The natural world is a tapestry woven with countless species, each playing a unique role in the intricate dance of life. Yet, this vibrant tapestry is fraying at an alarming rate, with many threads teetering on the brink of disappearance. The term “endangered species” has become a stark reminder of the profound impact human activities have on our planet’s biodiversity. Understanding what an endangered species is, why they become endangered, and what their loss means for all of us is crucial for safeguarding the future of life on Earth.

Understanding the Levels of Conservation Concern

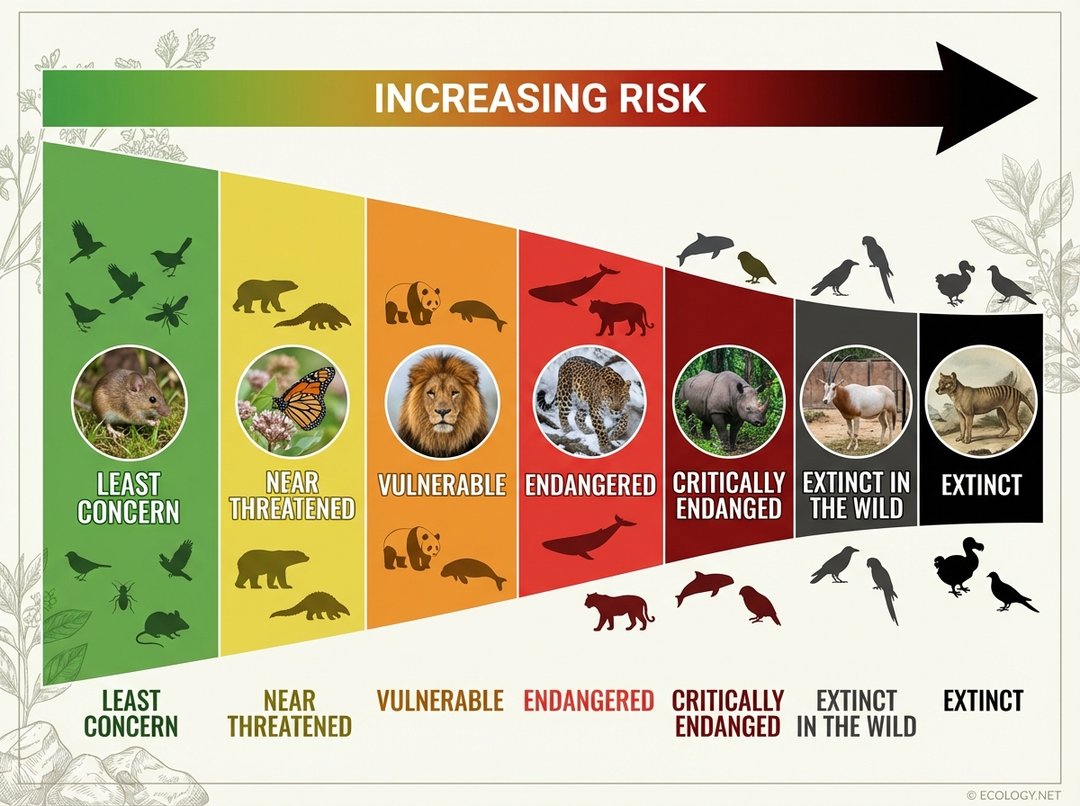

When scientists and conservationists talk about species at risk, they rely on a globally recognized system: the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This comprehensive inventory, maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, assesses the conservation status of species worldwide. It provides a clear framework for categorizing species based on their risk of extinction, moving from relatively safe to critically imperiled.

The Red List categorizes species into several groups, each signifying a different level of threat:

- Least Concern (LC): Species with a widespread and abundant population, such as the common mouse.

- Near Threatened (NT): Species that are close to qualifying for a threatened category, or are likely to qualify in the near future.

- Vulnerable (VU): Species facing a high risk of extinction in the wild, like the African lion, due to declining populations or restricted ranges.

- Endangered (EN): Species facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild. The Amur leopard, with its critically small population, is a poignant example.

- Critically Endangered (CR): Species facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild. The Javan rhino, with only a handful of individuals remaining, exemplifies this dire situation.

- Extinct in the Wild (EW): Species known only to survive in captivity or as naturalized populations outside their historic range.

- Extinct (EX): Species for which there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. The Tasmanian tiger, last seen in the 1930s, serves as a tragic reminder of permanent loss.

These categories are not static; a species’ status can improve with successful conservation efforts or worsen if threats intensify. The Red List acts as a vital barometer for global biodiversity, guiding conservation priorities and actions.

What Drives Species Towards Endangerment?

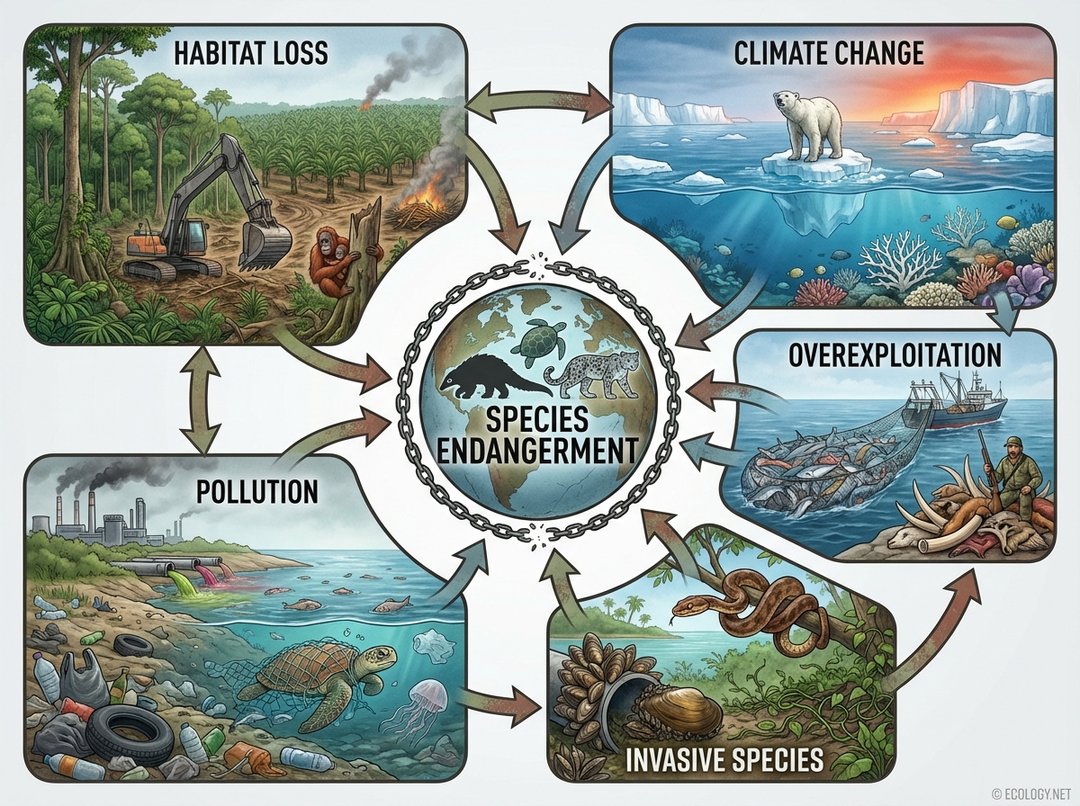

The path to endangerment is rarely simple, often involving a complex interplay of factors that erode a species’ ability to survive and reproduce. While natural processes like disease or geological events can contribute, the overwhelming majority of current extinctions are driven by human activities. Understanding these primary threats is the first step towards mitigating them.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

This is arguably the single greatest threat to biodiversity. As human populations expand, natural landscapes are converted for agriculture, urban development, infrastructure, and resource extraction. Forests are cleared for palm oil plantations, wetlands are drained for housing, and grasslands are plowed for crops. This destruction directly removes the places where species live, feed, and breed. Even when habitats are not completely destroyed, they can become fragmented, making it difficult for animals to find mates, food, or escape predators, leading to isolated and vulnerable populations.

Climate Change

The warming of our planet is altering ecosystems at an unprecedented pace. Rising global temperatures lead to changes in weather patterns, sea levels, and ocean acidity. Species adapted to specific climatic conditions struggle to cope. For instance, polar bears face starvation as melting Arctic sea ice reduces their hunting grounds. Coral reefs, vital marine ecosystems, suffer from bleaching events caused by warmer ocean temperatures. Many species cannot adapt or migrate quickly enough to keep pace with these rapid environmental shifts.

Overexploitation

When humans harvest species from the wild at rates faster than they can replenish, it leads to overexploitation. This can take many forms: unsustainable fishing practices that deplete fish stocks, illegal wildlife trade for exotic pets or traditional medicine, and excessive hunting. The passenger pigeon, once one of the most abundant birds in North America, was hunted to extinction in the early 20th century, a stark example of how even seemingly limitless populations can be decimated by unchecked exploitation.

Invasive Species

When non-native species are introduced into an ecosystem, either intentionally or accidentally, they can wreak havoc on native flora and fauna. Without natural predators or competitors, invasive species can outcompete native species for resources, prey upon them, or introduce diseases. The brown tree snake, introduced to Guam, decimated the island’s native bird populations. Zebra mussels, transported via ship ballast water, have altered freshwater ecosystems across North America, outcompeting native mussels and clogging infrastructure.

Pollution

The release of harmful substances into the environment poses a significant threat to many species. Plastic waste chokes marine animals and birds, pesticides contaminate food chains, and industrial chemicals poison water sources. Air pollution can degrade habitats and directly harm respiratory systems. For example, plastic pollution in oceans is a major concern, with countless marine animals ingesting plastic debris or becoming entangled in it, leading to injury or death.

Why Does it Matter? The Ecological Ripple Effect

The loss of a single species is not an isolated event; it sends ripples through an entire ecosystem. Biodiversity, the variety of life on Earth, is fundamental to the health and stability of our planet. Each species contributes to a complex web of interactions, performing vital roles that collectively support life, including human life.

- Ecosystem Services: Healthy ecosystems provide invaluable “services” that we often take for granted. These include clean air and water, pollination of crops, regulation of climate, soil formation, and nutrient cycling. The loss of species can impair these services, leading to consequences like reduced agricultural yields, increased natural disasters, and diminished water quality.

- Genetic Diversity: Each species represents a unique collection of genetic material. This genetic diversity is the raw material for adaptation and evolution. Losing a species means losing a unique genetic library, potentially depriving future generations of solutions to environmental challenges, new medicines, or resilient food sources.

- Interconnectedness: Ecosystems are intricate networks where species depend on each other for survival. The disappearance of one species can trigger a cascade of effects, impacting predators, prey, and even the physical environment.

Keystone Species and Trophic Cascades

Some species play a disproportionately large role in maintaining the structure and function of an ecosystem. These are known as keystone species. Their removal can lead to dramatic changes, often far greater than their abundance might suggest. The concept of a trophic cascade illustrates this phenomenon, showing how impacts at one trophic (feeding) level can ripple through an entire food web.

A classic example of a keystone species and a trophic cascade involves the sea otter in kelp forest ecosystems along the Pacific coast. Consider these two scenarios:

- Sea Otter Present (Healthy Ecosystem): In a vibrant kelp forest, sea otters feed on sea urchins. By keeping urchin populations in check, the otters prevent them from overgrazing the kelp. This allows the kelp forests to thrive, providing habitat and food for a multitude of other marine species, from fish to invertebrates. The ecosystem is rich and diverse.

- Sea Otter Absent (Degraded Ecosystem): When sea otter populations decline due to hunting or disease, their primary prey, sea urchins, multiply unchecked. These abundant urchins consume vast quantities of kelp, turning lush kelp forests into barren “urchin barrens.” This loss of kelp habitat devastates the entire ecosystem, leading to declines in fish populations, marine invertebrates, and other species that rely on the kelp for shelter and food. The entire food web collapses in the absence of this single keystone predator.

Other examples of keystone species include wolves in Yellowstone National Park, whose reintroduction helped restore riparian ecosystems by controlling elk populations, and elephants in African savannas, which shape landscapes by felling trees and creating waterholes. The loss of such species can fundamentally alter the very fabric of an ecosystem, sometimes irreversibly.

Conservation in Action: Hope and Solutions

Despite the daunting challenges, there is significant hope for endangered species. Conservation efforts around the globe are making a tangible difference. These efforts often involve a multi-faceted approach:

- Habitat Protection and Restoration: Establishing protected areas, national parks, and wildlife reserves safeguards critical habitats. Restoration projects aim to repair degraded ecosystems, replanting forests, cleaning rivers, and re-establishing wetlands.

- Species-Specific Interventions: This includes captive breeding programs to boost populations of critically endangered species, reintroduction programs to release animals back into the wild, and anti-poaching initiatives to combat illegal wildlife trade.

- Policy and Legislation: International agreements like CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) and national laws protect endangered species and regulate activities that might harm them.

- Community Engagement: Working with local communities is vital for long-term success. Empowering people to become stewards of their local environment, providing sustainable livelihoods, and educating about the value of biodiversity fosters a shared commitment to conservation.

- Scientific Research: Understanding species’ biology, ecological roles, and the threats they face is crucial for developing effective conservation strategies.

A Call to Action for a Thriving Planet

The plight of endangered species is a powerful indicator of the health of our planet. Their decline signals imbalances in ecosystems that ultimately affect all life, including our own. By understanding the intricate web of life, the threats that imperil it, and the profound impact of species loss, we can move towards a future where biodiversity thrives.

Every individual action, from supporting sustainable practices and responsible consumption to advocating for conservation policies and educating others, contributes to the larger effort. Protecting endangered species is not just about saving individual animals; it is about preserving the rich tapestry of life that sustains us all, ensuring a healthy and vibrant planet for generations to come.