Unveiling Endemism: Earth’s Unique Biological Treasures

Imagine a creature so rare, so utterly unique, that it exists nowhere else on Earth but in one specific corner of our planet. This isn’t a fantasy; it’s a fundamental concept in ecology known as endemism. Endemic species are nature’s masterpieces, living proof of evolution’s incredible power to adapt life to specific environments, creating a tapestry of biodiversity that is both fragile and awe-inspiring. Understanding endemism is crucial for appreciating the intricate web of life and for guiding our efforts to protect it.

What Exactly is Endemism?

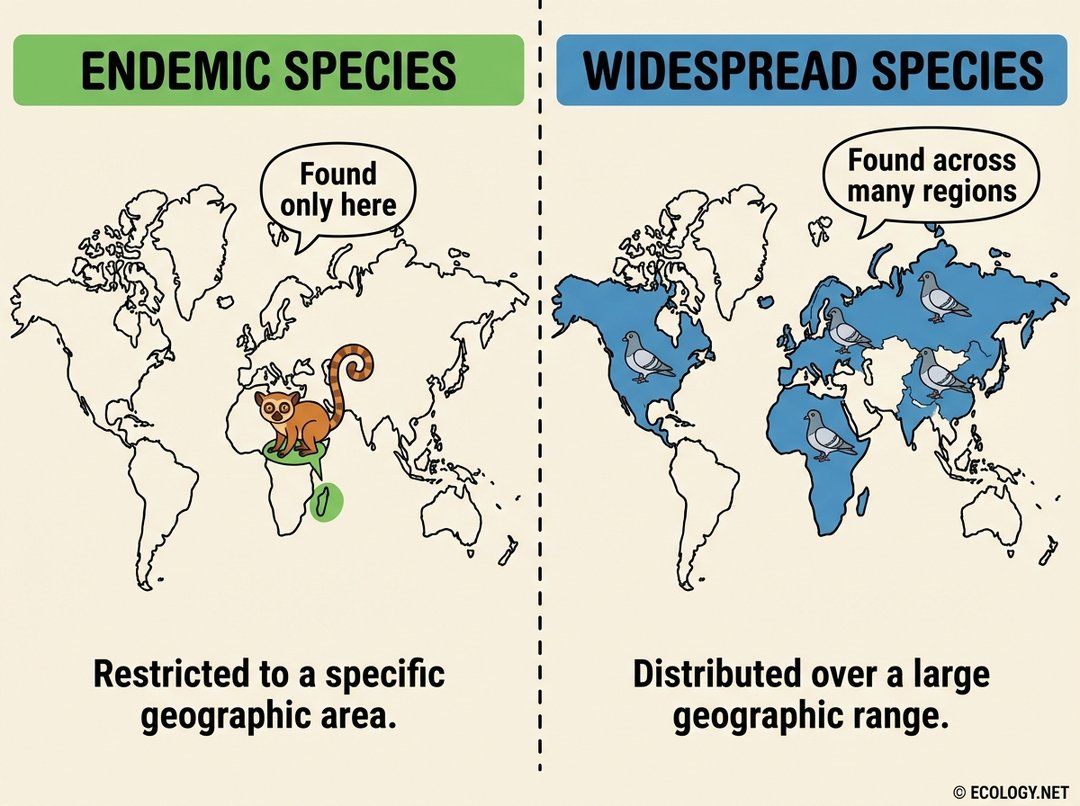

At its core, endemism describes the ecological state of a species being unique to a defined geographic location, such as an island, a mountain range, a lake, or even a single cave system. These species are found exclusively in that particular area and nowhere else in the world. They are the biological signatures of their native habitats.

To grasp this concept fully, it is helpful to contrast it with widespread species. A widespread species, like the common pigeon or a dandelion, can be found across vast continents and diverse climates. An endemic species, however, has a much more restricted address.

This distinction highlights the special vulnerability and ecological significance of endemic life forms. Their limited distribution means they are often more susceptible to environmental changes, habitat destruction, and other threats, making their conservation a high priority.

The Genesis of Uniqueness: How Endemism Arises

The existence of an endemic species is not a random occurrence but rather the result of powerful evolutionary and geological processes working over vast stretches of time. Several key factors contribute to the development of endemism.

Geographic Isolation: Islands of Life

One of the most significant drivers of endemism is geographic isolation. When a population of organisms becomes physically separated from its main group by a barrier it cannot cross, such as an ocean, a mountain range, or a desert, it begins to evolve independently. Over generations, these isolated populations adapt to their unique local conditions, leading to genetic divergence and, eventually, the formation of new species. Islands are classic examples of this phenomenon, often hosting an extraordinary number of endemic species.

Consider the Galapagos finches, famously studied by Charles Darwin. A small group of ancestral finches arrived on the isolated Galapagos Islands and, over millions of years, diversified into numerous distinct species, each adapted to a specific food source or niche on different islands. Each of these finch species is endemic to the Galapagos. Similarly, the lemurs of Madagascar are a prime example of a group of mammals that evolved in isolation on a large island, resulting in hundreds of endemic species found nowhere else.

Ecological Specialization: Niche Dwellers

Even without complete geographic isolation, species can become endemic through extreme ecological specialization. This occurs when a species adapts so precisely to a very specific set of environmental conditions or a particular resource that it cannot thrive elsewhere. For instance, a plant species might evolve to grow only on a particular type of soil with a unique mineral composition, or an insect might feed exclusively on a single, rare plant species. Such tight ecological bonds restrict their range, making them endemic to the areas where their specific requirements are met.

Evolutionary History: Ancient Lineages and Relicts

Sometimes, endemism is a relic of a species’ long evolutionary history. A species might have once had a much wider distribution but, due to climate change, geological shifts, or competition, its range has gradually shrunk to a small, isolated pocket. These are often referred to as relict species. The Wollemi Pine in Australia, once thought to be extinct and only known from fossils, was discovered alive in a remote gorge in 1994, existing as a critically endangered endemic species in that tiny, protected area. It is a living fossil, a testament to ancient lineages surviving in a modern world.

The Spectrum of Endemism: Narrow vs. Wide

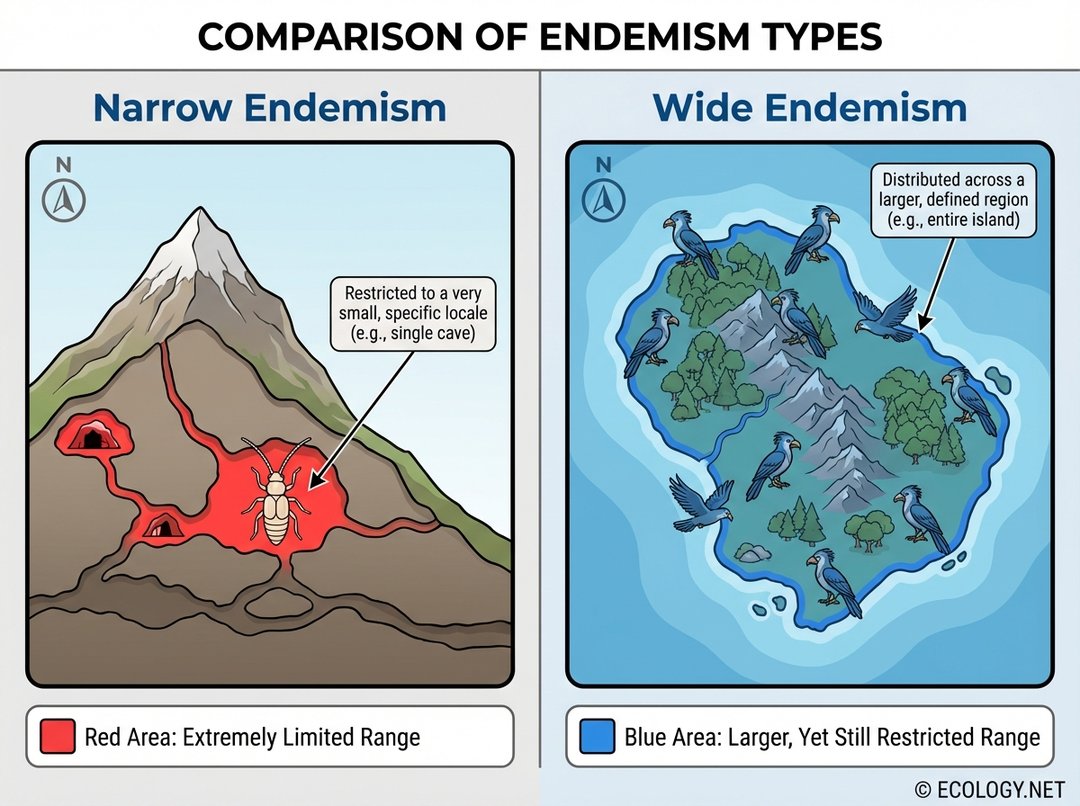

Endemism is not a single, uniform state; it exists along a spectrum. Ecologists often distinguish between different degrees of endemism, primarily based on the size of the geographic area a species occupies.

Narrow Endemism: The Ultra-Specialists

Narrow endemism refers to species found in extremely restricted geographic areas. These could be a single mountain peak, a specific cave system, a unique hot spring, or a small patch of forest. Species exhibiting narrow endemism are often highly specialized and particularly vulnerable to any disturbance within their tiny habitat.

- Examples:

- Many cave-dwelling fish or insects, adapted to specific subterranean conditions.

- Certain plant species found only on a single volcanic crater or a unique rock outcrop.

- The Devil’s Hole Pupfish, which lives in a single, isolated pool in Nevada.

Their extreme localization makes them ecological gems but also places them at the highest risk of extinction if their habitat is altered or destroyed.

Wide Endemism: Regional Uniqueness

In contrast, wide endemism describes species whose distribution is restricted to a larger, but still defined, geographic region. This could be an entire island, a large mountain range, a significant river basin, or a distinct biogeographic province. While their range is broader than narrow endemics, they are still unique to that region and found nowhere else globally.

- Examples:

- All species of lemurs are endemic to Madagascar.

- The vast majority of marsupials are endemic to Australia and New Guinea.

- The unique flora and fauna of the Hawaiian Islands, such as the Nene goose or the Silversword plant, are endemic to the archipelago.

These species are still critically important for the biodiversity of their respective regions, and their loss would represent an irreplaceable global loss.

Why Endemism Matters: A Cornerstone of Biodiversity and Conservation

The study and protection of endemic species are paramount for several reasons, touching upon biodiversity, ecosystem health, and the very fabric of life on Earth.

Indicators of Biodiversity Hotspots

Regions with a high concentration of endemic species are often designated as biodiversity hotspots. These areas are not only rich in unique life but are also typically under significant threat from human activities. Identifying and protecting these hotspots is a strategic approach to conserving a large portion of the world’s biodiversity. The presence of many endemic species signals a unique evolutionary history and a complex, thriving ecosystem.

Vulnerability and Extinction Risk

The most pressing concern regarding endemic species is their heightened vulnerability to extinction. Their restricted ranges mean that any localized threat can have catastrophic consequences.

- Habitat Loss: The primary threat. If the only forest an endemic bird lives in is cleared, the species is gone forever.

- Climate Change: Even slight shifts in temperature or rainfall can push specialized endemic species beyond their tolerance limits, especially those in small, isolated habitats.

- Invasive Species: Non-native species introduced to an endemic area can outcompete, prey upon, or introduce diseases to native endemics, which often lack defenses against these new threats.

- Pollution: Contamination of their limited habitat can quickly decimate populations.

The extinction of an endemic species represents an irreversible loss, a unique branch of the tree of life forever severed.

Ecosystem Services and Unique Roles

Endemic species often play unique and irreplaceable roles within their ecosystems. They may be the sole pollinators for certain plants, critical components of local food webs, or key players in nutrient cycling. Their loss can trigger a cascade of negative effects, destabilizing the entire ecosystem. For example, if an endemic insect is the only pollinator for an endemic plant, the loss of one could lead to the extinction of both.

Global Hotspots of Endemism

Certain regions around the world are renowned for their extraordinary levels of endemism, making them critical areas for conservation efforts.

- Madagascar: An island nation off the coast of Africa, home to an incredible array of endemic species, including all lemurs, two-thirds of the world’s chameleon species, and thousands of unique plants.

- Galapagos Islands: Famous for its unique reptiles, birds, and plants, many of which are found nowhere else, such as the Galapagos giant tortoise and marine iguana.

- Hawaiian Islands: Despite their small land area, these remote Pacific islands boast an astonishing number of endemic birds, insects, and plants, a result of millions of years of isolation.

- Cape Floristic Region, South Africa: A relatively small area with an unparalleled diversity of plant life, with an extremely high percentage of endemic plant species.

- Mediterranean Basin: While not an island, its unique climate and geological history have fostered a high degree of plant endemism.

These regions serve as living laboratories of evolution and stark reminders of the preciousness of unique life.

Protecting the Unique: Conservation Strategies

Given their vulnerability, the conservation of endemic species requires targeted and often intensive efforts.

Habitat Preservation and Restoration

The most direct way to protect endemic species is to safeguard their habitats. This involves establishing protected areas, national parks, and reserves, as well as restoring degraded ecosystems to ensure that endemic species have the space and resources they need to survive.

Invasive Species Management

Controlling and eradicating invasive species is critical, especially on islands and in other isolated ecosystems where native endemics are particularly susceptible. This can involve physical removal, biological controls, or public education campaigns to prevent new introductions.

Climate Change Mitigation

Addressing global climate change is essential for the long-term survival of many endemic species, particularly those with narrow ranges that cannot easily shift to more favorable climates. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions and developing climate adaptation strategies are vital.

Research and Monitoring

Understanding the biology, ecology, and population dynamics of endemic species is crucial for effective conservation. Ongoing research and monitoring help scientists track populations, identify threats, and develop informed conservation plans.

Conclusion: Celebrating Earth’s Unique Treasures

Endemism is a powerful concept that underscores the incredible diversity and specificity of life on Earth. It reminds us that every corner of our planet, no matter how small, can harbor unique evolutionary stories and irreplaceable biological treasures. These endemic species are not just biological curiosities; they are vital components of global biodiversity, indicators of ecosystem health, and a testament to the enduring power of evolution. By understanding, appreciating, and actively protecting these unique forms of life, we safeguard not only individual species but also the intricate, beautiful, and irreplaceable web of life that sustains us all.