Imagine a landscape where the ground beneath your feet is permanently frozen, where trees cannot grow, and where life persists against incredible odds. This is the tundra, one of Earth’s most unique and resilient biomes. Often perceived as barren, the tundra is in fact a vibrant ecosystem, teeming with specialized life forms that have mastered survival in extreme cold and short growing seasons. Understanding the tundra offers a profound insight into ecological adaptation and the delicate balance of our planet’s climate.

What is Tundra? The Frozen Foundation

At its core, the tundra is defined by its distinctive climate and geological features. The word “tundra” itself originates from the Kildin Sami word “tūndâr,” meaning “treeless plain.” This treeless characteristic is not merely a coincidence; it is a direct consequence of the most defining feature of this biome: permafrost.

The Role of Permafrost

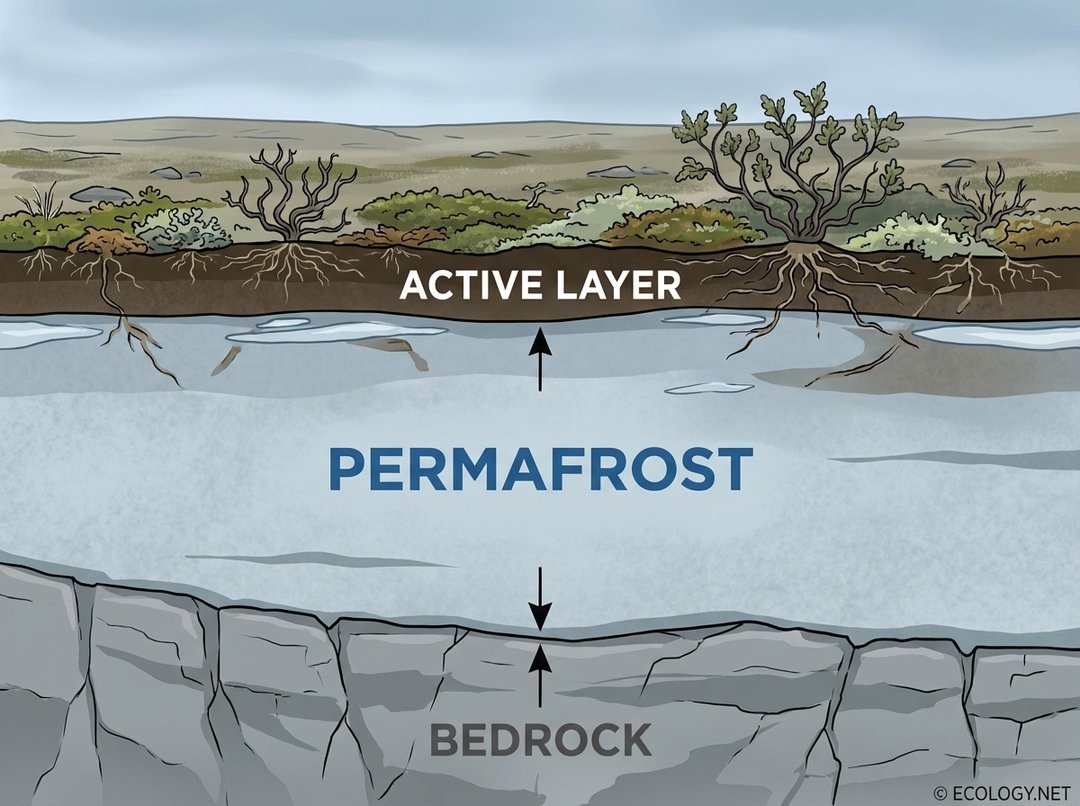

Permafrost is ground, including rock or soil, that remains completely frozen for at least two consecutive years. In many tundra regions, permafrost can extend hundreds of meters deep. Above this permanently frozen layer lies the “active layer,” a thin surface layer of soil that thaws during the brief summer months and refreezes in winter. This seasonal thawing allows for plant growth, but its shallow depth and the underlying permafrost prevent the establishment of deep-rooted plants like trees.

The presence of permafrost creates a unique hydrological environment. When the active layer thaws, water cannot drain downwards due to the impermeable permafrost beneath. This leads to widespread waterlogging, forming numerous shallow lakes, ponds, and bogs across the landscape, even in areas with relatively low precipitation. These saturated conditions, combined with low temperatures, significantly slow down decomposition rates, leading to the accumulation of organic matter.

A Climate of Extremes

Tundra regions experience extremely cold temperatures, particularly in winter, with average annual temperatures often below freezing. Summers are short and cool, typically lasting only 6 to 10 weeks, with temperatures rarely exceeding 10 degrees Celsius. Precipitation is generally low, often falling as snow, making the tundra technically a cold desert. However, the lack of drainage due to permafrost ensures that moisture is retained near the surface, supporting the characteristic low-growing vegetation.

Types of Tundra: A Global Perspective

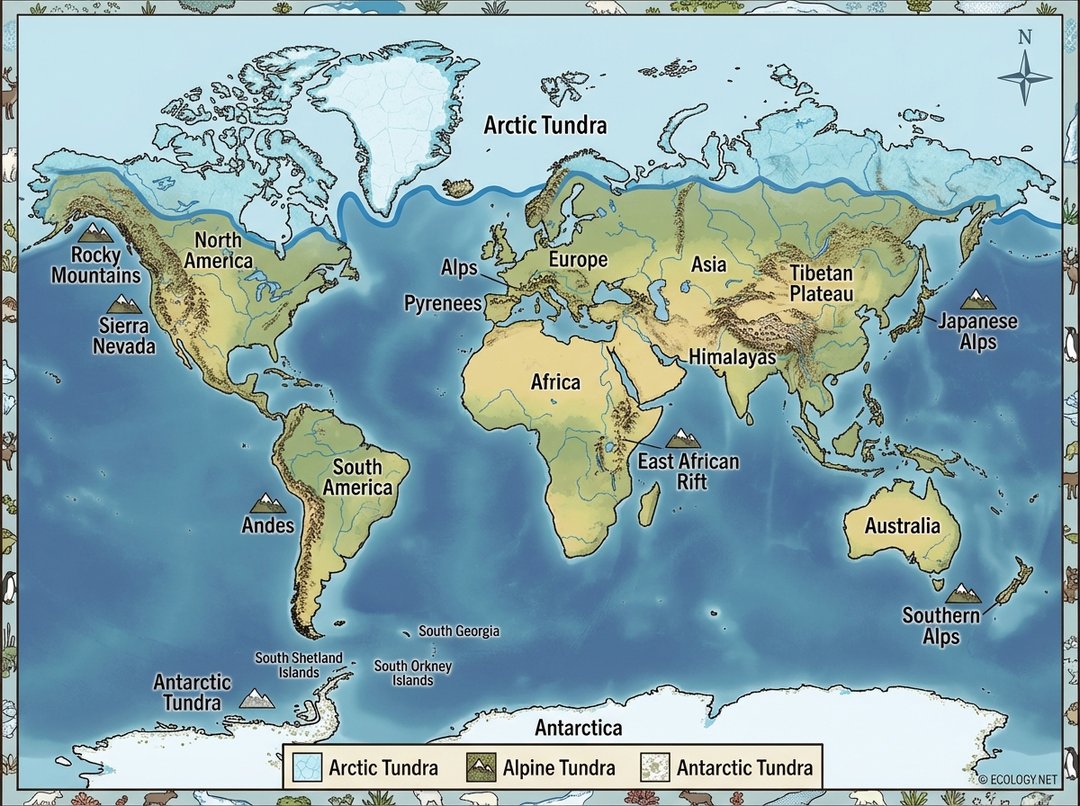

While sharing common characteristics, tundra ecosystems are found in different geographical contexts, leading to three primary classifications:

Arctic Tundra

The most extensive type of tundra, Arctic tundra, encircles the North Pole, stretching across northern North America, Europe, and Asia. It is characterized by:

- Vast, treeless plains.

- Extensive permafrost.

- Long, dark, extremely cold winters.

- Short, cool summers with continuous daylight (midnight sun).

- Dominant vegetation includes mosses, lichens, sedges, grasses, and dwarf shrubs like willow and birch.

- Iconic animals include caribou, musk oxen, Arctic foxes, polar bears, and numerous migratory birds.

Alpine Tundra

Unlike Arctic tundra, Alpine tundra is found on high mountain ranges across the globe, above the treeline and below the permanent snow line. It shares many characteristics with Arctic tundra but differs in key ways:

- No underlying permafrost is required, though it can occur at very high altitudes.

- Temperatures fluctuate more widely, with intense solar radiation during the day and rapid cooling at night.

- Soils are generally well-drained due to topography, leading to less waterlogging than Arctic tundra.

- Vegetation includes cushion plants, grasses, sedges, and small flowering plants adapted to strong winds and thin air.

- Animals include mountain goats, marmots, pikas, and various raptors, often with adaptations for rocky terrain.

Antarctic Tundra

This is the least common type of tundra, primarily found on the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby islands. The vast majority of Antarctica is covered by ice sheets, leaving little exposed land for tundra development. Key features include:

- Extremely harsh conditions, even colder and windier than much of the Arctic.

- Limited biodiversity, with only two native flowering plants: Antarctic hair grass and Antarctic pearlwort.

- Dominant plant life consists of mosses, lichens, and algae.

- Animal life is largely marine-based, including penguins, seals, and seabirds, which rely on the surrounding ocean for food.

Life in the Frozen Realm: Adaptations and Biodiversity

Despite the challenging conditions, tundra ecosystems support a surprising array of life, each species exhibiting remarkable adaptations to survive the cold, wind, and short growing season.

Plant Adaptations

Tundra plants are masters of survival, employing various strategies:

- Low Growth Form: Most plants grow close to the ground, forming mats or cushions. This protects them from strong winds, traps heat, and allows them to be insulated by snow cover in winter.

- Shallow Root Systems: Due to the active layer’s limited depth and the presence of permafrost, plants have shallow, spreading root systems.

- Perennial Life Cycles: Many tundra plants are perennials, meaning they live for more than two years. They allocate energy to root growth and storage, allowing them to quickly resume growth when conditions are favorable.

- Rapid Reproduction: Some plants flower and produce seeds quickly during the brief summer. Others reproduce vegetatively, spreading through rhizomes or runners.

- Dark Pigmentation: Some plants have dark leaves or stems to absorb more solar radiation, helping them warm up faster.

- Hairy Stems and Leaves: A furry coating can help trap heat and reduce water loss.

Examples of tundra flora include Arctic poppies, cotton grass, various mosses and lichens, dwarf willows, and cranberries.

Animal Adaptations

Tundra animals have evolved ingenious ways to cope with the cold and scarcity of food:

- Thick Insulation: Many animals possess dense fur or feathers, often with a thick layer of subcutaneous fat, to provide insulation against the cold. For example, the Arctic fox’s winter coat is incredibly thick.

- Hibernation or Torpor: Some animals, like marmots and ground squirrels, hibernate through the winter, slowing their metabolic rate to conserve energy.

- Migration: Many bird species, such as various geese and shorebirds, migrate to the tundra for breeding during the summer months, taking advantage of the abundant insects and plant growth, then returning to warmer climates for winter.

- Camouflage: Animals like the Arctic fox and ptarmigan change their fur or feather color seasonally to blend with their surroundings, white in winter and brown/grey in summer, providing camouflage from predators and prey.

- Specialized Diets: Herbivores like caribou and musk oxen are adapted to digest tough tundra vegetation, while predators like wolves and polar bears are apex hunters in their respective niches.

- Short Appendages: Animals often have smaller ears, tails, and limbs to minimize heat loss through exposed surfaces.

Beyond the Arctic fox, other notable tundra animals include lemmings, voles, snowy owls, and various species of insects like mosquitoes and black flies, which emerge in vast numbers during the summer.

Ecosystem Dynamics: Cycles and Interactions

The tundra ecosystem operates on a slower, more deliberate pace compared to temperate or tropical biomes. This is largely due to the cold temperatures and the presence of permafrost, which influence nutrient cycling, water dynamics, and food web structures.

Slow Nutrient Cycling

Decomposition is a critical process for returning nutrients to the soil. In the tundra, low temperatures and waterlogged soils significantly inhibit the activity of decomposers like bacteria and fungi. This leads to a slow rate of nutrient cycling and the accumulation of organic matter, often in the form of peat. While this means nutrients are not readily available, the plants have adapted to efficiently absorb what is present, and many form symbiotic relationships with fungi (mycorrhizae) to enhance nutrient uptake.

Water Dynamics

Despite low precipitation, the tundra can be surprisingly wet. The impermeable permafrost acts as a barrier, preventing meltwater from percolating deep into the ground. This results in the formation of extensive wetlands, bogs, and shallow lakes during the summer thaw. These water bodies are crucial habitats for insects and migratory birds, and they play a significant role in the regional water balance. The freeze-thaw cycles also contribute to unique landforms such as patterned ground, solifluction lobes, and pingos.

Food Webs

Tundra food webs are relatively simple but robust. Primary producers consist of mosses, lichens, grasses, sedges, and dwarf shrubs. These are consumed by herbivores such as lemmings, voles, caribou, and musk oxen. These herbivores, in turn, become prey for predators like Arctic foxes, wolves, snowy owls, and various raptors. During the summer, insect populations explode, providing a vital food source for many bird species. The simplicity of the food web means that changes at one level can have significant impacts throughout the entire ecosystem.

Threats and Conservation: A Fragile Frontier

The tundra, while resilient, is also incredibly fragile and faces significant threats, primarily from climate change and human activities.

Climate Change and Permafrost Thaw

The tundra is warming at a rate faster than almost any other biome on Earth. This warming has profound implications, especially for permafrost. As permafrost thaws, several critical issues arise:

- Release of Greenhouse Gases: Permafrost contains vast stores of ancient organic carbon. When it thaws, microbes become active and decompose this organic matter, releasing potent greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane into the atmosphere. This creates a positive feedback loop, accelerating global warming.

- Changes in Hydrology: Thawing permafrost can lead to ground subsidence, creating “thermokarst” lakes and altering drainage patterns. This can dry out some areas while creating new wetlands in others, impacting plant and animal habitats.

- Erosion: Coastal tundra regions are particularly vulnerable to increased erosion as permafrost thaws and sea ice diminishes, exposing shorelines to stronger wave action.

- Vegetation Shifts: As temperatures rise, the treeline may advance northward into the tundra, altering habitats and potentially outcompeting native tundra vegetation.

Human Impact

Beyond climate change, human activities also pose threats:

- Resource Extraction: Tundra regions are rich in natural resources, including oil, natural gas, and minerals. Exploration and extraction activities can lead to habitat destruction, pollution, and disruption of wildlife migration routes.

- Pollution: Industrial pollution, often originating far from the tundra, can be carried by winds and deposited in these pristine environments, impacting sensitive ecosystems.

- Infrastructure Development: Roads, pipelines, and settlements built on permafrost can cause it to thaw, leading to structural instability and environmental damage.

- Tourism: While generally low-impact, increasing tourism can disturb wildlife and damage fragile vegetation if not managed responsibly.

Conservation Efforts

Protecting the tundra requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Mitigating Climate Change: Reducing global greenhouse gas emissions is paramount to slowing permafrost thaw and its cascading effects.

- Establishing Protected Areas: National parks, wildlife refuges, and other protected areas safeguard critical tundra habitats and their biodiversity.

- Sustainable Resource Management: Implementing strict environmental regulations and best practices for any resource extraction activities to minimize ecological impact.

- Research and Monitoring: Continued scientific research is essential to understand the complex changes occurring in tundra ecosystems and to inform effective conservation strategies.

- Indigenous Knowledge Integration: Incorporating the traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous communities, who have lived in harmony with the tundra for millennia, is crucial for sustainable management.

Conclusion

The tundra is far more than just a frozen wasteland; it is a testament to life’s tenacity and a critical component of Earth’s climate system. Its unique landscapes, specialized flora and fauna, and delicate ecological processes offer invaluable lessons in adaptation and resilience. As global temperatures continue to rise, the tundra stands as a stark reminder of the interconnectedness of our planet and the urgent need for concerted efforts to protect these fragile, yet profoundly beautiful, frozen frontiers for future generations.