Beneath our feet lies a hidden world, a complex and dynamic environment that is far more than just dirt. It is the foundation of terrestrial life, a living matrix that supports everything from towering trees to the smallest microbes. At the heart of this intricate system is a concept often overlooked but profoundly important: soil structure. Understanding soil structure is like peering into the architecture of the earth itself, revealing how its components are organized and why that organization dictates the health and productivity of our ecosystems.

Imagine soil not as a uniform mass, but as a bustling city, complete with buildings, roads, and open spaces. Soil structure refers to the arrangement of soil particles into stable units called aggregates. These aggregates, along with the spaces between them, create a complex network of pores that are essential for air, water, and root movement. It is this intricate arrangement that determines how well soil can perform its vital functions.

The Unseen Architecture: What is Soil Structure Made Of?

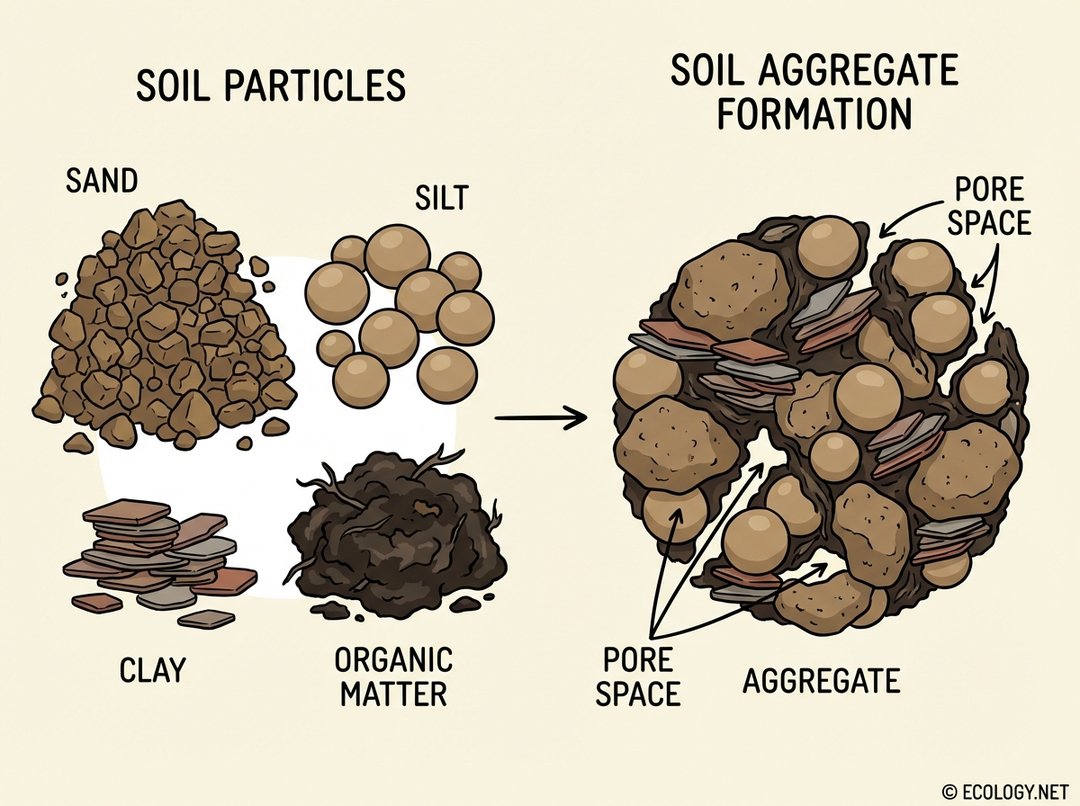

To truly grasp soil structure, we must first understand its fundamental building blocks. Soil is composed of four main ingredients:

- Mineral Particles: These are the weathered remnants of rocks, categorized by size.

- Sand: The largest particles, feeling gritty and providing good drainage.

- Silt: Medium-sized particles, feeling smooth and floury, often retaining water well.

- Clay: The smallest particles, feeling sticky when wet, with a high surface area that allows them to hold water and nutrients tightly.

- Organic Matter: Decomposed plant and animal residues, along with living organisms. This is the glue that binds mineral particles together, enriching the soil with nutrients and improving its water-holding capacity.

- Water: Essential for plant growth and microbial activity, filling some of the pore spaces.

- Air: Crucial for root respiration and the survival of beneficial soil organisms, occupying the remaining pore spaces.

These individual components do not simply lie haphazardly. Instead, they are bound together by various forces, including the sticky secretions of microbes, the fungal hyphae that weave through the soil, and the chemical attraction between clay particles and organic matter. This binding process forms larger, more stable units known as aggregates. The spaces between and within these aggregates are called pore spaces, and their size and connectivity are paramount.

The Master Builders: How Soil Structure Forms

The creation of soil aggregates is a fascinating interplay of physical, chemical, and biological forces. Think of it as a continuous construction project happening underground:

- Biological Activity: This is arguably the most significant driver.

- Plant Roots: As roots grow, they push through soil, creating channels and exuding sticky substances that bind particles.

- Microorganisms: Bacteria and fungi produce glues and gums that cement soil particles together. Fungal hyphae, in particular, act like microscopic nets, enmeshing particles into stable aggregates.

- Earthworms and Other Fauna: These soil engineers burrow through the soil, ingesting particles and excreting them as nutrient-rich casts, which are highly stable aggregates. Their tunnels also create vital macropores.

- Chemical Processes: Clay particles, with their negative charges, can attract positively charged ions and organic molecules, forming bridges that link particles. Organic matter itself acts as a powerful binding agent.

- Physical Processes: Cycles of wetting and drying, and freezing and thawing, can cause soil particles to expand and contract, leading to the formation of cracks and natural planes of weakness that eventually develop into aggregates.

A Gallery of Soil Structures: Different Shapes, Different Stories

Just as buildings come in various architectural styles, soil aggregates exhibit distinct shapes and sizes, each telling a story about the soil’s history, composition, and potential. Ecologists classify soil structure into several primary types:

- Granular Structure:

- Appearance: Small, spherical, crumb-like aggregates, often resembling breakfast cereal.

- Implication: Typically found in the topsoil (A horizon), rich in organic matter, and indicative of excellent aeration and water infiltration. This is often considered ideal for plant growth.

- Blocky Structure:

- Appearance: Irregular, cube-shaped aggregates, ranging from angular (sharp edges) to subangular (rounded edges).

- Implication: Common in subsoils (B horizon), especially in clay-rich soils. Provides moderate drainage and aeration. Angular blocky can indicate some compaction, while subangular blocky is generally more favorable.

- Platy Structure:

- Appearance: Flat, horizontal, plate-like aggregates stacked on top of each other.

- Implication: Often a sign of compaction, either natural (due to soil formation processes) or human-induced (from heavy machinery). This structure impedes water movement and root penetration, leading to poor drainage and aeration.

- Prismatic Structure:

- Appearance: Vertical, pillar-like aggregates with flat, distinct tops.

- Implication: Typically found in subsoils of arid and semi-arid regions, often associated with high clay content. Can restrict root growth horizontally but allows vertical water movement.

- Columnar Structure:

- Appearance: Similar to prismatic, but with rounded tops.

- Implication: Often found in soils with higher sodium content, which can disperse clay particles and lead to this specific shape.

- Massive (or Structureless):

- Appearance: A solid, uniform block of soil with no visible aggregates or natural planes of weakness.

- Implication: This is a highly undesirable structure, indicating severe compaction or very low organic matter. It severely restricts water infiltration, aeration, and root growth, making the soil very difficult to work with.

Why Does Soil Structure Matter? The Foundation of Life

The arrangement of soil particles into aggregates and the resulting pore spaces are not merely academic curiosities; they are fundamental to the soil’s ability to support life. Good soil structure is the bedrock of healthy ecosystems and productive agriculture.

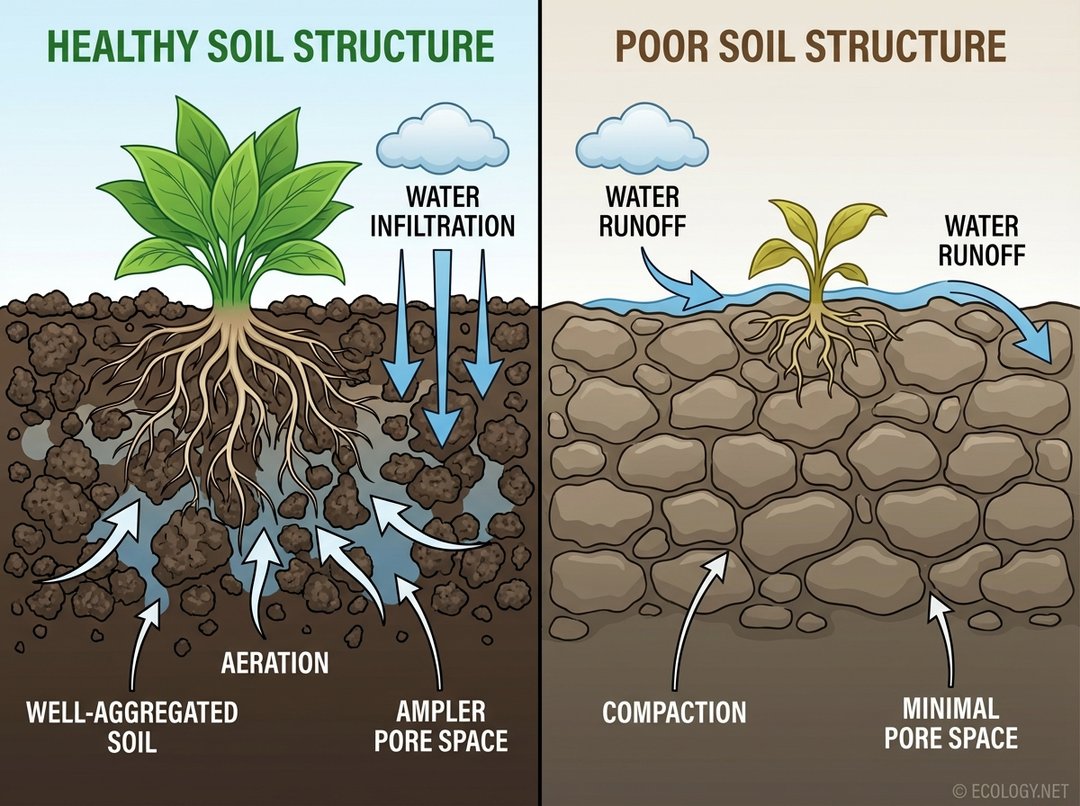

- Water Management: Well-structured soil acts like a sponge, readily absorbing rainfall and irrigation water. The large, interconnected pore spaces allow water to infiltrate deeply, reducing runoff and erosion. This stored water then becomes available to plants during dry periods. Conversely, poor structure leads to water pooling on the surface or running off, taking valuable topsoil with it.

- Aeration: Plant roots, like all living organisms, need oxygen to respire. The air-filled pore spaces in well-structured soil provide this vital oxygen, preventing anaerobic conditions that can harm roots and beneficial microbes.

- Root Penetration: Roots can easily navigate through the loose, aggregated soil, extending deep to access water and nutrients. In compacted soil, roots struggle to penetrate, remaining shallow and making plants more vulnerable to drought and nutrient deficiencies.

- Nutrient Cycling: The diverse habitats created by good structure support a thriving community of soil organisms, from bacteria and fungi to earthworms. These organisms are the engine of nutrient cycling, breaking down organic matter and making essential nutrients available to plants.

- Erosion Resistance: Stable aggregates are less susceptible to being dislodged by wind or water. This means less topsoil loss, preserving the most fertile layer of the soil.

The Dark Side: When Soil Structure Goes Wrong

The consequences of poor soil structure are far-reaching and detrimental. When aggregates break down, and pore spaces collapse, the soil becomes dense and compacted. This leads to a cascade of problems:

- Reduced Water Infiltration: Water struggles to penetrate the dense surface, leading to increased runoff, localized flooding, and reduced water availability for plants.

- Poor Aeration: Lack of air suffocates roots and beneficial aerobic microbes, favoring harmful anaerobic organisms. This can lead to root diseases and a buildup of toxic compounds.

- Stunted Root Growth: Roots cannot physically penetrate compacted layers, leading to shallow root systems that make plants less resilient to stress.

- Increased Erosion: Without stable aggregates, individual soil particles are easily carried away by wind and water, leading to significant loss of fertile topsoil.

- Nutrient Lock-up: Poor aeration and microbial activity can hinder nutrient cycling, making essential nutrients unavailable to plants even if they are present in the soil.

- Difficulty in Cultivation: Compacted soil is hard, requiring more energy and effort to till, often exacerbating the problem.

Cultivating Good Structure: Practical Steps for Soil Health

The good news is that soil structure is not static; it can be improved and maintained through thoughtful management practices. Whether you are a farmer, a gardener, or simply someone interested in ecological health, these strategies can make a significant difference:

- Add Organic Matter: This is perhaps the single most effective way to improve soil structure. Incorporate compost, well-rotted manure, cover crops, and mulches. Organic matter acts as a binding agent, feeds soil microbes, and improves water retention.

- Minimize Tillage: Excessive plowing and tilling disrupt existing aggregates, breaking down the delicate soil architecture. Practices like no-till or reduced-till farming help preserve structure, allowing natural processes to build stable aggregates.

- Avoid Compaction: Heavy machinery, livestock, and even foot traffic on wet soil can crush aggregates and collapse pore spaces. Use designated pathways, practice controlled traffic farming, and avoid working soil when it is saturated.

- Promote Biological Activity: Encourage earthworms by providing organic matter and minimizing disturbances. Support beneficial fungi and bacteria by reducing chemical inputs and maintaining a healthy soil food web.

- Plant Cover Crops: Growing non-cash crops like clover, rye, or vetch during fallow periods protects the soil surface, adds organic matter, and their roots help build structure.

- Proper Irrigation: Apply water slowly and deeply to allow for infiltration without causing surface crusting or runoff, which can damage aggregates.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Insights into Soil Structure Dynamics

For those delving deeper, the intricacies of soil structure offer even more fascinating insights. The stability of aggregates, for instance, is not uniform. Some aggregates are highly stable, resisting breakdown even under stress, while others are more fragile. Factors influencing aggregate stability include:

- Type of Organic Matter: Fresh, easily decomposable organic matter provides quick but temporary binding, while humified organic matter provides more long-term stability.

- Clay Mineralogy: Certain types of clay minerals, particularly those with high shrink-swell capacity, can contribute to aggregate formation through physical forces.

- Microbial Exudates: Specific compounds like glomalin, produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, are exceptionally powerful glues, significantly enhancing aggregate stability.

- Calcium and Magnesium: These divalent cations can bridge clay particles and organic matter, forming stable bonds.

The concept of “soil tilth” is also closely related to structure. Tilth describes the physical condition of the soil in relation to plant growth. A soil with good tilth is friable, meaning it crumbles easily, has good aeration, and allows for easy root penetration. It is a holistic assessment that encompasses structure, texture, and consistency.

Understanding these dynamics allows for more nuanced management. For example, in degraded soils, a multi-pronged approach combining organic matter addition, cover cropping, and minimal disturbance can gradually rebuild structure over several years. Monitoring aggregate stability through simple tests can provide valuable feedback on the effectiveness of management practices.

Conclusion

Soil structure is a silent hero, an invisible architect working tirelessly beneath our feet. It dictates how water moves, how air circulates, and how roots grow, ultimately determining the health and resilience of our plants and ecosystems. From the tiny grains of sand and clay to the complex aggregates they form, every component plays a crucial role in this intricate dance. By understanding and actively nurturing good soil structure, we are not just improving our gardens or farms; we are investing in the very foundation of life on Earth, ensuring a healthier, more productive future for all.