The natural world is a tapestry woven with countless interactions, and among the most fundamental and dramatic are those between predators and their prey. Often, our minds conjure images of majestic lions chasing gazelles across the savanna, or a powerful eagle snatching a fish from a pristine lake. While these classic examples certainly embody the essence of predation, the reality is far more intricate, diverse, and utterly fascinating.

Predators are not merely the “bad guys” of the animal kingdom; they are essential architects of ecosystems, driving evolution, shaping landscapes, and maintaining ecological balance. To truly appreciate their profound impact, we must first expand our understanding of what a predator truly is.

What Exactly is a Predator? Redefining the Hunt

At its core, a predator is an organism that obtains energy by killing and consuming another organism, known as its prey. This definition, however, is much broader than many realize. It extends far beyond the familiar image of a carnivore hunting another animal. The ecological role of a predator encompasses a surprising variety of life forms and strategies, each playing a vital part in the intricate web of life.

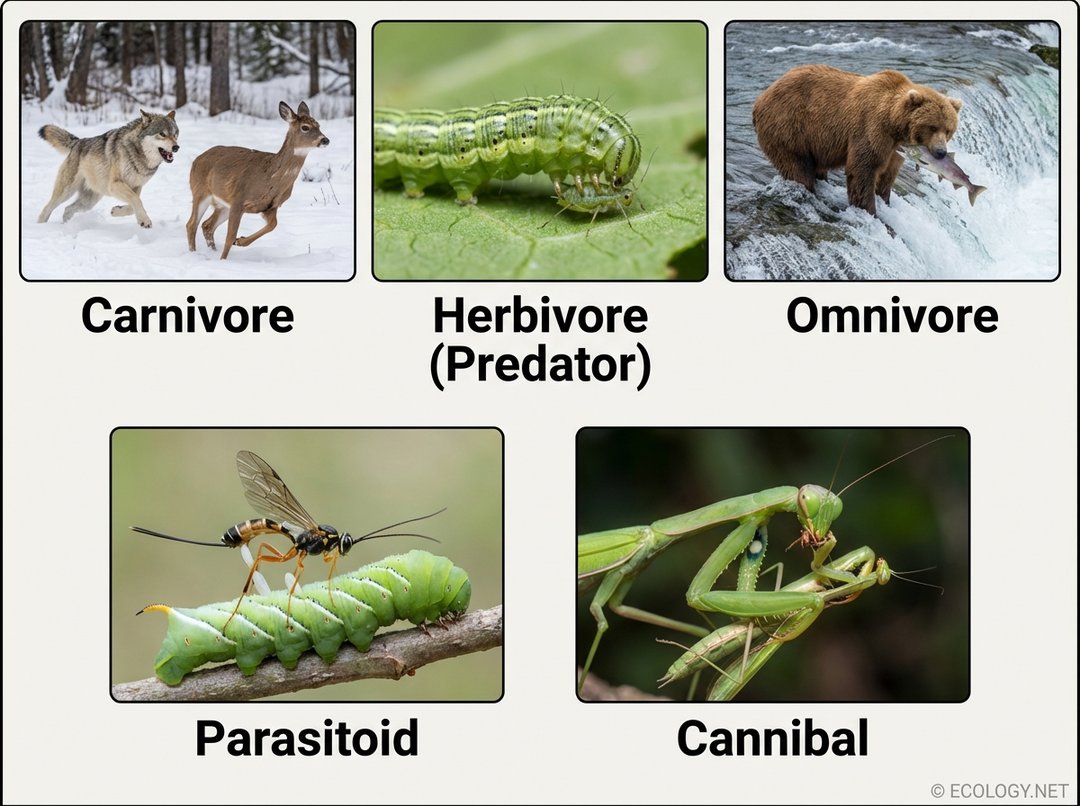

This image visually clarifies the diverse definitions and categories of predators discussed in the article, moving beyond the common perception of just meat-eating carnivores to include other fascinating strategies.

Beyond the Bite: A Spectrum of Predatory Strategies

The ecological classification of predators reveals a rich spectrum of interactions:

- Carnivores: These are the classic predators we often imagine. Carnivores primarily consume other animals. Examples abound, from the swift wolf pursuing its quarry to the stealthy leopard ambushing its prey, or the powerful shark dominating marine environments. Their bodies are often specialized for hunting, with sharp teeth, claws, and keen senses.

- Herbivores (Predators): While the term “herbivore” typically refers to plant-eaters, the concept of predation can extend to organisms that consume other living organisms, even if those are plants. For instance, a caterpillar consuming a smaller insect, as depicted in the diagram, highlights that even organisms often associated with a plant-based diet can engage in predatory behavior. This demonstrates the nuanced and sometimes overlapping roles within ecosystems, where the act of consuming another living organism for sustenance is the defining characteristic of predation. Seed predators, which consume entire plant embryos, are another example of herbivores acting as predators.

- Omnivores: These versatile predators have a diet that includes both plants and animals. Bears, for example, will readily catch fish, hunt small mammals, and consume berries, nuts, and roots. Humans are also prime examples of omnivores, adapting their diets to a wide range of available food sources. Raccoons, foxes, and many bird species also fall into this category, showcasing adaptability in their feeding strategies.

- Parasitoids: These are a particularly gruesome and fascinating group. Unlike parasites, which typically do not kill their hosts, parasitoids eventually kill their host as part of their life cycle. A common example is the parasitic wasp, which lays its eggs inside or on a host caterpillar. The wasp larvae then hatch and slowly consume the caterpillar from the inside out, ultimately leading to its death. This strategy is a highly specialized form of predation, crucial for controlling insect populations.

- Cannibals: In some species, individuals consume members of their own kind. This behavior, known as cannibalism, can occur for various reasons, including resource scarcity, population control, or even sexual selection. The praying mantis is a well-known example, where the female often consumes the male during or after mating. Certain fish species, spiders, and even some amphibians also exhibit cannibalistic tendencies, particularly towards their young or weaker individuals.

The Evolutionary Arms Race: Predator vs. Prey

The relationship between predators and prey is not static; it is a dynamic, ongoing evolutionary “arms race.” Over countless generations, predators have evolved more effective hunting strategies, while prey have simultaneously developed more sophisticated defenses. This constant interplay drives natural selection, leading to an astonishing array of adaptations on both sides.

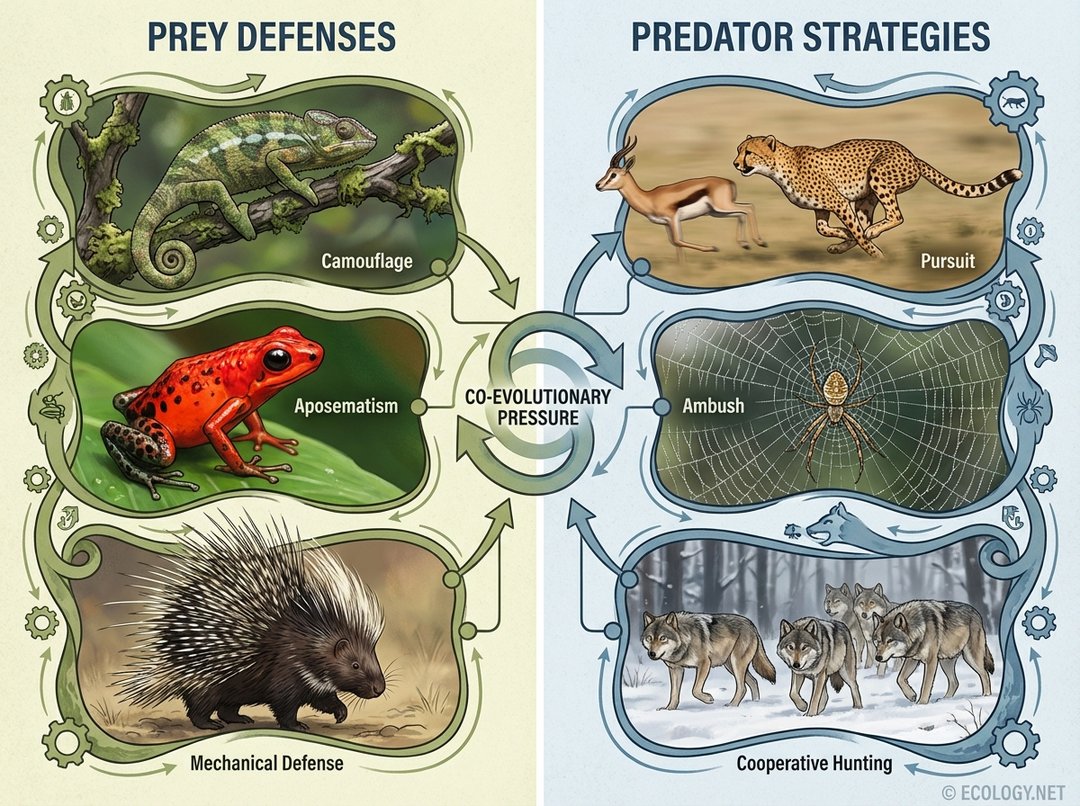

This image illustrates the constant evolutionary interplay between predators and prey, showcasing various defensive mechanisms developed by prey and the corresponding diverse hunting strategies employed by predators, as detailed in the article.

Prey Defenses: Masters of Survival

Prey species have developed an incredible repertoire of defenses to avoid becoming a meal:

- Camouflage: Blending seamlessly into the environment is a primary defense. A chameleon changing its skin color to match a branch, a stick insect mimicking a twig, or an arctic fox’s coat turning white in winter are all examples of camouflage designed to evade detection.

- Warning Coloration (Aposematism): Some prey species advertise their toxicity or unpalatability with bright, conspicuous colors. The vibrant hues of a poison dart frog or the striking patterns of a monarch butterfly warn potential predators that they are not a desirable meal.

- Mimicry: This involves one species evolving to resemble another.

- Batesian Mimicry: A harmless species mimics a harmful one, like a hoverfly resembling a stinging wasp.

- Müllerian Mimicry: Two or more harmful species evolve to resemble each other, reinforcing the warning signal to predators, such as various species of unpalatable butterflies sharing similar patterns.

- Physical Defenses: Many animals possess physical deterrents. Porcupines raise their sharp quills, armadillos curl into armored balls, and turtles retreat into their shells. Horns, antlers, and tough hides also serve as formidable protection.

- Chemical Defenses: Skunks release foul-smelling sprays, bombardier beetles eject boiling hot chemicals, and many plants produce toxic compounds to deter herbivores.

- Behavioral Defenses: These include fleeing, freezing, forming groups (like fish schooling or wildebeest herds), alarm calls, and even playing dead (thanatosis).

Predator Strategies: The Art of the Hunt

Not to be outdone, predators have evolved equally impressive methods for capturing their prey:

- Pursuit: High-speed chases are characteristic of predators like cheetahs, which can reach incredible speeds, or wolves, which use endurance to wear down their prey.

- Ambush: Many predators rely on surprise. Crocodiles wait patiently beneath the water’s surface, praying mantises blend into foliage, and some snakes lie motionless, striking only when prey is within reach.

- Trapping: Spiders spin intricate webs, antlions dig conical pits, and anglerfish use bioluminescent lures to attract unsuspecting prey.

- Cooperative Hunting: Some of the most intelligent predators hunt in groups. Wolves coordinate their attacks to take down large prey, orcas work together to create waves that wash seals off ice floes, and lions cooperate to encircle herds.

- Mimicry: Predators can also use mimicry to their advantage. The orchid mantis resembles a flower to ambush pollinating insects, and some snakes mimic venomous species to deter other predators.

- Tool Use: While less common, some predators employ tools. Sea otters use rocks to crack open shellfish, and certain birds use twigs to extract insects from crevices.

Predators as Architects of Ecosystems: The Trophic Cascade

Beyond their direct impact on prey populations, predators play a profound role in shaping entire ecosystems. Their presence, or absence, can trigger a series of dramatic changes known as a trophic cascade. This concept highlights how changes at one trophic (feeding) level can have cascading effects throughout the food web, often with far-reaching consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem health.

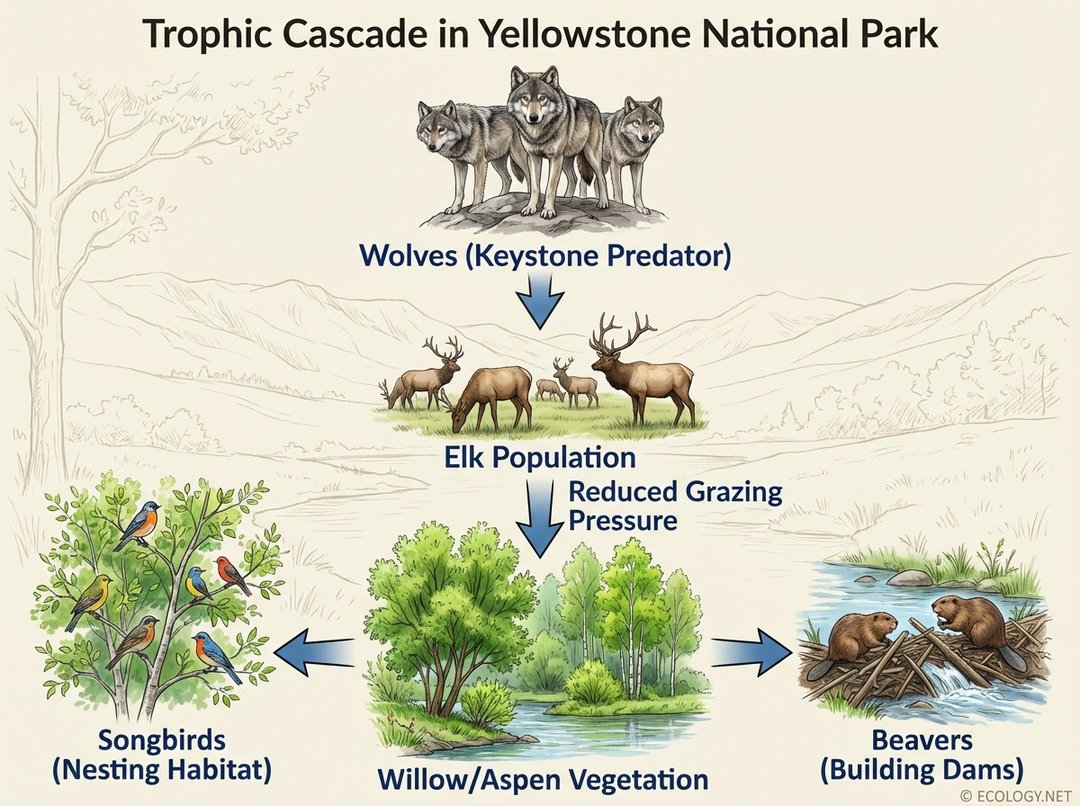

This image visually explains the crucial concept of a trophic cascade, using the impactful real-world example of wolves in Yellowstone National Park, demonstrating how a keystone predator can dramatically influence an entire ecosystem.

The Yellowstone Story: A Case Study in Ecological Restoration

One of the most compelling real-world examples of a trophic cascade comes from Yellowstone National Park in the United States. For decades, wolves, the park’s apex predator, were hunted to extinction in the region by the 1920s. Their absence led to a dramatic imbalance:

- Elk Overpopulation: Without wolves to control their numbers, the elk population exploded.

- Vegetation Degradation: The unchecked elk herds overgrazed riparian areas, consuming young willow and aspen trees. This led to a decline in these crucial plant species, which are vital for stabilizing riverbanks and providing habitat.

- Loss of Biodiversity: The decline in willow and aspen had ripple effects. Beaver populations, which rely on these trees for food and dam building, plummeted. Songbird populations, dependent on the trees for nesting sites, also suffered. The degraded riverbanks led to increased erosion and warmer stream temperatures, negatively impacting fish and amphibian populations.

In 1995, wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone. The results were nothing short of miraculous:

- Elk Behavior Changed: While wolf predation did reduce elk numbers, a more significant impact was the change in elk behavior. Elk became more vigilant and avoided areas where they were vulnerable, such as river valleys, allowing vegetation to recover.

- Vegetation Recovery: With reduced grazing pressure, willow and aspen trees began to grow taller and denser.

- Ecosystem Restoration: The recovering vegetation had profound cascading effects.

- Beaver populations rebounded, building dams that created new wetland habitats.

- Songbird numbers increased as nesting sites became more abundant.

- The stabilized riverbanks reduced erosion, leading to clearer, colder streams, benefiting fish.

- Even scavenger populations, like ravens and eagles, benefited from wolf kills.

The Yellowstone story vividly demonstrates that top predators are not just hunters; they are keystone species, whose presence is critical for maintaining the health, structure, and biodiversity of an entire ecosystem. Their influence extends far beyond their immediate prey, shaping landscapes and supporting a multitude of other species.

Human Impact and Conservation of Predators

Historically, humans have often viewed predators with a mix of fear, awe, and competition. Predators have been persecuted for preying on livestock, feared for potential threats to humans, and hunted for sport or fur. This often led to drastic declines in predator populations, with devastating consequences for ecosystems, as seen in Yellowstone.

Today, there is a growing understanding of the indispensable role predators play. Conservation efforts increasingly focus on protecting predator species and their habitats. This involves:

- Habitat Preservation: Ensuring large, connected areas where predators can roam and find prey.

- Reducing Human-Wildlife Conflict: Implementing strategies like non-lethal deterrents for livestock protection, education, and compensation programs.

- Reintroduction Programs: Bringing back apex predators to areas where they were extirpated, as successfully done with wolves in Yellowstone.

- Public Education: Changing public perception from fear to appreciation for the ecological services predators provide.

Conclusion

Predators, in all their diverse forms, are far more than just hunters. They are vital components of ecological systems, driving evolution, maintaining population health, and shaping the very structure of habitats. From the microscopic world to the vast wilderness, the intricate dance between predator and prey is a fundamental force of nature, a testament to the complexity and resilience of life on Earth.

Understanding and appreciating the multifaceted roles of predators is crucial for effective conservation and for fostering a deeper connection with the natural world. By recognizing their importance, we can work towards a future where these magnificent and essential creatures continue to thrive, ensuring the health and balance of our planet’s precious ecosystems for generations to come.