In the intricate web of life, every creature plays a vital role, from the towering predators to the microscopic decomposers. Yet, there is a group of organisms often overlooked, sometimes even maligned, that performs one of the most essential services in any ecosystem: the scavengers. These natural recyclers are the unsung heroes of environmental health, diligently cleaning up what others leave behind and ensuring the continuous flow of nutrients that sustains all life.

Imagine a world without scavengers. Carcasses would litter landscapes, becoming breeding grounds for disease and locking away valuable nutrients. The air would be thick with the stench of decay, and ecosystems would grind to a halt. Fortunately, nature has equipped itself with a diverse and efficient clean-up crew, working tirelessly to maintain balance and vitality. Understanding scavengers is not just about appreciating their unique adaptations; it is about recognizing a fundamental pillar of ecological stability.

What Exactly is a Scavenger? Nature’s Essential Recyclers

At its core, a scavenger is an animal that feeds on carrion, dead plant material, or waste products that it did not kill itself. This distinguishes them from predators, who actively hunt and kill their prey, and from decomposers like bacteria and fungi, which break down organic matter at a microbial level. Scavengers bridge the gap between death and decomposition, accelerating the process of nutrient return to the environment.

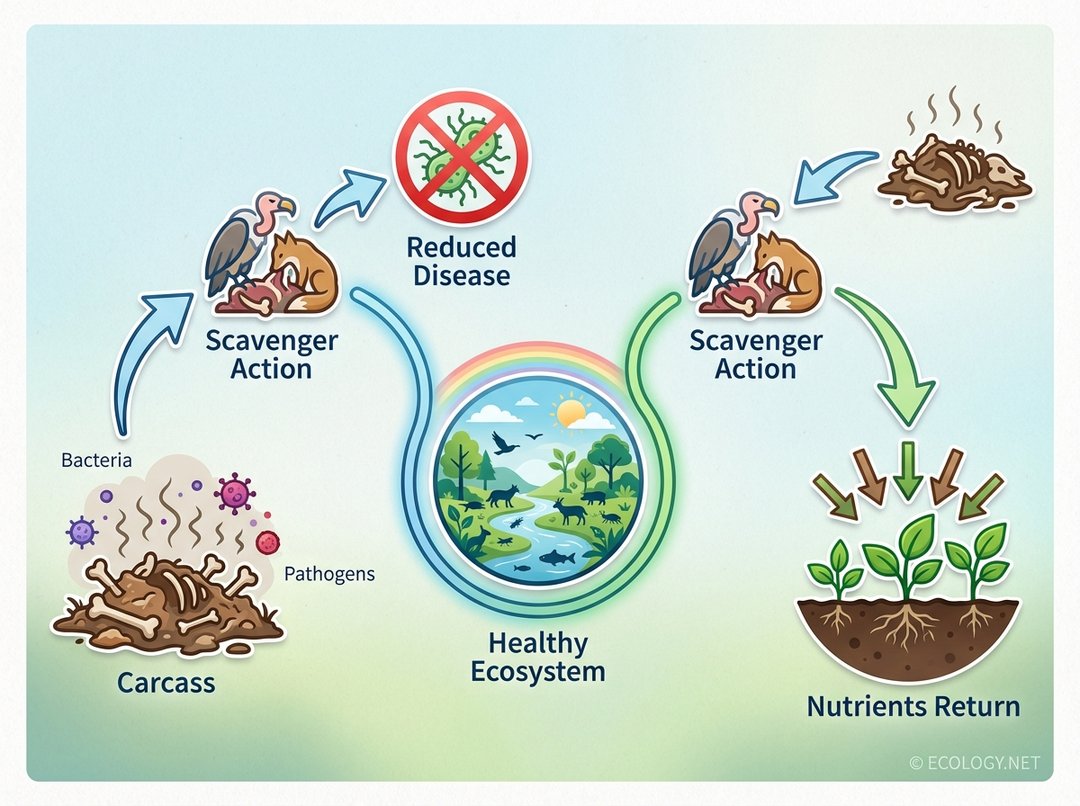

Their role is far more sophisticated than simply “eating dead things.” By consuming deceased organisms, scavengers prevent the build-up of decaying matter, which can harbor pathogens and disrupt the delicate balance of an ecosystem. They are the first responders to death, ensuring that energy and nutrients are not wasted but are instead cycled back into the food web, supporting new life.

Beyond Vultures: A Wider Range of Scavengers

When most people think of scavengers, the image of a vulture circling overhead often comes to mind. While vultures are indeed iconic scavengers, the diversity of creatures that engage in scavenging is astonishingly vast, spanning nearly every corner of the planet and every branch of the animal kingdom. From the largest mammals to the smallest insects, many species contribute to this vital ecological service.

Mammalian Scavengers

- Hyenas: Particularly the spotted hyena, are highly efficient scavengers, known for their powerful jaws that can crush bones, extracting every last bit of nutrition from a carcass.

- Coyotes and Jackals: These canids are opportunistic, often scavenging on roadkill or the remains left by larger predators.

- Bears: Many bear species, including grizzly bears and black bears, will readily consume carrion, especially during lean times or when easy meals are available.

- Raccoons and Opossums: Common in urban and suburban areas, these adaptable animals are notorious for rummaging through human waste and consuming roadkill.

Avian Scavengers

- Vultures: Both Old World (e.g., Griffon Vulture, Lappet-faced Vulture) and New World (e.g., Turkey Vulture, California Condor) vultures are obligate scavengers, perfectly adapted with keen eyesight, powerful beaks, and often featherless heads for hygiene.

- Eagles and Kites: While primarily predators, many raptors will not pass up an easy meal of carrion.

- Crows and Ravens: Highly intelligent and adaptable, these birds are common scavengers, especially in human-modified landscapes.

Insect Scavengers

Perhaps the most numerous and often overlooked scavengers are insects, which play a critical role in breaking down carcasses and other organic matter.

- Carrion Beetles (Sexton Beetles): These fascinating insects bury small carcasses, laying their eggs on them and providing a protected food source for their larvae.

- Maggots (Fly Larvae): The larvae of various fly species are incredibly efficient at consuming soft tissues of decaying animals, rapidly reducing a carcass to bones.

- Ants and Wasps: Many species will feed on dead insects or small pieces of carrion.

Aquatic Scavengers

The underwater world also has its dedicated clean-up crew.

- Crabs and Lobsters: Many species of crustaceans, both marine and freshwater, are opportunistic scavengers, feeding on dead fish, plants, and other detritus.

- Catfish: Bottom-dwelling fish like catfish often scavenge for dead organisms and decaying plant matter on the riverbed or lakebed.

- Hagfish: These ancient, eel-like creatures are renowned for their ability to enter carcasses through orifices and consume them from the inside out.

- Sharks: While formidable predators, many shark species, such as tiger sharks, are also opportunistic scavengers, feeding on dead whales or other marine animals.

The Ecological Importance of Scavengers

The work of scavengers extends far beyond simply tidying up. Their activities are fundamental to the health and functioning of ecosystems, providing a suite of benefits that are often taken for granted.

Disease Control and Prevention

One of the most critical roles of scavengers is preventing the spread of disease. Decaying carcasses are prime breeding grounds for bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens that can infect living animals, including humans. By rapidly consuming these carcasses, scavengers effectively remove potential sources of infection from the environment.

- Vultures: Their highly acidic stomach acids are capable of neutralizing dangerous bacteria like anthrax, cholera, and botulism, which would otherwise thrive in decaying flesh. This makes them incredibly important biological incinerators.

- Insects: Maggots, for instance, can consume a carcass in a matter of days, preventing the prolonged exposure of pathogens to the environment.

Nutrient Cycling and Energy Flow

Scavengers are crucial links in the nutrient cycle. When an animal dies, its body contains a wealth of organic matter and essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon. Without scavengers, these nutrients would be locked up in carcasses for much longer, slowing their return to the soil and plants.

- By consuming carrion, scavengers break down complex organic molecules into simpler forms.

- Their waste products and eventual decomposition release these nutrients back into the soil, making them available for plants to absorb.

- This continuous cycling ensures that ecosystems remain productive and fertile, supporting the growth of vegetation that forms the base of the food web.

Maintaining Ecosystem Balance

Scavengers contribute to overall ecosystem stability by regulating populations and providing food for other organisms. They prevent the accumulation of dead biomass, which could otherwise overwhelm an environment. In some cases, they also provide food for other scavengers or decomposers, creating a complex network of interactions.

Types of Scavenging: A Deeper Dive

The world of scavenging is not monolithic; different species exhibit varying degrees of reliance on carrion, leading to classifications that help ecologists understand their specific roles.

Obligate vs. Facultative Scavengers

- Obligate Scavengers: These animals rely almost exclusively on carrion for their diet. Vultures are the quintessential example, possessing specialized adaptations for finding and consuming dead animals. Their survival is directly tied to the availability of carcasses.

- Facultative Scavengers: These are opportunistic feeders that will consume carrion when available, but also hunt live prey or forage for plant matter. Many predators, like hyenas, coyotes, and even lions, fall into this category. They are adaptable and can switch between hunting and scavenging depending on circumstances.

Vertebrate vs. Invertebrate Scavengers

- Vertebrate Scavengers: This group includes mammals (hyenas, bears, raccoons), birds (vultures, crows), and some fish (catfish, sharks). They are often the first to arrive at a large carcass and can consume significant portions.

- Invertebrate Scavengers: Insects (beetles, maggots, ants) and crustaceans (crabs, lobsters) are vital invertebrate scavengers. They often specialize in breaking down smaller carcasses or the remaining tissues after larger scavengers have fed. Their sheer numbers and rapid reproduction rates make them incredibly efficient.

Terrestrial vs. Aquatic Scavengers

- Terrestrial Scavengers: These operate on land, including most of the examples discussed above, from vultures in the sky to beetles on the ground.

- Aquatic Scavengers: Found in freshwater and marine environments, these include a variety of fish, crustaceans, and other invertebrates that clean up dead organisms and detritus from the water column and seafloor.

Scavengers in Different Ecosystems

The specific types of scavengers and their impact vary significantly across different biomes, each presenting unique challenges and opportunities for these vital organisms.

Grasslands and Savannas

These open environments, home to large herds of herbivores and powerful predators, are classic scavenging hotspots. Vultures dominate the skies, quickly locating carcasses, while hyenas and jackals patrol the ground, efficiently processing remains. The rapid consumption of carcasses here is crucial for preventing disease outbreaks among dense animal populations.

Forests

Forest ecosystems, with their dense canopy and often cooler, moister conditions, support a different suite of scavengers. Insects, particularly various species of beetles and fly larvae, are paramount in breaking down smaller carcasses and even larger ones in stages. Mammals like raccoons, opossums, and even bears are important facultative scavengers, especially in temperate and boreal forests.

Marine Environments

The vastness of the ocean means that dead organisms, from small fish to massive whales, can sink to the seafloor. Here, a specialized community of deep-sea scavengers, including hagfish, various crustaceans, and even some sharks, plays a critical role in processing these “whale falls” and other organic matter, ensuring nutrients are recycled even in the deepest trenches.

Urban and Suburban Landscapes

Human settlements create their own unique scavenging niches. Animals like crows, gulls, raccoons, opossums, and rats thrive by consuming human waste, roadkill, and discarded food. While sometimes considered pests, these urban scavengers perform an ecological service by cleaning up anthropogenic refuse, albeit often in ways that bring them into conflict with humans.

Threats to Scavenger Populations

Despite their indispensable role, scavenger populations worldwide face significant threats, often due to human activities. The decline of these species can have cascading negative effects on entire ecosystems.

Poisoning

One of the most devastating threats to scavengers, particularly vultures and large mammals, is poisoning. This can occur intentionally, when carcasses are laced with poison to target predators like wolves or hyenas, but scavengers become unintended victims. Accidental poisoning also happens through veterinary drugs, such as diclofenac, which caused catastrophic declines in vulture populations across South Asia.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

As human populations expand, natural habitats are converted for agriculture, development, and infrastructure. This reduces the availability of wild prey and carrion, and fragments the remaining habitats, making it harder for scavengers to find food and safe nesting or denning sites.

Reduced Food Availability

Changes in wildlife populations, often due to hunting, disease, or habitat loss, can lead to a reduction in the number of carcasses available for scavengers. For obligate scavengers, this can be a direct threat to their survival.

Human Conflict

In some regions, scavengers are persecuted due to misconceptions or perceived threats to livestock. For example, hyenas are sometimes killed by farmers who mistakenly believe they are solely responsible for livestock predation, when in reality they often scavenge on animals that have already died or been killed by other predators.

The Future of Scavengers: Conservation Efforts

Recognizing the critical importance of scavengers, conservation efforts are underway globally to protect these vital species and the services they provide.

- Anti-Poisoning Campaigns: Educating communities about the dangers of poison and promoting alternative methods of predator control are crucial. In South Asia, bans on veterinary diclofenac have shown promising signs of vulture recovery.

- Habitat Protection: Establishing protected areas and wildlife corridors helps ensure scavengers have access to sufficient food resources and safe breeding grounds.

- Reintroduction Programs: For critically endangered species like the California Condor, captive breeding and reintroduction programs are vital to boost wild populations.

- Public Awareness: Changing public perception of scavengers from “gross” or “dangerous” to “essential” is key. Education can highlight their ecological benefits and foster appreciation.

- Monitoring and Research: Continuous monitoring of scavenger populations and research into their ecology helps inform effective conservation strategies.

Conclusion

Scavengers, in all their diverse forms, are indispensable architects of healthy ecosystems. They are the clean-up crew, the disease preventers, and the nutrient recyclers, working tirelessly to ensure that life’s cycle continues unbroken. From the majestic flight of a vulture to the unseen work of a carrion beetle, their contributions are profound and far-reaching.

By understanding and appreciating the vital roles these creatures play, humanity can better protect them and, in doing so, safeguard the health and resilience of the natural world. The next time you see a scavenger at work, remember that you are witnessing one of nature’s most efficient and essential processes, a testament to the intricate balance that sustains all life on Earth.