Imagine Earth as a giant, breathing organism. Just as our lungs take in oxygen and release carbon dioxide, our planet has natural systems that absorb and store carbon, playing a vital role in maintaining a stable climate. These incredible natural systems are what scientists call carbon sinks.

In an era where atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are a major concern, understanding these carbon sinks is not just for scientists; it is crucial for everyone. They are our planet’s primary defense mechanism against runaway climate change, working tirelessly to remove excess carbon from the atmosphere and lock it away.

What Exactly is a Carbon Sink?

A carbon sink is essentially any natural or artificial reservoir that absorbs and stores more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases. Think of it as a natural sponge for carbon dioxide. This process is a fundamental part of Earth’s carbon cycle, a complex system that moves carbon between the atmosphere, oceans, land, and living organisms.

Without these sinks, the carbon dioxide released from natural processes and human activities would accumulate much faster in the atmosphere, leading to more rapid global warming. Carbon sinks help to regulate Earth’s temperature, making our planet habitable.

Earth’s Major Carbon Sinks: Our Planetary Reservoirs

Our planet boasts several powerful carbon sinks, each with unique characteristics and capacities. These natural reservoirs are critical for maintaining the delicate balance of carbon in our environment.

Forests and Terrestrial Vegetation

Perhaps the most visible and widely recognized carbon sinks are our planet’s forests. Through the process of photosynthesis, trees and other plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, converting it into organic matter like wood, leaves, and roots. This carbon remains stored in the plant biomass for the duration of its life. Old-growth forests, with their massive trees and dense undergrowth, can store enormous amounts of carbon for centuries.

- Example: The Amazon Rainforest, often called the “lungs of the Earth,” stores billions of tons of carbon in its trees and vegetation. Similarly, boreal forests across Canada, Russia, and Scandinavia hold vast carbon reserves.

Oceans

The world’s oceans are by far the largest active carbon sink on Earth, holding approximately 50 times more carbon than the atmosphere. They absorb carbon dioxide in several ways, acting as a massive buffer against atmospheric changes.

- Physical Pump: CO2 dissolves directly into the surface waters of the ocean, much like how a carbonated drink absorbs CO2. Colder waters absorb more CO2 than warmer waters.

- Biological Pump: Marine organisms, particularly microscopic plants called phytoplankton, absorb CO2 for photosynthesis. When these organisms die, their carbon-rich remains sink to the deep ocean, locking carbon away for long periods.

- Chemical Pump: CO2 reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid, which then participates in a series of chemical reactions involving carbonates and bicarbonates, further storing carbon.

Soils

Beneath our feet, soils represent another significant carbon sink. Organic matter, derived from decaying plants and animals, is rich in carbon. Microbes in the soil break down this matter, but a substantial portion of the carbon can remain stored in the soil for decades to centuries, especially in peatlands and permafrost regions.

- Example: Peatlands, found in wetlands across the globe, are incredibly efficient carbon sinks, storing more carbon per acre than forests. Agricultural soils, when managed sustainably, can also be enhanced to store more carbon.

Geological Formations

Over geological timescales, carbon can be locked away in rocks and fossil fuels deep within the Earth’s crust. This is a very slow process, but it represents the ultimate long-term storage of carbon. Fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas are essentially ancient carbon sinks, formed from organic matter buried and transformed over millions of years.

How Carbon Sinks Work: The Intricate Mechanisms

Delving deeper, the processes by which carbon sinks operate are fascinating and complex, involving a delicate interplay of physical, chemical, and biological forces.

Terrestrial Carbon Sequestration

On land, the primary mechanism is photosynthesis. Plants use sunlight to convert atmospheric CO2 and water into glucose (energy) and oxygen. The carbon becomes part of the plant’s structure. When plants die, this carbon can be transferred to the soil as organic matter. Soil microbes then decompose this matter, releasing some CO2 back, but a significant portion can be stabilized and stored in the soil for extended periods, especially in healthy, undisturbed ecosystems.

- Example: A growing tree sequesters carbon in its trunk, branches, and roots. When leaves fall and decompose, their carbon contributes to the soil’s organic content.

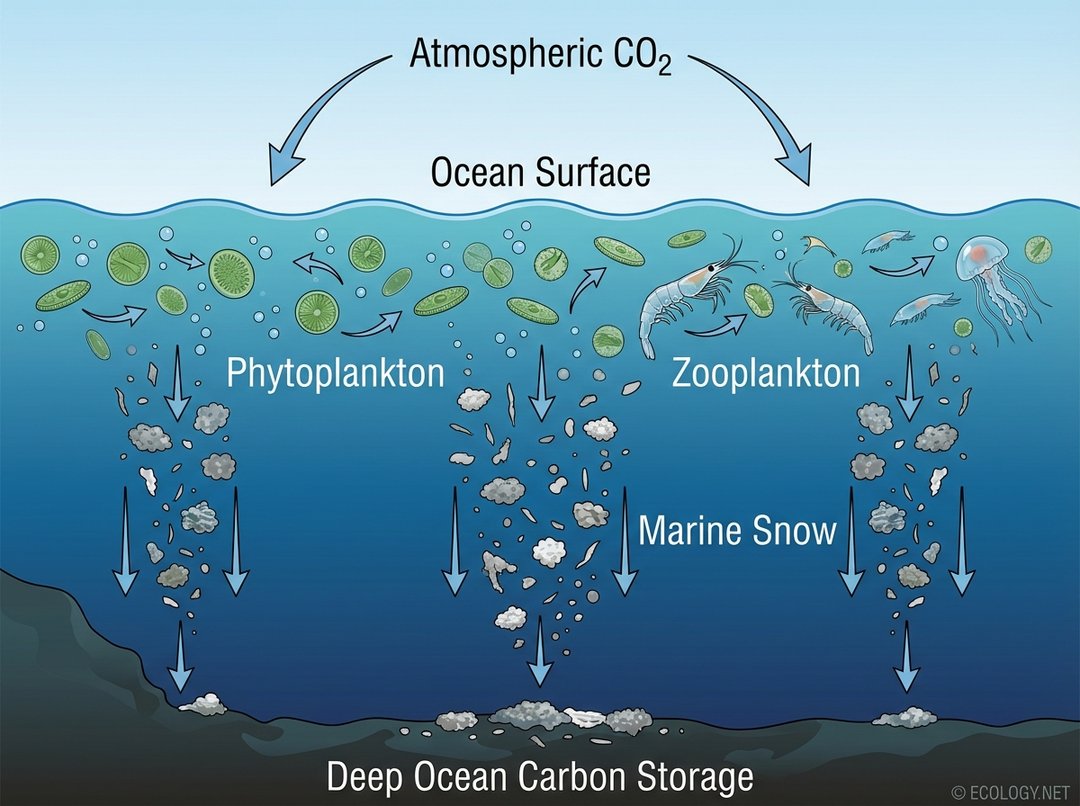

Oceanic Carbon Sequestration: The Biological Pump in Action

The ocean’s ability to absorb carbon is particularly intricate. While direct dissolution of CO2 is important, the biological pump is a powerful engine for moving carbon from the surface to the deep ocean.

- Atmospheric CO2 Dissolves: Carbon dioxide from the atmosphere dissolves into the ocean surface waters.

- Phytoplankton Absorption: Microscopic marine plants, called phytoplankton, absorb this dissolved CO2 during photosynthesis, forming the base of the marine food web.

- Zooplankton Consumption: Tiny marine animals, zooplankton, graze on the phytoplankton, incorporating carbon into their bodies.

- Sinking Marine Snow: When phytoplankton, zooplankton, and other marine organisms die, or when zooplankton produce fecal pellets, their carbon-rich remains clump together to form “marine snow.” This organic debris slowly sinks through the water column.

- Deep Ocean Carbon Storage: A significant portion of this marine snow reaches the deep ocean, where the carbon can be stored for hundreds to thousands of years, effectively removing it from active circulation with the atmosphere.

The biological pump is a testament to the power of microscopic life in regulating global climate. Without these tiny organisms, the ocean’s capacity to store carbon would be dramatically reduced.

The Indispensable Importance of Carbon Sinks

The health and functionality of carbon sinks are paramount for the well-being of our planet and all its inhabitants. Their importance extends far beyond just climate regulation.

- Climate Change Mitigation: They are our primary natural allies in the fight against climate change, removing billions of tons of CO2 from the atmosphere annually, thereby slowing global warming.

- Atmospheric Regulation: Carbon sinks help maintain the delicate balance of atmospheric gases, preventing excessive CO2 buildup that could lead to extreme weather events and ecosystem disruption.

- Biodiversity Support: Healthy forests, oceans, and soils are not just carbon sinks; they are vibrant ecosystems that support an incredible diversity of life, from microscopic organisms to apex predators.

- Ecosystem Services: Beyond carbon sequestration, these natural systems provide countless other services, such as clean air and water, fertile soils for agriculture, timber, fisheries, and recreational opportunities.

Threats to Our Natural Carbon Sinks

Despite their critical role, carbon sinks are under immense pressure from human activities and the very climate change they help to mitigate.

- Deforestation and Land Degradation: The clearing of forests for agriculture, logging, and urbanization releases stored carbon back into the atmosphere and reduces the planet’s capacity to absorb more. Degradation of soils through unsustainable farming practices also diminishes their carbon storage potential.

- Ocean Acidification: As the ocean absorbs more CO2, its chemistry changes, becoming more acidic. This ocean acidification threatens marine life, particularly organisms that build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate, such as corals and shellfish, which are vital components of the biological pump.

- Permafrost Thaw: Arctic permafrost contains vast amounts of ancient carbon. As global temperatures rise, permafrost thaws, releasing methane and CO2, creating a dangerous positive feedback loop that accelerates warming.

- Wildfires: Increased frequency and intensity of wildfires, often linked to climate change, release massive amounts of stored carbon from forests back into the atmosphere.

Protecting and Enhancing Carbon Sinks: A Path Forward

Given their vital role, protecting and actively enhancing our natural carbon sinks is one of the most effective strategies for combating climate change. This requires a multi-faceted approach, combining conservation with restoration and sustainable management.

Reforestation and Afforestation

Planting new trees (afforestation) and restoring degraded forests (reforestation) are powerful ways to increase terrestrial carbon sequestration. Every tree planted contributes to drawing down atmospheric CO2.

- Practical Insight: Supporting organizations involved in large-scale tree planting initiatives or participating in local community tree planting events directly contributes to enhancing this carbon sink.

Sustainable Land Management

Implementing practices that improve soil health can significantly boost carbon storage in agricultural lands and grasslands. Techniques like no-till farming, cover cropping, and agroforestry increase organic matter in the soil.

- Example: Regenerative agriculture practices not only improve soil fertility and water retention but also actively sequester carbon, turning farms into carbon sinks.

Protecting Blue Carbon Ecosystems

Coastal and marine ecosystems like mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass beds are incredibly efficient at storing carbon, often referred to as “blue carbon.” They sequester carbon at rates many times higher than terrestrial forests and store it for millennia in their sediments.

- Practical Insight: Supporting marine protected areas and initiatives that restore coastal habitats helps safeguard these invaluable blue carbon sinks.

Ocean Conservation

Reducing pollution, preventing overfishing, and mitigating ocean acidification are crucial for maintaining the health of marine ecosystems and their capacity to absorb carbon. Protecting marine biodiversity ensures the biological pump continues to function effectively.

Policy and Innovation

Government policies that incentivize carbon sequestration, such as carbon credits for sustainable forestry, and investments in research for innovative carbon capture technologies, also play a role in supporting and expanding carbon sink capabilities.

Conclusion: Our Shared Responsibility

Carbon sinks are not just abstract scientific concepts; they are living, breathing components of our planet’s life support system. From the towering trees of ancient forests to the microscopic phytoplankton in the vast oceans, these natural wonders work tirelessly to keep our climate stable.

Understanding carbon sinks empowers us to appreciate their immense value and recognize our shared responsibility in their protection. By supporting conservation efforts, adopting sustainable practices, and advocating for policies that prioritize environmental health, we can help ensure these vital planetary reservoirs continue to thrive, safeguarding a stable climate for generations to come.