Freshwater ecosystems are vibrant, life-sustaining environments that cover only a small fraction of Earth’s surface, yet they play an outsized role in supporting biodiversity and human well-being. From the rushing currents of mighty rivers to the tranquil depths of ancient lakes, the verdant expanses of wetlands, and the hidden networks of groundwater, these systems are critical for countless species, including our own. Understanding these dynamic environments is not just an academic exercise, it is essential for safeguarding the planet’s most precious resource: water.

What Exactly Are Freshwater Ecosystems?

At its core, a freshwater ecosystem is any aquatic environment characterized by a low salt concentration, typically less than 0.05%. This distinguishes them from marine ecosystems, which are salty, and brackish ecosystems, which have an intermediate salinity. Freshwater is the lifeblood for terrestrial and aquatic organisms alike, providing drinking water, irrigation for agriculture, and habitats for an astonishing array of plants and animals.

These ecosystems are incredibly diverse, shaped by factors such as water flow, depth, temperature, and surrounding geology. They are broadly categorized based on whether their water is flowing or still:

- Lotic Systems: These are environments with flowing water, such as rivers, streams, and creeks. The constant movement of water influences everything from the types of organisms that can thrive there to the nutrient cycling processes.

- Lentic Systems: These are environments with standing or still water, including lakes, ponds, and reservoirs. Water depth, light penetration, and thermal stratification are key characteristics defining these habitats.

- Wetlands: Often considered transitional zones, wetlands like marshes, swamps, and bogs can have either flowing or still water, but are defined by saturated soils and emergent vegetation.

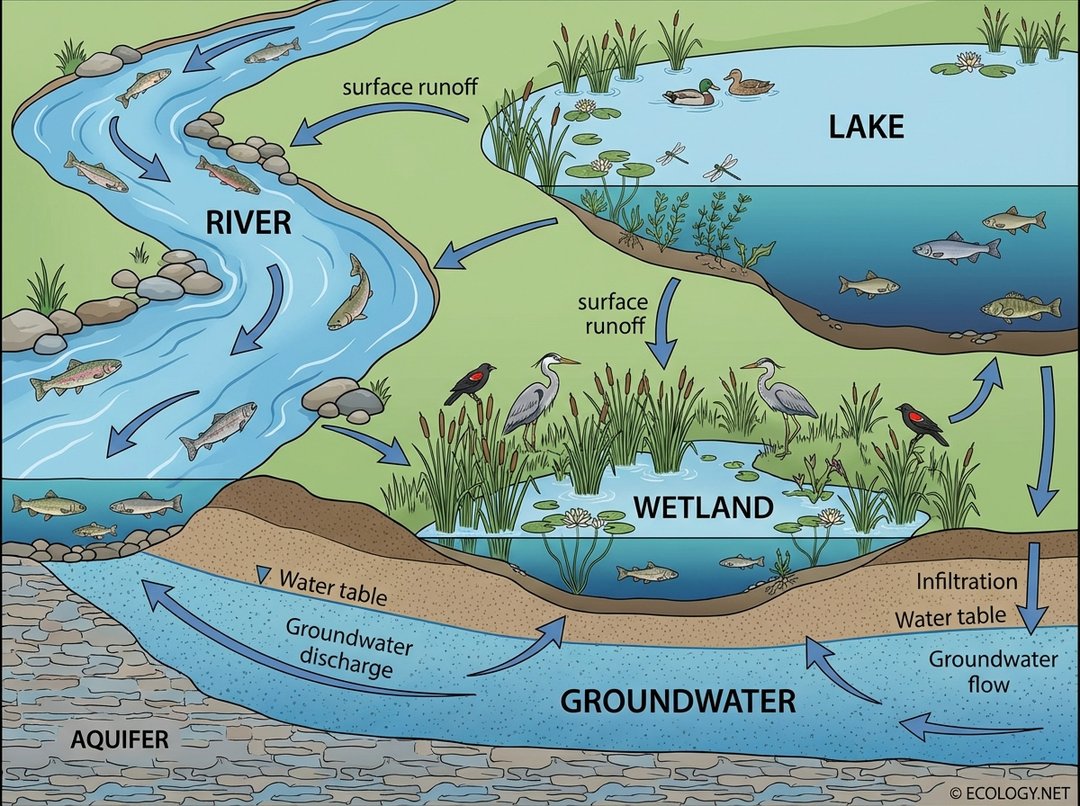

- Groundwater Systems: These are hidden networks of water found beneath the Earth’s surface in aquifers. Though often unseen, they are intrinsically linked to surface freshwater bodies.

Exploring Diverse Freshwater Habitats

The variety within freshwater ecosystems is truly remarkable, each type presenting unique challenges and opportunities for life. Let us delve into some of these distinct environments.

Rivers and Streams: The Veins of the Land

Rivers and streams are dynamic systems, constantly shaping the landscape as they flow from their headwaters to the sea or a larger body of water. The speed of the current, the substrate of the riverbed, and the surrounding vegetation all influence the types of life found within them. For instance, fast-flowing mountain streams might host organisms adapted to clinging to rocks, such as certain insect larvae or specialized fish like trout. Slower, wider rivers in flatter plains often support a greater diversity of fish, amphibians, and aquatic plants rooted in the softer sediments.

- Headwaters: Typically cold, clear, and oxygen-rich, with a narrow channel and fast flow. Life here is adapted to strong currents.

- Mid-reaches: Wider, warmer, and slower, with more sediment and nutrient input. Greater biodiversity often thrives here.

- Lower reaches: Broad, deep, and often turbid, with slow currents and fine sediments. These sections are often influenced by tidal forces or proximity to lakes.

Lakes and Ponds: Still Waters Run Deep

Lakes and ponds are bodies of standing water, varying immensely in size, depth, and origin. They can be glacial lakes carved by ice, tectonic lakes formed by Earth’s movements, or even artificial reservoirs created by dams. The stratification of water layers, particularly in deeper lakes, is a crucial factor. The warmer, sunlit surface layer (epilimnion) supports photosynthesis, while the colder, darker bottom layer (hypolimnion) can become oxygen-depleted, especially in productive lakes.

- Littoral Zone: The shallow, near-shore area where sunlight penetrates to the bottom, allowing rooted plants to grow. This zone is teeming with life.

- Limnetic Zone: The open water surface layer away from the shore, where phytoplankton and zooplankton thrive.

- Profundal Zone: The deep, dark bottom water where light does not penetrate, supporting organisms adapted to low oxygen and darkness.

Wetlands: Nature’s Sponges and Filters

Wetlands are areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including during the growing season. They are incredibly productive ecosystems, often referred to as “biological supermarkets” due to the vast food webs they support. Marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens are all types of wetlands, each with distinct vegetation and water chemistry. They act as natural filters, improving water quality, and as sponges, absorbing floodwaters and recharging groundwater.

Groundwater: The Hidden Reservoir

Beneath our feet lies a vast network of groundwater, stored in aquifers, which are permeable rock formations or sediments. This water is a critical source for many rivers, lakes, and wetlands, emerging as springs or seeping into surface bodies. Groundwater ecosystems, though less visible, host unique communities of organisms adapted to life without light, playing a vital role in nutrient cycling and water purification.

Life in Freshwater: The Web of Interconnections

The biodiversity within freshwater ecosystems is astounding, despite their relatively small global footprint. These environments are home to approximately 10% of all known species, including a third of all vertebrate species. Life here is intricately linked through complex food webs, where energy flows from producers to consumers and ultimately to decomposers.

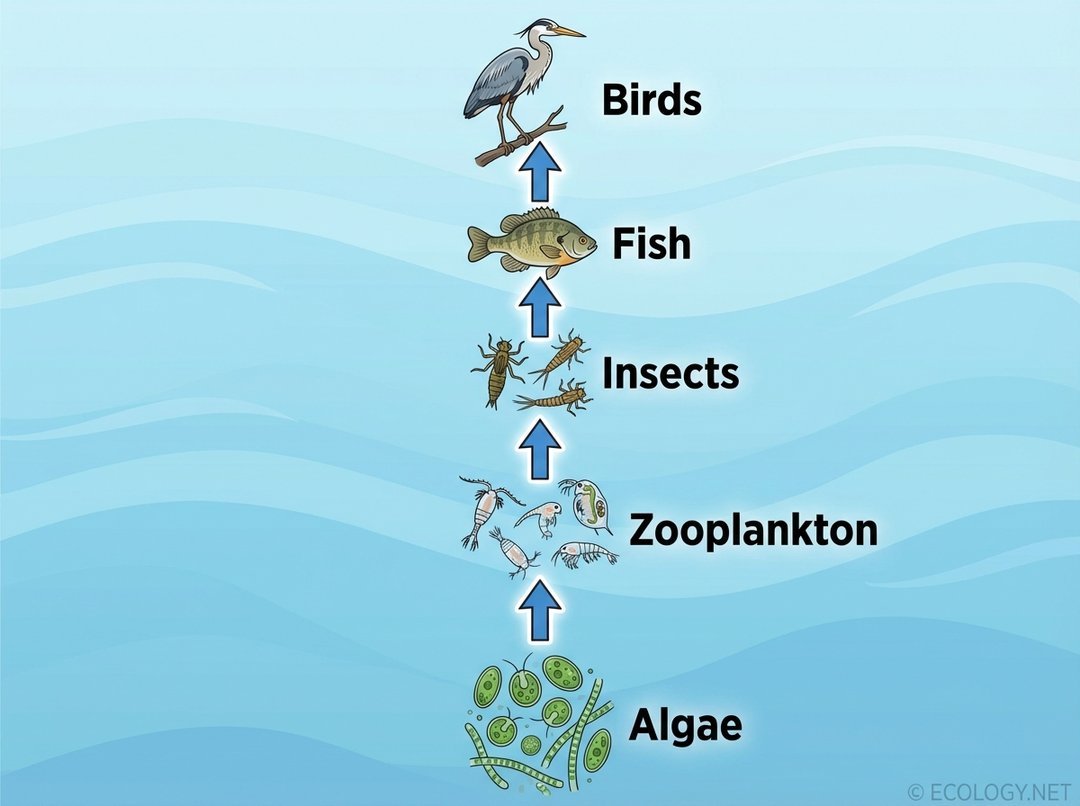

The Foundation: Producers

At the base of most freshwater food webs are the producers. These are organisms that create their own food, primarily through photosynthesis. In freshwater, this includes:

- Algae: Microscopic phytoplankton floating in the water column, and larger filamentous algae attached to surfaces.

- Aquatic Plants: Rooted plants like water lilies, cattails, and submerged grasses, especially prevalent in shallow zones of lakes and wetlands.

The Consumers: A Diverse Cast

Consumers obtain energy by eating other organisms. Freshwater ecosystems host a wide range of consumers:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These feed directly on producers. Examples include zooplankton (tiny crustaceans and rotifers that graze on phytoplankton), snails, and certain insect larvae.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores/Omnivores): These eat primary consumers. Many fish species, amphibians (like frogs and salamanders), and carnivorous insects fall into this category.

- Tertiary Consumers (Top Predators): These feed on secondary consumers. Larger fish, predatory birds (like ospreys and kingfishers), and mammals (like otters and beavers) occupy these top trophic levels.

The Recyclers: Decomposers

Decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi, break down dead organic matter from all trophic levels, returning essential nutrients back into the ecosystem. This recycling process is vital for sustaining the entire food web.

The Vital Role of Freshwater Ecosystems

Beyond their intrinsic ecological value, freshwater ecosystems provide an array of indispensable services to humanity and the planet.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: Despite covering less than 1% of Earth’s surface, freshwater ecosystems harbor a disproportionately high number of species, making them crucial for global biodiversity.

- Water Supply: They are the primary source of drinking water for human populations, as well as water for agriculture, industry, and energy production.

- Climate Regulation: Wetlands, in particular, play a significant role in carbon sequestration, helping to mitigate climate change. They also influence local weather patterns through evaporation.

- Nutrient Cycling and Water Purification: Wetlands and riparian zones act as natural filters, removing pollutants and excess nutrients from water, thereby improving water quality downstream.

- Flood Control: Floodplains and wetlands absorb excess water during heavy rainfall, reducing the impact of floods on human settlements.

- Recreation and Cultural Value: Rivers, lakes, and wetlands offer opportunities for fishing, boating, swimming, birdwatching, and provide aesthetic beauty and cultural significance to many communities.

Major Threats to Freshwater Ecosystems

Despite their immense importance, freshwater ecosystems are among the most threatened on Earth. A confluence of human activities is pushing these vital systems to their limits, leading to declines in biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Pollution: A Toxic Tide

Pollution is arguably the most pervasive threat. It comes in many forms:

- Industrial Discharge: Factories release untreated or inadequately treated wastewater containing heavy metals, chemicals, and other toxins.

- Agricultural Runoff: Fertilizers and pesticides from farms wash into waterways, leading to eutrophication (excessive nutrient enrichment) and harmful algal blooms.

- Urban Wastewater: Sewage and stormwater runoff from cities introduce pathogens, pharmaceuticals, and microplastics.

- Plastic Pollution: Microplastics and larger plastic debris are ubiquitous, harming aquatic life and entering the food chain.

Habitat Loss and Degradation: Eroding Foundations

The physical alteration of freshwater habitats is widespread:

- Dams and Diversions: These structures alter natural flow regimes, block fish migration, and change water temperature and sediment transport.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: Paving over natural areas, channelizing rivers, and draining wetlands destroy critical habitats.

- Deforestation: Removal of riparian vegetation leads to increased erosion, sedimentation, and higher water temperatures.

Overexploitation: Draining the Well

The demand for freshwater resources often exceeds sustainable limits:

- Overfishing: Unsustainable fishing practices deplete fish stocks, disrupting food webs and ecosystem balance.

- Water Abstraction: Excessive withdrawal of water for agriculture, industry, and domestic use can dry up rivers, lower lake levels, and deplete groundwater aquifers.

Climate Change: A Shifting Balance

Global climate change exacerbates existing threats and introduces new challenges:

- Altered Precipitation Patterns: Leading to more frequent and intense droughts in some regions, and severe floods in others.

- Rising Water Temperatures: Affecting oxygen levels, species distribution, and increasing the risk of disease.

- Glacier Melt: Reducing long-term water supply for many river systems.

Invasive Species: Ecological Invaders

The introduction of non-native species, often unintentionally, can have devastating effects:

- Competition: Invasive species outcompete native species for resources.

- Predation: They can prey on native species that have no natural defenses.

- Habitat Alteration: Some invasive plants can drastically change the physical structure of an ecosystem. Examples include zebra mussels, carp, and water hyacinth.

Conservation and Stewardship: Protecting Our Lifelines

The challenges facing freshwater ecosystems are immense, but so too are the opportunities for conservation. Protecting these vital systems requires a multi-faceted approach involving individuals, communities, and governments.

- Sustainable Water Management: Implementing policies that promote efficient water use, reduce waste, and ensure equitable allocation of water resources. This includes investing in water-saving technologies in agriculture and industry.

- Pollution Control: Stricter regulations on industrial and agricultural discharges, improved wastewater treatment, and public awareness campaigns to reduce litter and chemical use.

- Habitat Restoration: Removing obsolete dams, restoring riparian vegetation, re-establishing natural flow regimes, and rehabilitating degraded wetlands.

- Protected Areas: Establishing and effectively managing protected areas for freshwater biodiversity, such as national parks and wildlife refuges.

- Controlling Invasive Species: Implementing measures to prevent the introduction of non-native species and managing existing invasive populations.

- Community Engagement: Educating the public about the importance of freshwater ecosystems and empowering local communities to participate in conservation efforts, such as river clean-ups and citizen science programs.

- International Cooperation: Many major river basins cross national borders, necessitating international agreements and collaborative efforts for effective management.

Conclusion

Freshwater ecosystems are far more than just sources of water, they are intricate tapestries of life, essential for the health of the planet and all its inhabitants. From the smallest plankton to the largest predators, every component plays a role in maintaining the delicate balance of these environments. The threats they face are significant and interconnected, but through informed action, responsible stewardship, and a collective commitment to conservation, it is possible to safeguard these invaluable lifelines for future generations. Understanding freshwater ecosystems is the first step towards protecting them, ensuring that the rivers continue to flow, the lakes remain vibrant, and the wetlands thrive.