Unveiling the World of Habitats: Where Life Thrives

Every living creature, from the smallest microbe to the largest whale, calls a specific place home. This home, far more than just a location, is a dynamic tapestry of conditions and interactions known as a habitat. Understanding habitats is fundamental to comprehending life on Earth, revealing how organisms survive, reproduce, and contribute to the intricate web of ecosystems.

What Exactly is a Habitat?

At its core, a habitat is the natural environment where an organism or a population of organisms lives. It provides everything an organism needs to survive: food, water, shelter, and space to reproduce. Think of it as a life support system tailored to the specific needs of its inhabitants.

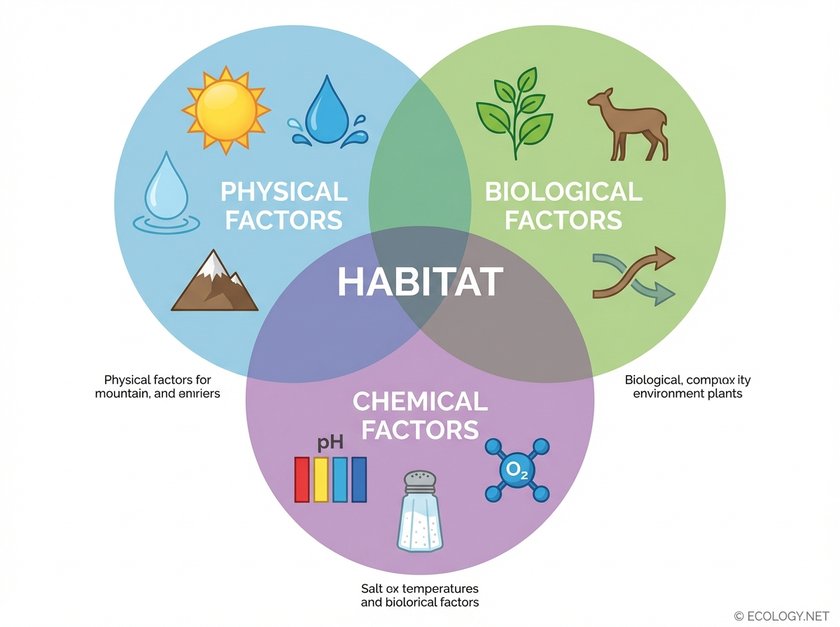

A habitat is not merely a geographical spot; it is a complex interplay of various elements. Ecologists categorize these elements into three main groups:

- Physical Factors: These are the non-living components of the environment. They include elements like temperature, sunlight, soil type, water availability, and geographical features such as mountains or valleys. A desert cactus, for instance, thrives in a habitat defined by high temperatures and minimal water.

- Biological Factors: These encompass all the living organisms within a habitat, including plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. These living components interact in countless ways: predator and prey relationships, competition for resources, symbiotic partnerships, and decomposition. The presence of specific plants might provide food and shelter for certain animals, shaping the biological landscape.

- Chemical Factors: These are the chemical properties of the habitat’s air, water, and soil. Key chemical factors include pH levels, salinity, oxygen concentration, and nutrient availability. For example, the pH of soil dictates which plants can grow, which in turn affects the animals that feed on those plants.

It is the unique combination and interaction of these physical, biological, and chemical factors that define a particular habitat and determine which species can successfully inhabit it.

A Closer Look: The Pond as a Habitat Example

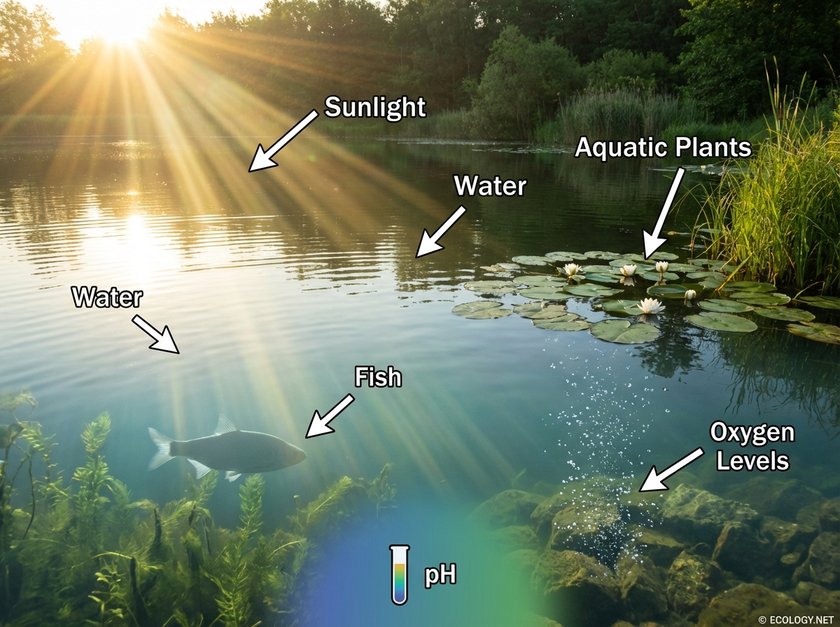

To make these concepts more tangible, consider a common freshwater pond. This seemingly simple body of water is a bustling habitat supporting a diverse array of life:

- Physical Factors:

- Sunlight: Penetrates the water, fueling photosynthesis in aquatic plants.

- Water Temperature: Varies with depth and season, influencing metabolic rates of cold-blooded organisms.

- Depth and Sediment: Affect light penetration and provide substrate for rooted plants and burrowing invertebrates.

- Biological Factors:

- Aquatic Plants: Lily pads, reeds, and algae provide food, oxygen, and shelter.

- Fish: Such as bass or minnows, act as predators and prey.

- Insects: Dragonflies, water striders, and their larvae contribute to the food web.

- Microorganisms: Bacteria and fungi decompose organic matter, recycling nutrients.

- Chemical Factors:

- Oxygen Levels: Crucial for fish and other aquatic animals, produced by plants.

- pH: The acidity or alkalinity of the water affects the survival of many species.

- Nutrient Levels: Nitrates and phosphates from runoff can influence algal growth.

All these elements interact dynamically. Sunlight drives plant growth, which produces oxygen and food for fish. Fish waste contributes nutrients, which are then processed by bacteria. A change in one factor, such as a sudden drop in oxygen, can have cascading effects throughout the entire pond habitat.

The Importance of Habitats

Habitats are the foundation of biodiversity. They are essential for:

- Species Survival: Providing the specific conditions and resources necessary for individual organisms to live and thrive.

- Reproduction: Offering safe places for mating, nesting, and raising young.

- Ecosystem Services: Healthy habitats contribute to vital processes like water purification, climate regulation, pollination, and nutrient cycling, all of which benefit human societies.

- Genetic Diversity: Supporting a wide range of species, which in turn maintains genetic diversity within and between populations, enhancing resilience to environmental changes.

Beyond the Obvious: Exploring Different Habitat Types

Habitats are incredibly diverse, ranging from vast oceans to tiny cracks in rocks. They can be broadly categorized:

- Terrestrial Habitats: Found on land, including forests, grasslands, deserts, mountains, and tundras. Each has distinct physical and biological characteristics.

- Aquatic Habitats: Found in water, encompassing freshwater environments like rivers, lakes, and ponds, as well as marine environments like oceans, coral reefs, and estuaries.

- Arboreal Habitats: Specifically refer to habitats found in trees, crucial for many bird, insect, and primate species.

- Subterranean Habitats: Found underground, such as caves, burrows, and soil layers, home to unique organisms adapted to darkness and stable conditions.

Within these broad categories, even smaller, specialized environments exist. A “microhabitat” is a small, localized area within a larger habitat that has distinct environmental conditions. For example, a single rotting log in a forest is a microhabitat for beetles, fungi, and mosses, offering different conditions than the surrounding forest floor.

Threats to Habitats: A Global Challenge

Despite their critical importance, habitats worldwide face unprecedented threats, primarily due to human activities. These threats lead to habitat degradation, loss, and fragmentation, with severe consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem health.

- Habitat Loss: This is the complete destruction of a habitat, often for agriculture, urbanization, or resource extraction. When a forest is cleared for a housing development, the entire habitat is lost, displacing or eliminating all species that lived there.

- Habitat Degradation: This involves the reduction in the quality of a habitat, making it less suitable for its inhabitants. Pollution, for example, can contaminate water sources, making a pond habitat toxic for fish and insects.

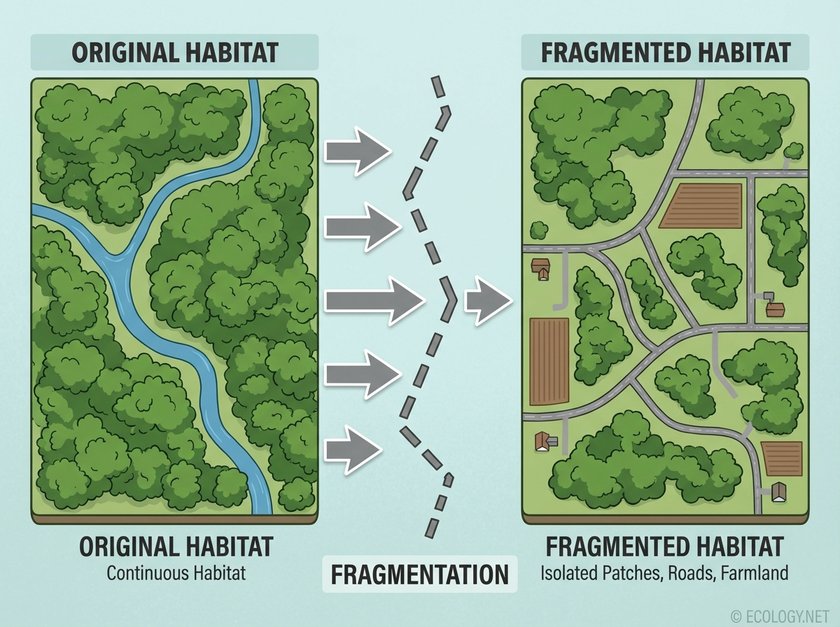

- Habitat Fragmentation: This occurs when a large, continuous habitat is broken into smaller, isolated patches. Roads, agricultural fields, and urban development often cause fragmentation. This process isolates populations, reduces genetic exchange, and makes species more vulnerable to local extinction. Small patches may not provide enough resources or space for larger animals, and the “edge effect” where fragmented areas meet human-modified landscapes can negatively impact interior species.

Other significant threats include climate change, which alters temperature and precipitation patterns, shifting habitat suitability; invasive species, which outcompete native organisms; and overexploitation of resources, which depletes populations and disrupts ecological balances.

Protecting Our Planet’s Homes: Conservation and Restoration

Recognizing the profound impact of habitat loss, conservation efforts are crucial. These efforts include:

- Establishing Protected Areas: National parks, wildlife refuges, and marine protected areas safeguard critical habitats from human disturbance.

- Sustainable Land Use: Implementing practices that minimize environmental impact, such as sustainable forestry and agriculture.

- Habitat Restoration: Actively repairing degraded or destroyed habitats, for example, by reforesting cleared land or cleaning polluted waterways.

- Corridor Creation: Building wildlife corridors, such as underpasses or overpasses, to connect fragmented habitats, allowing species to move safely between patches.

Understanding the concept of a habitat is the first step toward appreciating the complexity of life on Earth and recognizing our role in its preservation. Every action, from supporting conservation initiatives to making conscious daily choices, contributes to the health of these vital natural homes.

Conclusion

A habitat is more than just a place; it is a dynamic, interconnected system where physical, biological, and chemical factors converge to support life. From the vastness of the ocean to the intimacy of a rotting log, each habitat is a unique stage for the drama of survival and evolution. By understanding, valuing, and protecting these essential environments, humanity ensures not only the survival of countless species but also the health and resilience of our own planet.