The Living Earth Beneath Our Feet: Unearthing the Wonders of Soil

Beneath every step we take, every tree that grows, and every crop that nourishes us, lies a world teeming with life and intricate processes: soil. Far from being mere inert dirt, soil is a dynamic, living ecosystem, a vital foundation for nearly all terrestrial life on Earth. It is a complex matrix, constantly forming, evolving, and performing indispensable services that sustain our planet. Understanding soil is not just for scientists or farmers, it is for everyone who breathes air, drinks water, and eats food.

What Exactly Is Soil? The Recipe for Life

To truly appreciate soil, we must first understand its fundamental composition. Imagine a finely tuned recipe, where each ingredient plays a crucial role. Soil is typically composed of five primary components, each contributing to its unique properties and functions.

Let us break down these essential ingredients:

- Mineral Particles: These are the weathered fragments of rocks and minerals, forming the bulk of the soil. They are categorized by size:

- Sand: Large, gritty particles that allow for good drainage and aeration.

- Silt: Medium-sized particles, feeling smooth and floury, which retain moisture better than sand.

- Clay: Tiny, plate-like particles that are sticky when wet and hard when dry. Clay is crucial for nutrient retention and water holding capacity.

The proportion of sand, silt, and clay determines the soil’s texture, influencing its ability to hold water and nutrients.

- Organic Matter: This dark, rich component is derived from decaying plant and animal remains. It includes everything from fresh litter to fully decomposed humus. Organic matter is the lifeblood of soil, improving its structure, increasing water retention, providing nutrients for plants, and fueling soil organisms. Think of it as the soil’s natural sponge and nutrient reservoir.

- Water: Held within the pore spaces between mineral particles and organic matter, water is essential for all life in the soil. It dissolves nutrients, making them available for plant uptake, and serves as a medium for countless chemical and biological reactions.

- Air: Just like water, air occupies the pore spaces in soil. It provides oxygen for plant roots and the vast array of soil organisms that respire, breaking down organic matter and releasing nutrients. Well-aerated soil is crucial for healthy root growth and microbial activity.

- Living Organisms: This is where soil truly comes alive. From microscopic bacteria and fungi to visible earthworms, insects, and plant roots, soil is a bustling metropolis of life. These organisms are the architects and engineers of soil, constantly working to decompose organic matter, cycle nutrients, create soil structure, and even protect plants from disease.

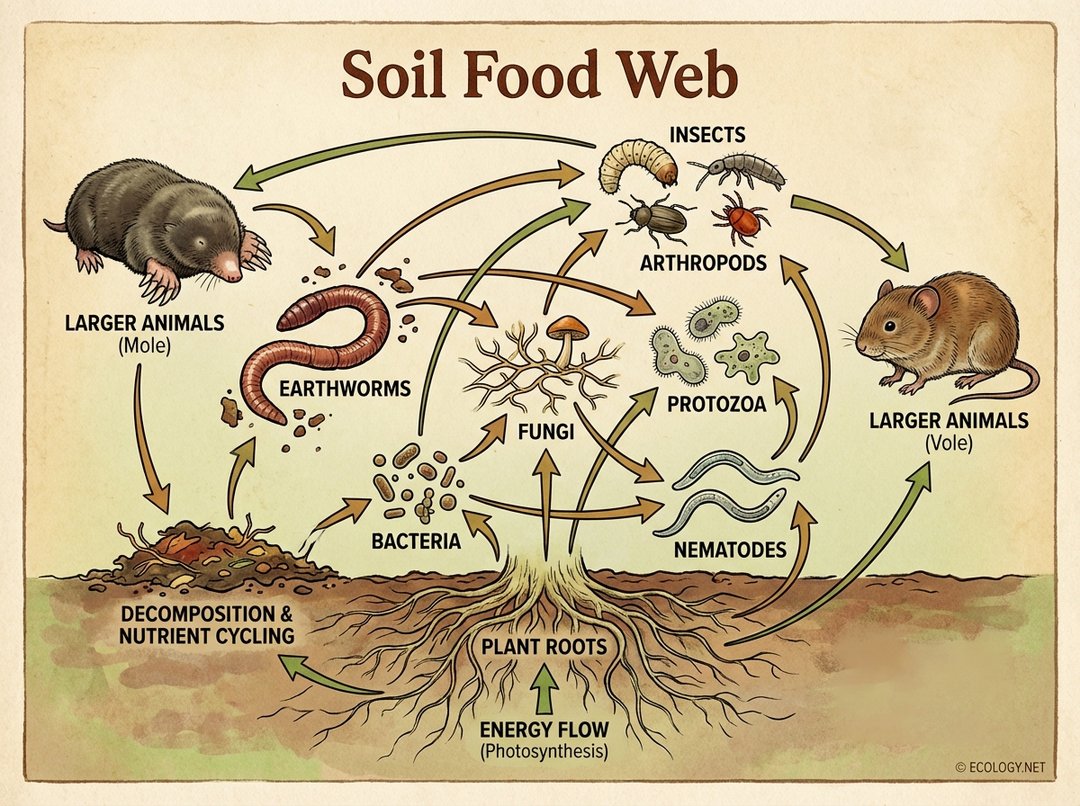

The Soil Food Web: Life Beneath the Surface

The living organisms within soil do not exist in isolation, they are intricately connected in a complex network known as the soil food web. This web illustrates the flow of energy and nutrients through different trophic levels, much like a terrestrial food web above ground. It is a testament to the incredible biodiversity hidden from plain sight.

At the base of this web are the primary producers, mainly plant roots, which release sugars and other compounds into the soil. These exudates feed a vast array of organisms:

- Bacteria and Fungi: These are the primary decomposers, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler forms. Bacteria are incredibly diverse, performing roles from nitrogen fixation to nutrient cycling. Fungi, with their extensive networks of hyphae, are crucial for decomposing tough materials like wood and connecting plants in mycorrhizal associations.

- Protozoa and Nematodes: These microscopic grazers feed on bacteria and fungi, releasing excess nutrients in a form that plants can readily absorb. Protozoa are single-celled organisms, while nematodes are tiny, unsegmented worms. Some nematodes are plant parasites, but many are beneficial, preying on other nematodes or bacteria.

- Arthropods and Earthworms: These larger organisms play vital roles as shredders, predators, and ecosystem engineers. Arthropods, such as mites, springtails, and insects, break down organic matter and aerate the soil. Earthworms are particularly important, ingesting soil and organic matter, mixing it, and creating tunnels that improve aeration and water infiltration. Their castings are rich in nutrients.

- Larger Animals: Moles, voles, and other burrowing animals also contribute to soil aeration and mixing, though their impact is more localized.

The soil food web is a continuous cycle of life, death, and decomposition, ensuring that nutrients are constantly recycled and made available for new growth. Without this intricate network, the fertility and health of our soils would rapidly decline.

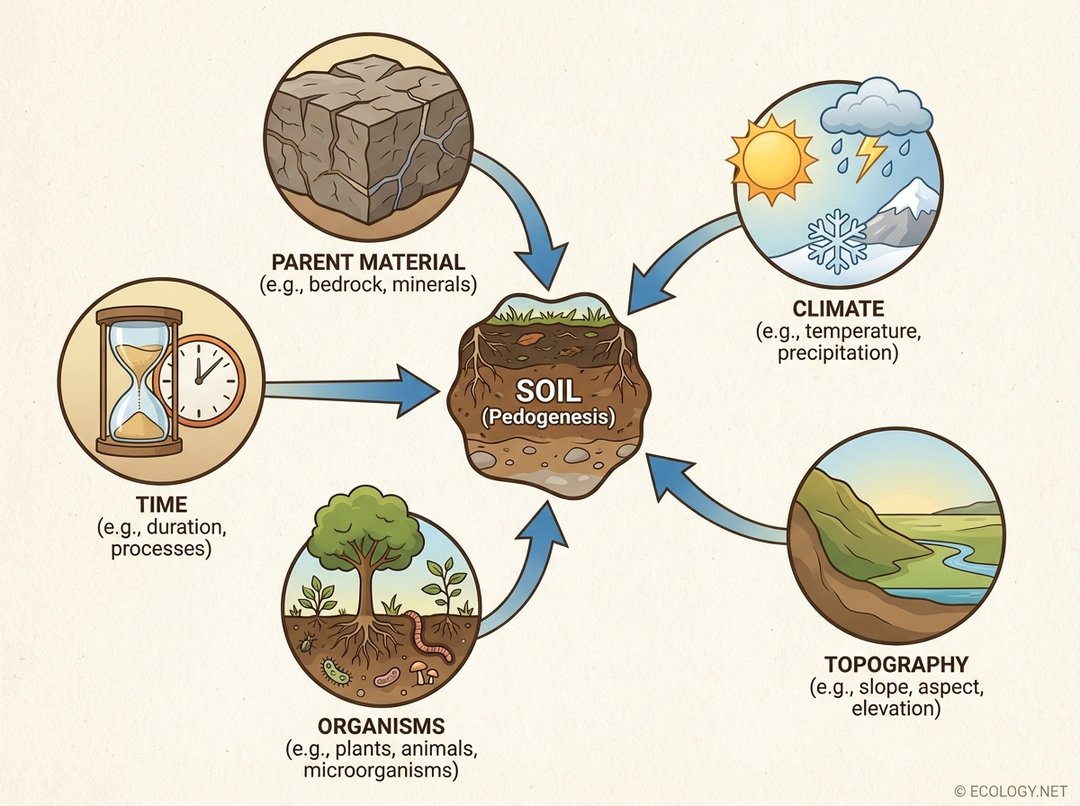

How Soil Forms: A Geological and Biological Tale

The creation of soil, a process known as pedogenesis, is not an overnight event. It is a slow, continuous interaction of geological, climatic, and biological forces that can take hundreds to thousands of years to form just a few centimeters of topsoil. Five key factors influence this remarkable transformation.

Let us explore these fundamental drivers of soil formation:

- Parent Material: This is the original geological material from which the soil develops. It can be bedrock, like granite or limestone, or unconsolidated sediments transported by wind (loess), water (alluvium), or glaciers (till). The parent material dictates the initial mineral composition and texture of the developing soil, influencing its nutrient content and drainage characteristics. For example, soils derived from limestone tend to be rich in calcium.

- Climate: Temperature and precipitation are powerful agents of weathering and decomposition.

- Temperature: Fluctuations cause physical weathering, breaking down rocks. Higher temperatures also accelerate chemical reactions and biological activity.

- Precipitation: Water is crucial for chemical weathering, dissolving minerals, and transporting soil particles. Abundant rainfall can leach nutrients, while arid climates may lead to salt accumulation.

Climate also influences the type of vegetation that grows, which in turn affects organic matter input.

- Topography (Relief): The shape of the land, including its slope, elevation, and aspect (direction it faces), significantly impacts soil formation.

- Slope: Steep slopes often have thinner soils due to erosion, while flatter areas accumulate deeper soils.

- Aspect: Slopes facing the sun may be warmer and drier, affecting vegetation and moisture levels.

- Drainage: Low-lying areas can accumulate water, leading to waterlogged soils with distinct characteristics.

Gravity plays a major role in how water moves through and across the landscape, influencing soil development.

- Organisms: Living organisms, from microbes to large animals and plants, are indispensable soil builders.

- Plants: Their roots break up parent material, add organic matter when they die, and extract nutrients from deeper layers.

- Animals: Earthworms, ants, termites, and burrowing mammals mix soil, create pores, and incorporate organic matter.

- Microbes: Bacteria and fungi are the primary drivers of decomposition, nutrient cycling, and the formation of stable soil aggregates.

The type and abundance of organisms directly influence the amount and quality of organic matter in the soil.

- Time: Soil formation is a slow process, requiring hundreds to thousands of years for significant development. Over time, the other four factors interact to create distinct soil layers, known as horizons. Young soils closely resemble their parent material, while older soils show more developed horizons and distinct characteristics.

Types of Soil: A World of Diversity

Just as there are countless landscapes, there are innumerable types of soil, each with unique properties. While a detailed classification involves complex systems, understanding basic soil types helps us appreciate their diversity. Soils are often described by their texture, which is the proportion of sand, silt, and clay.

- Sandy Soils: Feel gritty, drain quickly, and warm up fast. They are often low in nutrients.

- Silty Soils: Feel smooth and floury, retain moisture well, and are generally fertile.

- Clay Soils: Feel sticky when wet, hold water and nutrients exceptionally well, but can become compacted and poorly drained.

- Loam Soils: Considered ideal for agriculture, loam is a balanced mixture of sand, silt, and clay, offering good drainage, aeration, and nutrient retention.

Beyond texture, soils develop distinct layers called horizons. A typical soil profile might include:

- O Horizon: The uppermost layer, rich in organic matter, consisting of decomposing leaves and plant litter.

- A Horizon (Topsoil): Dark, rich in humus and mineral particles, this is where most biological activity occurs and where plants primarily root.

- B Horizon (Subsoil): Lighter in color, this layer accumulates clay, iron, and aluminum leached from above.

- C Horizon (Parent Material): Partially weathered rock or unconsolidated sediment, showing little biological activity.

- R Horizon (Bedrock): The unweathered parent rock.

The Indispensable Role of Soil: Why It Matters

The importance of soil extends far beyond its scientific intrigue. It is a fundamental component of Earth’s life support systems, providing a multitude of ecosystem services that are vital for human well-being and planetary health.

- Food Production: Over 95% of our food directly or indirectly comes from soil. Healthy soil provides the nutrients, water, and physical support necessary for crops to grow, making it the bedrock of global food security.

- Water Filtration and Storage: Soil acts as a natural filter, purifying rainwater as it percolates through its layers, removing pollutants and contaminants before it reaches groundwater. It also stores vast quantities of water, regulating water flow and preventing floods.

- Carbon Sequestration: Soil is one of the largest terrestrial carbon sinks. Organic matter in soil stores significant amounts of carbon, playing a critical role in mitigating climate change by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Habitat for Biodiversity: Soil is home to a quarter of all known species on Earth, a staggering diversity of organisms that contribute to nutrient cycling, pest control, and disease suppression.

- Foundation for Infrastructure: Our homes, roads, and buildings are all built upon soil. Its stability and engineering properties are crucial for supporting human infrastructure.

- Nutrient Cycling: Soil organisms tirelessly break down organic matter, releasing essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in forms that plants can use, ensuring the continuous fertility of ecosystems.

Protecting Our Precious Soil

Despite its immense importance, soil is a fragile resource, vulnerable to degradation from human activities. Soil erosion, compaction, pollution, and loss of organic matter threaten its ability to perform its vital functions.

- Erosion: The loss of topsoil due to wind and water is a major global problem, reducing soil fertility and polluting waterways.

- Compaction: Heavy machinery and livestock can compact soil, reducing pore space, hindering root growth, and decreasing water infiltration.

- Pollution: Industrial chemicals, pesticides, and improper waste disposal can contaminate soil, making it toxic for plants and organisms.

- Loss of Organic Matter: Intensive farming practices that do not replenish organic matter can deplete soil fertility and structure.

Fortunately, sustainable soil management practices can help protect and restore this invaluable resource:

- Cover Cropping: Planting non-cash crops between main harvests protects the soil from erosion, adds organic matter, and suppresses weeds.

- No-Till or Minimum Tillage: Reducing soil disturbance helps maintain soil structure, organic matter, and the soil food web.

- Crop Rotation: Varying crops grown in a field over time helps manage pests, diseases, and nutrient demands.

- Adding Organic Matter: Composting, mulching, and incorporating animal manures enrich the soil with vital organic material.

- Sustainable Grazing: Managing livestock to prevent overgrazing helps maintain healthy grasslands and soil structure.

A Call to Appreciate the Earth Beneath Us

Soil is a miracle beneath our feet, a complex, living system that underpins nearly every aspect of life on Earth. From the food we eat and the water we drink to the air we breathe and the biodiversity that surrounds us, soil is an unsung hero. By understanding its composition, its intricate food web, its slow formation, and its indispensable roles, we can cultivate a deeper appreciation for this vital resource. Protecting and nurturing our soil is not just an ecological imperative, it is an investment in the future health and prosperity of all life on our planet. Let us recognize soil for the living wonder it truly is.