The Incredible Journey: Unraveling the Wonders of Seed Dispersal

Life on Earth is a constant dance of survival and propagation. For plants, rooted to a single spot, this presents a unique challenge: how do they spread their offspring to new, fertile grounds? The answer lies in one of nature’s most ingenious strategies: seed dispersal. Far from being a passive process, seed dispersal is a dynamic, often spectacular, phenomenon that underpins the very fabric of ecosystems, influencing everything from forest regeneration to the distribution of plant species across continents.

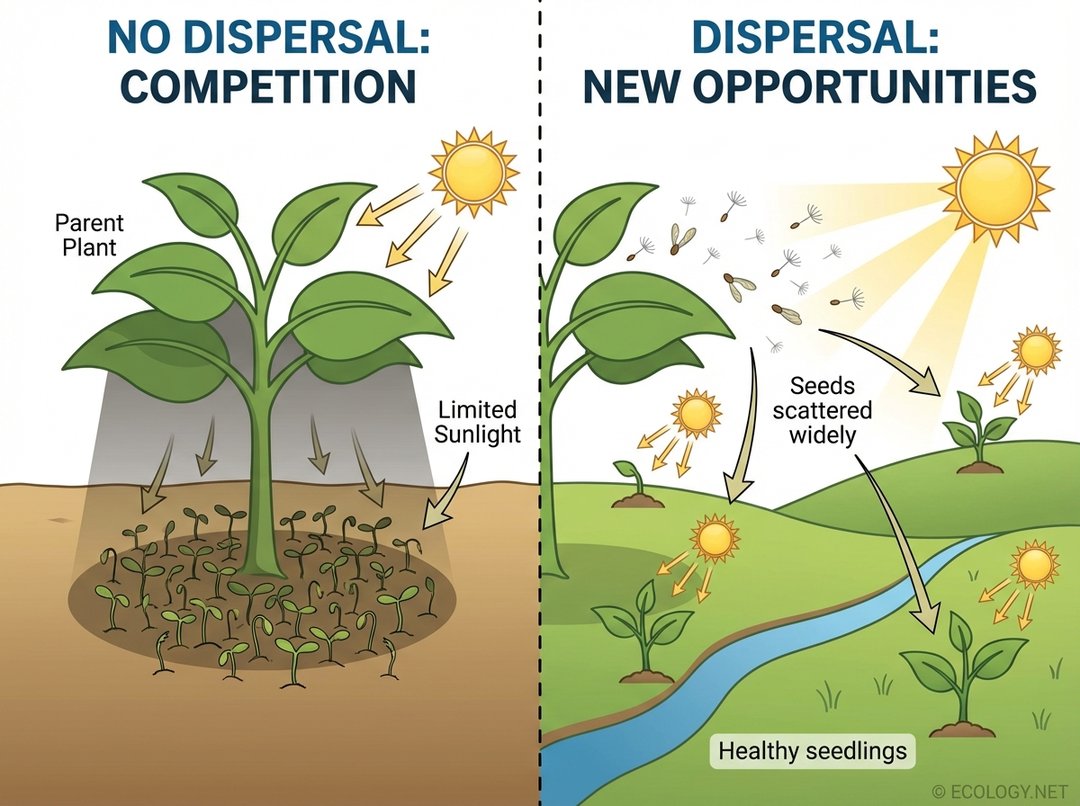

Understanding seed dispersal is not just about appreciating the cleverness of nature; it is about grasping a fundamental ecological process that ensures plant survival, reduces competition, and allows for the colonization of new habitats. Without it, plant life would be confined to dense, struggling clusters, unable to adapt or thrive.

Why Seeds Must Travel: The Ecological Imperative

Imagine a mighty oak tree. If all its acorns simply dropped directly beneath its canopy, what would happen? A dense carpet of oak seedlings would emerge, all vying for the same limited sunlight, water, and nutrients. Most would perish, choked out by their siblings and overshadowed by their towering parent. This intense competition is precisely what seed dispersal aims to avoid.

The primary reasons for seeds to embark on their journeys are compelling:

- Reducing Competition: By moving away from the parent plant, seeds avoid direct competition for resources with their own kind and the established adult. This gives individual seedlings a much better chance of survival.

- Colonizing New Habitats: Dispersal allows plants to reach and establish themselves in new areas, expanding their range and increasing their overall population size. This is crucial for adapting to environmental changes.

- Escaping Pathogens and Predators: A dense cluster of seeds or seedlings is an easy target for diseases and herbivores. Spreading out reduces the likelihood of an entire generation being wiped out by a localized threat.

- Promoting Genetic Diversity: When seeds travel, they can potentially interbreed with plants from different populations, leading to greater genetic variation within the species. This genetic diversity is vital for long-term resilience and evolution.

The Four Main Modes of Seed Dispersal: Nature’s Diverse Strategies

Plants have evolved an astonishing array of mechanisms to ensure their seeds reach new destinations. These methods can broadly be categorized into four main modes, each with its own unique adaptations and ecological implications.

1. Wind Dispersal (Anemochory)

For many plants, the wind serves as a powerful, widespread, and free mode of transport. Seeds adapted for wind dispersal often possess specialized structures that allow them to catch the breeze and float away. Think of the iconic dandelion, with its parachute-like pappus, or the maple tree’s samaras, often called “helicopters,” which spin as they fall, slowing their descent and allowing the wind to carry them further. Orchids produce dust-like seeds, so tiny and light that they can be carried thousands of kilometers by air currents. This method is particularly effective for plants in open environments where wind is abundant.

2. Water Dispersal (Hydrochory)

Plants growing near water bodies, such as rivers, lakes, or oceans, often utilize water currents to distribute their seeds. These seeds are typically buoyant and waterproof, designed to float for extended periods. The most famous example is the coconut, whose fibrous husk allows it to drift across vast stretches of ocean, colonizing new islands. Water lilies release seeds that float for a time before sinking, while some sedges and rushes have seeds that are carried by flowing water along riverbanks.

3. Animal Dispersal (Zoochory)

Animals are unwitting, and sometimes willing, partners in seed dispersal, playing a crucial role in spreading seeds across landscapes. This method is incredibly diverse, ranging from seeds hitching a ride on fur to being consumed and later excreted. Birds, mammals, insects, and even reptiles contribute to this widespread form of dispersal. Examples include squirrels burying acorns, birds eating berries and dispersing seeds in their droppings, and burdock seeds clinging to animal fur.

4. Explosive Dispersal (Autochory or Ballochory)

Some plants take matters into their own “hands,” employing a fascinating self-dispersal mechanism. These plants have fruits or pods that build up tension as they mature. When ripe, they burst open with considerable force, ejecting seeds away from the parent plant. The touch-me-not plant, also known as jewelweed, is a prime example; its ripe seed pods explode at the slightest touch, scattering seeds several feet away. Violets and some legumes also use this method, ensuring their seeds get a forceful start on their journey.

A Closer Look at Animal Dispersal: External vs. Internal Journeys

Animal dispersal, or zoochory, is a particularly intricate and widespread strategy, often involving co-evolutionary relationships between plants and animals. It can be further divided into two main categories based on how the seeds interact with the animal.

Epizoochory: The Hitchhikers

Epizoochory refers to seeds that attach to the exterior of an animal. These seeds often possess specialized structures like hooks, barbs, sticky coatings, or burrs that allow them to cling to fur, feathers, or even clothing. The common burdock, with its tenacious burrs, is a classic example. These seeds simply wait for an unsuspecting animal to brush past, latch on, and are then carried away, sometimes for considerable distances, before eventually falling off or being groomed away. This method is a brilliant passive strategy, turning animal movement into a dispersal vector.

Endozoochory: The Internal Travelers

Endozoochory involves seeds that are consumed by an animal and then dispersed after passing through its digestive tract. Plants employing this strategy often produce fleshy, nutritious fruits that entice animals to eat them. The fruit provides a reward for the animal, while the seeds, often protected by a hard coat, survive digestion. When the animal defecates, the seeds are deposited, often with a ready supply of fertilizer, in a new location. Birds eating berries, mammals consuming larger fruits like apples or plums, and even fish eating aquatic plant seeds are all examples of endozoochory. This method is highly effective for long-distance dispersal and can even aid in seed germination by scarifying the seed coat.

The Broader Ecological Impact of Seed Dispersal

The mechanisms of seed dispersal are not just fascinating biological curiosities; they are fundamental drivers of ecological processes. They dictate the distribution patterns of plant species, influence the structure and composition of plant communities, and play a critical role in ecosystem resilience. For instance, after a disturbance like a forest fire, seed dispersal is essential for the recolonization of the damaged area. It also facilitates gene flow between isolated plant populations, which is vital for maintaining genetic health and adaptability in the face of environmental change.

From the smallest wildflower to the tallest tree, every plant has an evolutionary story of how its seeds travel. These journeys, whether by wind, water, animal, or explosive force, are a testament to nature’s endless creativity and the profound interconnectedness of life on Earth. By understanding seed dispersal, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate strategies that allow plant life to thrive and shape the world around us.