Unveiling Ecology: The Science of Life’s Interconnected Web

Imagine a world where every living thing, from the smallest microbe to the largest whale, is intricately linked to its surroundings and to every other organism. This isn’t a fantasy; it is the fundamental reality of our planet, and the scientific discipline dedicated to understanding these profound connections is called ecology. Ecology is far more than just “environmental science”; it is the study of how organisms interact with each other and with their non-living environment, revealing the complex dance of life that sustains our world.

Understanding ecology is not merely an academic exercise. It is crucial for comprehending global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion. By exploring the principles of ecology, we gain insights into how natural systems function, how human activities impact them, and what steps are necessary to foster a sustainable future.

The Building Blocks of Life: Levels of Ecological Organization

To grasp the vastness of ecological study, it helps to break it down into manageable levels. Ecologists analyze life at various scales, each providing a unique perspective on the grand tapestry of nature. These hierarchical levels allow scientists to focus on specific interactions while still recognizing their place within the larger system.

- Individual: The most basic unit of ecology is a single organism, such as a lone deer foraging in a meadow. An individual’s survival, reproduction, and behavior are central to understanding its role.

- Population: This refers to a group of individuals of the same species living in the same area at the same time. For example, all the deer in a particular forest constitute a population. Ecologists study population size, density, distribution, and growth patterns.

- Community: A community encompasses all the different populations of various species that live and interact in a particular area. This includes the deer, the trees they browse on, the wolves that might prey on them, and countless other plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. Interactions like predation, competition, and symbiosis are key here.

- Ecosystem: Moving beyond just living organisms, an ecosystem includes all the living components (the community) and the non-living physical and chemical factors of their environment. This means adding elements like sunlight, water, soil, and temperature to our forest scene. An ecosystem is a dynamic system where energy flows and nutrients cycle.

- Biosphere: This is the largest and most inclusive level, representing the sum of all ecosystems on Earth. It is the global ecological system integrating all living beings and their relationships, including their interaction with the elements of the lithosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere. Essentially, it is the entire portion of Earth where life exists.

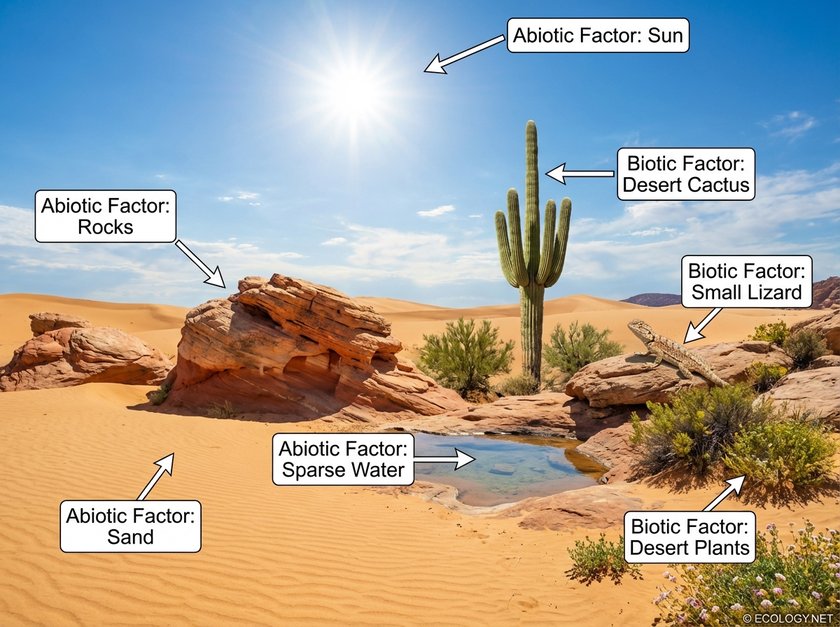

The Fabric of Ecosystems: Abiotic and Biotic Factors

Every ecosystem, whether a bustling rainforest or a barren desert, is composed of two fundamental types of components: living and non-living. Understanding the interplay between these elements is crucial for comprehending how an ecosystem functions and sustains itself.

- Abiotic Factors: These are the non-living physical and chemical elements of an ecosystem. They set the stage for life and dictate which organisms can thrive in a particular environment. Examples include:

- Sunlight: The primary energy source for most ecosystems.

- Water: Essential for all life processes, its availability often limits species distribution.

- Temperature: Influences metabolic rates and the geographical range of species.

- Soil: Provides nutrients, anchorage for plants, and habitat for countless organisms.

- Atmosphere: Supplies gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide, crucial for respiration and photosynthesis.

- pH: The acidity or alkalinity of soil and water affects nutrient availability and organism survival.

- Biotic Factors: These are all the living or once-living components of an ecosystem. They are the organisms themselves and their interactions. Examples include:

- Producers (Autotrophs): Organisms, primarily plants and algae, that produce their own food through photosynthesis, converting sunlight into energy.

- Consumers (Heterotrophs): Organisms that obtain energy by eating other organisms. These can be herbivores (eating plants), carnivores (eating animals), or omnivores (eating both).

- Decomposers: Organisms like bacteria and fungi that break down dead organic matter, returning nutrients to the soil and water for producers to reuse.

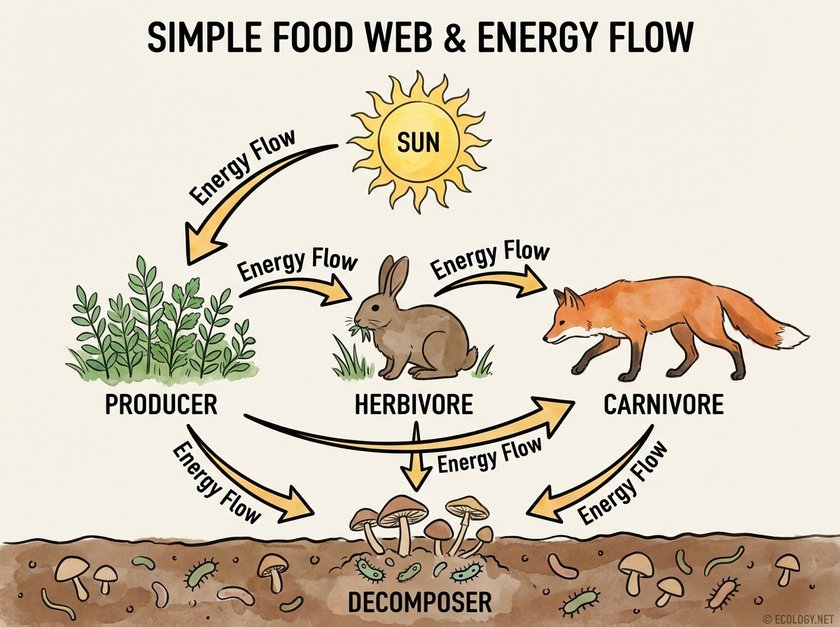

The Engine of Life: Energy Flow and Food Webs

Life requires energy, and in nearly all ecosystems, that energy originates from the sun. Ecology helps us trace the path of this energy as it moves through different organisms, illustrating the fundamental interconnectedness of life. This movement of energy is often depicted through food chains and, more realistically, through complex food webs.

The journey of energy begins with:

- Producers: Green plants, algae, and some bacteria capture solar energy through photosynthesis, converting it into chemical energy stored in organic compounds. They form the base of every food web.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Animals like rabbits, deer, and insects obtain energy by eating producers. They are the first link in the consumer chain.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores/Omnivores): These organisms feed on primary consumers. A fox eating a rabbit is an example of a secondary consumer.

- Tertiary Consumers: These carnivores eat secondary consumers. A hawk eating a snake that ate a mouse would be a tertiary consumer.

- Decomposers: Fungi and bacteria play a vital role by breaking down dead organic matter from all trophic levels. This process releases nutrients back into the ecosystem, making them available for producers, thus completing the cycle of matter, though not energy.

It is important to note that energy flow is unidirectional and inefficient. At each transfer between trophic levels, a significant amount of energy, typically around 90 percent, is lost as heat. This explains why there are fewer top predators than herbivores in an ecosystem; there simply isn’t enough energy to support a large population at higher trophic levels.

Beyond the Basics: Deeper Ecological Concepts

While the foundational concepts provide a strong starting point, ecology delves much deeper into the intricate workings of nature, exploring complex interactions and large-scale patterns.

Population Dynamics and Limiting Factors

Populations do not grow indefinitely. Their size and distribution are influenced by a variety of factors. Population ecology examines birth rates, death rates, immigration, and emigration. It also investigates limiting factors, which are environmental conditions that restrict population growth. These can be:

- Density-dependent factors: Factors whose impact increases with population density, such as competition for resources, predation, disease, and parasitism. For instance, a dense deer population might experience increased spread of disease or more intense competition for food.

- Density-independent factors: Factors that affect a population regardless of its density, often abiotic in nature. Examples include natural disasters like floods, fires, or extreme weather events. A severe drought can impact a plant population regardless of how sparse or dense it is.

Community Interactions: The Web of Relationships

Within a community, species interact in myriad ways, shaping each other’s evolution and distribution. These interactions are categorized by their effects on the participating species:

- Competition: Occurs when two or more species require the same limited resource, such as food, water, or space. This can be intense, leading to one species outcompeting another, or it can drive species to specialize and utilize different aspects of the resource.

- Predation: An interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and consumes another organism, the prey. This relationship is a powerful evolutionary force, driving adaptations in both predator (e.g., speed, camouflage) and prey (e.g., warning coloration, defensive behaviors).

- Herbivory: A specific type of predation where an animal consumes plants. Plants have evolved various defenses, from thorns to chemical toxins, to deter herbivores.

- Symbiosis: Close and long-term interactions between two different species.

- Mutualism: Both species benefit from the interaction. For example, bees pollinating flowers, where the bee gets nectar and the flower gets pollinated.

- Commensalism: One species benefits, and the other is neither helped nor harmed. An example is barnacles attaching to whales; the barnacles get a place to live and filter feed, while the whale is largely unaffected.

- Parasitism: One species, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host. Ticks feeding on a mammal are a classic example.

Ecological Succession: Nature’s Renewal

Ecosystems are not static; they are constantly changing. Ecological succession describes the process of change in the species structure of an ecological community over time. This can occur after a disturbance, like a forest fire or volcanic eruption, or in newly formed habitats, such as bare rock exposed by a retreating glacier.

- Primary Succession: Begins in an area where no soil exists, such as new volcanic rock or sand dunes. Pioneer species, like lichens and mosses, colonize first, slowly breaking down rock and creating rudimentary soil, allowing other plants to establish.

- Secondary Succession: Occurs in an area where a disturbance has removed most of the vegetation but the soil remains intact, such as after a forest fire or abandoned agricultural field. This process is generally faster than primary succession because of the pre-existing soil and seed bank.

Eventually, if left undisturbed, many successional pathways lead to a relatively stable, mature community known as a climax community, though this concept is now viewed as more dynamic and less fixed than once thought.

Biomes: Global Patterns of Life

On a grand scale, Earth’s diverse climates and geographies give rise to distinct large-scale ecosystems called biomes. These are characterized by their dominant vegetation types and the adaptations of the organisms living within them. Examples include:

- Tropical Rainforests: High rainfall, warm temperatures, incredible biodiversity.

- Deserts: Low rainfall, extreme temperatures, specialized drought-adapted plants and animals.

- Grasslands (Savannas, Prairies): Dominated by grasses, often with grazing animals, moderate rainfall.

- Temperate Forests: Deciduous trees, distinct seasons, moderate rainfall.

- Tundra: Cold, treeless plains, permafrost, low-growing vegetation.

- Aquatic Biomes: Oceans, lakes, rivers, estuaries, each with unique physical and biological characteristics.

Understanding biomes helps us appreciate the vast diversity of life on Earth and the specific environmental conditions that shape it.

Biodiversity: The Web of Life’s Richness

Biodiversity, or biological diversity, refers to the variety of life on Earth at all its levels, from genes to ecosystems. It is a cornerstone of ecological health and resilience. A highly biodiverse ecosystem is generally more stable and productive, better able to withstand disturbances, and provides a wider array of ecosystem services.

Ecosystem services are the many benefits that humans freely gain from the natural environment and from properly functioning ecosystems. These include clean air and water, pollination of crops, climate regulation, nutrient cycling, and aesthetic beauty.

The loss of biodiversity, driven by habitat destruction, pollution, climate change, and overexploitation, is one of the most pressing ecological crises of our time, threatening the very services that support human well-being.

Ecology in Action: Human Impact and Conservation

Humans are an integral part of the global ecosystem, and our activities have profound ecological consequences. From altering landscapes for agriculture and urbanization to releasing pollutants and greenhouse gases, our footprint is undeniable. Ecology provides the framework for understanding these impacts and developing solutions.

- Conservation Biology: This applied field uses ecological principles to protect and restore biodiversity. It involves strategies like establishing protected areas, managing endangered species, and restoring degraded habitats.

- Sustainability: A core concept in modern ecology, sustainability aims to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This requires balancing economic development with environmental protection and social equity.

- Ecological Restoration: The practice of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed. This often involves reintroducing native species, removing invasive ones, and restoring natural hydrological or fire regimes.

The Enduring Importance of Ecology

Ecology is not just a collection of facts about nature; it is a way of thinking about the world, recognizing the profound interconnectedness of all things. It teaches us that every action, no matter how small, can ripple through an ecosystem, affecting countless other organisms and processes. From the intricate dance of predator and prey to the global cycles of carbon and water, ecology reveals the elegant complexity that sustains life on Earth.

By embracing ecological understanding, we empower ourselves to make informed decisions, both individually and collectively, that foster a healthier, more resilient planet. The future of life, including our own, depends on our ability to live in harmony with the natural world, guided by the timeless principles of ecology.