The ground beneath our feet often feels like an unyielding, static foundation, a silent stage upon which all life unfolds. Yet, this seemingly inert layer of Earth, known as the lithosphere, is anything but passive. It is a dynamic, ever-changing realm that not only supports life but actively shapes it, creating the diverse landscapes and intricate ecological systems we observe across our planet.

Understanding the lithosphere is fundamental to grasping how Earth functions as a living system. From the towering peaks of mountain ranges to the deepest ocean trenches, and from the fertile soils that feed us to the very air we breathe, the lithosphere plays an indispensable role in nearly every aspect of our world.

What Exactly is the Lithosphere? Defining Earth’s Solid Skin

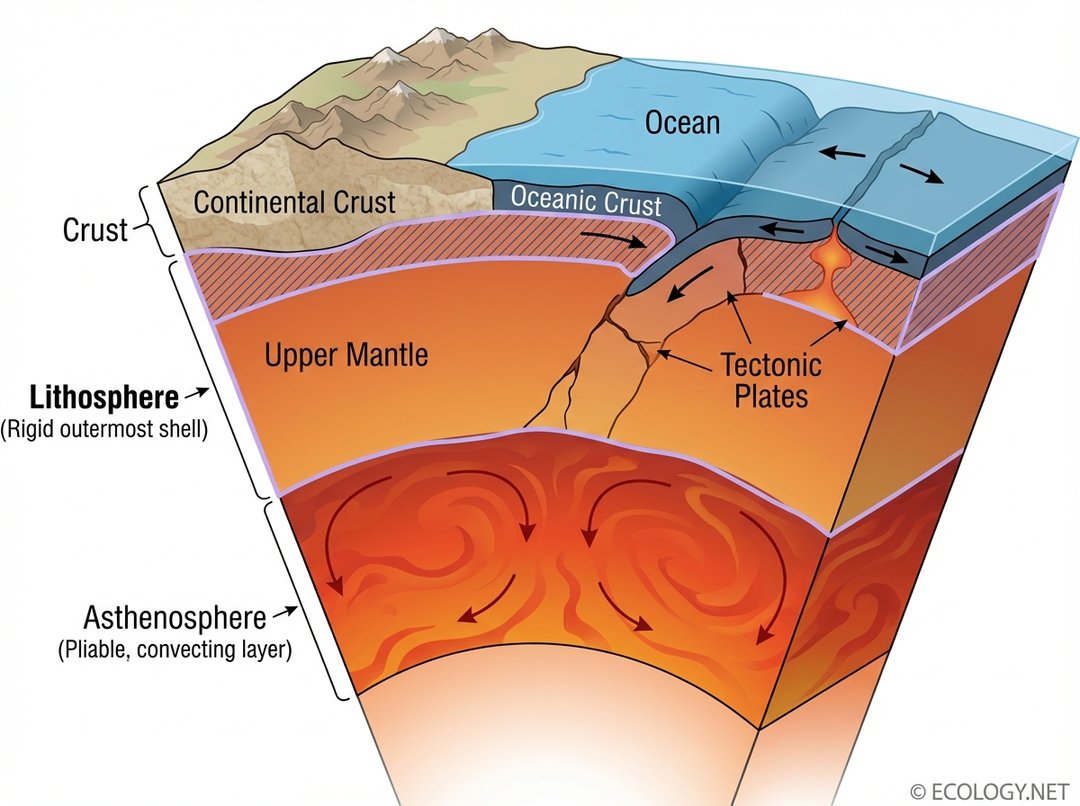

At its core, the lithosphere represents Earth’s rigid, outermost shell. Think of it as the planet’s tough, rocky skin. It is not a single, uniform layer but a composite structure comprising two distinct parts:

- The Crust: This is the very surface layer, the part we live on. It is surprisingly thin compared to the Earth’s overall size, much like the skin of an apple. The crust itself comes in two main varieties:

- Oceanic Crust: Thinner and denser, primarily composed of basalt, it forms the ocean floors.

- Continental Crust: Thicker and less dense, made mostly of granite, it forms the continents and continental shelves.

- The Uppermost Part of the Mantle: Directly beneath the crust lies the mantle, a much thicker layer of hot, dense rock. The very top portion of this mantle, which is solid and rigid, is fused with the crust to form the lithosphere.

This combined crust and rigid upper mantle floats atop a more pliable, semi-fluid layer called the asthenosphere. The asthenosphere’s ability to flow slowly allows the lithosphere above it to move. This movement is not uniform or continuous across the entire globe. Instead, the lithosphere is fractured into enormous, irregularly shaped pieces known as tectonic plates.

These tectonic plates are in constant, albeit slow, motion, grinding past each other, pulling apart, or colliding. This geological ballet is responsible for many of Earth’s most dramatic features and phenomena, including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the formation of mountain ranges.

The Lithosphere: Architect of Diverse Habitats

The dynamic nature of the lithosphere makes it a master architect of habitats. Its geological processes sculpt the Earth’s surface, creating an astonishing array of environments that support unique ecosystems and foster incredible biodiversity. Without the lithosphere’s constant reshaping, our planet would be a far less varied and biologically rich place.

Mountains: Elevating Biodiversity

When tectonic plates collide, the immense pressure can cause the Earth’s crust to buckle and fold, giving rise to majestic mountain ranges. These towering landforms create diverse microclimates across their slopes. From lush forests at their base to alpine meadows and barren, rocky peaks, mountains offer a gradient of conditions that support a wide variety of plant and animal life, often leading to high levels of endemism.

Rift Valleys: Cradles of Unique Evolution

Where tectonic plates pull apart, the lithosphere stretches and thins, often forming deep depressions known as rift valleys. These valleys can fill with water, creating unique lakes that become isolated evolutionary laboratories. The Great Rift Valley in East Africa, for instance, hosts a series of ancient lakes renowned for their exceptional biodiversity, particularly their endemic fish species that have evolved in isolation over millions of years.

Volcanic Islands: New Land, New Life

Volcanic activity, often occurring at plate boundaries or over hot spots, can bring molten rock from deep within the Earth to the surface. When this happens in the ocean, it can lead to the formation of new land in the form of volcanic islands. These islands, initially barren lava flows, undergo ecological succession, gradually being colonized by pioneer species, eventually developing into complex ecosystems. The Galapagos Islands are a prime example, where unique species have evolved in isolation on these geologically young landmasses.

Cave Systems: Stable, Isolated Worlds

Beneath the surface, the lithosphere also harbors vast and intricate cave systems. Formed by the dissolution of soluble rocks like limestone by groundwater, these subterranean environments offer stable temperatures, constant humidity, and perpetual darkness. They are home to highly specialized organisms, often blind and depigmented, that have adapted to life without sunlight, forming unique and fragile ecosystems.

The Lithosphere’s Crucial Role in Biogeochemical Cycles

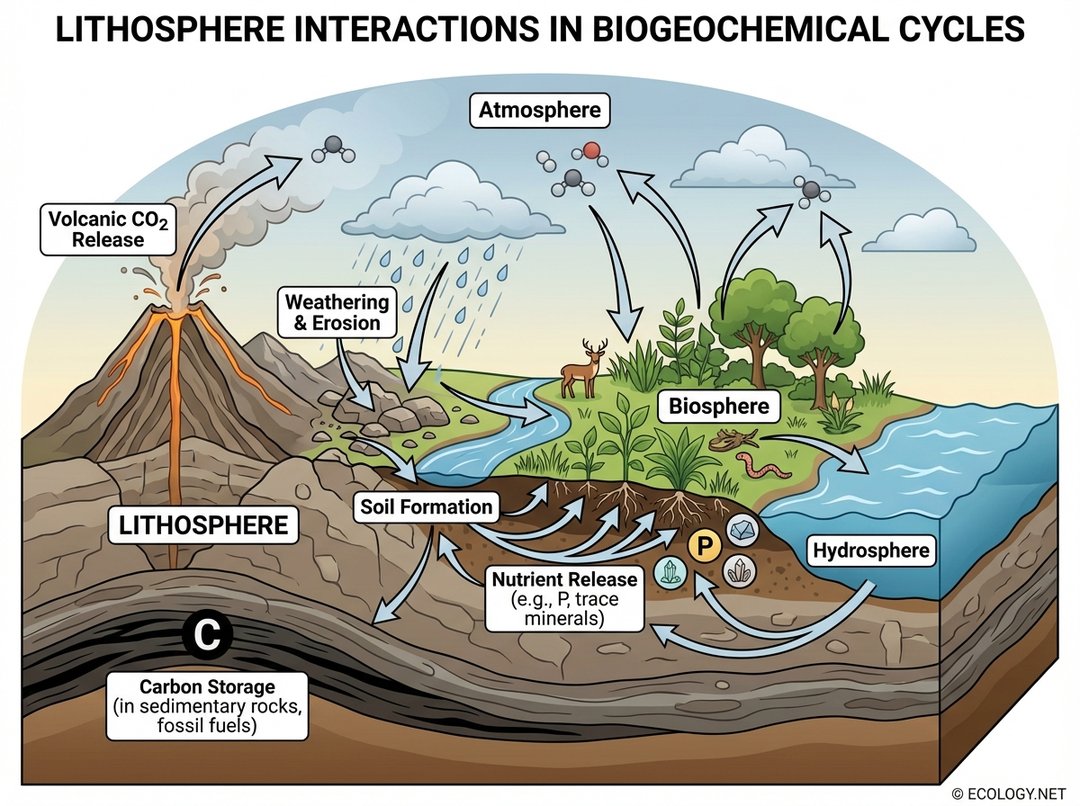

Beyond shaping landscapes, the lithosphere is an active participant in Earth’s vital biogeochemical cycles, which regulate the flow of essential elements through the planet’s living and non-living components. Its interactions with the atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere are fundamental to maintaining life on Earth.

The Rock Cycle and Soil Formation

The lithosphere is the primary reservoir for the Earth’s rocks. Through processes like weathering and erosion, rocks are broken down into smaller particles. These particles, mixed with organic matter, form soil. Soil is the foundation of terrestrial ecosystems, providing physical support, water, and nutrients for plants, which in turn support all other terrestrial life. The continuous cycling of rocks ensures a constant supply of fresh minerals for soil replenishment.

Nutrient Release: Feeding the Biosphere

As rocks weather, they release vital nutrients into the environment. Elements like phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and various trace minerals, which are essential for plant growth and overall ecosystem health, are derived from the lithosphere. These nutrients are then absorbed by plants, entering the food web and cycling through ecosystems. Without this lithospheric contribution, the productivity of many ecosystems would be severely limited.

Carbon Storage and Regulation

The lithosphere plays a critical role in the global carbon cycle. It acts as a massive long-term carbon sink, storing vast quantities of carbon in sedimentary rocks like limestone and in fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas. This geological storage helps regulate the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over geological timescales. Conversely, volcanic activity, a direct manifestation of lithospheric processes, releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, contributing to the natural greenhouse effect.

Humanity’s Intertwined Fate with the Lithosphere

Human civilization has always been intimately linked with the lithosphere. We build our homes and cities upon it, extract its resources, and cultivate its soils. However, this close relationship also brings significant responsibilities and challenges.

Resource Extraction and Its Consequences

The lithosphere provides us with essential resources: metals for industry, minerals for construction, and fossil fuels for energy. While these resources are vital for modern society, their extraction can have profound environmental impacts, including habitat destruction, soil degradation, water pollution, and landscape alteration. Sustainable mining practices and the transition to renewable energy sources are crucial for mitigating these impacts.

Land Use and Environmental Change

Our use of land, from agriculture to urbanization, directly modifies the lithosphere’s surface. Deforestation, intensive farming, and construction can lead to increased soil erosion, loss of fertility, and altered hydrological cycles. Understanding the geological context of land use decisions is paramount for preventing environmental degradation and ensuring long-term ecological stability.

Geological Hazards and Resilience

The dynamic nature of the lithosphere also presents hazards. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and landslides are natural processes that can pose significant risks to human populations. By studying the lithosphere, scientists can better predict these events, develop early warning systems, and design infrastructure that is more resilient to geological forces, thereby protecting lives and livelihoods.

Conclusion: Appreciating Our Dynamic Foundation

The lithosphere is far more than just solid ground. It is a vibrant, active component of the Earth system, constantly shaping our world, creating diverse habitats, and regulating the flow of life-sustaining elements. From the grand scale of plate tectonics to the microscopic processes of soil formation, its influence is pervasive and profound.

By deepening our understanding of this magnificent geological foundation, we can better appreciate the intricate web of life it supports and develop more sustainable practices for interacting with our planet. The lithosphere reminds us that even the most seemingly stable parts of Earth are alive with change, a constant reminder of the dynamic forces that make our world unique and habitable.