Unveiling the Wonders of Ecosystems: Earth’s Interconnected Life Support Systems

Imagine a bustling city, not of concrete and steel, but of living organisms and natural elements, all working together in a delicate, intricate dance. This is an ecosystem: a fundamental unit of nature where living things interact with each other and with their nonliving environment. From the smallest pond to the vastest ocean, from a patch of forest to an urban park, ecosystems are everywhere, shaping the very fabric of our planet and sustaining all life within them. Understanding ecosystems is not just for scientists; it is key to appreciating the profound interconnectedness of life and the critical importance of preserving our natural world.

The Core Components: Biotic and Abiotic Factors

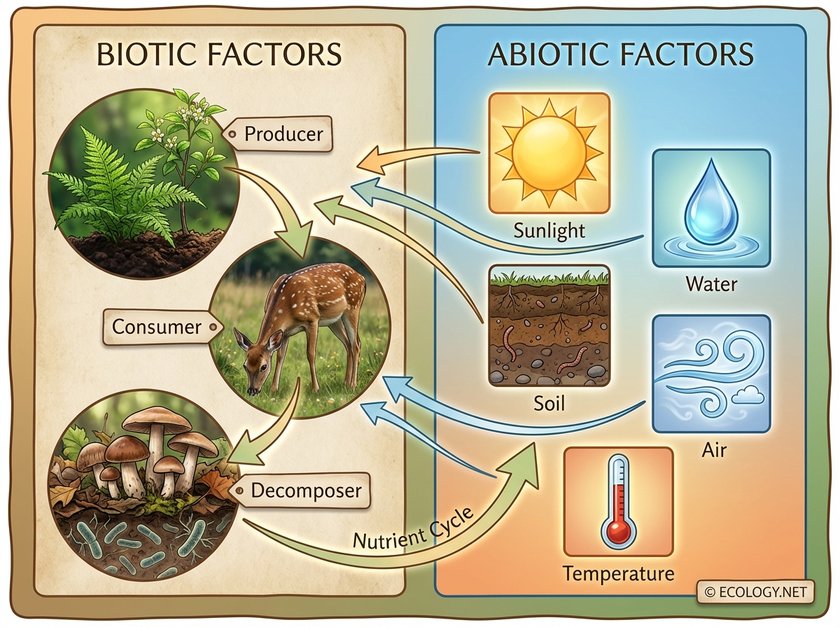

Every ecosystem, regardless of its size or location, is built upon two fundamental types of components: biotic and abiotic factors. These elements are in constant interaction, creating the unique character and function of each natural community.

Biotic factors are all the living or once-living parts of an ecosystem. Think of the vibrant tapestry of life:

- Producers: These are the foundation of nearly every ecosystem. Primarily green plants, algae, and some bacteria, producers create their own food, usually through photosynthesis, converting sunlight into energy. They are the primary source of energy for all other life forms. For example, a towering oak tree in a forest or microscopic phytoplankton in the ocean are producers.

- Consumers: Organisms that obtain energy by feeding on other organisms. Consumers are categorized by what they eat:

- Herbivores: Plant eaters, such as a deer grazing on leaves or a caterpillar munching on a leaf.

- Carnivores: Meat eaters, like a wolf hunting a deer or a hawk preying on a mouse.

- Omnivores: Eaters of both plants and animals, including bears foraging for berries and fish, or humans enjoying a varied diet.

- Decomposers: The unsung heroes of the ecosystem, primarily bacteria and fungi. They break down dead organic matter, returning vital nutrients to the soil or water, making them available for producers to use again. Without decomposers, ecosystems would quickly be buried in waste and run out of essential nutrients. Think of mushrooms sprouting from a fallen log or bacteria in the soil breaking down a dead leaf.

Abiotic factors are the nonliving physical and chemical elements that influence an ecosystem. These are the environmental conditions that dictate where and how life can thrive:

- Sunlight: The ultimate energy source for most ecosystems, driving photosynthesis.

- Water: Essential for all life processes, from plant growth to animal hydration. Its availability dictates the type of ecosystem, from deserts to rainforests.

- Soil: Provides physical support for plants and is a reservoir for water and nutrients. Its composition and fertility are crucial.

- Air: Supplies gases vital for life, such as oxygen for respiration and carbon dioxide for photosynthesis.

- Temperature: Influences metabolic rates and the distribution of species. Organisms have specific temperature ranges they can tolerate.

- Nutrients: Minerals and chemical elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, essential for growth and development.

The interplay between biotic and abiotic factors is constant. A plant (biotic) uses sunlight, water, and soil (abiotic) to grow. A deer (biotic) drinks water (abiotic) and eats plants (biotic). Decomposers (biotic) return nutrients to the soil (abiotic) from dead organisms. This intricate web of interactions defines the health and stability of an ecosystem.

Energy Flow: The Food Chain and Food Web

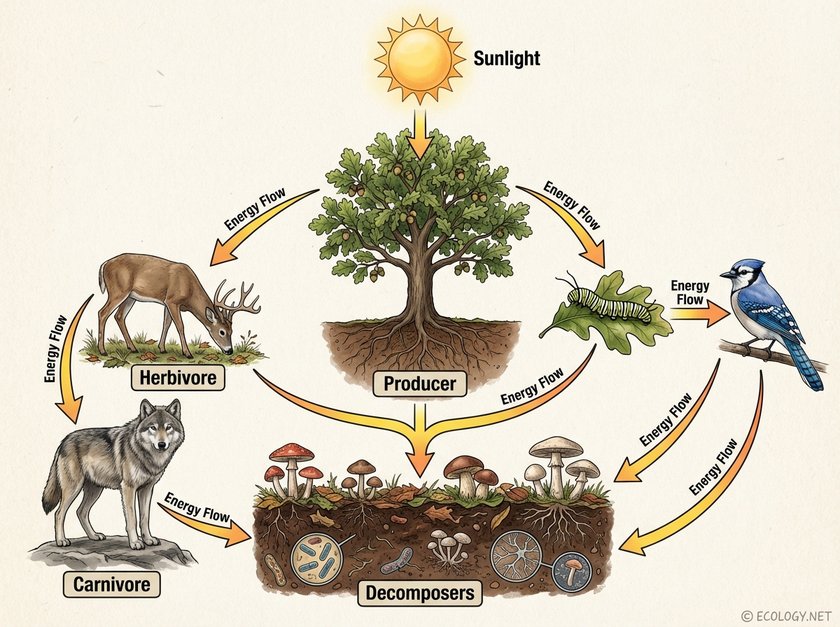

Life requires energy, and within an ecosystem, energy flows in a specific direction, typically starting from the sun. This transfer of energy is visualized through food chains and, more comprehensively, food webs.

A food chain illustrates a single pathway of energy flow. For example:

Sunlight → Grass → Rabbit → Fox

Here, the grass is the producer, the rabbit is a primary consumer (herbivore), and the fox is a secondary consumer (carnivore).

However, nature is rarely so simple. Most organisms eat, and are eaten by, multiple different species. This complex network of feeding relationships is called a food web. It shows how energy flows through an entire ecosystem, highlighting the interconnectedness of its inhabitants.

- Energy begins with the sun, captured by producers like plants (e.g., an oak tree).

- Herbivores (primary consumers) feed on these producers (e.g., a deer eating oak leaves, or a caterpillar eating leaves).

- Carnivores (secondary consumers) then feed on the herbivores (e.g., a wolf hunting a deer, or a bird eating a caterpillar).

- Top predators (tertiary consumers) might feed on other carnivores.

- Crucially, when any organism dies, or produces waste, decomposers (like mushrooms and bacteria) break down the organic matter, returning nutrients to the soil, thus completing the cycle and making those nutrients available for producers once more.

The arrows in a food web always point in the direction of energy flow, from the organism being eaten to the organism that eats it. This intricate web demonstrates that the removal or decline of one species can have ripple effects throughout the entire ecosystem, impacting many other species that rely on it for food or are preyed upon by it.

Nutrient Cycling: The Circle of Life

While energy flows through an ecosystem in one direction, nutrients cycle. Unlike energy, which is largely lost as heat at each trophic level, essential chemical elements like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus are continuously reused. These biogeochemical cycles are fundamental to sustaining life.

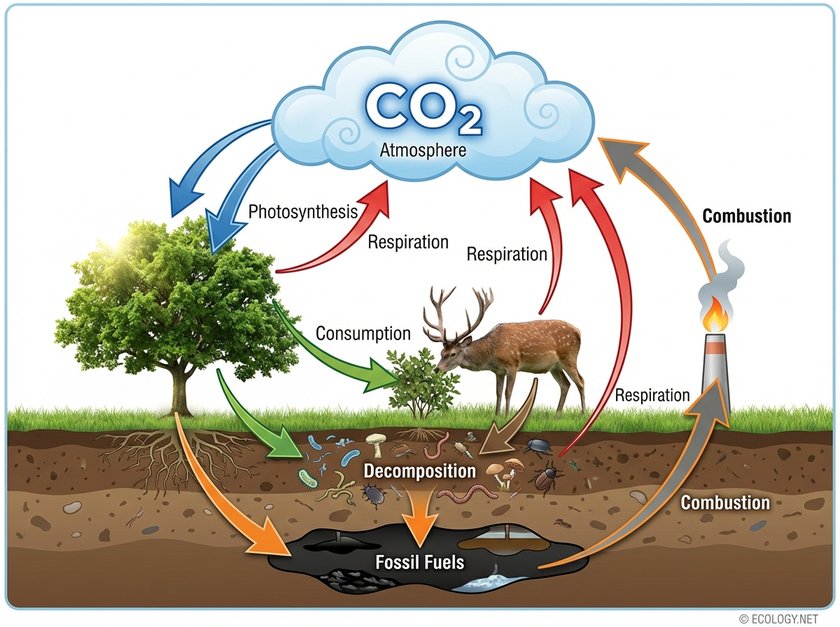

Let us explore one of the most vital cycles: the Carbon Cycle.

Carbon is the backbone of all organic molecules and a major component of Earth’s atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2). The carbon cycle describes its movement through the atmosphere, oceans, land, and living organisms:

- Photosynthesis: Plants (producers) absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and use sunlight to convert it into organic compounds (sugars), storing carbon in their tissues. This is how carbon enters the living world.

- Consumption: Animals (consumers) obtain carbon by eating plants or other animals. The carbon then becomes part of their bodies.

- Respiration: Both plants and animals release CO2 back into the atmosphere through cellular respiration, the process of breaking down food for energy.

- Decomposition: When plants and animals die, decomposers break down their organic matter, releasing carbon back into the soil and atmosphere.

- Fossil Fuels: Over millions of years, under specific conditions of heat and pressure, undecomposed organic matter can be transformed into fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas, storing vast amounts of carbon underground.

- Combustion: When humans burn fossil fuels for energy, or when natural events like forest fires occur, large amounts of stored carbon are rapidly released back into the atmosphere as CO2.

Other crucial cycles include the Nitrogen Cycle, which is essential for proteins and nucleic acids, and the Water Cycle, which moves water through evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. These cycles are not isolated; they are interconnected, demonstrating the holistic nature of ecosystem function.

Diverse Worlds: Types of Ecosystems

Ecosystems are incredibly diverse, ranging in size and characteristics. They can be broadly categorized into terrestrial (land based) and aquatic (water based) ecosystems.

Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Forests: Characterized by dense tree cover, such as tropical rainforests with their incredible biodiversity, temperate deciduous forests with seasonal changes, or boreal forests (taiga) adapted to cold climates.

- Grasslands: Dominated by grasses, like the African savannas with their large grazing animals, or the North American prairies.

- Deserts: Arid regions with sparse vegetation and specialized animals adapted to extreme dryness and temperature fluctuations, such as the Sahara or the Sonoran Desert.

- Tundra: Cold, treeless regions found in the Arctic and on high mountains, characterized by permafrost and low-growing vegetation.

Aquatic Ecosystems

- Freshwater Ecosystems:

- Lakes and Ponds: Standing bodies of water, varying in size and depth, supporting diverse fish, insect, and plant life.

- Rivers and Streams: Flowing water systems, often with distinct zones from source to mouth, influencing the types of organisms that can thrive.

- Wetlands: Areas where water covers the soil or is present either at or near the surface of the soil all year or for varying periods during the year, including marshes, swamps, and bogs, which are critical habitats and natural filters.

- Marine Ecosystems:

- Oceans: The largest ecosystems, encompassing vast open waters, deep sea trenches, and coastal zones, home to an immense array of life from microscopic plankton to colossal whales.

- Coral Reefs: Underwater structures built by colonies of tiny animals, incredibly biodiverse and often called the “rainforests of the sea.”

- Estuaries: Areas where freshwater rivers meet the ocean, creating unique brackish water environments that are highly productive nurseries for many marine species.

Ecosystem Services: Why They Matter to Us

Beyond their intrinsic value, ecosystems provide invaluable “ecosystem services” that are absolutely essential for human well being and survival. These are the benefits that nature provides to people, often without us even realizing it.

- Provisioning Services: The products we obtain from ecosystems.

- Food (crops, livestock, fish)

- Freshwater

- Timber and fiber

- Medicinal plants

- Regulating Services: The benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes.

- Climate regulation (carbon sequestration by forests)

- Flood regulation (wetlands absorbing excess water)

- Disease regulation (biodiversity can limit disease spread)

- Water purification (wetlands and forests filter pollutants)

- Air purification (plants remove pollutants)

- Pollination (insects and animals pollinating crops)

- Cultural Services: Nonmaterial benefits people obtain from ecosystems.

- Recreational opportunities (hiking, fishing, birdwatching)

- Spiritual enrichment and aesthetic beauty

- Educational and scientific inspiration

- Supporting Services: Services necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services.

- Nutrient cycling

- Soil formation

- Primary production (photosynthesis)

Recognizing these services highlights our profound dependence on healthy, functioning ecosystems.

Ecosystem Dynamics and Resilience

Ecosystems are not static; they are dynamic entities constantly undergoing change. This change can be gradual or sudden, natural or human induced.

Ecological Succession

This is the process by which the structure of a biological community evolves over time. It can be:

- Primary Succession: Occurs in an area devoid of life and soil, such as newly formed volcanic islands or bare rock exposed by a retreating glacier. Pioneer species like lichens and mosses colonize first, slowly building soil, allowing other plants to grow.

- Secondary Succession: Occurs in areas where a community has been removed but the soil remains, such as after a forest fire, logging, or an abandoned agricultural field. This process is generally faster because the soil and some seeds are already present.

Succession eventually leads to a more stable, mature community, though disturbances can always reset the process.

Disturbance and Resilience

A disturbance is an event that causes a significant change in an ecosystem, such as a wildfire, flood, hurricane, or human logging. While disturbances can be destructive, they are also natural processes that can create new opportunities for species and maintain biodiversity.

Ecosystem resilience is the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks. A resilient ecosystem can bounce back from a disturbance, perhaps returning to its original state or shifting to a new, stable state. Biodiversity often plays a key role in resilience, as a greater variety of species can offer more functional redundancy and adaptive capacity.

Threats to Ecosystems and the Call for Conservation

Despite their resilience, ecosystems worldwide face unprecedented threats, largely driven by human activities. These threats jeopardize the very services that sustain us.

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Deforestation for agriculture, urbanization, and infrastructure development destroy natural habitats, leading to species extinction and reduced biodiversity.

- Pollution: Air, water, and soil pollution from industrial activities, agriculture, and waste disposal contaminate ecosystems, harming organisms and disrupting natural processes.

- Climate Change: Human induced emissions of greenhouse gases are altering global temperatures and weather patterns, leading to sea level rise, extreme weather events, and shifts in species distribution, pushing many ecosystems beyond their adaptive capacity.

- Overexploitation: Unsustainable fishing, hunting, and harvesting of natural resources deplete populations and can lead to ecosystem collapse.

- Invasive Species: Introduction of non native species can outcompete native organisms, disrupt food webs, and alter ecosystem structure.

The urgent need for conservation is clear. Protecting ecosystems involves a range of strategies, from establishing protected areas and restoring degraded habitats to promoting sustainable resource management, reducing pollution, and mitigating climate change. It requires a global effort and a fundamental shift in how humanity interacts with the natural world.

Conclusion: Our Place in the Web of Life

Ecosystems are not just abstract scientific concepts; they are the living, breathing systems that make our planet habitable. They are intricate webs of life, where every component, living and nonliving, plays a vital role in the grand dance of energy flow and nutrient cycling. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every organism is connected, and every action has a consequence. By understanding, appreciating, and actively protecting these incredible natural systems, we ensure not only the survival of countless species but also the health and prosperity of humanity itself. Our future is inextricably linked to the health of our planet’s ecosystems.