Humanity’s relationship with the natural world is a delicate balance, one often tested by our growing needs and technological prowess. Among the most pressing environmental challenges we face today is overharvesting, a phenomenon that threatens biodiversity, destabilizes ecosystems, and undermines the very resources upon which we depend. Understanding overharvesting is crucial for safeguarding the planet’s future and ensuring the sustainability of its precious biological wealth.

What is Overharvesting?

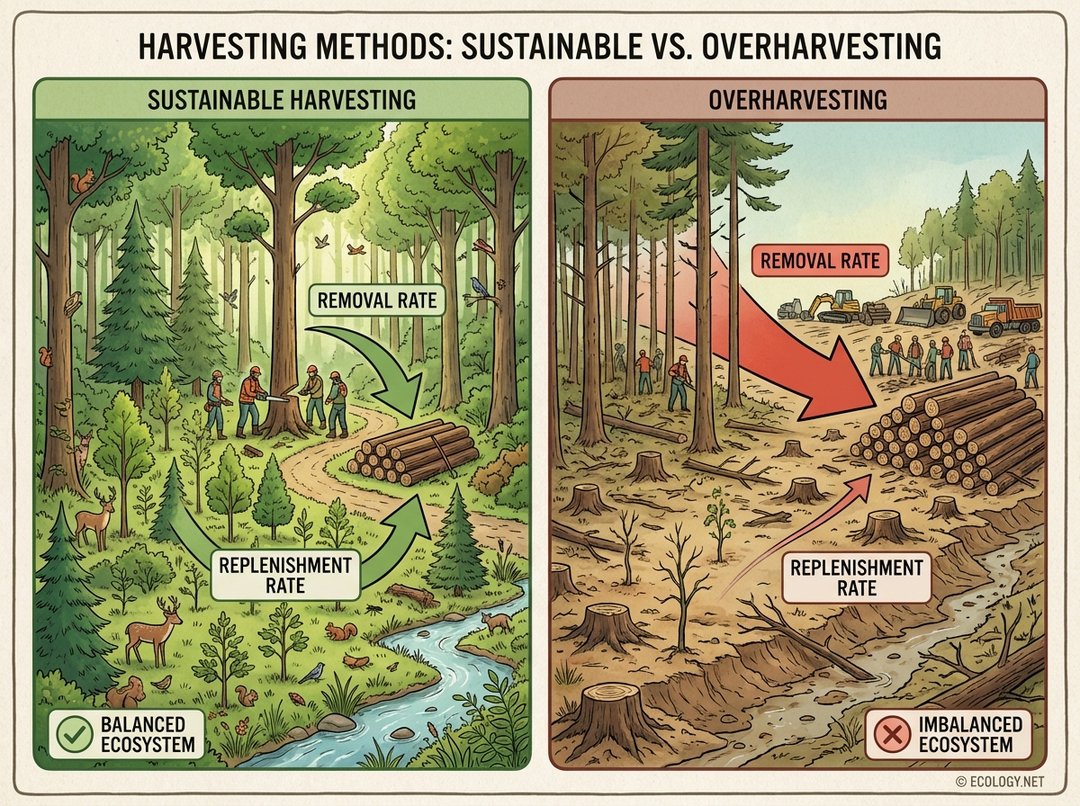

At its core, overharvesting refers to the act of harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. This occurs when the rate at which a resource is removed from its natural environment exceeds its capacity to replenish itself. Imagine a forest where trees are cut down faster than new ones can grow, or a fish population caught at a rate that prevents it from reproducing sufficiently to maintain its numbers. This imbalance between removal and replenishment is the hallmark of overharvesting.

Sustainable harvesting, in contrast, involves utilizing a resource in a manner that allows it to regenerate naturally, ensuring its availability for future generations. It respects the ecological limits of the system, maintaining a healthy equilibrium. Overharvesting, however, pushes these limits, leading to a decline in the resource and often, broader ecological damage.

A Glimpse into History: The Passenger Pigeon’s Tragic Tale

The consequences of overharvesting are not merely theoretical; history offers stark reminders of its destructive power. Perhaps one of the most poignant examples is the story of the Passenger Pigeon.

Once the most abundant bird in North America, possibly even the world, Passenger Pigeons darkened the skies in flocks so vast they could take hours to pass overhead. Their numbers were estimated in the billions. Early European settlers marveled at their seemingly endless supply, viewing them as a cheap and readily available food source.

However, a combination of factors led to their rapid demise. Unregulated hunting, driven by commercial markets and facilitated by new technologies like railroads and telegraphs, allowed hunters to track and decimate breeding colonies with unprecedented efficiency. Millions of birds were harvested annually, often for their meat, feathers, and even for sport. Habitat destruction also played a role, but the sheer scale of direct harvesting was the primary driver.

Within a few decades, the seemingly inexhaustible flocks dwindled to mere hundreds, then dozens. The last known Passenger Pigeon, named Martha, died in captivity in 1914, marking the complete extinction of a species that once symbolized abundance. This tragic event serves as a powerful cautionary tale, demonstrating how even seemingly limitless resources can be driven to oblivion through unchecked exploitation.

Modern Manifestations and Ecological Consequences

While the Passenger Pigeon is a historical example, overharvesting continues to be a pervasive issue today, affecting a wide array of resources and ecosystems. Its impacts are far-reaching, leading to a cascade of ecological and socio-economic problems.

Fisheries in Crisis

One of the most prominent areas where overharvesting is evident is in global fisheries. Decades of intensive commercial fishing, often employing highly efficient but non-selective gear, have pushed many fish stocks to the brink of collapse. Species like Atlantic cod, bluefin tuna, and various shark populations have seen dramatic declines, impacting marine food webs and the livelihoods of fishing communities.

A significant problem in commercial fishing is bycatch. This refers to the accidental capture of non-target species during fishing operations. Trawling nets, longlines, and gillnets, while effective at catching desired fish, often ensnare marine mammals, sea turtles, seabirds, and juvenile fish of other species. These animals are typically discarded, often dead or dying, representing a massive waste of marine life and a significant ecological toll.

Beyond the Oceans: Terrestrial and Botanical Overharvesting

Overharvesting is not confined to marine environments. It manifests in various forms across terrestrial ecosystems:

- Deforestation: Illegal logging and unsustainable timber harvesting contribute to the rapid loss of forests, particularly in tropical regions. This destroys critical habitats, exacerbates climate change, and leads to soil erosion.

- Bushmeat Trade: The unsustainable hunting of wild animals for food, often referred to as the bushmeat trade, threatens numerous species, especially in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America. This practice can decimate local wildlife populations and even facilitate the spread of zoonotic diseases.

- Medicinal Plants and Herbs: Many plant species with medicinal properties are collected from the wild at unsustainable rates, leading to their endangerment. This not only threatens biodiversity but also impacts traditional medicine practices.

- Exotic Pet Trade: The demand for exotic pets drives the illegal capture of wild animals, from reptiles and birds to primates, often with high mortality rates during capture and transport.

Broader Ecological Impacts

The consequences of overharvesting extend far beyond the immediate depletion of a single resource:

- Loss of Biodiversity: The most direct impact is the reduction in species populations, leading to endangerment and extinction. This diminishes the overall variety of life on Earth.

- Ecosystem Imbalance: Removing a key species can have ripple effects throughout an ecosystem. For example, overfishing of a predator can lead to an explosion in its prey population, which in turn might overgraze marine plants, altering the entire habitat.

- Habitat Degradation: Destructive harvesting methods, such as bottom trawling in fisheries or clear-cutting in forests, can physically damage habitats, making recovery difficult.

- Genetic Erosion: When only the largest or most desirable individuals are consistently harvested, it can lead to a reduction in genetic diversity within a population, making it less resilient to environmental changes or diseases.

- Economic and Social Disruption: Communities reliant on natural resources for their livelihoods suffer when those resources are depleted, leading to poverty, displacement, and conflict.

Drivers of Overharvesting

Understanding why overharvesting occurs requires examining a complex interplay of factors:

- Population Growth and Increased Demand: A growing global population naturally places greater demands on natural resources for food, fuel, and materials.

- Technological Advancements: Modern harvesting technologies, from powerful fishing vessels with advanced sonar to heavy machinery for logging, allow for extraction on an unprecedented scale and efficiency.

- Economic Pressures and Poverty: In many developing regions, immediate economic needs can drive unsustainable harvesting practices, as individuals and communities may have few other options for survival.

- Lack of Regulation and Enforcement: Weak governance, corruption, and insufficient monitoring allow illegal and unregulated harvesting to flourish. International waters, in particular, often suffer from a “tragedy of the commons” where resources are exploited without adequate oversight.

- Market Forces and Consumer Behavior: High consumer demand for certain products, whether exotic foods, luxury goods, or cheap timber, can create powerful incentives for overharvesting.

- Ignorance and Lack of Awareness: Sometimes, overharvesting occurs simply because the long-term ecological consequences are not fully understood or communicated to those involved in resource extraction or consumption.

Pathways to Sustainability: Addressing Overharvesting

Reversing the trend of overharvesting requires a multi-faceted approach involving policy, technology, and individual action.

Effective Resource Management and Policy

- Quotas and Catch Limits: Implementing scientifically determined quotas for fisheries and other resources can ensure that removal rates do not exceed replenishment rates.

- Protected Areas: Establishing marine protected areas (MPAs) and terrestrial reserves provides safe havens for species to recover and reproduce, acting as nurseries for surrounding areas.

- Sustainable Forestry and Fisheries Certifications: Programs like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) for timber and the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) for seafood help consumers identify products sourced from sustainably managed operations.

- International Cooperation: Many resources, particularly migratory fish stocks and endangered species, cross national borders, necessitating international agreements and collaborative management efforts.

Technological Innovation and Responsible Practices

- Selective Fishing Gear: Developing and deploying fishing gear that minimizes bycatch, such as turtle excluder devices (TEDs) or modified longlines, can significantly reduce unintended harm.

- Improved Monitoring: Satellite tracking, drone technology, and advanced data analytics can help monitor resource populations and detect illegal harvesting activities more effectively.

- Aquaculture and Mariculture: Responsibly managed aquaculture (farming of aquatic organisms) can reduce pressure on wild fish stocks, though it must be carefully implemented to avoid its own environmental impacts.

Consumer Awareness and Demand

- Informed Choices: Consumers have significant power. By choosing sustainably sourced products, supporting certified businesses, and reducing consumption of overharvested species, individuals can drive market demand towards more responsible practices.

- Reducing Waste: Minimizing food waste, particularly seafood, can lessen the overall demand on natural resources.

- Advocacy and Education: Supporting conservation organizations and advocating for stronger environmental policies can create systemic change.

Conclusion

Overharvesting stands as a stark reminder of humanity’s capacity to deplete the very natural capital that sustains us. From the silent skies once filled with Passenger Pigeons to the struggling fish populations of today’s oceans, the evidence is clear: unchecked exploitation leads to irreversible loss. However, the story does not end with despair. Through informed policy, responsible innovation, and conscious consumer choices, we possess the collective ability to shift towards a future where our needs are met without compromising the health and abundance of the natural world. The challenge is immense, but the imperative to protect our planet’s biodiversity and ensure sustainable resources for generations to come is even greater.