Understanding Desertification: A Global Challenge for Our Lands

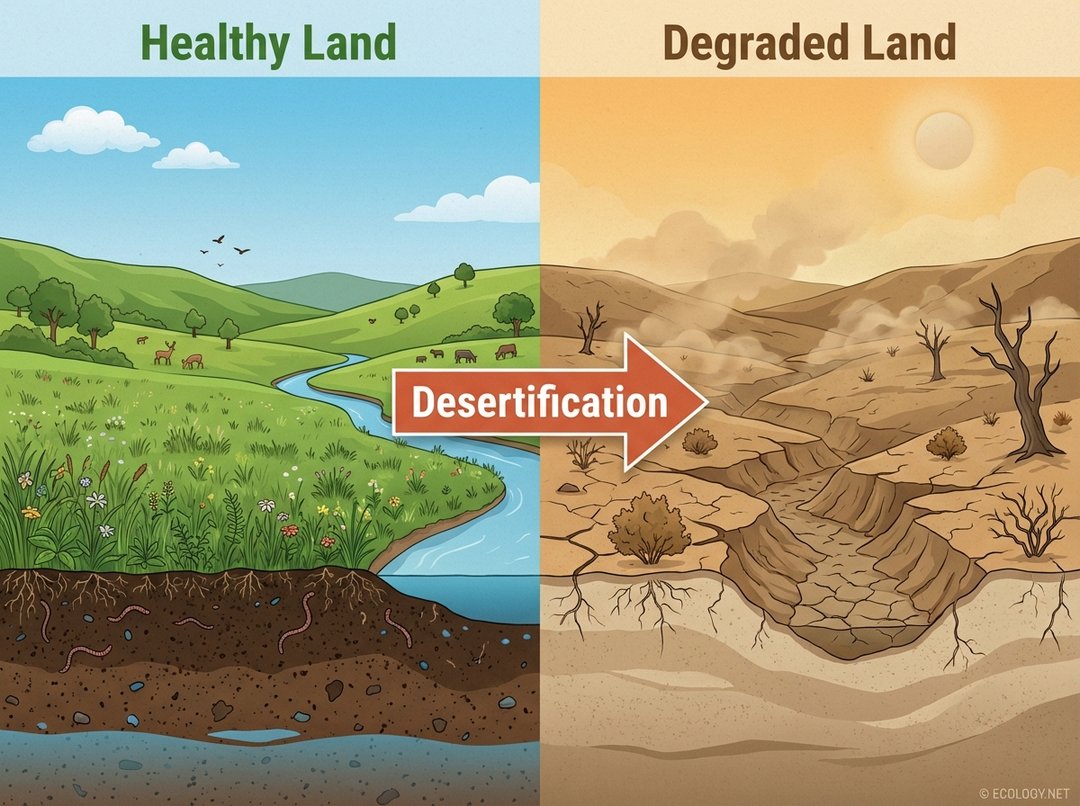

Imagine a vibrant, fertile landscape, teeming with life and productivity. Now, picture that same land slowly transforming, losing its greenery, its soil becoming barren and cracked, unable to sustain life as it once did. This isn’t just the natural expansion of deserts; it is a profound environmental process known as desertification. Far from being a distant problem, desertification affects vast swathes of our planet, impacting ecosystems, economies, and the lives of billions. It is a silent crisis, often misunderstood, yet its consequences resonate globally.

What Exactly is Desertification? Beyond Just Deserts

Desertification is not the literal spread of existing deserts. Instead, it is a form of land degradation occurring in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid areas, collectively known as drylands. These drylands, covering over 40% of the Earth’s land surface, are home to more than two billion people. The process involves the persistent degradation of dryland ecosystems by human activities and climatic variations. It means productive land loses its biological potential, becoming less fertile and less capable of supporting vegetation, wildlife, and human populations.

Consider a lush pasture in a semi-arid region. If it is overgrazed by livestock, the protective grass cover diminishes. The exposed soil then becomes vulnerable to wind and water erosion, losing its precious topsoil and nutrients. Over time, this once-productive pasture can resemble a desert, even though it is far from a natural desert biome. This transformation from healthy, productive land to degraded, desert-like conditions is the essence of desertification.

The Global Scope: Where is it Happening?

Desertification is a truly global phenomenon, affecting every continent except Antarctica. Regions particularly vulnerable include:

- The Sahel Region of Africa: Stretching across the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, this area is a classic example where a combination of climate variability and human pressures has led to widespread land degradation.

- The Mediterranean Basin: Countries like Spain, Italy, and Greece face significant desertification risks due to droughts, wildfires, and intensive agriculture.

- Central Asia: The Aral Sea disaster, where unsustainable irrigation practices led to the shrinking of a massive lake, is a stark reminder of desertification’s impact on water resources and surrounding lands.

- Parts of China and India: Rapid population growth and agricultural expansion in dryland regions contribute to significant land degradation.

- The American Southwest and Mexico: These regions experience increasing aridity and pressure on land resources, leading to desertification.

These areas are often characterized by fragile ecosystems, making them highly susceptible to the impacts of both natural climate fluctuations and human activities.

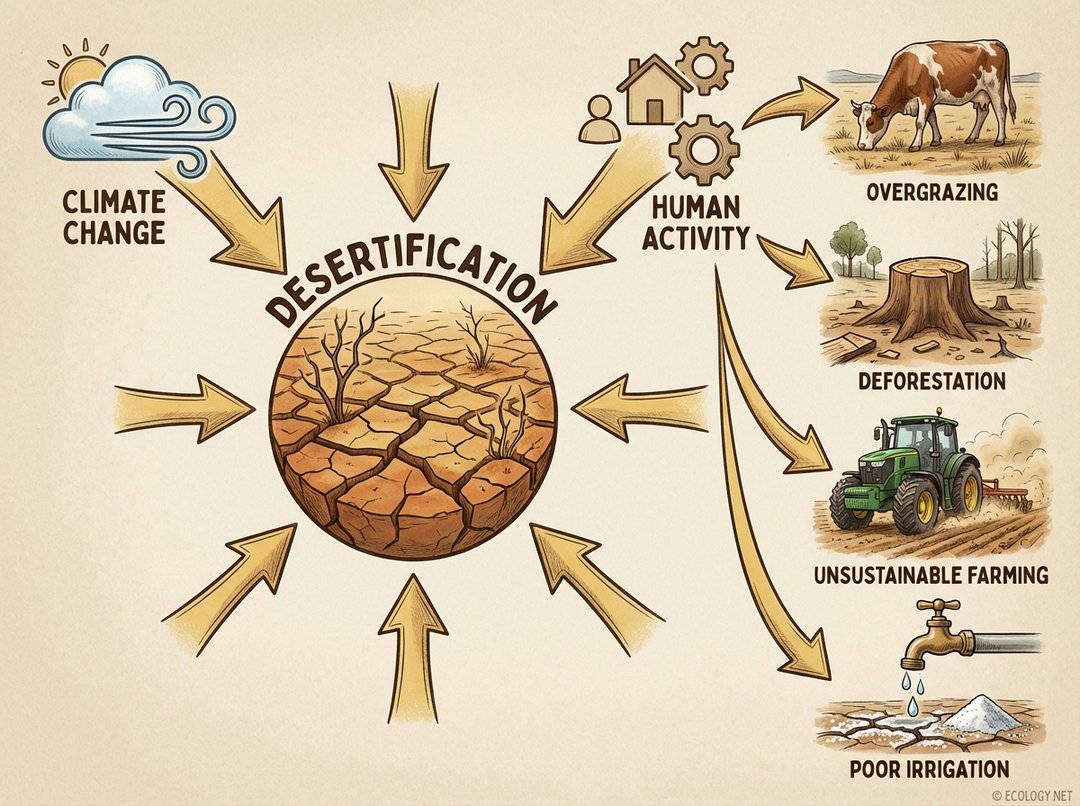

What Drives the Transformation? The Causes of Desertification

Desertification is a complex problem with multiple interacting causes, often categorized into climatic factors and human activities. It is rarely a single cause but rather a confluence of pressures that push an ecosystem past its tipping point.

Climatic Factors: The Role of Nature

- Droughts: Prolonged periods of abnormally low rainfall are a natural feature of dryland climates. While ecosystems are adapted to some level of drought, increasing frequency and intensity, often linked to climate change, can overwhelm their resilience.

- Climate Change: Beyond just droughts, global climate change can alter rainfall patterns, increase temperatures, and intensify extreme weather events, all of which exacerbate land degradation in drylands. Higher temperatures increase evaporation, drying out soils and vegetation more quickly.

Human Activities: Our Footprint on the Land

Human actions are often the primary accelerators of desertification, pushing fragile dryland ecosystems beyond their natural capacity to recover.

- Overgrazing: When too many livestock graze on a limited area, they consume vegetation faster than it can regenerate. This removes the protective plant cover, compacts the soil with their hooves, and exposes it to erosion.

- Example: In parts of the African Sahel, traditional pastoralist communities, facing shrinking grazing lands and increased herd sizes, inadvertently contribute to the degradation of their vital rangelands.

- Deforestation: The clearing of forests and woodlands for agriculture, timber, or fuel removes the tree cover that anchors soil, provides shade, and contributes to local moisture cycles. Without trees, soil is easily eroded by wind and rain.

- Example: The clearing of dryland forests in regions like Madagascar for charcoal production or slash-and-burn agriculture leaves behind barren, eroded hillsides.

- Unsustainable Farming Practices: Agricultural methods that deplete soil nutrients, compact soil, or leave it exposed are major drivers. These include:

- Monoculture: Planting the same crop repeatedly without rotation depletes specific nutrients and makes the soil less resilient.

- Intensive Tillage: Plowing deeply and frequently breaks down soil structure, making it more susceptible to erosion.

- Lack of Cover Crops: Leaving fields bare between growing seasons exposes the soil to the elements.

- Example: The “Dust Bowl” phenomenon in the American Great Plains in the 1930s was a catastrophic example of desertification driven by drought combined with unsustainable farming practices that left vast tracts of land vulnerable to wind erosion.

- Poor Irrigation Practices: While irrigation can make drylands productive, improper techniques can lead to salinization. If water is not drained properly, it evaporates, leaving behind salts that accumulate in the topsoil, making it toxic for most plants.

- Example: Many ancient civilizations collapsed partly due to salinization from irrigation, and it remains a problem in modern agricultural regions, particularly in Central Asia and parts of the Middle East.

- Urbanization and Infrastructure Development: The expansion of cities, roads, and other infrastructure can fragment natural habitats, compact soil, and alter local hydrology, contributing to degradation.

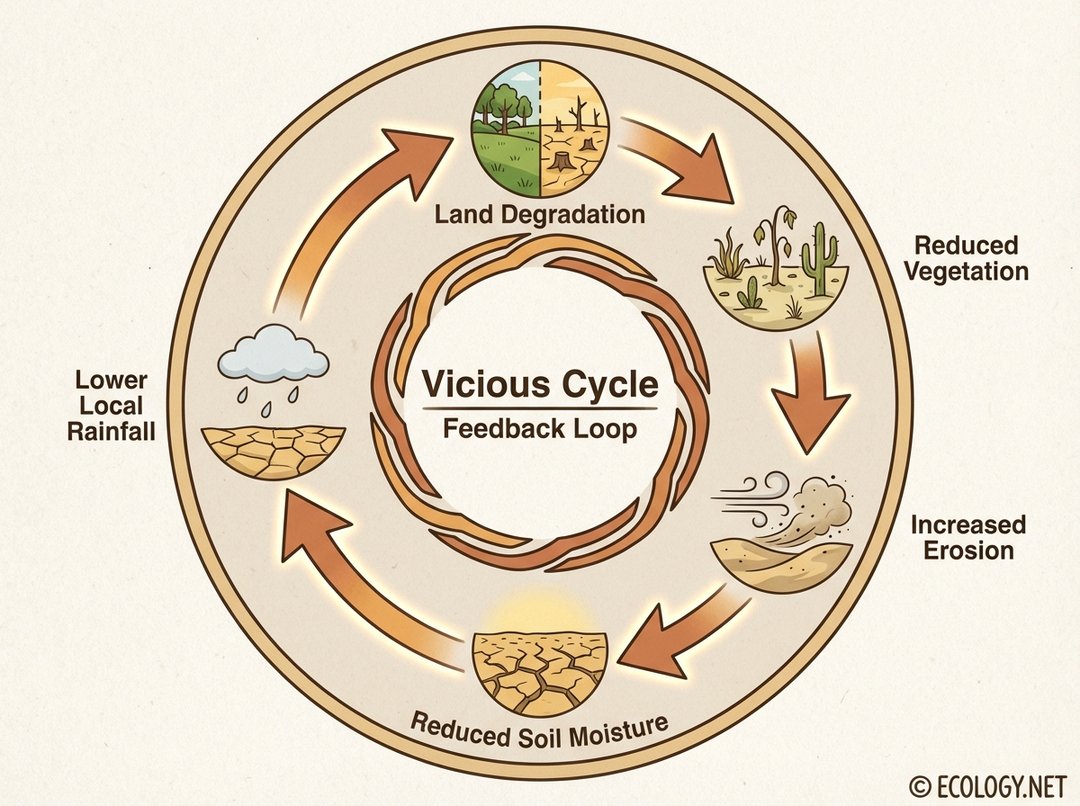

The Vicious Cycle: How Desertification Feeds Itself

One of the most insidious aspects of desertification is its self-reinforcing nature. Once the process begins, it often creates a feedback loop, where initial degradation triggers a cascade of environmental changes that further accelerate the problem. This makes it incredibly difficult to reverse.

The cycle often unfolds as follows:

- Land Degradation: The initial loss of soil quality and vegetation cover due to human activities or drought.

- Reduced Vegetation: As land degrades, fewer plants can grow. This means less organic matter is returned to the soil, and less plant cover protects the surface.

- Increased Erosion: With less vegetation to hold it in place, the soil becomes highly vulnerable to wind and water erosion. Precious topsoil, rich in nutrients, is blown or washed away.

- Reduced Soil Moisture: Eroded soil loses its capacity to absorb and retain water. Rainwater runs off quickly, taking more soil with it, rather than soaking in. This leads to drier conditions, even if rainfall amounts remain the same.

- Lower Local Rainfall: Reduced vegetation cover can also impact local climate. Plants release moisture into the atmosphere through transpiration, contributing to cloud formation and rainfall. A significant reduction in vegetation can lead to a decrease in local rainfall, exacerbating drought conditions.

- Back to Land Degradation: The drier, more eroded, and less fertile land becomes even less capable of supporting vegetation, completing the vicious cycle and intensifying the initial land degradation.

This feedback loop highlights why early intervention and sustainable land management are crucial to breaking the cycle before it becomes irreversible.

The Far-Reaching Consequences: Why Should We Care?

The impacts of desertification extend far beyond the immediate degraded areas, creating a ripple effect across environmental, social, and economic spheres.

Environmental Impacts:

- Biodiversity Loss: As habitats are destroyed and ecosystems degrade, countless species of plants and animals lose their homes, leading to a decline in biodiversity.

- Increased Dust Storms: Barren, eroded land is a prime source for dust. These storms can travel thousands of kilometers, impacting air quality, human health, and even contributing to glacier melt by depositing dark particles on ice.

- Water Scarcity: Desertified lands have reduced water retention capacity, leading to lower groundwater levels and diminished surface water sources, intensifying water scarcity for both human and ecological needs.

- Reduced Carbon Sequestration: Healthy soils and vegetation are significant carbon sinks. Desertification releases stored carbon into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change, while simultaneously reducing the land’s capacity to absorb future emissions.

Socio-Economic Impacts:

- Food Insecurity and Poverty: The loss of productive land directly impacts agricultural yields, leading to food shortages, malnutrition, and increased poverty, especially for communities reliant on subsistence farming.

- Forced Migration: When land can no longer support livelihoods, people are often forced to abandon their homes and migrate to other areas, often leading to increased pressure on resources in destination regions and potential social unrest.

- Conflict: Competition over dwindling resources, such as fertile land and water, can escalate into local or regional conflicts.

- Economic Losses: Desertification costs billions of dollars annually in lost agricultural production, ecosystem services, and the expenses associated with mitigation and adaptation.

Turning the Tide: Solutions and Prevention

Despite the daunting nature of desertification, it is not an irreversible process. Through concerted efforts and the implementation of sustainable practices, land can be restored and further degradation prevented. The key lies in understanding the local context and empowering communities to manage their land wisely.

Sustainable Land Management Practices:

- Afforestation and Reforestation: Planting trees, especially native species, helps stabilize soil, improve water retention, create microclimates, and restore biodiversity. Initiatives like Africa’s Great Green Wall are ambitious examples.

- Sustainable Agriculture:

- Conservation Tillage: Minimizing plowing to keep soil structure intact and organic matter on the surface.

- Crop Rotation and Diversification: Varying crops to maintain soil fertility and break pest cycles.

- Terracing and Contour Plowing: Techniques that reduce water runoff and soil erosion on slopes.

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees and shrubs into agricultural landscapes to enhance productivity and ecological benefits.

- Improved Irrigation Techniques:

- Drip Irrigation: Delivers water directly to plant roots, minimizing evaporation and water waste.

- Efficient Water Management: Monitoring soil moisture and weather to irrigate only when necessary.

- Salinity Management: Implementing proper drainage and using salt-tolerant crops where appropriate.

- Rotational Grazing: Managing livestock movement to allow pastures to recover, preventing overgrazing in any single area. This mimics natural grazing patterns and promotes healthier grasslands.

- Soil Conservation: Techniques like constructing gabions (stone-filled wire cages) or planting hedgerows to slow down water flow and trap eroded soil.

Policy, Research, and International Cooperation:

- Land Use Planning: Developing comprehensive plans that consider ecological limits and sustainable resource allocation.

- Policy Support: Governments can implement policies that incentivize sustainable practices and penalize destructive ones.

- Research and Innovation: Developing drought-resistant crops, improved soil management techniques, and better monitoring systems.

- International Agreements: The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) provides a global framework for addressing the issue, fostering cooperation and knowledge sharing among nations.

Empowering Local Communities:

Local communities, often the most affected, are also key to the solutions. Their traditional knowledge, combined with scientific approaches, can lead to effective and culturally appropriate land management strategies. Education and capacity building are vital for successful long-term interventions.

A Future Where Land Thrives

Desertification is a formidable challenge, intricately linked to climate change, food security, and human well-being. It is a stark reminder of our interconnectedness with the natural world and the profound impact our actions have on the planet. However, it is not a hopeless battle. By understanding its causes, recognizing its vicious cycles, and implementing sustainable land management practices, we can restore degraded lands, protect vulnerable ecosystems, and build a more resilient future. The health of our land is the foundation of our civilization, and by nurturing it, we secure a thriving future for all.