Pesticides are a ubiquitous presence in modern society, often sparking intense debate and curiosity. From ensuring bountiful harvests to protecting public health, these chemical compounds play a significant role in human endeavors. Yet, their widespread application also raises critical questions about environmental integrity and long-term health implications. Understanding pesticides requires a journey into their diverse forms, their intricate interactions with ecosystems, and the innovative strategies emerging for more sustainable pest management.

What Exactly Are Pesticides?

At its core, a pesticide is any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling, or mitigating any pest. The term “pest” is broad, encompassing insects, weeds, fungi, rodents, and even microorganisms that are deemed detrimental to human interests, agriculture, or health. While often associated with synthetic chemicals, pesticides can also include biological agents, biopesticides, and naturally derived substances.

The world of pesticides is far from monolithic. These compounds are categorized based on the type of pest they target, each designed with specific mechanisms to achieve its goal.

Here are the primary categories:

- Insecticides: These are designed to control insects. They can work in various ways, such as disrupting the nervous system (e.g., organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, neonicotinoids), interfering with growth and development, or acting as stomach poisons. Examples include malathion for mosquito control or imidacloprid for crop protection.

- Herbicides: Targeting unwanted plants, or weeds, herbicides are crucial in agriculture for maximizing crop yields. They can be selective, killing only certain types of plants (e.g., 2,4-D for broadleaf weeds), or non-selective, killing almost all plant life (e.g., glyphosate).

- Fungicides: These substances are used to control fungal diseases that can devastate crops, ornamental plants, and even cause human illnesses. They prevent fungal growth or kill existing fungi, protecting plants from blight, rusts, and mildews.

- Rodenticides: Specifically formulated to kill rodents like rats and mice, which can be agricultural pests, disease vectors, and destroyers of property. Many rodenticides are anticoagulants, causing internal bleeding.

- Bactericides/Virucides: While less commonly discussed in the context of agricultural pest control, these agents target bacteria and viruses. Bactericides are used in various settings, from agriculture to healthcare, to prevent bacterial diseases. Virucides are designed to inactivate viruses.

The Double-Edged Sword: Benefits and Risks

The widespread adoption of pesticides stems from their undeniable benefits, particularly in the realm of food production and public health. However, these advantages come with significant environmental and health trade-offs.

The Benefits: A Shield Against Pests

Pesticides have been instrumental in:

- Increasing Agricultural Productivity: By protecting crops from insects, weeds, and diseases, pesticides significantly boost yields, ensuring a more stable and affordable food supply for a growing global population. For instance, without herbicides, manual weeding would be far more labor-intensive and less effective, leading to higher food costs and scarcity.

- Controlling Disease Vectors: Insecticides have been vital in controlling populations of disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes (malaria, dengue fever, Zika virus) and ticks (Lyme disease), thereby preventing widespread epidemics and saving countless lives.

- Protecting Infrastructure and Property: Rodenticides and insecticides protect homes, businesses, and infrastructure from damage caused by pests like termites, rats, and cockroaches.

The Risks: Unintended Consequences

Despite their utility, the application of pesticides is fraught with potential dangers:

- Environmental Contamination: Pesticides can leach into soil and groundwater, run off into rivers and lakes, and drift through the air, contaminating ecosystems far from their intended target.

- Impact on Non-Target Species: Many pesticides are not highly selective and can harm beneficial insects (like pollinators such as bees and butterflies), birds, fish, and other wildlife, disrupting ecological balance.

- Pest Resistance: Continuous use of the same pesticides can lead to the evolution of resistant pest populations, rendering the chemicals ineffective over time and necessitating the development of new, often stronger, compounds.

- Human Health Concerns: Exposure to pesticides, whether through direct contact, inhalation, or consumption of contaminated food and water, can lead to a range of health problems, from acute poisoning to chronic conditions.

How Pesticides Impact Ecosystems

The ecological footprint of pesticides extends far beyond the immediate area of application. Their persistence in the environment and their ability to move through food webs pose some of the most serious long-term threats.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: A Ticking Time Bomb

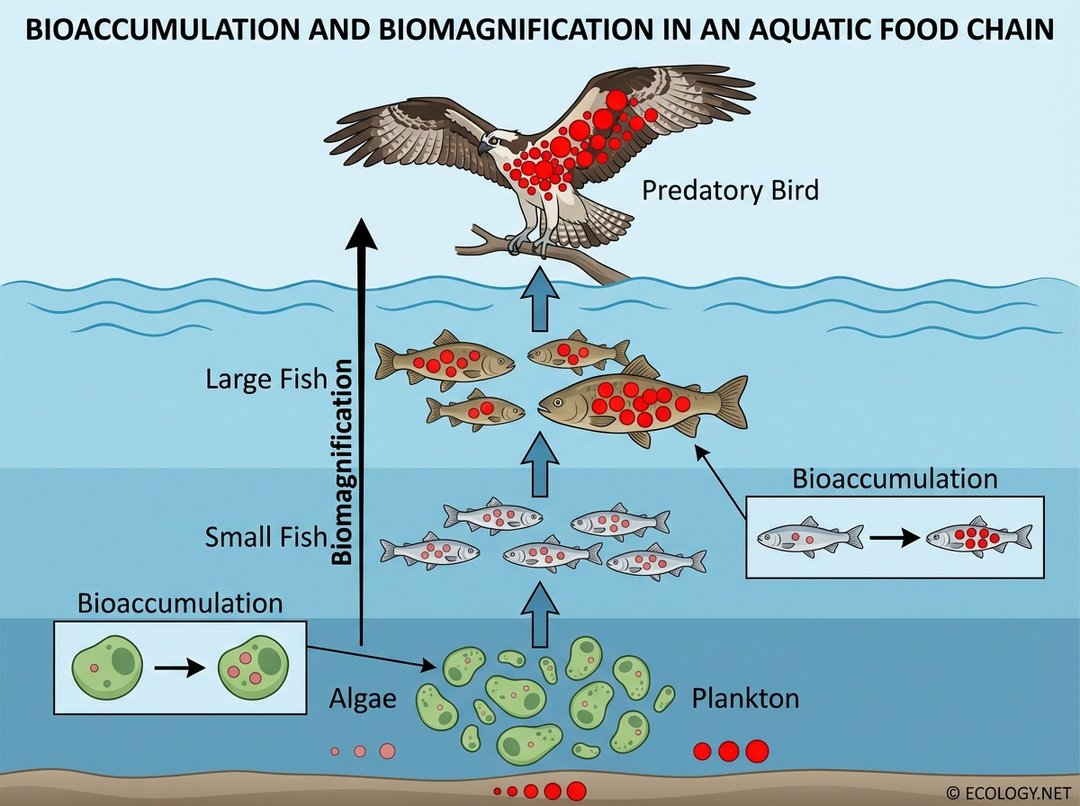

One of the most concerning ecological impacts of certain persistent pesticides is their ability to accumulate in living organisms and magnify up the food chain. This process involves two key phenomena:

- Bioaccumulation: This refers to the gradual build-up of a substance, such as a pesticide, in an organism’s tissues over time. If an organism is exposed to a pesticide faster than it can excrete or metabolize it, the concentration within its body will increase.

- Biomagnification: This is the increase in concentration of a pesticide in organisms at successively higher trophic levels in a food chain. As predatory animals consume multiple prey items, they ingest the accumulated pesticides from each prey, leading to significantly higher concentrations in top predators.

A classic example of biomagnification involved the insecticide DDT. After its widespread use in the mid-20th century, DDT accumulated in aquatic environments. Microscopic algae absorbed it, then small invertebrates ate the algae, small fish ate the invertebrates, larger fish ate the small fish, and finally, predatory birds like eagles and ospreys consumed the larger fish. At each step, the concentration of DDT increased, leading to severe reproductive issues in top predators, such as thin eggshells that broke during incubation, pushing many species to the brink of extinction. While DDT is now banned in many countries, other persistent organic pollutants (POPs) can exhibit similar behaviors.

Impact on Biodiversity

Beyond specific food chain effects, pesticides can broadly reduce biodiversity:

- Pollinator Decline: Neonicotinoid insecticides, for example, have been implicated in the decline of bee populations, which are crucial for pollinating a vast array of crops and wild plants.

- Soil Health Degradation: Pesticides can harm beneficial soil microorganisms, which are essential for nutrient cycling, soil structure, and overall soil fertility.

- Aquatic Ecosystem Damage: Runoff containing pesticides can be toxic to fish, amphibians, and aquatic invertebrates, disrupting entire freshwater and marine ecosystems.

Pesticides and Human Health

Human exposure to pesticides can occur through various pathways, including dietary intake, occupational exposure (e.g., farmers, pesticide applicators), and residential exposure (e.g., lawn care, household pest control). The health effects depend on the type of pesticide, the dose, the duration of exposure, and individual susceptibility.

Acute vs. Chronic Effects

- Acute Effects: These are immediate or short-term health problems that occur shortly after a single, high-level exposure. Symptoms can range from skin rashes, eye irritation, nausea, dizziness, and headaches to more severe issues like respiratory distress, seizures, and even death in cases of severe poisoning.

- Chronic Effects: These are long-term health problems that may develop months or years after repeated or prolonged exposure to lower levels of pesticides. Chronic effects are often more insidious and harder to link directly to pesticide exposure. Potential chronic effects include:

- Neurological disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, cognitive impairment)

- Reproductive problems (e.g., infertility, birth defects)

- Endocrine disruption (interfering with hormone systems)

- Certain cancers (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma, leukemia)

- Developmental effects in children (e.g., developmental delays, behavioral issues)

Children, pregnant women, and individuals with compromised immune systems are often more vulnerable to the adverse effects of pesticide exposure due to their developing bodies and unique physiological sensitivities.

The Path to Sustainable Pest Management

Recognizing the complex challenges posed by conventional pesticide use, there has been a significant shift towards more sustainable and ecologically sound approaches to pest control. The cornerstone of this movement is Integrated Pest Management (IPM).

Integrated Pest Management (IPM): A Holistic Strategy

IPM is an ecosystem-based strategy that focuses on long-term prevention of pests or their damage through a combination of techniques. It aims to manage pests in a way that minimizes economic, health, and environmental risks. IPM is not about eliminating pesticides entirely, but rather using them judiciously and only when necessary, as a last resort.

The core principles of IPM include:

- Pest Monitoring and Identification: Regular scouting and accurate identification of pests are crucial. This helps determine if pest populations are reaching economically damaging levels and ensures the correct control method is chosen.

- Setting Action Thresholds: IPM emphasizes that not every pest requires immediate action. Action thresholds are points at which pest populations or environmental conditions indicate that pest control action is necessary to prevent unacceptable damage.

- Prevention: The first line of defense in IPM is prevention. This involves practices that make the environment less favorable for pests.

- Control: If prevention fails and thresholds are met, IPM employs a combination of control methods, prioritizing the least-toxic options first.

Components of IPM: A Multi-pronged Approach

- Cultural Practices: These involve modifying growing practices to reduce pest establishment, reproduction, and survival. Examples include:

- Crop rotation: Breaking pest life cycles by planting different crops in successive seasons.

- Resistant varieties: Planting crop varieties bred to be resistant to specific pests or diseases.

- Sanitation: Removing pest habitats and food sources.

- Optimizing planting times: Avoiding periods when pests are most active.

- Physical/Mechanical Controls: These methods physically remove or exclude pests. Examples include:

- Hand-picking weeds or insects.

- Using barriers or netting to exclude pests.

- Traps (e.g., sticky traps, pheromone traps) to monitor or capture pests.

- Tillage to disrupt pest habitats.

- Biological Control: This involves using natural enemies (predators, parasites, pathogens) to control pest populations. For instance, introducing ladybugs to control aphids, or using specific bacteria (like Bacillus thuringiensis) to target caterpillar pests.

- Judicious Pesticide Use: Chemical pesticides are used only when necessary, after other methods have been considered, and in the most targeted and least-toxic formulations possible. This includes using spot treatments instead of broad applications, choosing pesticides with low environmental persistence, and rotating different chemical classes to prevent resistance.

Beyond IPM: Other Sustainable Practices

Other approaches complement IPM in fostering sustainable pest management:

- Organic Farming: This system relies on ecological processes, biodiversity, and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of synthetic inputs like pesticides and fertilizers.

- Agroecology: A holistic approach that integrates ecological principles into agricultural practices, aiming to create sustainable food systems that are environmentally sound, socially just, and economically viable.

- Precision Agriculture: Using technology (GPS, sensors, drones) to apply pesticides only where and when needed, minimizing overall chemical use.

Navigating Pesticide Use: Regulations and Consumer Choices

Governments worldwide regulate the development, sale, and use of pesticides to mitigate risks. Agencies conduct rigorous testing and risk assessments before approving pesticides, setting maximum residue limits (MRLs) for food, and providing guidelines for safe application. These regulations aim to strike a balance between agricultural productivity and public safety.

For consumers, making informed choices can also contribute to more sustainable practices. Opting for organic produce, which is grown without synthetic pesticides, or purchasing from local farmers who employ IPM strategies, can support environmentally conscious agriculture. Washing all produce thoroughly, regardless of its origin, is also a simple yet effective step to reduce potential pesticide residues.

Conclusion

Pesticides represent a complex and often contentious aspect of modern life. While they have offered significant benefits in food security and disease control, their ecological and health impacts necessitate a careful and informed approach. The journey towards sustainable pest management, spearheaded by strategies like Integrated Pest Management, offers a promising path forward. By embracing a multi-faceted approach that prioritizes prevention, ecological balance, and judicious intervention, humanity can continue to manage pests effectively while safeguarding the health of both people and the planet for generations to come.