The Living Earth Beneath Our Feet: What is Soil, and Why Should We Care?

Imagine a world without food, clean water, or breathable air. While this might sound like a dystopian novel, the health of our planet, and indeed our very existence, hinges on something often overlooked: soil. Far from being mere dirt, soil is a complex, living ecosystem, a dynamic foundation that supports nearly all life on Earth. Understanding its intricate nature is the first step towards appreciating the critical importance of soil conservation.

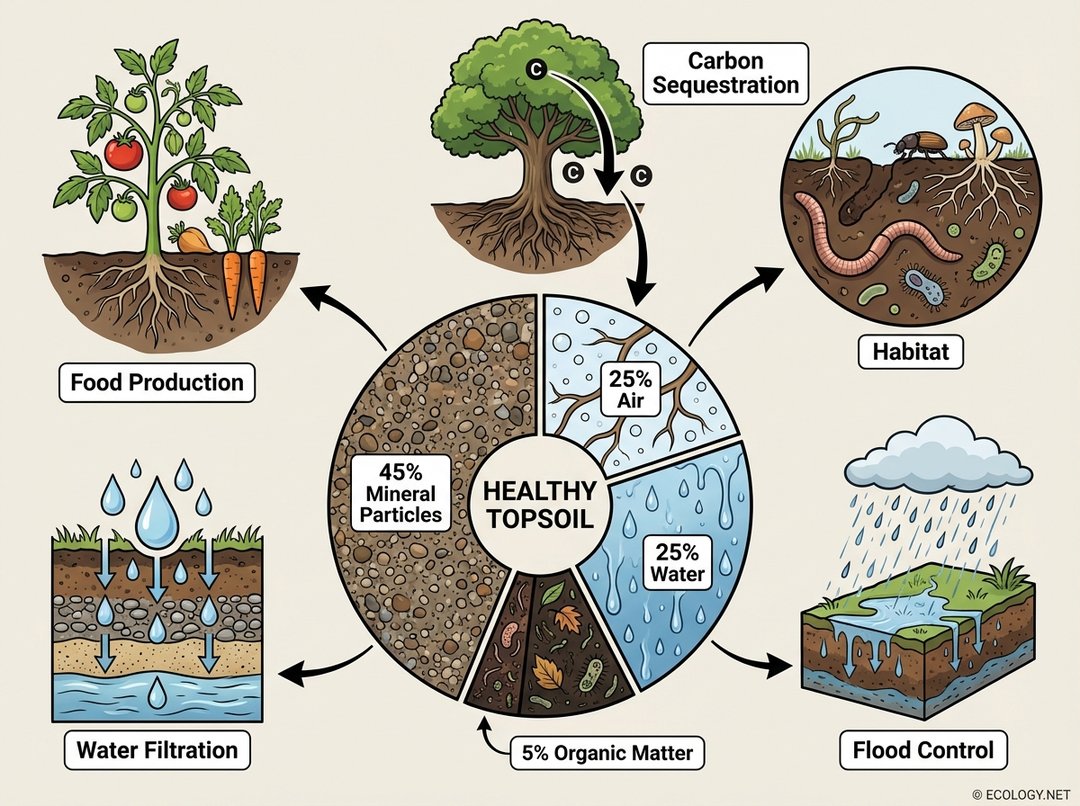

At its core, healthy topsoil is a finely balanced mixture, a recipe for life that has been perfected over millennia. It is not just inert particles, but a vibrant matrix where minerals, water, air, and organic matter intertwine to perform essential functions.

As this diagram illustrates, a typical healthy topsoil profile consists of:

- 45% Mineral Particles: These are the weathered fragments of rock, providing the structural backbone and essential nutrients like phosphorus, potassium, and calcium.

- 25% Water: Held within the soil pores, water is vital for plant growth, nutrient transport, and microbial activity.

- 25% Air: Also residing in the soil pores, air provides oxygen for roots and countless soil organisms.

- 5% Organic Matter: This seemingly small percentage is perhaps the most crucial. Composed of decaying plant and animal material, it acts like a sponge, holding water and nutrients, improving soil structure, and feeding the vast underground food web.

These components work in concert to deliver five crucial functions that underpin our world:

- Food Production: Soil is the medium in which nearly all our food crops grow, providing the nutrients and support necessary for plants to thrive.

- Water Filtration: As water percolates through soil layers, it is naturally filtered, removing pollutants and recharging groundwater supplies.

- Carbon Sequestration: Healthy soils are massive carbon sinks, storing vast amounts of carbon in their organic matter, thereby playing a vital role in regulating Earth’s climate.

- Habitat: A single teaspoon of healthy soil can contain billions of microorganisms, along with insects, worms, and other creatures, forming a complex ecosystem essential for nutrient cycling and soil health.

- Flood Control: Well-structured soil with high organic matter acts like a sponge, absorbing rainfall and reducing surface runoff, which mitigates floods and prevents erosion.

Given these indispensable roles, it becomes clear that the degradation of soil is not merely an agricultural problem, but a global crisis impacting everything from climate stability to human health.

The Silent Crisis: Threats to Our Soil

Despite its resilience, soil is surprisingly fragile and susceptible to various threats, many of which are exacerbated by human activities. The most visible and destructive of these is erosion.

Erosion: The Great Destroyer

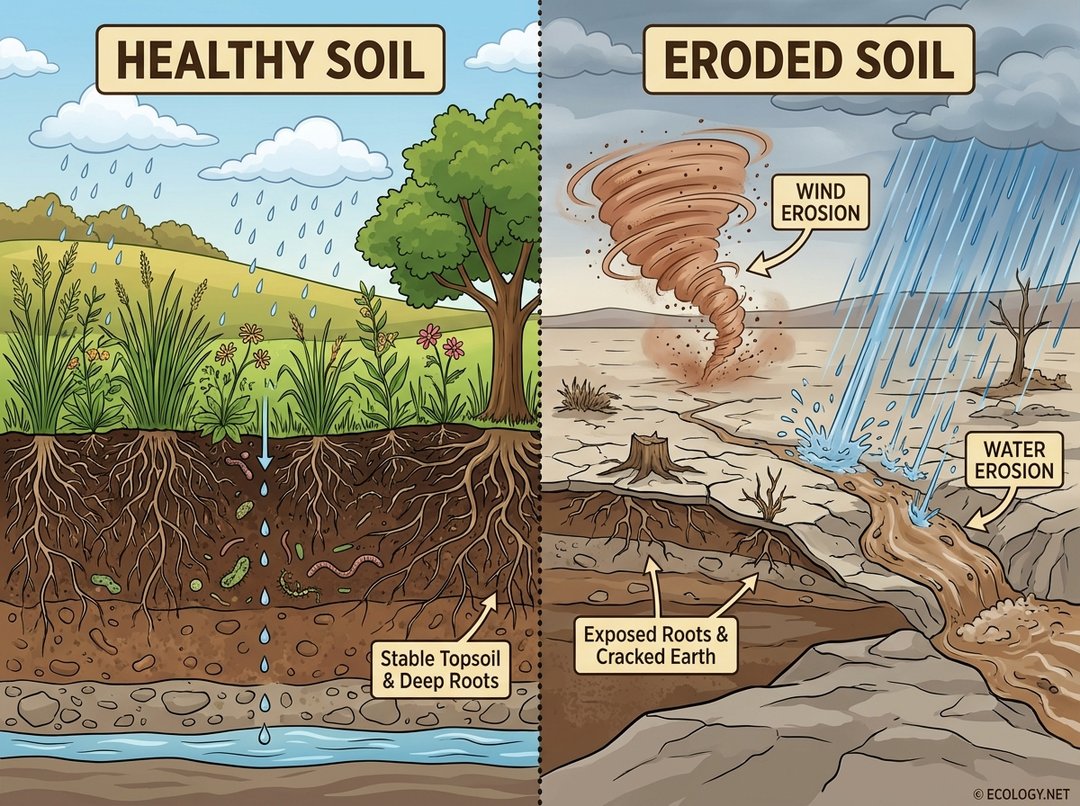

Erosion is the process by which topsoil, the most fertile layer, is detached and transported away by natural forces like wind and water. While a natural process, human activities have dramatically accelerated its pace, leading to devastating consequences.

The contrast between healthy and eroded soil is stark. Healthy soil, as depicted on the left, is characterized by a rich, dark color, stable structure, and a dense cover of vegetation with deep root systems that bind the soil together. This natural armor protects the soil from the elements.

In contrast, eroded soil, shown on the right, is often barren, cracked, and lighter in color, indicating a loss of organic matter. The protective vegetation is gone, leaving the soil vulnerable to:

- Wind Erosion: In dry, exposed areas, strong winds can lift and carry away vast quantities of fine topsoil particles, sometimes over great distances. Historical events like the American Dust Bowl of the 1930s serve as a grim reminder of wind erosion’s destructive power.

- Water Erosion: Heavy rainfall on bare or poorly managed land can lead to sheet erosion (uniform removal of a thin layer), rill erosion (small channels), and gully erosion (large, deep channels). This runoff not only removes precious topsoil but also carries sediments and pollutants into waterways, impacting aquatic ecosystems.

When topsoil is lost, so too are its vital nutrients, organic matter, and water-holding capacity, rendering the land less productive and often infertile.

Beyond Erosion: Other Pressures

While erosion is a primary concern, several other threats silently undermine soil health:

- Soil Compaction: Heavy machinery, livestock, and even foot traffic can compress soil particles, reducing pore space. This makes it harder for roots to penetrate, restricts water infiltration, and reduces air circulation, suffocating soil organisms.

- Nutrient Depletion: Intensive farming practices that continuously remove crops without replenishing nutrients can exhaust the soil’s fertility, leading to a reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

- Salinization: In arid and semi-arid regions, improper irrigation can lead to the accumulation of salts in the topsoil, making it toxic to most plants.

- Pollution: Industrial waste, pesticides, herbicides, and improper waste disposal can contaminate soil, rendering it unsuitable for agriculture and posing risks to human and ecosystem health.

- Loss of Organic Matter: Practices like excessive tillage and removal of crop residues reduce the organic content of soil, diminishing its ability to hold water, nutrients, and support microbial life.

The Imperative of Conservation: Why We Cannot Afford to Lose Our Soil

The threats to our soil are not isolated problems; they are interconnected challenges with far-reaching consequences. Soil conservation is not merely an environmental ideal; it is an economic necessity, a climate solution, and a cornerstone of global food security.

The health of our soil is inextricably linked to the health of our planet and its inhabitants. Protecting it is an investment in our collective future.

Without concerted efforts to conserve soil, we face:

- Reduced Food Production: Less fertile land means lower crop yields, threatening food supplies for a growing global population.

- Water Scarcity and Pollution: Eroded soil cannot absorb water effectively, leading to increased runoff, reduced groundwater recharge, and sedimentation of rivers and reservoirs. Pollutants carried by runoff further degrade water quality.

- Accelerated Climate Change: When soil organic matter is lost, the carbon stored within it is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

- Loss of Biodiversity: Soil degradation destroys the habitat for countless organisms, from microscopic bacteria to burrowing mammals, disrupting vital ecological processes.

- Desertification: Severe and prolonged soil degradation can lead to the transformation of fertile land into desert-like conditions, rendering it unproductive.

Guardians of the Earth: Effective Soil Conservation Techniques

Fortunately, humanity has developed and refined numerous techniques to protect and restore soil health. These methods often mimic natural processes, working with the land rather than against it.

Contour Farming and Terracing

These techniques are particularly effective on sloping land, where gravity and water runoff pose significant erosion risks.

- Contour Farming: Instead of plowing up and down a slope, farmers plant crops in rows that follow the natural contours of the land. These contour lines act as mini-dams, slowing down water flow, allowing it to infiltrate the soil rather than running off and carrying away topsoil. This simple change can reduce soil erosion by up to 50% on moderate slopes.

- Terracing: For steeper slopes, terracing involves constructing a series of level or nearly level platforms, or steps, along the contours of the hill. Each terrace has a raised edge or retaining wall to hold water and soil.

As seen in the image, ancient civilizations perfected terracing, creating sustainable agricultural systems that have endured for centuries. Modern terracing continues this legacy, transforming challenging landscapes into productive, erosion-resistant farmland.

No-Till and Minimum Tillage Farming

Traditional plowing, while preparing a seedbed, also exposes soil to the elements, breaks down soil structure, and releases carbon. No-till farming, also known as zero tillage, involves planting crops directly into the residue of the previous crop without disturbing the soil.

- Benefits: This practice significantly reduces soil erosion, improves water infiltration, increases soil organic matter, sequesters carbon, and reduces fuel consumption for machinery. Minimum tillage uses less aggressive soil disturbance than conventional plowing, offering similar but less pronounced benefits.

The Power of Cover Crops

Cover crops are plants grown primarily to protect and enrich the soil rather than for harvest. They are typically planted after the main crop is harvested or during fallow periods.

- Examples: Legumes like clover and vetch, grasses like rye and oats, and brassicas like radish.

- Benefits: Cover crops provide a living root system that holds soil in place, preventing erosion. They add organic matter when tilled under or left to decompose, suppress weeds, improve soil structure, and some legumes can even fix atmospheric nitrogen, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

Strategic Crop Rotation

Instead of planting the same crop in the same field year after year, crop rotation involves growing different types of crops in sequence on the same land.

- Benefits: This practice helps to break pest and disease cycles, improves soil fertility by alternating nutrient-demanding crops with nutrient-replenishing ones (like legumes), and enhances soil structure by varying root depths and types.

Agroforestry and Windbreaks

Integrating trees and shrubs into agricultural landscapes offers multiple benefits for soil conservation.

- Agroforestry: This system combines trees, crops, and/or livestock on the same land. Trees provide shade, reduce wind speed, improve soil organic matter through leaf litter, and their deep roots can access nutrients unavailable to shallow-rooted crops.

- Windbreaks: Rows of trees or shrubs planted strategically around fields act as barriers against wind erosion, protecting crops and topsoil from being blown away. They also create microclimates that can benefit crop growth.

Smart Grazing Management

Poor grazing practices, such as overgrazing, can lead to soil compaction and erosion. Sustainable grazing management involves rotating livestock through different pastures, allowing vegetation to recover.

- Benefits: This prevents overgrazing, promotes healthy grass growth with strong root systems, distributes manure more evenly (adding organic matter), and reduces soil compaction.

Riparian Buffer Zones

Riparian zones are the areas of land directly adjacent to rivers, streams, and other water bodies. Establishing or maintaining vegetated buffer zones in these areas is crucial.

- Benefits: These strips of trees, shrubs, and grasses filter runoff from agricultural fields, trapping sediments and pollutants before they enter waterways. They stabilize stream banks, preventing erosion, and provide essential habitat for wildlife.

A Holistic View: The Far-Reaching Benefits of Soil Conservation

The impact of soil conservation extends far beyond the boundaries of a single farm or field. It is a practice that yields profound benefits across environmental, economic, and social spheres, creating a more resilient and sustainable world.

Environmental Resilience

- Biodiversity Protection: Healthy soils are teeming with life, from microorganisms to insects and small mammals. Conservation practices protect these vital ecosystems, which are essential for nutrient cycling, pest control, and overall ecological balance.

- Water Quality Improvement: By reducing erosion and runoff, soil conservation prevents sediments, excess nutrients, and pesticides from polluting rivers, lakes, and oceans, safeguarding aquatic life and human drinking water supplies.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Increasing soil organic matter through practices like no-till and cover cropping enhances the soil’s capacity to sequester atmospheric carbon dioxide, acting as a natural carbon sink and helping to combat global warming.

- Enhanced Water Availability: Improved soil structure and organic matter content increase the soil’s ability to absorb and retain water, reducing drought susceptibility and recharging groundwater reserves.

Economic Stability

- Increased Crop Yields and Quality: Healthy, fertile soil supports more robust plant growth, leading to higher and more consistent crop yields and improved nutritional quality.

- Reduced Input Costs: Practices that build soil health can decrease the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, lowering operational costs for farmers.

- Long-Term Productivity: Conserving soil ensures the long-term productivity of agricultural land, protecting farmers’ livelihoods and the economic viability of rural communities.

- Reduced Disaster Risk: Healthy soils are more resilient to extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall and droughts, reducing the economic losses associated with natural disasters.

Social Well-being

- Food Security: By maintaining and enhancing the productivity of agricultural land, soil conservation directly contributes to global food security, ensuring stable and sufficient food supplies for all.

- Community Resilience: Sustainable land management practices foster more resilient communities, less vulnerable to environmental shocks and economic downturns.

- Improved Public Health: Cleaner water and healthier food systems, direct outcomes of soil conservation, contribute to better public health outcomes.

- Cultural Preservation: For many communities, especially indigenous populations, land stewardship and agricultural practices are deeply intertwined with cultural identity and heritage. Soil conservation helps preserve these vital connections.

Cultivating a Sustainable Future: What You Can Do

Soil conservation is not solely the responsibility of farmers or policymakers. Everyone has a role to play in protecting this invaluable resource.

- For Farmers and Land Managers:

- Implement no-till or minimum tillage practices.

- Plant cover crops during fallow periods.

- Rotate crops to improve soil health and break pest cycles.

- Establish contour farming or terraces on sloping land.

- Manage grazing livestock to prevent overgrazing and compaction.

- Plant windbreaks and integrate trees into farming systems (agroforestry).

- Create and maintain riparian buffer zones along waterways.

- For Gardeners and Homeowners:

- Compost kitchen and yard waste to create nutrient-rich organic matter for your garden.

- Use mulch around plants to retain moisture, suppress weeds, and add organic matter as it decomposes.

- Avoid over-tilling your garden soil.

- Plant diverse species, including native plants, to support soil biodiversity.

- Minimize the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

- Install rain barrels or create rain gardens to manage stormwater runoff.

- For Consumers and Citizens:

- Support farmers who practice sustainable and regenerative agriculture. Look for certifications or ask about their methods.

- Educate yourself and others about the importance of soil health.

- Advocate for policies that promote soil conservation and sustainable land use.

- Reduce food waste, as wasted food represents wasted soil resources.

Conclusion: A Foundation for Life

Soil conservation is more than just a set of agricultural practices; it is a philosophy of stewardship, a recognition of our profound dependence on the natural world. From the food on our plates to the air we breathe and the water we drink, healthy soil underpins the very fabric of life.

The challenges to soil health are significant, but the solutions are within reach. By understanding the vital functions of soil, recognizing the threats it faces, and actively implementing conservation techniques, we can safeguard this precious resource for current and future generations. Investing in soil conservation is investing in a sustainable, resilient, and thriving planet for all.