Imagine our planet as a vast, living bank account. This account doesn’t hold money, but something far more fundamental: the capacity to sustain life. This crucial concept is known as biocapacity. It represents the Earth’s remarkable ability to regenerate the resources we consume and absorb the waste we generate. Understanding biocapacity is not just for scientists; it is essential for every individual who shares this planet, as it holds the key to our collective future.

What Exactly is Biocapacity?

At its core, biocapacity is the biological productivity of a given area. Think of it as nature’s supply side. It measures the capacity of ecosystems to produce useful biological materials and to absorb the waste materials generated by humans, particularly carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels. It is the planet’s inherent ability to replenish and process, a vital service that often goes unnoticed until it is stretched thin.

Consider a forest. Its biocapacity includes its ability to grow timber, provide habitat for wildlife, regulate water cycles, and absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A fertile field’s biocapacity is its ability to grow crops year after year. The ocean’s biocapacity includes its fish stocks and its role in nutrient cycling.

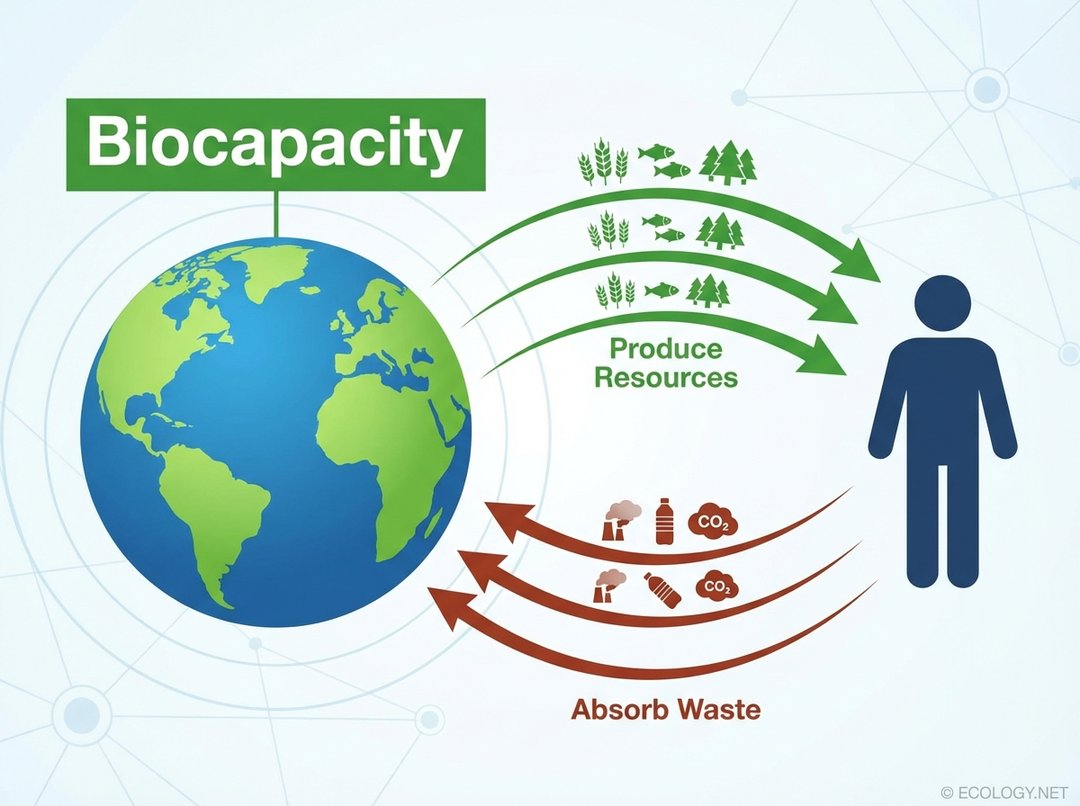

This illustrative diagram helps us visualize biocapacity. Arrows emanate from the Earth, representing the production of vital resources like food, timber, and fresh water, all flowing towards human consumption. Simultaneously, arrows point back to the Earth from human activities, symbolizing the absorption of our waste products, such as carbon dioxide and pollutants. This continuous cycle highlights the Earth’s dual role as both provider and cleanser, a role that defines its biocapacity.

The Building Blocks of Biocapacity: Where Does it Come From?

Earth’s biocapacity is not a single, uniform entity. It is a mosaic of different productive land and sea areas, each contributing in its own unique way. To truly grasp biocapacity, we must understand its components.

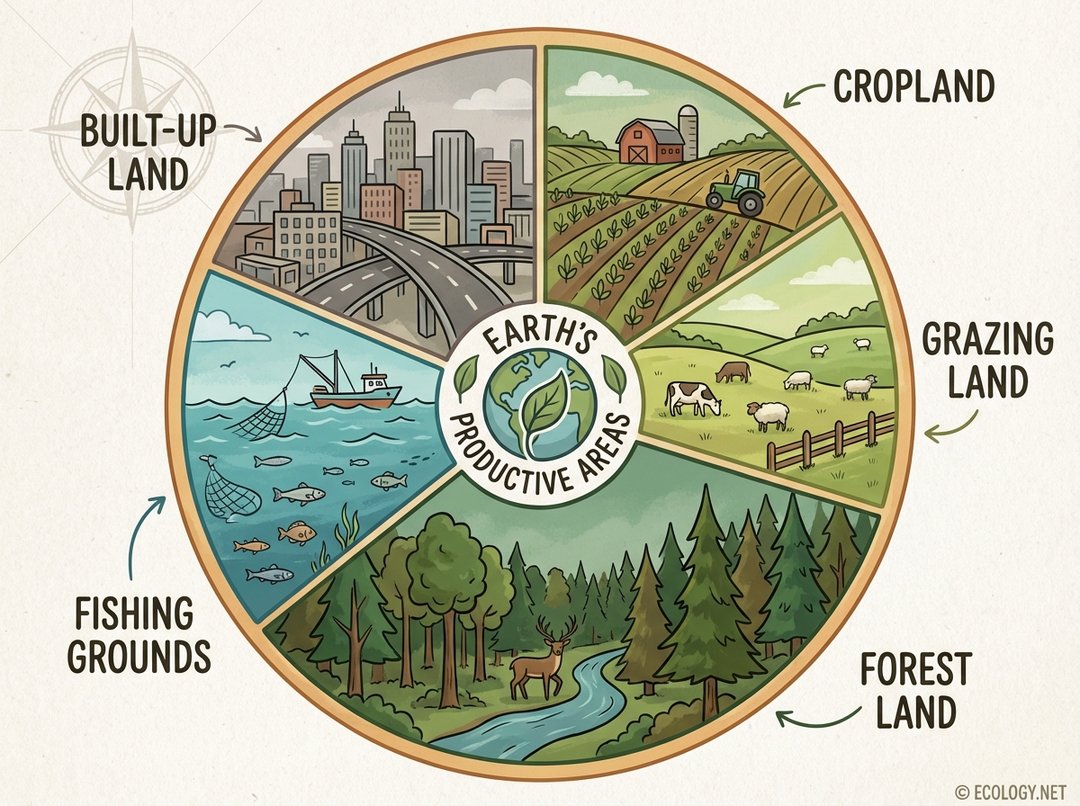

This illustration breaks down the Earth’s productive surface into distinct categories, each playing a critical role in our planet’s overall biocapacity:

- Cropland: These are the agricultural areas we use to grow food, feed for livestock, and fiber crops like cotton. They are among the most biologically productive areas on Earth and are essential for human sustenance. Think of the vast wheat fields of the American Midwest or the rice paddies of Asia.

- Grazing Land: Pastures and rangelands where livestock graze. These areas support meat and dairy production, providing another crucial food source. The grasslands of the African savanna or the sheep farms of New Zealand are prime examples.

- Forest Land: Forests provide timber, fuelwood, and other forest products. Crucially, they also absorb significant amounts of carbon dioxide, regulate climate, and support immense biodiversity. From the Amazon rainforest to the boreal forests of Canada, these ecosystems are vital.

- Fishing Grounds: These are the marine and freshwater areas from which we harvest fish and other aquatic products. Healthy oceans, lakes, and rivers are critical for protein sources and ecosystem balance. Consider the rich fishing grounds off the coast of Peru or the salmon rivers of Alaska.

- Built-up Land: This category includes urban areas, infrastructure, and industrial zones. While essential for human society, built-up land represents productive areas that have been converted and are no longer available for producing biological resources or absorbing waste in the same way. A new highway or a sprawling city reduces the available biocapacity.

Each of these components contributes to the total biocapacity of a region or the entire planet. The health and extent of these areas directly determine how much nature can provide and process for us.

Why Biocapacity Matters: Living Within Our Means

Understanding biocapacity is not an academic exercise; it is fundamental to our survival and prosperity. It provides a critical benchmark for sustainability. When our demand for resources and waste absorption exceeds the Earth’s biocapacity, we enter a state of ecological overshoot.

Imagine that bank account again. If you consistently withdraw more money than you deposit, you eventually run into debt. In ecological terms, this debt means depleting natural capital: cutting down forests faster than they can regrow, overfishing oceans, emitting more carbon dioxide than ecosystems can absorb, and depleting freshwater reserves. This is not sustainable.

The consequences of exceeding biocapacity are far-reaching:

- Resource Scarcity: Depletion of fish stocks, timber, and freshwater can lead to conflicts and economic instability.

- Climate Change: When carbon emissions exceed the Earth’s absorption capacity, greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere, driving global warming and its associated impacts.

- Biodiversity Loss: Habitat destruction and pollution, often driven by resource extraction, lead to the extinction of species, weakening ecosystems and their ability to provide services.

- Land Degradation: Overgrazing, unsustainable farming practices, and deforestation can lead to soil erosion, desertification, and reduced agricultural productivity.

In essence, biocapacity tells us how much “nature” we have available. When we compare it to our ecological footprint, which measures how much nature we demand, we get a clear picture of our relationship with the planet. A country with a large ecological footprint and low biocapacity is highly dependent on resources from other regions or is actively depleting its own natural capital.

Measuring the Earth’s Capacity: Global Hectares

To make biocapacity a practical tool for analysis and policy, scientists have developed a standardized unit of measurement: the global hectare (gha). A global hectare is a biologically productive hectare with world average productivity. This standardization allows for direct comparison of biocapacity and ecological footprints across different land types and countries.

Here is how it works:

- Each type of productive land or sea area (cropland, forest, etc.) is assigned an equivalence factor based on its relative productivity. For example, a hectare of highly productive cropland will have a higher equivalence factor than a hectare of less productive grazing land.

- The actual area of each land type is multiplied by its equivalence factor to convert it into global hectares. This accounts for the fact that not all hectares are equally productive.

This standardized unit allows us to answer questions like: “How many global hectares does it take to support the average person’s lifestyle?” or “Does a country have enough biocapacity within its borders to meet its population’s demands?” It provides a common language for discussing our planet’s limits.

Global Biocapacity Trends and Challenges

The global picture of biocapacity reveals some sobering trends. While the Earth’s total biocapacity has remained relatively stable, the biocapacity available per person has been steadily declining. This is primarily due to two factors:

- Population Growth: As the human population increases, the fixed amount of global biocapacity must be shared among more individuals, inevitably reducing the per capita share.

- Land Degradation: Human activities like deforestation, unsustainable agriculture, pollution, and urbanization reduce the overall productivity of ecosystems, effectively shrinking the total biocapacity available.

Current estimates suggest that humanity is using the equivalent of 1.7 Earths to sustain its current lifestyle. This means we are in significant ecological overshoot, drawing down our natural capital faster than it can regenerate. This deficit is not sustainable in the long term.

Major challenges to maintaining and enhancing biocapacity include:

- Unsustainable Consumption Patterns: High consumption rates in many parts of the world place immense pressure on natural resources.

- Climate Change: Altered weather patterns, extreme events, and rising sea levels can severely impact the productivity of croplands, forests, and fishing grounds.

- Biodiversity Loss: The loss of species can destabilize ecosystems, reducing their resilience and overall biocapacity.

- Inefficient Resource Use: Wasteful practices in food production, energy consumption, and manufacturing further exacerbate the demand on biocapacity.

Enhancing and Protecting Our Planet’s Biocapacity

The good news is that understanding biocapacity empowers us to make informed choices and implement solutions. Protecting and enhancing Earth’s biocapacity is not just about conservation; it is about smart resource management and sustainable living.

Key strategies include:

- Sustainable Agriculture: Adopting practices that improve soil health, reduce water use, minimize pesticide reliance, and increase yields without degrading land. Examples include organic farming, agroforestry, and precision agriculture.

- Forest Management and Reforestation: Protecting existing forests, preventing illegal logging, and actively planting new trees to restore degraded areas. This enhances carbon absorption and biodiversity.

- Marine Conservation: Establishing marine protected areas, regulating fishing practices to prevent overfishing, and reducing ocean pollution to allow marine ecosystems to recover and thrive.

- Efficient Urban Planning: Designing cities that minimize sprawl, promote green spaces, encourage public transportation, and reduce the conversion of productive land.

- Reducing Consumption and Waste: Shifting towards a circular economy where products are reused, repaired, and recycled, thereby reducing the demand for new resources and minimizing waste.

- Transition to Renewable Energy: Moving away from fossil fuels to sources like solar, wind, and hydro power dramatically reduces our carbon footprint, lessening the burden on the Earth’s carbon absorption biocapacity.

- Dietary Shifts: Promoting diets that are less resource intensive, such as reducing meat consumption, can significantly lower the demand on grazing lands and croplands.

Every action, from individual choices to global policies, contributes to either depleting or replenishing our planet’s vital biocapacity.

Conclusion: Our Shared Responsibility

Biocapacity is more than just an ecological term; it is a fundamental concept that defines the limits and possibilities of human civilization on Earth. It is the planet’s generous offer of resources and its tireless work in cleaning up after us. By understanding what biocapacity is, where it comes from, and why it matters, we gain a clearer perspective on our place in the natural world.

Living within the Earth’s biocapacity is not about deprivation; it is about living intelligently, efficiently, and sustainably. It is about recognizing that our well-being is inextricably linked to the health of our planet. The future depends on our collective ability to respect these natural limits and to become responsible stewards of Earth’s invaluable biological capital.