The Silent Crisis Beneath the Waves: Understanding Overfishing

The ocean, a vast and mysterious realm, has long been perceived as an inexhaustible larder, teeming with life ready to sustain humanity. For millennia, fishing has been a cornerstone of human civilization, providing food, livelihoods, and cultural heritage. Yet, beneath the surface of this seemingly endless bounty, a silent crisis has been unfolding: overfishing. This pervasive issue threatens not only the delicate balance of marine ecosystems but also the very communities and economies that depend on the ocean’s health. Understanding overfishing is the first crucial step toward safeguarding our planet’s most vital resource.

What is Overfishing? A Depletion of Our Ocean’s Capital

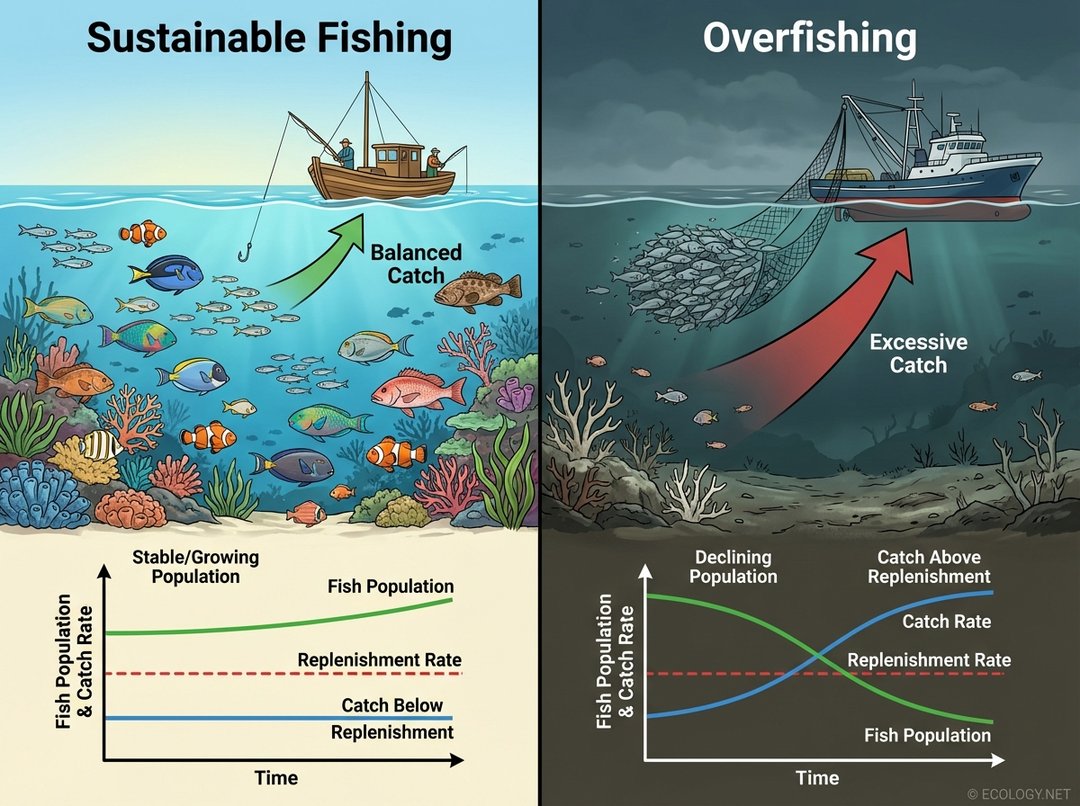

At its core, overfishing occurs when fish are caught faster than their populations can replenish themselves through natural reproduction. Imagine a bank account: sustainable fishing is like living off the interest, taking only what the account generates annually, ensuring the principal remains intact and continues to grow. Overfishing, however, is akin to dipping into the principal, year after year, until the account is depleted.

This imbalance leads to a decline in fish stocks, reducing the number of fish available for future generations and disrupting the intricate web of marine life. It is a critical distinction from simply “fishing,” which is a necessary and often sustainable human activity.

Distinguishing Overfishing from Sustainable Fishing

The key difference lies in the rate of extraction versus the rate of renewal.

- Sustainable Fishing: This practice ensures that fish populations remain healthy and productive over time. It involves catching fish at a rate that allows the species to reproduce and maintain its population size, often leaving enough fish in the water to support the ecosystem. Methods are typically selective, minimizing bycatch and habitat damage.

- Overfishing: This occurs when fishing pressure is too high, leading to a significant reduction in the abundance of a fish stock. The catch rate exceeds the population’s ability to recover, resulting in smaller fish, fewer fish, and eventually, a collapse of the fishery. A classic example is the collapse of the Grand Banks cod fishery in the late 20th century, where once-abundant stocks dwindled to critical levels due to decades of intense fishing pressure.

The Ripple Effects: Ecological Consequences of Overfishing

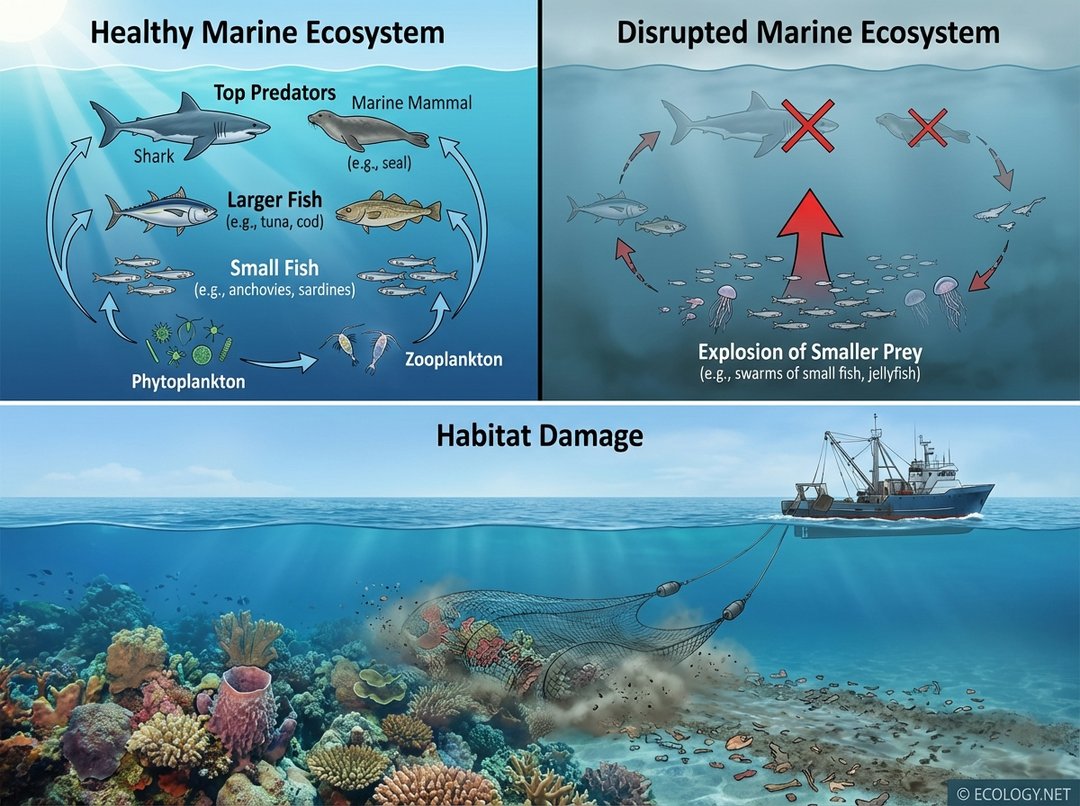

The ocean is a complex, interconnected system. Removing too many fish from one part of this system inevitably sends shockwaves throughout, leading to a cascade of ecological problems.

Disrupted Food Webs

Fish are integral components of marine food webs, acting as both predators and prey.

- Top Predator Decline: When large predatory fish like tuna, sharks, and cod are overfished, their populations plummet. This can lead to an increase in their prey species, such as smaller fish or jellyfish, which can then overgraze on their own food sources, like zooplankton or larval fish.

- Trophic Cascades: This imbalance can trigger a “trophic cascade,” where changes at one level of the food web have dramatic effects on other levels. For instance, the removal of sharks can lead to an explosion of rays, which then consume vast quantities of scallops, impacting commercial fisheries for those shellfish.

Habitat Damage

Certain fishing methods are incredibly destructive to the marine environment.

- Bottom Trawling: This technique involves dragging heavy nets along the ocean floor, indiscriminately scooping up everything in their path. This process can pulverize delicate habitats like coral reefs, sponge gardens, and seagrass beds, which are vital nurseries and feeding grounds for countless marine species. The damage can take decades, if not centuries, to recover.

- Ghost Fishing: Lost or abandoned fishing gear, known as “ghost gear,” continues to trap and kill marine life for years. Nets, lines, and traps become deadly hazards for fish, turtles, seabirds, and marine mammals.

Biodiversity Loss

Overfishing directly contributes to the decline and potential extinction of marine species. When a specific fish stock is overfished, its genetic diversity can also be reduced, making the population more vulnerable to diseases and environmental changes. Furthermore, the bycatch associated with many fishing methods, where non-target species are caught and discarded, adds to the pressure on marine biodiversity.

The Culprits: Why Does Overfishing Happen?

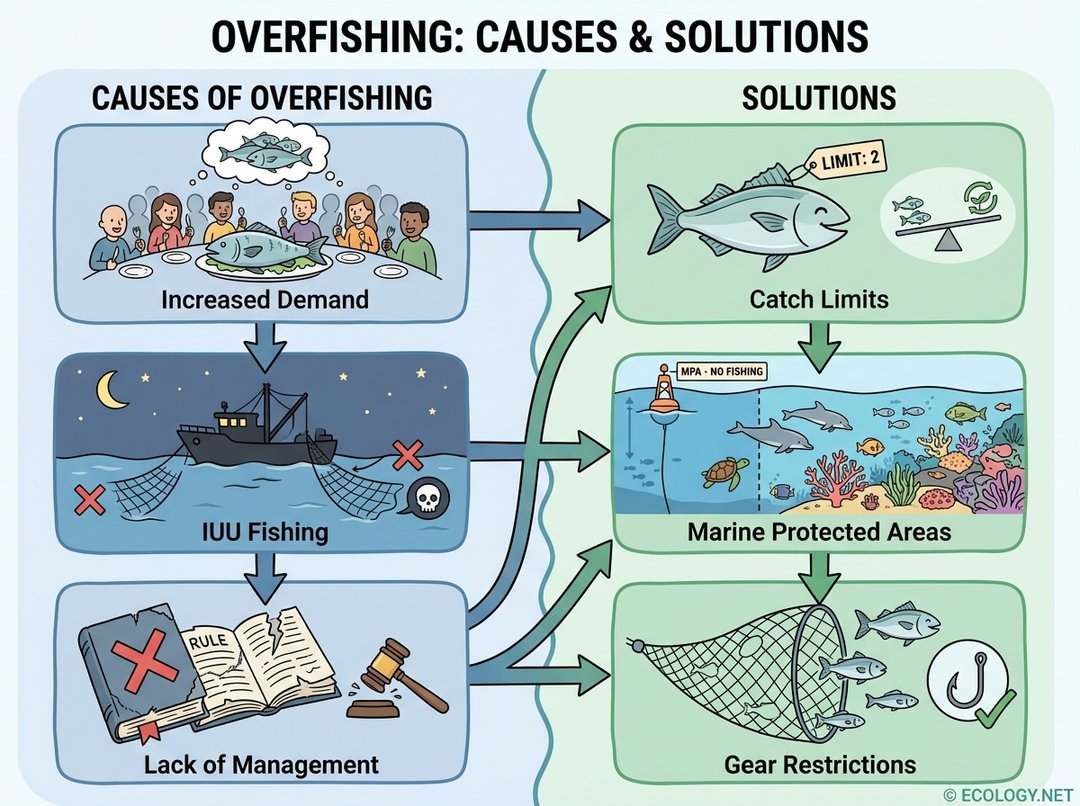

The causes of overfishing are multifaceted, stemming from a complex interplay of economic, social, technological, and political factors.

Increased Global Demand

The global population continues to grow, and with it, the demand for seafood. As incomes rise in many parts of the world, so does the consumption of fish and shellfish. This escalating demand puts immense pressure on finite marine resources.

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing

Often referred to as “pirate fishing,” IUU fishing is a major driver of overfishing. It involves fishing activities that violate national or international laws, are not reported to authorities, or occur in areas without proper management. IUU fishing undermines conservation efforts, distorts markets, and robs legitimate fishers of their livelihoods. It is estimated to account for a significant portion of the global catch.

Lack of Effective Management and Governance

Many fisheries suffer from inadequate management frameworks.

- Weak Regulations: Insufficient catch limits, lax enforcement, or a complete absence of regulations in certain areas allow unchecked exploitation.

- Perverse Subsidies: Government subsidies that reduce the cost of fuel or new vessels can inadvertently encourage overcapacity in fishing fleets, making it economically viable to fish even when stocks are low.

- Data Deficiencies: A lack of accurate data on fish stocks and fishing effort makes it difficult for managers to make informed decisions.

Technological Advancements

Modern fishing technology has dramatically increased the efficiency and scale of fishing operations.

- Advanced Sonar and GPS: These tools allow fishers to locate fish schools with unprecedented precision.

- Larger Vessels: Modern trawlers and factory ships can stay at sea for weeks or months, processing their catch onboard.

- More Efficient Gear: Larger nets, longer lines, and more powerful winches enable the capture of vast quantities of fish.

Management Strategies: What Can Be Done to Prevent Overfishing?

Addressing overfishing requires a comprehensive approach involving international cooperation, robust scientific research, and effective policy implementation. Fortunately, many proven strategies exist.

Catch Limits and Quotas

One of the most direct ways to manage fish stocks is through setting Total Allowable Catch (TAC) limits for specific species. These limits are based on scientific assessments of fish populations and are designed to ensure that enough fish remain to reproduce. Individual fishing quotas (IFQs) allocate a portion of the TAC to individual fishers or vessels, creating an incentive for sustainable practices.

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

MPAs are designated areas of the ocean where human activities, including fishing, are restricted or prohibited.

- No-Take Zones: Within these zones, fish populations can recover, grow larger, and reproduce, acting as “fish banks” that replenish surrounding fishing grounds through spillover effects.

- Habitat Protection: MPAs also protect critical habitats like coral reefs, kelp forests, and spawning grounds, which are essential for the health of the entire ecosystem.

Gear Restrictions and Modifications

Regulating the types of fishing gear used can significantly reduce bycatch and habitat damage.

- Minimum Mesh Sizes: Ensuring nets have mesh sizes large enough to allow juvenile fish to escape, giving them a chance to grow and reproduce.

- Bycatch Reduction Devices (BRDs): Technologies like Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) in shrimp trawls allow sea turtles to escape nets.

- Banning Destructive Gear: Prohibiting practices like bottom trawling in sensitive areas or the use of driftnets.

Certification and Consumer Choice

Empowering consumers to make informed choices can drive demand for sustainably sourced seafood. Organizations like the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) offer certification for fisheries that meet rigorous environmental standards. By choosing seafood with such labels, consumers can support responsible fishing practices.

International Cooperation and Enforcement

Many fish stocks migrate across national boundaries, making international cooperation essential. Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) play a crucial role in setting quotas and managing shared stocks. Strengthening surveillance, monitoring, and enforcement efforts is also vital to combat IUU fishing effectively.

Beyond the Ocean: Socioeconomic Impacts

Overfishing is not just an environmental issue; it has profound socioeconomic consequences.

- Loss of Livelihoods: Fishing communities, particularly in developing nations, rely heavily on healthy fish stocks. Depleted fisheries can lead to job losses, economic hardship, and the erosion of cultural traditions.

- Food Security: For many coastal populations, fish is a primary source of protein. Overfishing can compromise food security, especially for vulnerable communities.

- Economic Instability: The collapse of major fisheries can have ripple effects on national and regional economies, impacting processing plants, distributors, and related industries.

A Call to Action for Ocean Health

Overfishing presents a formidable challenge, but it is not an insurmountable one. By understanding its causes and consequences, and by embracing effective management strategies, humanity can reverse the tide of depletion. The future of our oceans, and indeed our own future, depends on a collective commitment to responsible stewardship. Through informed policy, scientific innovation, and conscious consumer choices, we can ensure that the ocean’s bounty continues to sustain life for generations to come, transforming the silent crisis into a vibrant story of recovery and resilience.