Understanding Food Systems: From Farm to Fork and Beyond

Every bite of food we take connects us to an intricate, global web of activities known as the food system. Far more than just what appears on our plate, a food system encompasses everything involved in getting food from its origin to our mouths, and even what happens to it afterward. It is a complex interplay of environmental, social, economic, and political factors that shape what we eat, how it is produced, and its impact on the planet and its people.

For too long, many of us have viewed food as a simple commodity, readily available without much thought to its journey. However, understanding the full scope of food systems is crucial for addressing some of the most pressing challenges of our time, from climate change and biodiversity loss to public health and social equity. Let us embark on a journey to unravel the fascinating and vital world of food systems.

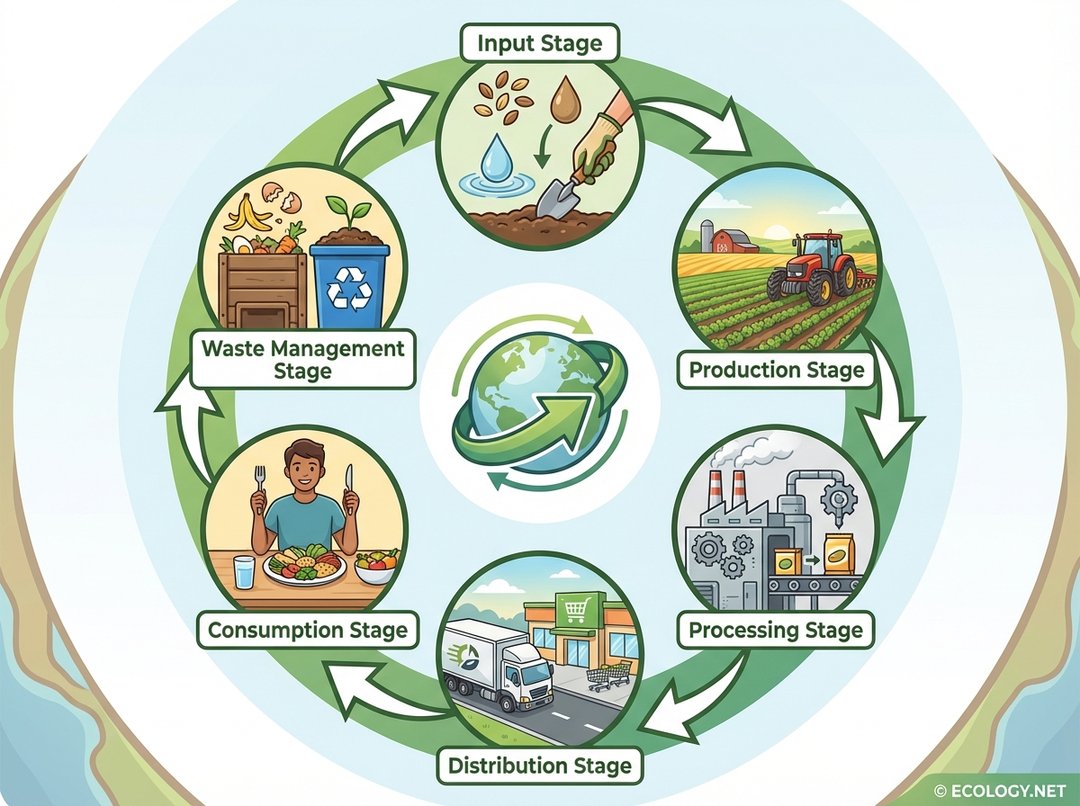

What Exactly is a Food System? A Six-Stage Journey

At its core, a food system is a pathway, a series of interconnected stages that food travels through. While the specifics can vary greatly depending on the type of food and where it is produced and consumed, most food systems can be broken down into six fundamental stages, forming a continuous, often circular, process.

The Six Stages of a Food System:

- Input Stage: The Foundation

- This initial stage involves all the resources required to produce food. Think of seeds, water, nutrients (from soil or fertilizers), energy (for machinery), labor, and land. Without these fundamental inputs, no food can be grown or raised. For example, a farmer needs quality seeds, sufficient water, and healthy soil to begin cultivating a crop of wheat.

- Production Stage: Growing and Harvesting

- This is where food is actually created. It includes farming (cultivating crops, raising livestock), fishing, aquaculture, and even hunting and gathering. This stage is heavily influenced by climate, geography, and agricultural practices. A large-scale corn farm, a small organic vegetable garden, or a fishing trawler all represent different facets of the production stage.

- Processing Stage: From Raw to Ready

- Once produced, many foods undergo some form of processing before they are ready for consumption. This can range from simple cleaning and packaging of fresh produce to complex manufacturing processes like milling grain into flour, baking bread, pasteurizing milk, or creating frozen meals. This stage often adds value and extends shelf life.

- Distribution Stage: Getting Food to People

- This stage involves the transportation, storage, and marketing of food products from processors to consumers. It includes vast global supply chains, local farmers’ markets, warehouses, supermarkets, and restaurants. The efficiency and reach of distribution networks determine how accessible food is to different populations. Think of the journey of coffee beans from a farm in Colombia to a cafe in New York City.

- Consumption Stage: Eating and Nourishment

- This is the point where food is purchased, prepared, and eaten. It encompasses everything from home cooking and family meals to dining out in restaurants, school cafeterias, and street food vendors. Consumption patterns are influenced by culture, income, personal preferences, and health considerations.

- Waste Management Stage: The End of the Cycle, or a New Beginning?

- No food system is perfectly efficient, and waste is an inevitable part of the process. This stage deals with the disposal or repurposing of food scraps, spoiled food, and packaging materials. Effective waste management, such as composting or recycling, can help close the loop and return valuable nutrients to the system, minimizing environmental impact.

The Ecology of Food Systems: Interacting with Nature

As ecologists, we recognize that food systems are not isolated human constructs; they are deeply embedded within natural ecosystems. Every stage of the food system interacts with the environment, drawing resources from it and returning various outputs, some beneficial, others detrimental. Understanding these ecological connections is paramount to building resilient and sustainable food futures.

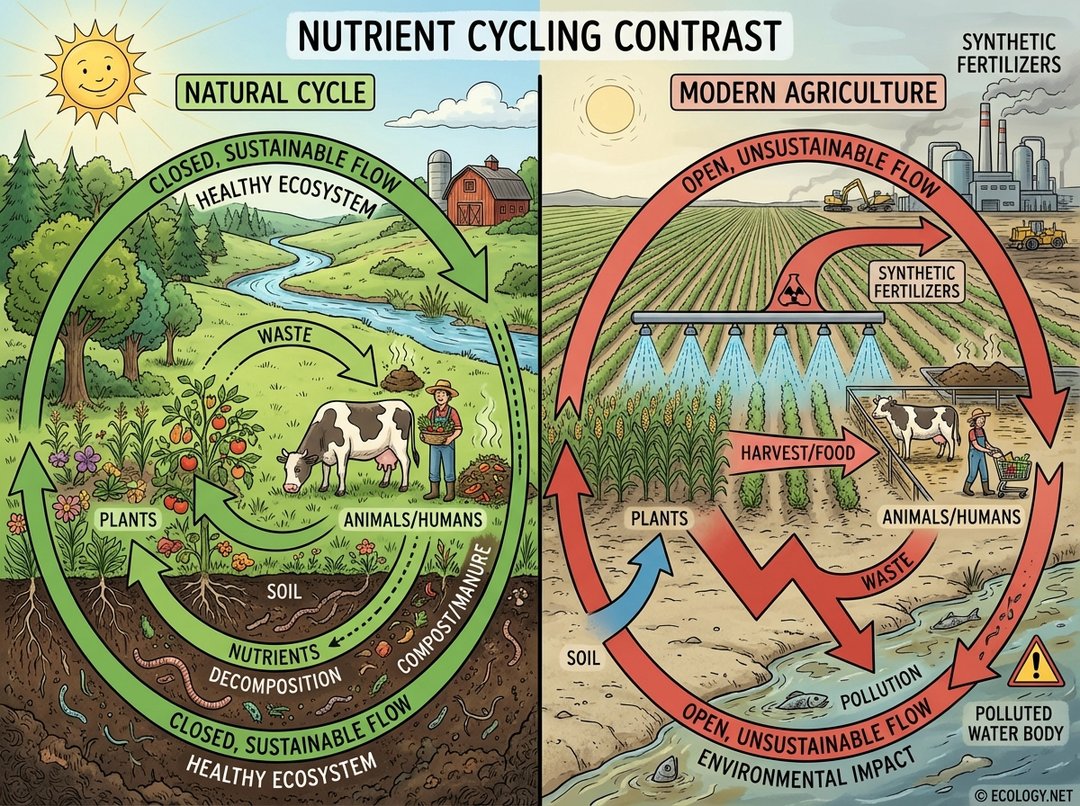

Nutrient Cycling: The Lifeblood of Soil

One of the most fundamental ecological principles at play in food systems is nutrient cycling. Plants draw essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium from the soil. These nutrients then move up the food chain as animals consume plants, and humans consume both plants and animals. In a natural, healthy ecosystem, these nutrients are returned to the soil through decomposition of organic matter, animal waste, and dead organisms, completing a closed loop.

However, modern industrial agriculture often disrupts this natural cycle. Large quantities of synthetic fertilizers are applied to boost yields, and much of the nutrient-rich waste from farms and urban centers is not returned to agricultural land. Instead, it often ends up in landfills or pollutes waterways, leading to nutrient imbalances in the soil and harmful algal blooms in rivers and oceans. This creates an “open loop” system, where nutrients are extracted but not fully replenished naturally, requiring continuous external inputs.

Water, Land, and Biodiversity: Precious Resources

- Water Use: Food production is incredibly water-intensive. Irrigation for crops, water for livestock, and water used in processing facilities place immense demands on freshwater resources. Growing a single almond, for example, can require several liters of water, and rice paddies are notorious for their high water consumption. Over-extraction of water for agriculture can deplete aquifers and dry up rivers, impacting ecosystems and human communities.

- Land Use: Agriculture is the largest user of land globally. Forests are cleared for farmland, grasslands are converted for grazing, and wetlands are drained for cultivation. This habitat destruction is a primary driver of biodiversity loss. Monoculture farming, where vast fields are dedicated to a single crop, further reduces biodiversity both above and below ground, making ecosystems more vulnerable to pests and diseases.

- Biodiversity: A healthy food system relies on a rich tapestry of biodiversity. Pollinators like bees and butterflies are essential for many crops. Soil microorganisms break down organic matter and make nutrients available to plants. Genetic diversity within crops and livestock provides resilience against diseases and changing climates. Industrial farming practices, including widespread pesticide use and monocultures, can severely diminish this vital biodiversity.

Energy Footprint and Climate Impact

The entire food system is a significant consumer of energy, primarily from fossil fuels. This energy is used for:

- Farm machinery: Tractors, harvesters, irrigation pumps.

- Fertilizer production: Manufacturing synthetic nitrogen fertilizers is an energy-intensive process.

- Processing: Running factories, refrigeration, cooking.

- Transportation: Moving food across continents and within local areas.

- Storage: Refrigeration in warehouses and grocery stores.

The burning of fossil fuels at each of these stages releases greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change. Furthermore, certain agricultural practices, such as methane emissions from livestock and nitrous oxide from fertilized soils, are potent greenhouse gas sources themselves.

Challenges in Modern Food Systems: A Global Perspective

While modern food systems have achieved remarkable feats in increasing food production, they also face profound challenges that threaten both environmental sustainability and human well-being.

Environmental Degradation

- Soil Erosion and Degradation: Intensive farming practices, lack of crop rotation, and excessive tilling can strip the soil of its organic matter and lead to severe erosion, reducing fertility and increasing desertification.

- Water Pollution: Runoff from farms containing pesticides, herbicides, and excess fertilizers contaminates rivers, lakes, and oceans, harming aquatic life and human health.

- Deforestation and Habitat Loss: The expansion of agricultural land, particularly for commodity crops like soy and palm oil, is a major driver of deforestation in critical ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: As discussed, the food system is a significant contributor to climate change, from farm to landfill.

Social and Economic Inequities

- Food Waste: Globally, an estimated one-third of all food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted. This represents a colossal waste of resources, including land, water, and energy, and contributes to landfill emissions.

- Food Insecurity and Malnutrition: Despite abundant food production, millions still suffer from hunger and malnutrition, often due to issues of access, affordability, and distribution rather than a lack of food itself.

- Labor Exploitation: Workers in various stages of the food system, from farm laborers to processing plant employees, often face poor working conditions, low wages, and limited rights.

- Health Impacts: The prevalence of highly processed, calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods in many modern diets contributes to rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related diseases.

Towards More Sustainable Food Systems: A Path Forward

Recognizing these challenges, there is a growing global movement towards transforming our food systems to be more sustainable, equitable, and resilient. This involves a holistic approach that considers ecological principles, social justice, and economic viability.

Key Pillars of Sustainable Food Systems:

- Agroecology and Regenerative Agriculture:

- These approaches focus on working with nature rather than against it. They emphasize practices that build soil health, enhance biodiversity, conserve water, and minimize synthetic inputs. Examples include:

- Cover Cropping: Planting non-cash crops between growing seasons to protect soil, add organic matter, and suppress weeds.

- No-Till Farming: Minimizing soil disturbance to prevent erosion and maintain soil structure.

- Crop Rotation: Varying crops grown in a field over time to improve soil fertility and break pest cycles.

- Integrated Pest Management: Using natural predators and biological controls instead of relying solely on chemical pesticides.

- These approaches focus on working with nature rather than against it. They emphasize practices that build soil health, enhance biodiversity, conserve water, and minimize synthetic inputs. Examples include:

- Local and Seasonal Food:

- Supporting local farmers and consuming foods that are in season reduces the energy required for transportation and storage. It also strengthens local economies and fosters a connection between consumers and their food sources. Farmers’ markets, community supported agriculture (CSAs), and farm-to-table initiatives are excellent examples.

- Reduced Food Waste:

- Addressing food waste at every stage is critical. This includes improving storage and infrastructure, educating consumers on meal planning and proper food handling, and diverting unavoidable food waste to composting or animal feed.

- Dietary Shifts:

- Promoting more plant-rich diets, reducing excessive meat consumption, and choosing sustainably sourced animal products can significantly lower the environmental footprint of our food choices. Plant-based proteins often require less land and water and generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions than animal proteins.

- Policy and Consumer Choices:

- Government policies can incentivize sustainable farming practices, regulate food waste, and ensure fair labor conditions. Consumers, through their purchasing decisions, have immense power to drive demand for more sustainable and ethically produced food. Choosing certified organic, fair trade, or locally grown products are examples of impactful consumer actions.

The Future of Food Systems: A Collective Responsibility

The journey of food from its origins to our plates is a testament to human ingenuity and our deep connection to the natural world. However, the current trajectory of many food systems is unsustainable. By understanding the intricate stages and ecological impacts of how we produce, process, distribute, consume, and manage our food, we can begin to envision and build a better future.

Transforming food systems is not a task for a single individual or sector; it requires collective action from farmers, policymakers, businesses, scientists, and consumers. Every choice we make about food has ripple effects throughout the system. By embracing sustainable practices, supporting local initiatives, reducing waste, and advocating for change, we can cultivate food systems that nourish both people and the planet for generations to come.