The Vital Art of Conservation: Protecting Earth’s Living Tapestry

The Earth is a vibrant, intricate tapestry woven from countless species and ecosystems. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every thread plays a role in maintaining the planet’s delicate balance. However, this magnificent tapestry is under unprecedented strain. This is where the crucial discipline of conservation steps in: a science and an art dedicated to protecting and managing nature, ensuring its health and vitality for generations to come. Conservation is not just about saving charismatic megafauna; it is about safeguarding the very life support systems that sustain all life, including humanity.

What is Conservation? The Core Principles

At its heart, conservation is the wise management and protection of natural resources, including plants, animals, and their habitats. It is a proactive approach to prevent degradation and loss, while also working to heal past damage. This multifaceted discipline operates on several core principles, each essential for a holistic approach to environmental stewardship.

The foundational ideas can be summarized as:

- Protect Species: This principle focuses on preventing the extinction of individual species and maintaining genetic diversity within populations. It involves identifying endangered species, understanding the threats they face, and implementing direct measures for their survival. For example, establishing protected breeding grounds for migratory birds or creating anti-poaching units for rhinos are direct applications of this principle.

- Restore Ecosystems: Many natural areas have been degraded or destroyed by human activities. This principle aims to reverse that damage, bringing ecosystems back to a healthy, functional state. This could involve replanting forests on deforested land, cleaning up polluted rivers, or reintroducing native species to areas where they have been extirpated. A successful restoration project might transform a barren mining site into a thriving wetland.

- Sustainable Use: Recognizing that humans are an integral part of most ecosystems, this principle advocates for using natural resources in a way that meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It is about finding a balance between human development and environmental protection. Sustainable forestry, responsible fishing practices, and eco-tourism are excellent examples of sustainable use, allowing human interaction with nature without depleting its resources.

These principles are interconnected, forming a comprehensive framework for addressing the complex challenges facing our natural world.

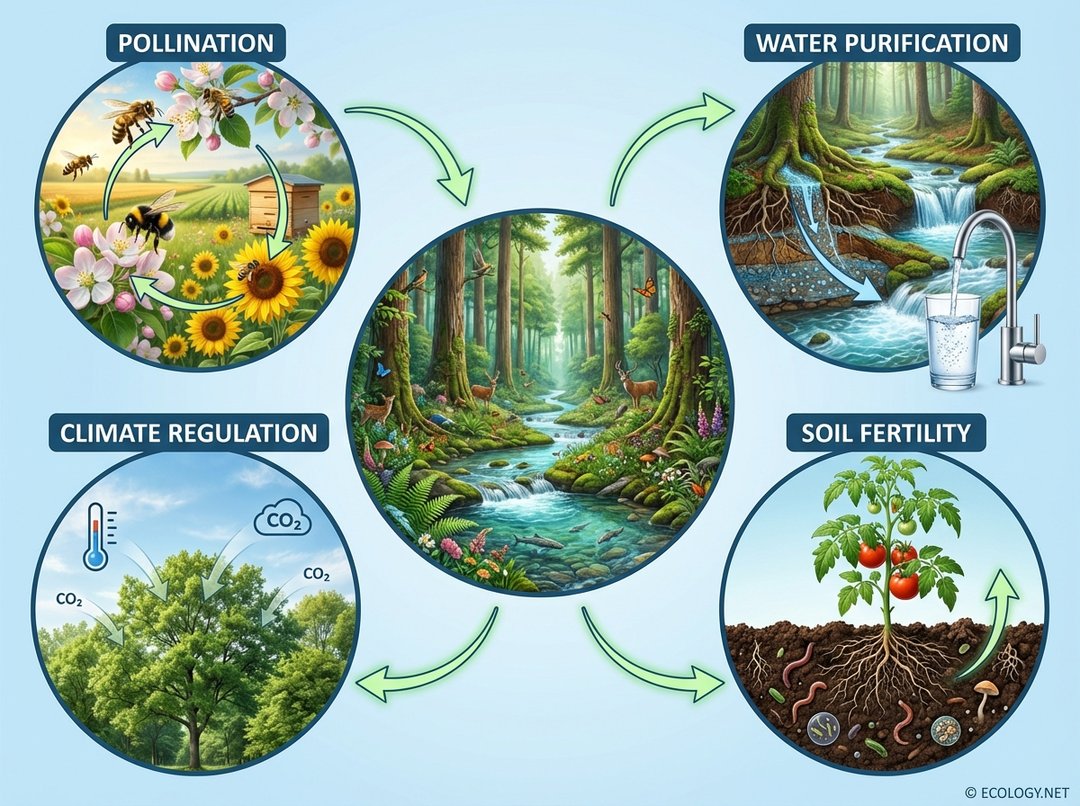

Why Conserve? The Value of Biodiversity: Ecosystem Services

The question “Why conserve?” often elicits responses about beauty or ethical responsibility. While these are valid, the most compelling answer lies in the invaluable “ecosystem services” that biodiversity provides. These are the direct and indirect benefits that humans receive from ecosystems, often taken for granted until they are lost.

Consider these vital services:

- Pollination: Bees, butterflies, bats, and other animals are essential for pollinating crops and wild plants. Without them, a significant portion of our food supply, including fruits, vegetables, and nuts, would drastically decline. Imagine a world without apples, almonds, or coffee.

- Water Purification: Forests, wetlands, and healthy soils act as natural filters, removing pollutants from water as it flows through the landscape. This natural process provides clean drinking water, reduces the need for expensive artificial treatment plants, and supports aquatic life. For instance, the Catskill Mountains watershed provides much of New York City’s drinking water, a testament to natural filtration.

- Climate Regulation: Forests and oceans absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas, helping to regulate global temperatures and mitigate climate change. Trees also influence local climates by providing shade and releasing moisture, reducing urban heat island effects.

- Soil Fertility: Healthy soil, teeming with microorganisms, fungi, and invertebrates like earthworms, is the foundation of agriculture. These organisms break down organic matter, cycle nutrients, and improve soil structure, making it fertile and productive for growing food.

- Disease Regulation: Diverse ecosystems can help regulate the spread of diseases by supporting a wide range of species that act as buffers or competitors to disease vectors.

- Recreation and Cultural Value: Natural landscapes provide spaces for recreation, spiritual renewal, and cultural inspiration, contributing significantly to human well-being and quality of life.

The loss of biodiversity directly undermines these services, leading to economic costs, reduced quality of life, and increased vulnerability to environmental changes.

Threats to Biodiversity: The Challenges We Face

Understanding the “why” of conservation necessitates understanding the “what” that threatens biodiversity. The primary drivers of species extinction and ecosystem degradation are largely anthropogenic, meaning they originate from human activities.

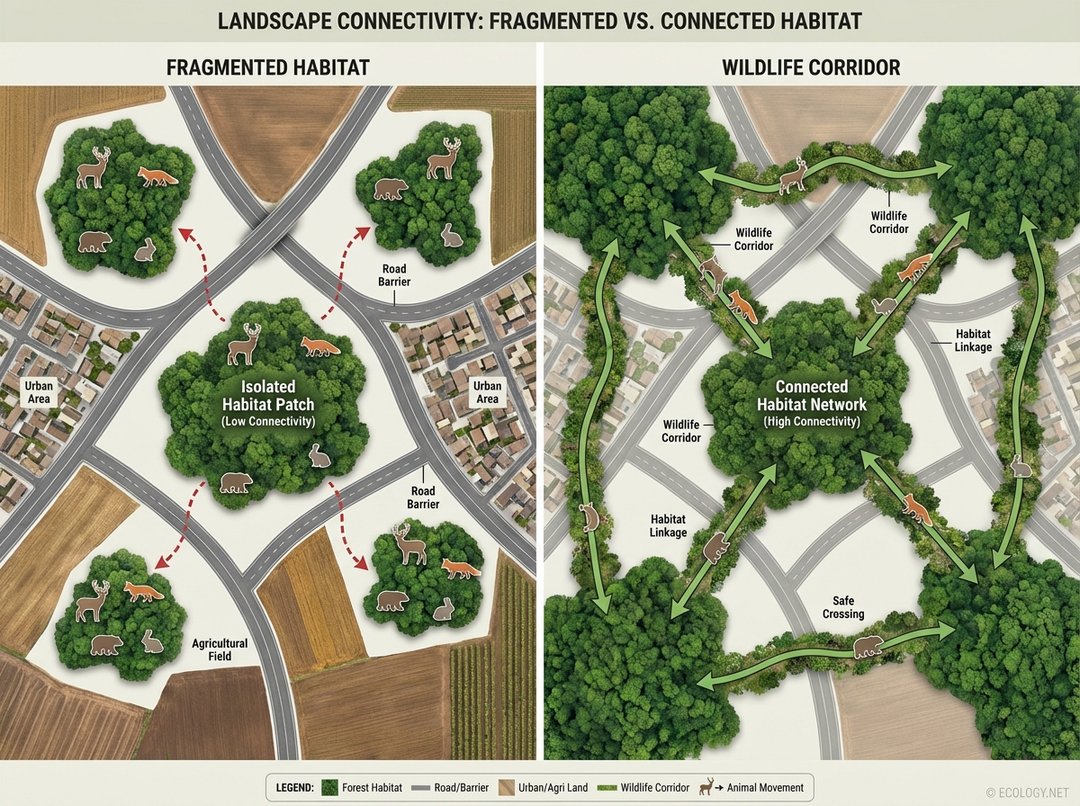

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: This is arguably the greatest threat. As human populations expand, natural habitats are converted for agriculture, urban development, infrastructure, and resource extraction. When habitats are not just lost but also broken into smaller, isolated patches, it is called fragmentation. This isolates populations, making them more vulnerable to local extinction and reducing genetic diversity.

- Climate Change: Rising global temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events are forcing species to adapt or migrate at unprecedented rates. Many cannot keep pace, leading to population declines and shifts in ecosystem boundaries. Coral bleaching events, for example, are a direct consequence of warming oceans.

- Pollution: Air, water, and soil pollution from industrial activities, agriculture, and waste disposal poison ecosystems and harm wildlife. Pesticides, plastics, heavy metals, and nutrient runoff can have devastating effects, from direct toxicity to long-term reproductive issues.

- Overexploitation: The unsustainable harvesting of wild plants and animals for food, timber, medicine, or the pet trade can deplete populations faster than they can reproduce. Overfishing, illegal logging, and poaching are prime examples.

- Invasive Species: The introduction of non-native species, either accidentally or intentionally, can outcompete native species for resources, prey upon them, or introduce diseases, leading to declines or extinctions of indigenous flora and fauna. The spread of the emerald ash borer, devastating ash trees across North America, is a stark illustration.

Strategies and Approaches to Conservation

Addressing these complex threats requires a diverse toolkit of strategies, ranging from local actions to international agreements. Conservation is a dynamic field, constantly evolving to meet new challenges.

Protected Areas: Cornerstones of Conservation

Establishing national parks, wildlife refuges, marine protected areas, and wilderness areas is a fundamental strategy. These designated zones aim to safeguard critical habitats and species from human disturbance. Examples include the vast national parks of the United States, the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, or the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park in Australia, each preserving unique and vital ecosystems. The effectiveness of protected areas often depends on their size, management, and connectivity to other natural spaces.

Species-Specific Conservation: Targeted Interventions

When a particular species is critically endangered, conservation efforts often focus directly on its survival. This can involve:

- Captive Breeding Programs: Rearing endangered animals in zoos or specialized facilities to increase their numbers, such as the successful efforts for the California condor or the giant panda.

- Reintroduction Programs: Releasing captive-bred or translocated wild individuals back into their native habitats to establish new populations or bolster existing ones. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park is a classic example.

- Habitat Restoration for Specific Species: Tailoring restoration efforts to meet the unique needs of a threatened species, like creating specific nesting sites for sea turtles.

Landscape Ecology and Connectivity

As habitats become increasingly fragmented, understanding how species move across landscapes is crucial. Landscape ecology studies the patterns and interactions between ecosystems in a region.

A key solution to fragmentation is the creation of wildlife corridors. These are strips of natural habitat that connect isolated patches, allowing animals to move safely between them. Corridors can be natural features like riverbanks or mountain ranges, or they can be specially designed structures such as underpasses or overpasses across highways. By facilitating movement, corridors help maintain genetic diversity, allow species to access food and mates, and enable populations to adapt to changing environmental conditions. For instance, efforts to connect fragmented forest patches in areas like the Yellowstone to Yukon region aim to create a vast, continuous habitat for large mammals.

Community-Based Conservation: Empowering Local Stewards

Recognizing that local communities often live closest to and depend most directly on natural resources, community-based conservation involves engaging these populations in conservation efforts. By providing economic incentives, education, and decision-making power, these initiatives foster a sense of ownership and responsibility, leading to more sustainable outcomes. Indigenous communities, with their deep traditional ecological knowledge, often play a pivotal role in these programs.

Policy and Legislation: The Framework for Protection

Effective conservation requires strong legal and policy frameworks at local, national, and international levels.

- National Laws: Legislation like the Endangered Species Act in the United States or similar acts in other countries provide legal protection for threatened species and their habitats.

- International Agreements: Treaties such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) aim to coordinate global efforts to protect biodiversity and regulate the trade of endangered species.

Restoration Ecology: Healing Degraded Lands

Beyond simply protecting what remains, restoration ecology actively works to repair and rebuild ecosystems that have been damaged. This can involve:

- Reforestation and Afforestation: Planting trees in areas that were once forested or creating new forests where none existed.

- Wetland Restoration: Recreating or rehabilitating wetlands that have been drained or filled, bringing back their vital functions for water filtration and wildlife habitat.

- Mine Site Reclamation: Transforming former mining sites into productive ecosystems, often involving reshaping land, replacing topsoil, and planting native vegetation.

Sustainable Practices Across Sectors

Integrating conservation principles into everyday human activities is paramount.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Practices like organic farming, agroforestry, and reduced tillage minimize chemical use, conserve soil, and support biodiversity on farms.

- Sustainable Forestry: Managing forests for long-term health and productivity, ensuring that timber harvesting does not deplete forest resources or harm ecosystem functions.

- Sustainable Fisheries: Implementing quotas, regulating fishing gear, and establishing marine protected areas to prevent overfishing and allow fish populations to recover.

The Role of Everyone in Conservation

Conservation is not solely the domain of scientists, policymakers, or park rangers. Every individual has a role to play in safeguarding our planet’s biodiversity.

- Informed Consumer Choices: Supporting businesses that practice sustainability, choosing sustainably sourced products, and reducing consumption can significantly lessen environmental impact.

- Reducing Your Footprint: Conserving energy, reducing waste, recycling, and opting for sustainable transportation methods all contribute to a healthier planet.

- Education and Advocacy: Learning about local and global conservation issues and advocating for policies that protect nature can create powerful collective change.

- Volunteering: Participating in local clean-ups, habitat restoration projects, or citizen science initiatives directly contributes to conservation efforts.

A Future Forged in Conservation

The challenges facing biodiversity are immense, but so too is the human capacity for innovation, cooperation, and care. Conservation is an ongoing journey, a testament to our understanding that humanity’s fate is inextricably linked to the health of the natural world. By embracing its core principles, implementing diverse strategies, and fostering a collective sense of responsibility, we can ensure that Earth’s living tapestry continues to thrive, providing beauty, wonder, and essential life support for all who call this planet home. The future of conservation is not just about protecting nature from humans, but about integrating humans into a sustainable relationship with nature, for the benefit of all life.