The Adaptable Eaters: Unraveling the World of Omnivores

In the intricate tapestry of life, every creature plays a unique role, defined largely by what it consumes. While some animals are dedicated plant-eaters (herbivores) and others are committed meat-eaters (carnivores), a fascinating group stands apart: the omnivores. These versatile organisms possess the remarkable ability to thrive on both plant and animal matter, making them some of the most adaptable and ecologically significant inhabitants of our planet. Understanding omnivores reveals not just their dietary flexibility, but also their profound impact on ecosystem health and stability.

What Defines an Omnivore?

At its most fundamental, an omnivore is an animal whose natural diet includes a diverse range of both plant and animal material. This broad definition encompasses a vast array of species, from the smallest insects to large mammals, each demonstrating unique adaptations to exploit varied food sources. Unlike the specialized diets of herbivores or carnivores, omnivores possess a generalist approach to feeding, allowing them to capitalize on whatever resources are available in their environment. This dietary flexibility is a cornerstone of their survival and success.

The Anatomy of an Adaptable Eater

The ability to consume and digest both plants and animals requires specific biological adaptations, particularly in dental structure and digestive systems.

Dental Adaptations

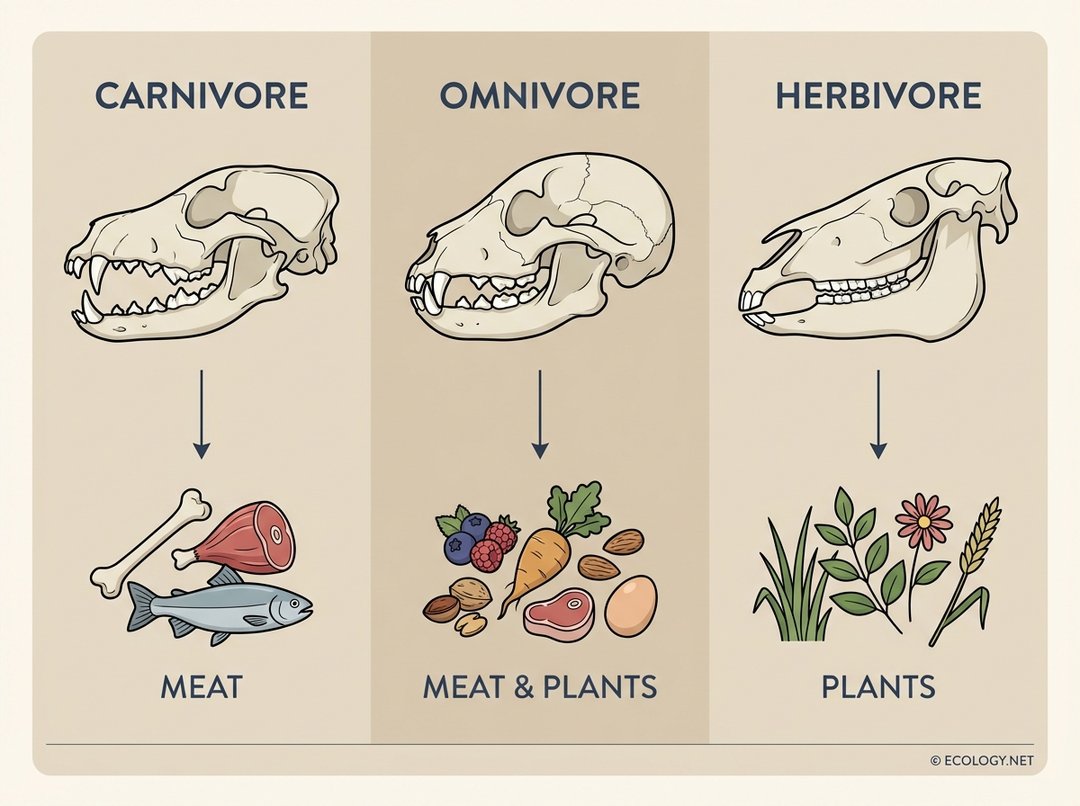

The teeth of an omnivore are a testament to their varied diet, typically featuring a blend of characteristics found in both carnivores and herbivores:

- Incisors: Sharp, chisel-like front teeth, useful for biting into fruits, vegetables, or tearing small pieces of meat.

- Canines: While not as long and pointed as those of a pure carnivore, omnivore canines are present and can be used for grasping, tearing, or piercing, particularly useful for animal prey.

- Molars and Premolars: These back teeth are often flatter and broader than a carnivore’s sharp molars, but not as wide and ridged as a herbivore’s. They are designed for grinding plant material and crushing bones or tougher animal tissues.

Consider the human mouth, a prime example of omnivorous dentition. Our incisors bite into an apple, our canines assist in tearing meat, and our molars grind grains and vegetables. This contrasts sharply with a lion’s purely carnivorous teeth, dominated by large canines and shearing molars, or a cow’s broad, flat molars designed solely for grinding fibrous plants.

Digestive System Flexibility

Beyond teeth, the internal machinery of an omnivore also reflects its dietary versatility. Their digestive tracts are typically intermediate in length and complexity compared to the extremes of herbivores and carnivores:

- Stomach: Often single-chambered, capable of handling both plant and animal matter, though some omnivores may have more complex stomachs.

- Intestines: The length of an omnivore’s intestine falls between the short intestines of carnivores (designed for quick digestion of nutrient-dense meat) and the long, complex intestines of herbivores (necessary for breaking down tough plant fibers). This allows for efficient absorption of nutrients from both types of food.

This anatomical flexibility allows omnivores to extract nutrients from a wide array of food sources, providing a significant survival advantage in environments where specific food types may be scarce or seasonal.

Omnivores in the Ecosystem: More Than Just What They Eat

The ecological role of omnivores extends far beyond their dinner plate. Their ability to consume food from multiple sources positions them uniquely within food webs, making them crucial for energy flow and ecosystem stability.

Trophic Levels and Energy Flow

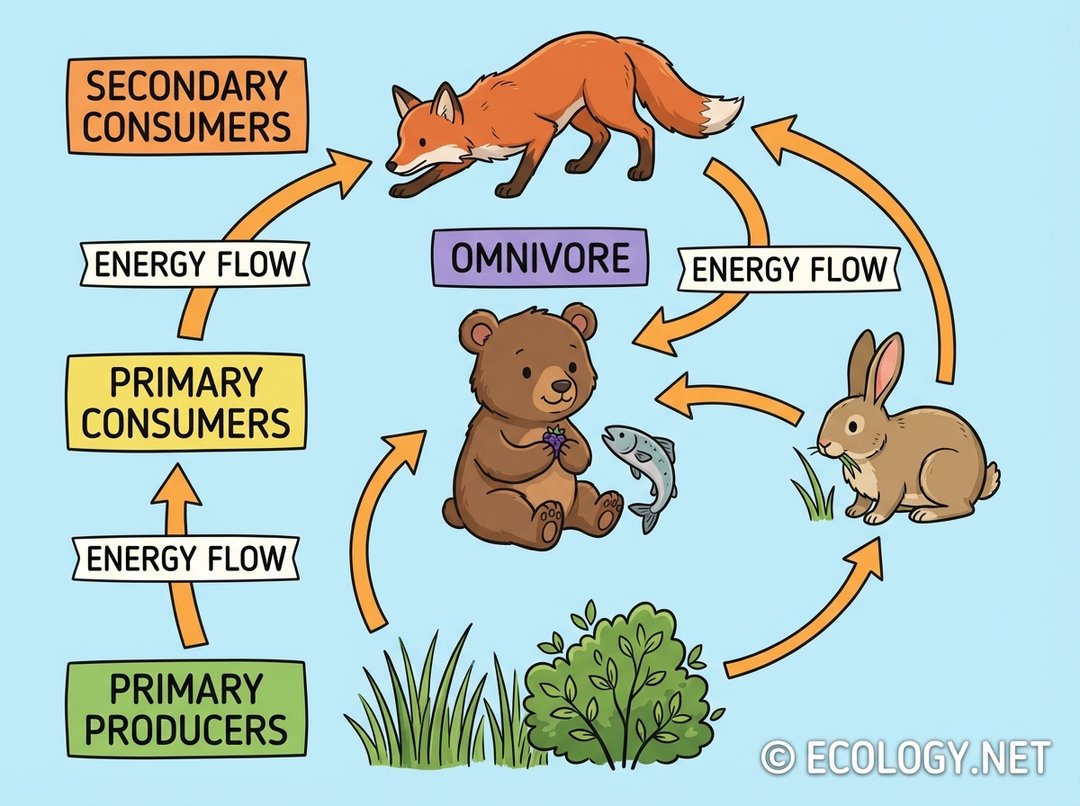

In an ecosystem, organisms are organized into trophic levels based on their feeding position. Primary producers (plants) form the base, followed by primary consumers (herbivores), and then secondary and tertiary consumers (carnivores). Omnivores, however, defy simple categorization.

An omnivore can act as a primary consumer when it eats plants, a secondary consumer when it eats herbivores, and even a tertiary consumer when it preys on carnivores. This multi-level feeding strategy makes them vital conduits for energy transfer throughout the ecosystem.

For example, a bear eating berries is a primary consumer. The same bear eating a salmon (which ate smaller fish, which ate insects, which ate algae) is operating at a much higher trophic level. This flexibility means omnivores can buffer ecosystems against disruptions, adapting their diet if one food source becomes scarce.

Ecological Niche and Adaptability

The broad diet of omnivores allows them to occupy a wide ecological niche, meaning they can thrive in diverse habitats and exploit various resources. This adaptability provides several advantages:

- Reduced Competition: By not relying on a single food type, omnivores face less direct competition for resources compared to highly specialized feeders.

- Survival in Changing Conditions: In environments experiencing seasonal changes, climate shifts, or habitat alteration, omnivores can switch their diet to available foods, increasing their chances of survival. For instance, a fox might primarily hunt rodents in summer but switch to foraging for berries and insects in autumn.

- Pioneer Species: Some omnivores can be among the first species to colonize new or disturbed habitats, thanks to their ability to find sustenance from various sources.

Key Ecological Roles of Omnivores

Beyond their position in the food web, omnivores perform several critical functions that contribute to the health and resilience of ecosystems.

Seed Dispersal and Ecosystem Health

Many omnivores consume fruits, berries, and nuts as part of their plant-based diet. When they digest the fleshy parts of these foods, the seeds often pass through their digestive tracts unharmed and are then deposited in new locations, often far from the parent plant. This process, known as seed dispersal, is fundamental for:

- Plant Propagation: Spreading seeds allows plants to colonize new areas, increasing their population and genetic diversity.

- Forest Regeneration: In forested ecosystems, omnivores like bears and birds are crucial for the regeneration of plant communities after disturbances.

- Maintaining Biodiversity: Effective seed dispersal helps maintain a rich variety of plant species, which in turn supports a wider array of animal life.

Scavenging and Nutrient Cycling

A significant, though often overlooked, role of many omnivores is scavenging. They consume carrion (the carcasses of dead animals) and decaying plant matter, preventing the buildup of organic waste and facilitating the return of essential nutrients to the soil. This process is vital for:

- Nutrient Recycling: By breaking down organic material, omnivores help convert complex molecules into simpler forms that can be reabsorbed by plants, completing the nutrient cycle.

- Disease Prevention: Removing carcasses from the environment can help limit the spread of diseases that might otherwise proliferate.

- Ecosystem Clean-up: Scavengers act as nature’s clean-up crew, maintaining the overall health and aesthetics of an ecosystem. Raccoons, crows, and even some insects are excellent examples of omnivorous scavengers.

Population Control

By preying on both herbivores and smaller carnivores, omnivores can exert a regulatory influence on various animal populations. This helps prevent any single species from overpopulating and destabilizing the ecosystem. For example, a coyote might hunt rabbits (herbivores) and also consume insects or fruits, thereby influencing multiple trophic levels simultaneously.

Examples of Omnivores Across the Animal Kingdom

The omnivorous diet is a successful strategy adopted by a vast array of species across different classes of the animal kingdom.

- Mammals:

- Bears: Grizzly bears and black bears are classic examples, consuming berries, roots, insects, fish, and small mammals.

- Raccoons: Famous for their opportunistic feeding, eating fruits, nuts, insects, eggs, and small vertebrates.

- Pigs: Wild boars and domestic pigs will eat almost anything, from roots and fungi to insects, eggs, and carrion.

- Humans: Our species is perhaps the most successful omnivore, with a diet that has historically adapted to nearly every environment on Earth.

- Foxes: While often seen as predators, many fox species supplement their diet of rodents and birds with fruits, berries, and insects.

- Badgers: These burrowing mammals consume worms, insects, small mammals, and plant matter like roots and fruits.

- Birds:

- Crows and Ravens: Highly intelligent birds that eat seeds, fruits, insects, eggs, nestlings, and carrion.

- Chickens: Domestic chickens readily consume grains, insects, worms, and greens.

- Gulls: Coastal birds that eat fish, crustaceans, eggs, and human refuse.

- Ostriches: While primarily herbivorous, they will also consume insects and small reptiles.

- Reptiles and Amphibians:

- Some Turtles: Many freshwater turtles are omnivorous, eating aquatic plants, insects, and small fish.

- Skinks: Some species of these lizards consume both insects and plant material.

- Fish:

- Piranhas: While often portrayed as pure carnivores, many piranha species are omnivorous, consuming fruits, seeds, and aquatic vegetation alongside fish.

- Carp: These freshwater fish feed on aquatic plants, insects, and small invertebrates.

- Insects:

- Cockroaches: Notorious for their ability to eat almost anything organic.

- Ants: Many ant species are omnivorous, foraging for seeds, nectar, fungi, and other insects.

The Human Omnivore: A Unique Case Study

Humans stand as a prime example of successful omnivory. Our evolutionary history is marked by a flexible diet that allowed our ancestors to adapt to diverse environments, from savannas to forests and eventually to every continent. The ability to consume both plant and animal matter provided crucial nutritional advantages, supporting brain development and enabling survival through periods of food scarcity. Today, human dietary choices continue to reflect this omnivorous heritage, with cultures around the world incorporating a vast array of plant and animal foods. This adaptability has been a key factor in our species’ global dominance, but it also comes with the responsibility of understanding our impact on the ecosystems that sustain us.

Conclusion

Omnivores are truly the generalists of the animal kingdom, embodying adaptability and resilience. Their unique anatomical features, particularly their versatile teeth and digestive systems, allow them to exploit a diverse range of food sources. This dietary flexibility not only ensures their own survival but also positions them as indispensable components of healthy ecosystems. From connecting multiple trophic levels and facilitating energy flow to dispersing seeds and recycling nutrients, omnivores play multifaceted roles that are critical for maintaining ecological balance and biodiversity. Their story is a powerful reminder of the intricate and interconnected nature of life on Earth, where adaptability often holds the key to thriving.