Rising global temperatures lead to melting glaciers and sea ice, impacting species like polar bears and seals. Changes in precipitation patterns cause droughts or floods, affecting plant growth and water availability for animals. Ocean acidification, a direct consequence of increased carbon dioxide absorption by the oceans, threatens marine life, particularly coral reefs and shellfish. Many species, such as the pika in North America, are being forced to higher altitudes to escape warming temperatures, running out of suitable habitat.

Overexploitation

This driver refers to the unsustainable harvesting of plants and animals, often for human consumption or trade. Overfishing has depleted fish stocks in oceans worldwide, impacting marine ecosystems and the livelihoods of fishing communities. Illegal wildlife trade, or poaching, targets iconic species like elephants for their ivory, rhinos for their horns, and pangolins for their scales, pushing them towards extinction. The vaquita, a small porpoise found only in the Gulf of California, is critically endangered primarily due to entanglement in illegal gillnets set for other species.

Invasive Species

When non-native species are introduced to new environments, either intentionally or accidentally, they can outcompete native species for resources, prey upon them, or introduce diseases. These invaders often lack natural predators in their new homes, allowing their populations to explode and wreak havoc on local ecosystems. The brown tree snake, introduced to Guam, decimated native bird populations, leading to the extinction of several species. Zebra mussels, introduced to the Great Lakes, have outcompeted native mussels and clogged water infrastructure.

Pollution

The introduction of harmful substances into the environment poses a significant threat to species. Plastic pollution chokes marine animals and contaminates food chains. Chemical pesticides and herbicides can poison insects, birds, and mammals. Industrial pollutants contaminate air and water, leading to respiratory problems, reproductive failures, and widespread ecosystem damage. Oil spills, though often localized, can have devastating immediate and long-term impacts on marine life and coastal habitats. Sea turtles, for example, frequently mistake plastic bags for jellyfish, leading to fatal ingestion.

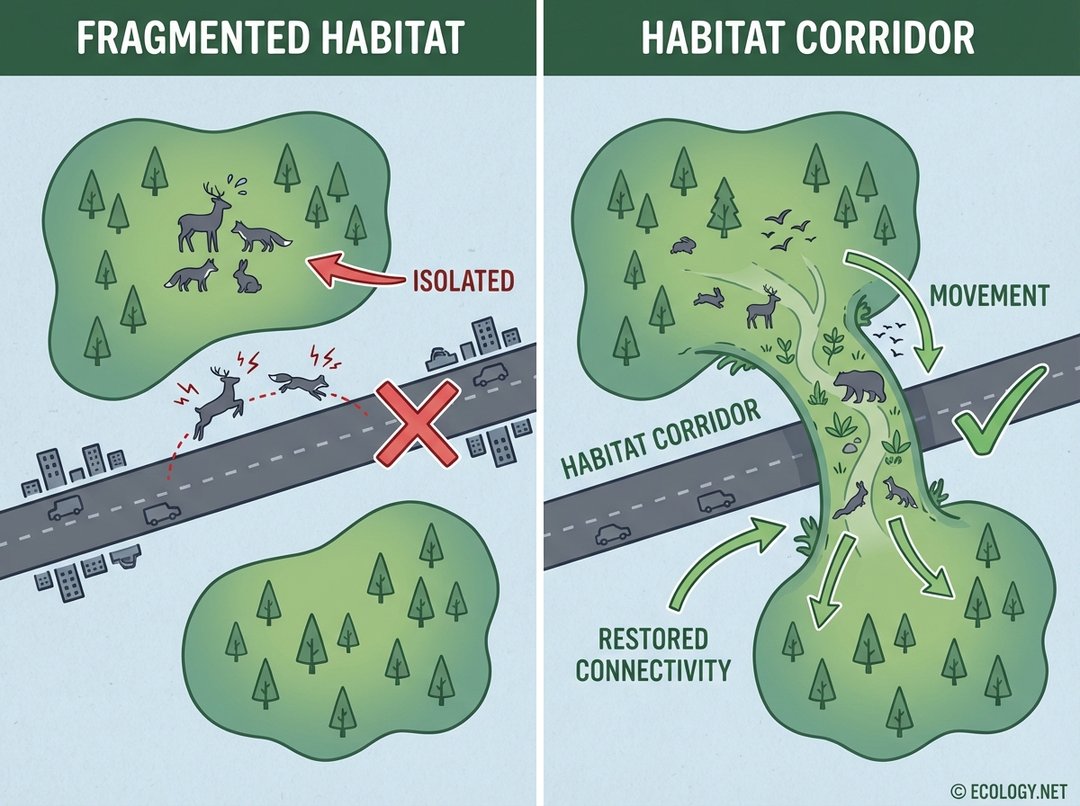

A Closer Look at Habitat Loss: Fragmentation and the Power of Corridors

Habitat loss is not always a complete disappearance of an ecosystem. Often, it involves the breaking apart of large, continuous habitats into smaller, isolated fragments. Imagine a vast forest being bisected by a new highway or a growing town. This fragmentation has profound consequences for wildlife.

When habitats are fragmented, animal populations become isolated. This isolation can lead to:

- Reduced genetic diversity: Small, isolated populations are more prone to inbreeding, which weakens their ability to adapt to environmental changes and fight off diseases.

- Limited access to resources: Animals may struggle to find enough food, water, or suitable mates if their movement is restricted to a small patch.

- Increased predation risk: Animals attempting to cross human-dominated landscapes between fragments are often vulnerable to traffic accidents or encounters with domestic animals.

- Edge effects: The boundaries between natural habitats and human-modified areas experience different environmental conditions, such as increased light, wind, and invasive species, which can degrade the quality of the remaining habitat.

One powerful solution to combat habitat fragmentation is the creation of habitat corridors. These are strips of natural habitat that connect otherwise isolated patches, allowing wildlife to move safely between them. Corridors can take many forms, from forested strips along rivers to specially designed wildlife bridges over highways. By restoring connectivity, habitat corridors help to:

- Increase genetic exchange between populations, boosting their resilience.

- Provide access to a wider range of resources, improving survival rates.

- Allow species to adapt to climate change by moving to more suitable areas.

- Reduce human-wildlife conflict by providing safe passage.

Examples of successful corridor projects include wildlife crossings in Banff National Park, Canada, which allow bears, elk, and other large mammals to safely traverse busy highways, and efforts to connect fragmented forest patches for jaguars in Central and South America.

The Ripple Effect: Why Should We Care About Threatened Species?

The loss of a single species might seem insignificant in the grand scheme of things, but the reality is far more profound. Every species plays a role, and their decline can trigger a cascade of negative effects throughout an ecosystem and beyond.

Ecological Importance

Biodiversity is the foundation of healthy ecosystems. Species contribute to vital ecosystem services that directly benefit humans:

- Pollination: Insects, birds, and bats pollinate crops and wild plants, essential for food production and ecosystem health.

- Pest control: Predators like birds and bats help control insect populations, reducing the need for harmful pesticides.

- Water purification: Wetlands and forests filter water, providing clean drinking water.

- Soil fertility: Decomposers and soil organisms enrich soil, supporting plant growth.

- Climate regulation: Forests absorb carbon dioxide, helping to mitigate climate change.

When species are lost, these services can degrade, leading to less productive land, poorer water quality, and increased vulnerability to environmental changes. The loss of a keystone species, like a top predator such as a wolf or a sea otter, can dramatically alter an entire food web, leading to unforeseen consequences.

Economic and Cultural Value

Biodiversity also holds immense economic and cultural value. Many medicines are derived from plants and animals. Ecotourism, which relies on healthy ecosystems and diverse wildlife, generates significant revenue for many communities. Indigenous cultures often have deep spiritual and practical connections to specific species and their habitats, and the loss of these species represents a loss of cultural heritage.

Ethical and Aesthetic Considerations

Beyond their practical value, many believe that all species have an intrinsic right to exist. There is also an aesthetic and spiritual value in the diversity of life on Earth. The wonder of seeing a majestic tiger in the wild or the intricate beauty of a coral reef enriches human experience. Losing these natural treasures diminishes the world for future generations.

Conservation in Action: What’s Being Done to Protect Species?

Despite the daunting challenges, dedicated conservation efforts worldwide are making a difference. A multi-faceted approach is essential, involving scientific research, policy changes, and community engagement.

Protected Areas and Habitat Restoration

Establishing national parks, wildlife reserves, and marine protected areas safeguards critical habitats and provides refuges for threatened species. Beyond protection, active habitat restoration projects, such as reforestation, wetland creation, and invasive species removal, are vital for repairing damaged ecosystems.

Species-Specific Recovery Plans

For critically endangered species, targeted recovery plans are often implemented. These can include:

- Captive breeding programs: Breeding animals in zoos or specialized facilities to increase their numbers, such as with the California condor.

- Reintroduction programs: Releasing captive-bred or translocated wild individuals back into their historical ranges, as seen with the black-footed ferret.

- Anti-poaching efforts: Increased patrols, community involvement, and technological surveillance to combat illegal wildlife trade.

International Agreements and Policy

Global cooperation is crucial for addressing transboundary threats. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) regulates the international trade of wild animals and plants, ensuring it does not threaten their survival. Other agreements focus on migratory species or specific ecosystems.

Community Involvement and Education

Engaging local communities in conservation efforts is paramount. When local people benefit from conservation, they become powerful allies. Education programs raise awareness about the importance of biodiversity and empower individuals to make conservation-minded choices.

Technological Advancements

New technologies are revolutionizing conservation. DNA analysis helps track illegal wildlife products. Satellite imagery monitors deforestation and habitat change. Drones assist in anti-poaching efforts and wildlife surveys. Artificial intelligence is being used to analyze vast datasets to predict and mitigate threats.

What Can You Do? Practical Steps for Everyone

Protecting threatened species is a collective responsibility. While large-scale efforts are vital, individual actions can also contribute significantly to conservation.

- Support Conservation Organizations: Donate to or volunteer with reputable organizations working on the front lines of conservation.

- Reduce Your Ecological Footprint: Make conscious choices to conserve energy, reduce waste, and minimize your consumption. Opt for public transport, bike, or walk when possible.

- Make Informed Consumer Choices: Choose sustainably sourced products. Look for certifications that indicate responsible forestry (e.g., FSC) or sustainable seafood (e.g., MSC). Avoid products made from endangered species or their parts.

- Educate Yourself and Others: Learn about local and global conservation issues. Share your knowledge with friends, family, and your community.

- Participate in Citizen Science: Join programs that involve public participation in scientific research, such as bird counts or monitoring local wildlife. Your observations can contribute valuable data to conservation efforts.

- Advocate for Policy Change: Contact your elected officials to express your support for strong environmental policies and funding for conservation initiatives.

- Support Local and Sustainable Agriculture: Choose locally grown produce and support farmers who use sustainable practices, reducing habitat destruction and chemical runoff.

A Future for All Species

The plight of threatened species is a powerful indicator of the health of our planet. Their decline signals imbalances in ecosystems that ultimately affect all life, including our own. By understanding the threats they face, appreciating their ecological importance, and actively participating in conservation, humanity can shift the trajectory from loss to recovery. The future of Earth’s incredible biodiversity, and indeed our own, depends on the choices we make today.