Life on Earth, in all its intricate forms, relies on a delicate balance of elements. While carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen often steal the spotlight, there is a quieter, yet equally fundamental player: phosphorus. This essential element underpins the very fabric of biological existence, from the energy currency within our cells to the genetic blueprint that defines us. Unlike its atmospheric counterparts, phosphorus embarks on a unique journey, primarily cycling through rocks, soil, water, and living organisms in what scientists call the phosphorus cycle. Understanding this cycle is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for comprehending the health of our planet and the sustainability of life itself.

What is the Phosphorus Cycle?

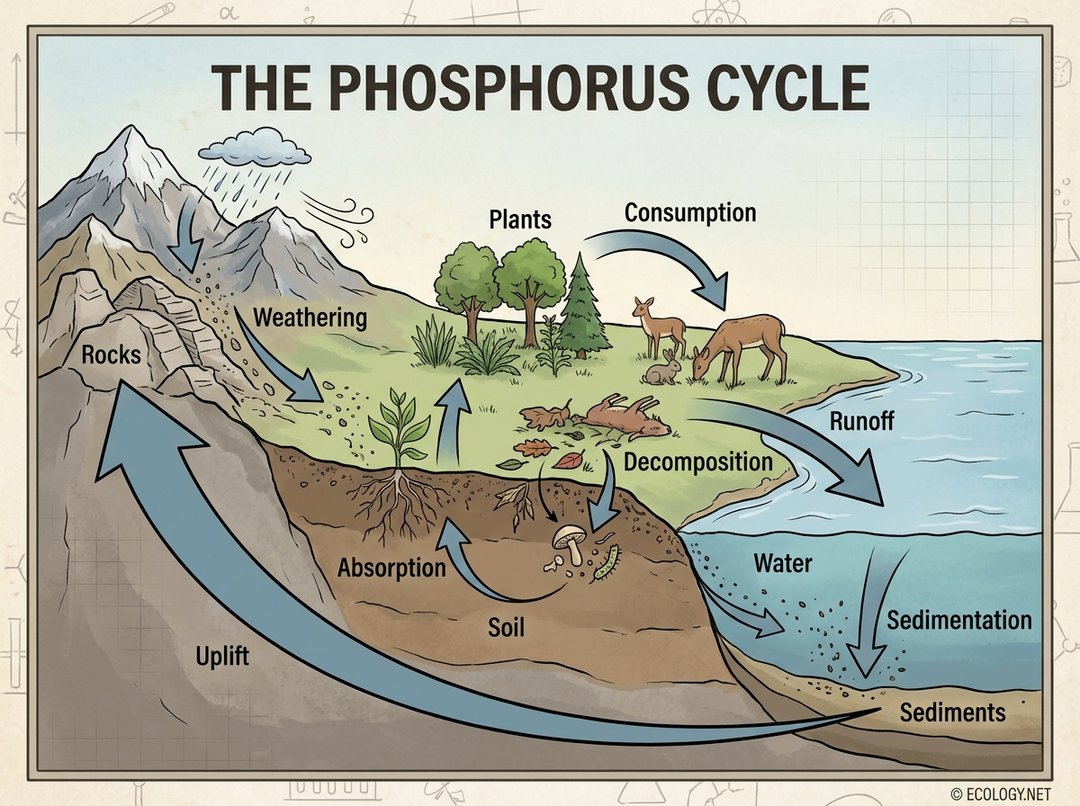

The phosphorus cycle describes the biogeochemical movement of phosphorus through the Earth’s lithosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere. It is distinct from cycles like the carbon or nitrogen cycle because phosphorus does not have a significant gaseous phase. Instead, its primary reservoir is in rocks and sediments, making it a slow, sedimentary cycle. This means that the availability of phosphorus can often be a limiting factor for growth in many ecosystems, both on land and in water.

Imagine phosphorus as a vital nutrient that takes a long, winding path. It begins locked away in ancient rocks, slowly released over millennia, before embarking on a journey through the soil, into plants, up the food chain, and eventually back to the earth or into aquatic environments. This continuous, albeit gradual, movement ensures that life has access to this indispensable element.

Why is Phosphorus Important?

Before delving into the mechanics of its cycle, it is essential to appreciate why phosphorus holds such a critical position in biology. Its roles are fundamental and pervasive:

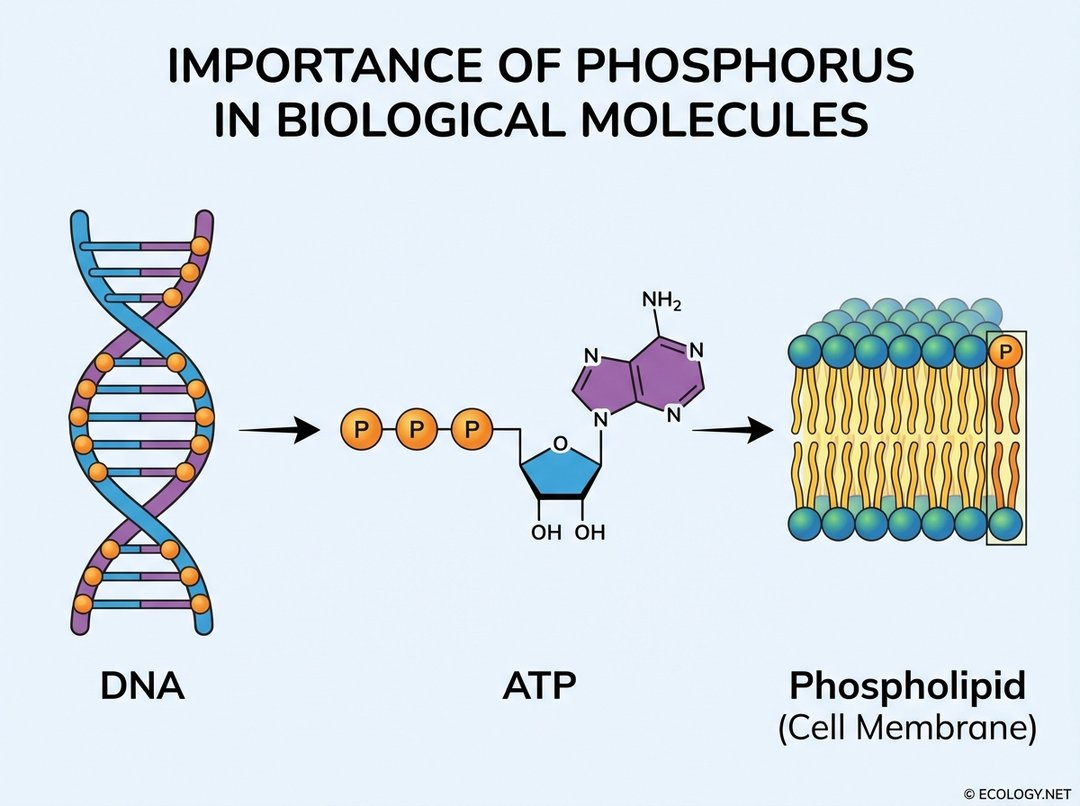

- Genetic Material: Phosphorus is a cornerstone of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), the molecules that carry genetic information in all living organisms. The sugar-phosphate backbone of these nucleic acids provides their structural integrity.

- Energy Transfer: Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is often called the “energy currency” of the cell. Phosphorus, in the form of phosphate groups, is central to ATP’s structure. The breaking and forming of phosphate bonds in ATP release and store the energy needed for virtually all cellular processes, from muscle contraction to nerve impulses.

- Cell Membranes: Phospholipids are the primary components of cell membranes, forming the vital barrier that encloses cells and regulates the passage of substances. These molecules have a hydrophilic (water-loving) phosphate head and hydrophobic (water-fearing) fatty acid tails, allowing them to spontaneously form bilayers in aqueous environments.

- Bone and Teeth Formation: In vertebrates, calcium phosphate is the main mineral component of bones and teeth, providing structural support and rigidity.

- Enzyme Activation: Phosphate groups are often added to proteins to activate or deactivate enzymes, playing a crucial role in regulating metabolic pathways.

Without phosphorus, life as we know it simply could not exist. It is a non-negotiable requirement for growth, reproduction, and the very functioning of cells.

The Stages of the Phosphorus Cycle

The phosphorus cycle can be broken down into several key stages, illustrating its journey through various environmental compartments:

1. Weathering

The cycle begins with the slow release of phosphorus from its primary geological reservoir: rocks. Over vast stretches of time, rain, wind, and other erosive forces break down phosphate-rich rocks, a process known as weathering. This releases inorganic phosphate ions (PO₄³⁻) into the soil and water.

Consider a mountain range slowly eroding over millions of years. Each raindrop and gust of wind chips away at the rock, gradually freeing the phosphorus compounds locked within.

2. Absorption by Plants

Once in the soil, inorganic phosphate is absorbed by plants through their roots. This is a critical step, as plants are the entry point for phosphorus into the biological food web. The availability of soluble phosphate in the soil is often limited, making it a key nutrient for plant growth.

3. Consumption by Animals

Animals obtain phosphorus by consuming plants or other animals that have eaten plants. For instance, a deer eats grass, acquiring the phosphorus stored in the plant tissues. A wolf then eats the deer, incorporating that phosphorus into its own body.

4. Decomposition

When plants and animals die, decomposers such as bacteria and fungi break down their organic matter. During this process, known as decomposition, the organic phosphorus compounds are converted back into inorganic phosphate, which is then released into the soil or water, making it available for plants once again. This completes the biological loop of the cycle.

5. Runoff and Sedimentation

Phosphorus can be transported from terrestrial to aquatic ecosystems through runoff. Rainwater carries phosphate-rich soil particles and dissolved phosphates from land into rivers, lakes, and oceans. In these water bodies, some phosphorus is taken up by aquatic plants and algae. However, a significant portion settles to the bottom as sediment, forming new phosphate-rich rocks over geological timescales. This process, called sedimentation, effectively removes phosphorus from active circulation for potentially millions of years.

6. Uplift

Over immense geological periods, the Earth’s tectonic forces can cause the uplift of these phosphorus-rich sediments, bringing them back to the surface as new rock formations. This completes the very long-term geological part of the cycle, making the phosphorus available for weathering once more.

Human Impact on the Phosphorus Cycle

While the natural phosphorus cycle is a slow and balanced process, human activities have significantly altered its pace and distribution, leading to both benefits and severe environmental consequences.

Agriculture and Fertilizers

One of the most profound human impacts comes from agriculture. To boost crop yields, farmers apply phosphorus-rich fertilizers to their fields. While essential for food production, a substantial portion of this applied phosphorus is not absorbed by crops. Instead, it can leach into groundwater or be carried by runoff into nearby aquatic ecosystems.

Wastewater and Detergents

Historically, phosphorus compounds were widely used in detergents to enhance cleaning power. Although many regions have now banned or restricted their use, wastewater from homes and industries still contains significant amounts of phosphorus from human waste and other sources. Untreated or inadequately treated wastewater discharges contribute to phosphorus loading in aquatic environments.

Mining

To produce fertilizers and other phosphorus-containing products, humans mine phosphate rock. This extraction process depletes finite geological reserves and can cause significant environmental disruption at mining sites, including habitat destruction and water pollution.

Eutrophication: A Major Concern

Perhaps the most visible and damaging consequence of human disruption to the phosphorus cycle is eutrophication. This phenomenon occurs when excessive amounts of nutrients, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, enter aquatic ecosystems. The influx of phosphorus acts as a powerful fertilizer for algae and aquatic plants, leading to rapid and uncontrolled growth known as an “algae bloom.”

These dense blooms block sunlight from reaching submerged vegetation, causing it to die. As the algae themselves eventually die, decomposers consume them, a process that rapidly depletes oxygen from the water. This creates “dead zones” where fish and other aquatic organisms cannot survive, leading to widespread mortality and a drastic reduction in biodiversity. Lakes, rivers, and coastal areas around the world suffer from the devastating effects of eutrophication, a direct result of too much phosphorus entering these sensitive environments.

Consequences of Imbalance

The imbalance in the phosphorus cycle has far-reaching consequences beyond eutrophication. It affects global food security, as the availability of phosphate rock is finite and concentrated in a few countries. Mismanagement of phosphorus can also lead to soil degradation and reduced agricultural productivity in the long term. Furthermore, the energy-intensive processes of mining and producing phosphorus fertilizers contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Conclusion

The phosphorus cycle, though often overlooked, is a cornerstone of life on Earth. From the microscopic world of cellular energy to the vast geological forces that shape our planet, phosphorus plays an indispensable role. While human ingenuity has harnessed this element to feed a growing global population, our interventions have also created significant ecological challenges. Understanding the intricacies of the phosphorus cycle empowers us to develop more sustainable agricultural practices, improve wastewater treatment, and manage this vital resource more responsibly. By respecting the natural rhythms of this essential cycle, humanity can work towards a future where both ecological health and human prosperity can thrive.