Understanding Native Species: The Foundation of Healthy Ecosystems

Every landscape, from the densest rainforest to the driest desert, is a tapestry woven with life. At the heart of this intricate web are native species, organisms that have evolved and thrived in a particular region for millennia. Their presence is not a matter of chance but the result of a long, natural journey, shaping the very character of an ecosystem. Understanding what makes a species native is fundamental to appreciating biodiversity, recognizing ecological health, and guiding effective conservation efforts.

What Exactly Defines a Native Species?

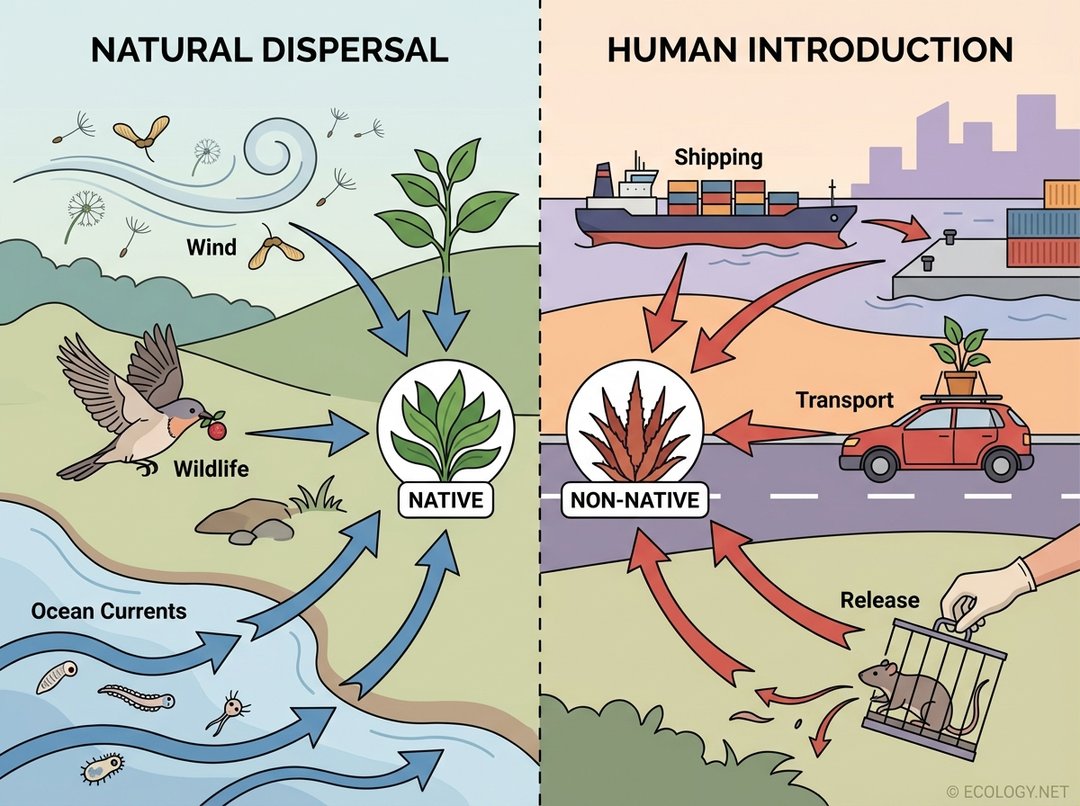

A native species, sometimes referred to as an indigenous species, is an organism that occurs naturally in a particular region, ecosystem, or habitat without direct or indirect human intervention. This means its presence is due to natural processes of dispersal and evolution over geological time. Think of a saguaro cactus in the Sonoran Desert, a kangaroo in Australia, or a polar bear in the Arctic. These species arrived in their respective homes through natural means, such as wind carrying seeds, ocean currents transporting marine life, or animals migrating across land bridges.

The crucial distinction lies in how a species arrives. While native species arrive through natural dispersal mechanisms, non-native species are introduced to new environments, either intentionally or unintentionally, by human activity. This human-mediated introduction bypasses the natural barriers and dispersal limitations that would otherwise prevent a species from reaching a new area.

Unpacking the Terminology: Native, Indigenous, and Endemic

The terms “native,” “indigenous,” and “endemic” are often used interchangeably, but they carry distinct ecological meanings. While closely related, understanding their nuances is key to precise ecological discourse.

- Native: This is the broadest term, referring to any species that naturally occurs in a given area without human introduction. It implies a natural presence, regardless of whether it originated there or dispersed from elsewhere.

- Indigenous: Often used synonymously with native, “indigenous” specifically emphasizes that a species originated in a particular geographic region. While all indigenous species are native, not all native species are indigenous to the exact spot they are found if they dispersed there from a nearby region. For example, a species might be indigenous to a continent but merely native to a specific country within that continent, having dispersed there naturally.

- Endemic: This term describes a species that is native and *exclusive* to a specific geographic area. An endemic species is found nowhere else on Earth. This often applies to species on islands, in isolated mountain ranges, or within unique ecosystems. For instance, the lemurs of Madagascar are endemic to that island, and the Galapagos tortoises are endemic to the Galapagos Islands. Endemism highlights a species’ unique evolutionary history and its vulnerability to habitat loss within its restricted range.

This diagram helps visualize these relationships: a species can be native to a large region, indigenous to a smaller area within it where it originated, and endemic if its entire global range is confined to a very specific, often isolated, location.

Why Do Native Species Matter? The Pillars of Ecological Health

The significance of native species extends far beyond their mere presence. They are the fundamental building blocks of healthy, resilient ecosystems, playing irreplaceable roles that have evolved over millennia.

Ecological Balance and Food Webs

Native species are intricately woven into the food webs of their ecosystems. They have co-evolved with other native plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms, forming complex relationships of predator and prey, herbivore and plant, parasite and host. Each species occupies a specific niche, contributing to the flow of energy and nutrients. When a native species is lost, or its population declines, it can create ripple effects throughout the food web, impacting many other species that depend on it for food, shelter, or other ecological services.

Ecosystem Services

Native plants, in particular, are crucial providers of essential ecosystem services. They stabilize soil, prevent erosion, filter water, cycle nutrients, and contribute to local climate regulation. Native pollinators, such as bees, butterflies, and bats, are vital for the reproduction of many native plants, including those that produce food for humans. Native trees and shrubs provide critical habitat and food sources for native wildlife, supporting entire communities of insects, birds, and mammals.

Genetic Diversity and Resilience

Native populations often possess a high degree of genetic diversity, which is the raw material for adaptation to changing environmental conditions. This genetic richness allows species to evolve and cope with new diseases, pests, or climate shifts. Ecosystems dominated by native species tend to be more resilient and better able to recover from disturbances, whether natural events like wildfires or human-induced pressures.

Cultural and Aesthetic Value

Beyond their ecological importance, native species hold immense cultural and aesthetic value. They are often deeply intertwined with local traditions, folklore, and indigenous knowledge systems. Their unique beauty and presence contribute to the distinct character and sense of place of a region, inspiring art, literature, and a connection to nature for countless people.

Threats to Native Species: The Rise of the Non-Natives

Despite their resilience, native species face numerous threats, with habitat loss and the introduction of non-native species being among the most significant. When a non-native species establishes itself and causes harm to the environment, economy, or human health, it is classified as an invasive species. These invaders can wreak havoc on native ecosystems.

A classic example of this ecological disruption is the plight of the native red squirrel in the United Kingdom, which has been severely impacted by the introduction of the invasive gray squirrel from North America.

- Competition: Gray squirrels are larger, more adaptable, and can outcompete red squirrels for food resources, particularly nuts, and for nesting sites. They also carry a parapoxvirus that is lethal to red squirrels but harmless to themselves.

- Predation: Invasive predators can decimate native prey populations that have not evolved defenses against them. For instance, the brown tree snake introduced to Guam has driven many native bird species to extinction.

- Disease: As seen with the gray squirrel, invasive species can introduce novel diseases or parasites to which native species have no immunity, leading to widespread mortality.

- Habitat Alteration: Some invasive plants, like kudzu in the southeastern United States, can grow aggressively, smothering native vegetation and altering entire forest structures. Invasive animals can also change habitats, such as feral pigs rooting up native plant communities.

- Hybridization: In some cases, non-native species can interbreed with native species, leading to hybridization that dilutes the genetic integrity of the native population.

Identifying Native Species: A Local Detective Story

Determining whether a species is native to a particular area is a complex task that often requires a blend of historical research, scientific observation, and advanced analytical techniques. Ecologists and botanists act as detectives, piecing together clues from various sources.

- Historical Records: Old maps, explorer journals, early botanical surveys, and even local folklore can provide valuable insights into the historical distribution of species before significant human impact.

- Fossil and Paleobotanical Evidence: The discovery of fossilized remains, pollen grains, or ancient seeds in geological strata can confirm the long-term presence of a species in a region.

- Ecological Context: Observing how a species interacts with other organisms in an ecosystem can offer clues. Native species typically have established relationships with local pollinators, herbivores, and predators, whereas non-native species might lack these connections or disrupt existing ones.

- Genetic Analysis: DNA sequencing can reveal the evolutionary history and geographic origins of a species. By comparing genetic markers, scientists can trace ancestral lineages and determine if a population has been present in an area for a long evolutionary period.

- Biogeographical Patterns: Understanding global patterns of species distribution and dispersal helps identify whether a species’ presence in a particular area fits expected natural ranges or suggests an introduction.

Conservation Efforts: Protecting Our Natural Heritage

The protection of native species is a cornerstone of biodiversity conservation. Recognizing their intrinsic value and ecological importance drives numerous efforts worldwide.

- Habitat Restoration: Recreating or rehabilitating degraded habitats with native plant species is crucial. This provides food, shelter, and breeding grounds for native wildlife, helping to re-establish ecological balance.

- Invasive Species Management: Controlling and eradicating invasive species is a critical step in protecting native flora and fauna. This can involve manual removal, biological controls, or targeted chemical treatments, always with careful consideration for non-target species.

- Protected Areas: Establishing national parks, wildlife refuges, and other protected areas safeguards critical habitats and allows native species to thrive without human disturbance.

- Public Awareness and Education: Educating the public about the importance of native species and the dangers of invasive ones is vital. Simple actions, like planting native gardens or cleaning hiking boots to prevent seed dispersal, can make a significant difference.

- Policy and Legislation: Government policies and international agreements play a crucial role in regulating trade in potentially invasive species, funding conservation initiatives, and protecting endangered native species.

Conclusion: A Call to Value Our Natural World

Native species are more than just components of an ecosystem; they are the very essence of its identity and resilience. Their long evolutionary journey in a specific place has shaped the intricate relationships that sustain life, provide essential services, and enrich our world. By understanding, valuing, and actively protecting native species, we are not only preserving biodiversity but also ensuring the health and stability of the natural systems upon which all life, including our own, ultimately depends. Every effort to support native plants and animals contributes to a healthier, more vibrant planet for generations to come.