Imagine Earth as a magnificent, self-sustaining machine. For this machine to run smoothly, its vital components must be constantly reused and recycled. In the grand scheme of our planet’s ecosystems, these vital components are known as nutrients, and their continuous journey through various parts of the environment is what scientists call nutrient cycles. These intricate processes are the very essence of life, ensuring that the building blocks for all organisms are perpetually available, transforming and moving from the air to the soil, through living beings, and back again.

Without these tireless recycling systems, life as we know it would grind to a halt. Essential elements like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus would remain locked away, inaccessible to the plants and animals that depend on them for growth, energy, and survival. Understanding nutrient cycles is not just an academic exercise; it is key to comprehending the fundamental workings of our planet and recognizing the profound impact human activities have on these delicate, life-sustaining balances.

What are Nutrient Cycles? The Earth’s Grand Recycling System

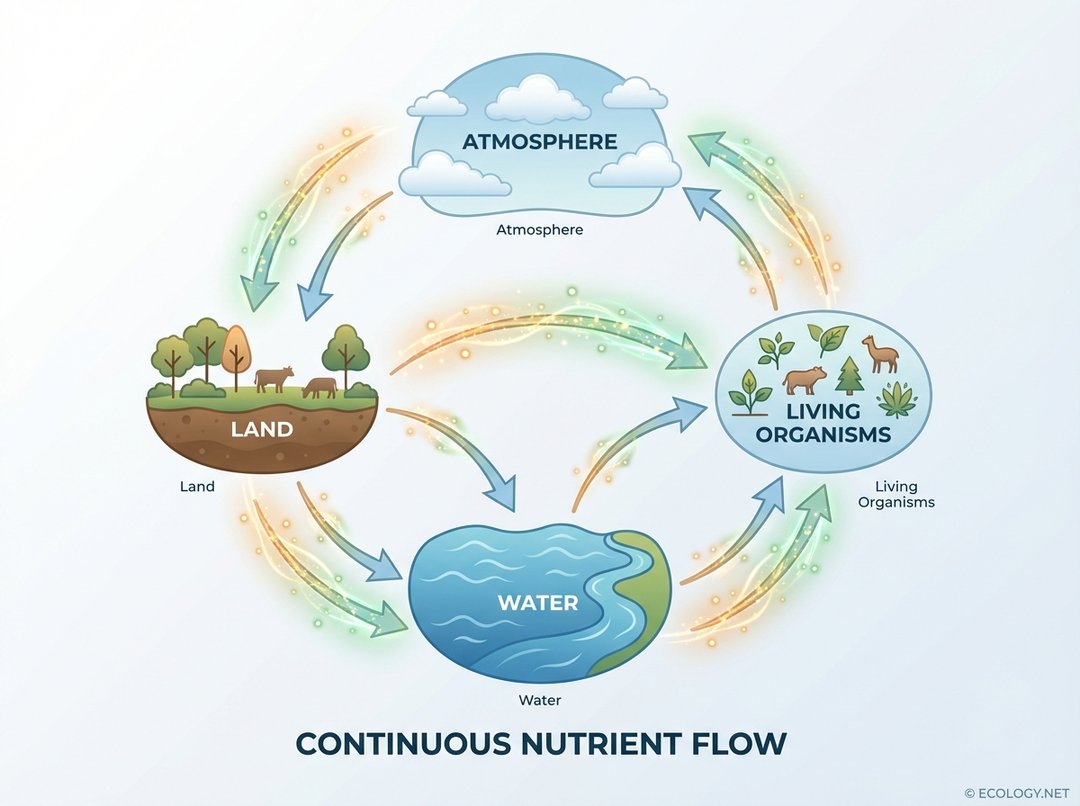

At its core, a nutrient cycle describes the movement of a specific nutrient through the living and non-living components of an ecosystem. These cycles are biogeochemical cycles, meaning they involve biological (living organisms), geological (rocks, soil), and chemical (water, air) processes. Think of them as Earth’s sophisticated circulatory system, where nutrients are the lifeblood, constantly flowing and transforming.

Essential nutrients are chemical elements that organisms need to grow, reproduce, and maintain their metabolic functions. These include macronutrients, required in large amounts (like carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur), and micronutrients, needed in smaller quantities (like iron, zinc, copper). While the specific pathways vary for each nutrient, the general principle remains the same: nutrients are never truly lost; they simply change form and location.

The journey of a nutrient typically involves several key reservoirs or “pools” where it can be stored for varying periods. These reservoirs include:

- Atmosphere: The air surrounding Earth, a major reservoir for gases like nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

- Hydrosphere: All the water on Earth, including oceans, rivers, lakes, and groundwater, which dissolve and transport many nutrients.

- Lithosphere: The Earth’s crust, including rocks and soil, which store vast amounts of nutrients like phosphorus and calcium.

- Biosphere: All living organisms, from microscopic bacteria to giant whales, which incorporate nutrients into their tissues.

The movement of nutrients between these reservoirs is driven by a combination of physical, chemical, and biological processes. For example, plants absorb nutrients from the soil, animals consume plants, and decomposers return nutrients to the soil when organisms die. This continuous loop ensures that resources are perpetually available for new life.

Delving Deeper: Specific Nutrient Cycles

While the general concept of nutrient cycling is universal, each essential element has its own unique and fascinating journey. Let’s explore some of the most critical cycles that underpin all life on Earth.

The Carbon Cycle: The Backbone of Life

Carbon is the fundamental building block of all organic molecules, from the sugars that fuel our bodies to the DNA that carries our genetic code. The carbon cycle describes the movement of carbon atoms through Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, land, and living organisms.

- Atmospheric Carbon: Carbon exists primarily as carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere.

- Photosynthesis: Plants, algae, and some bacteria absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere (or dissolved in water) and convert it into organic compounds (sugars) using sunlight. This is how carbon enters the living world.

- Respiration: All living organisms, including plants and animals, release CO₂ back into the atmosphere as they break down organic compounds for energy.

- Decomposition: When plants and animals die, decomposers (bacteria and fungi) break down their organic matter, releasing carbon back into the soil and atmosphere.

- Oceanic Carbon: Oceans absorb a significant amount of atmospheric CO₂, which dissolves to form carbonic acid. Marine organisms use dissolved carbon to build shells and skeletons.

- Geological Carbon: Over millions of years, dead organic matter can be buried and transformed into fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas) or sedimentary rocks like limestone, storing carbon for vast periods.

- Combustion: The burning of organic matter, including fossil fuels and biomass, releases large amounts of CO₂ back into the atmosphere.

The carbon cycle is a delicate balance, crucial for regulating Earth’s climate. Small changes in its balance can have significant global consequences.

The Nitrogen Cycle: Life’s Essential Protein Builder

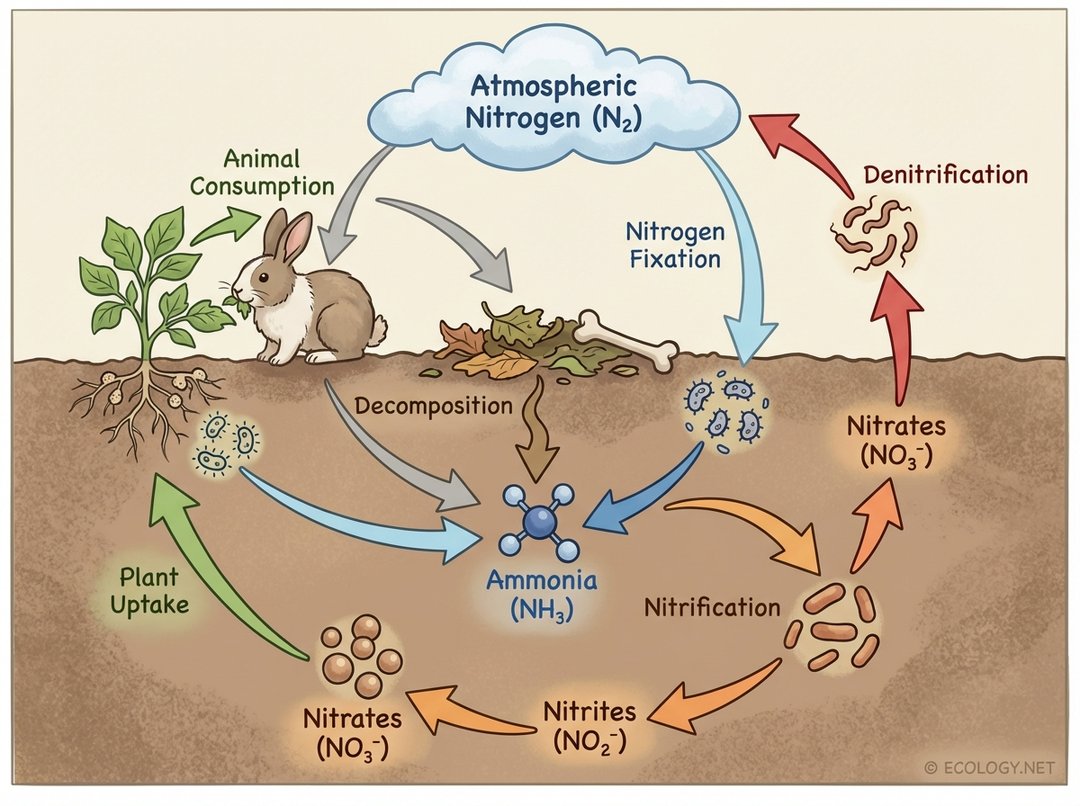

Nitrogen is a critical component of proteins, nucleic acids (DNA and RNA), and chlorophyll. Although nitrogen gas (N₂) makes up about 78% of Earth’s atmosphere, most organisms cannot directly use it in this form. The nitrogen cycle is particularly complex because it involves numerous transformations, largely facilitated by microorganisms.

Here are the key steps:

- Nitrogen Fixation: Atmospheric N₂ is converted into ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium (NH₄⁺), a usable form for plants. This vital process is carried out by:

- Biological Fixation: Specialized bacteria (e.g., Rhizobium in legume root nodules, free-living bacteria in soil) convert N₂ into ammonia.

- Atmospheric Fixation: Lightning provides energy to convert N₂ into nitrates (NO₃⁻).

- Industrial Fixation: Human processes, like the Haber-Bosch process, create ammonia for fertilizers.

- Nitrification: Ammonia (NH₃) or ammonium (NH₄⁺) is converted into nitrites (NO₂⁻) and then nitrates (NO₃⁻) by different groups of nitrifying bacteria in the soil. Nitrates are the primary form of nitrogen absorbed by plants.

- Assimilation: Plants absorb nitrates and ammonium from the soil and incorporate them into their organic molecules (proteins, DNA). Animals then obtain nitrogen by eating plants or other animals.

- Ammonification (Decomposition): When plants and animals die, or when animals excrete waste, decomposers break down the organic nitrogen compounds, releasing ammonia or ammonium back into the soil.

- Denitrification: Under anaerobic (low oxygen) conditions, denitrifying bacteria convert nitrates back into nitrogen gas (N₂), which is then released into the atmosphere, completing the cycle.

The nitrogen cycle highlights the indispensable role of bacteria in mediating nutrient availability for all other life forms.

The Phosphorus Cycle: The Energy Currency

Phosphorus is essential for DNA, RNA, ATP (the energy currency of cells), and cell membranes, as well as for bones and teeth in animals. Unlike carbon and nitrogen, the phosphorus cycle does not have a significant atmospheric gaseous phase; it primarily cycles through rocks, soil, water, and living organisms.

- Weathering: Phosphorus is released from rocks through weathering and erosion, entering the soil and water as phosphate (PO₄³⁻).

- Uptake: Plants absorb dissolved phosphate from the soil or water.

- Consumption: Animals obtain phosphorus by eating plants or other animals.

- Decomposition: When organisms die, decomposers return organic phosphorus to the soil and water, where it is converted back into inorganic phosphate.

- Sedimentation: Some phosphate can settle at the bottom of oceans and lakes, forming new sedimentary rocks over geological timescales, effectively locking it away for millions of years before it is uplifted and weathered again.

The slow geological processes make the phosphorus cycle much slower than the carbon or nitrogen cycles, and phosphorus is often a limiting nutrient in many ecosystems.

The Water Cycle: The Great Transporter

While not a nutrient itself, the water cycle (or hydrologic cycle) is intimately linked to all nutrient cycles. Water acts as the primary medium for dissolving and transporting nutrients. It carries dissolved minerals from rocks into soil, moves nutrients through ecosystems via rivers and streams, and facilitates the uptake of nutrients by plants. Without the continuous movement of water, the other nutrient cycles would largely cease to function.

The Interconnectedness of Cycles

It is crucial to understand that these cycles do not operate in isolation. They are deeply interconnected, forming a complex web of interactions that sustain life. For example:

- The carbon cycle influences the nitrogen cycle through the availability of organic matter for decomposers, which are vital for nitrogen transformations.

- The nitrogen and phosphorus cycles are linked because both are essential for plant growth, and their availability can limit primary productivity, thereby affecting the carbon cycle’s photosynthetic rates.

- Water is the universal solvent, facilitating the movement of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus compounds through soil, plants, and aquatic systems.

Disrupting one cycle inevitably has ripple effects on the others, highlighting the delicate balance of Earth’s natural systems.

Human Impact: Disrupting Earth’s Delicate Balance

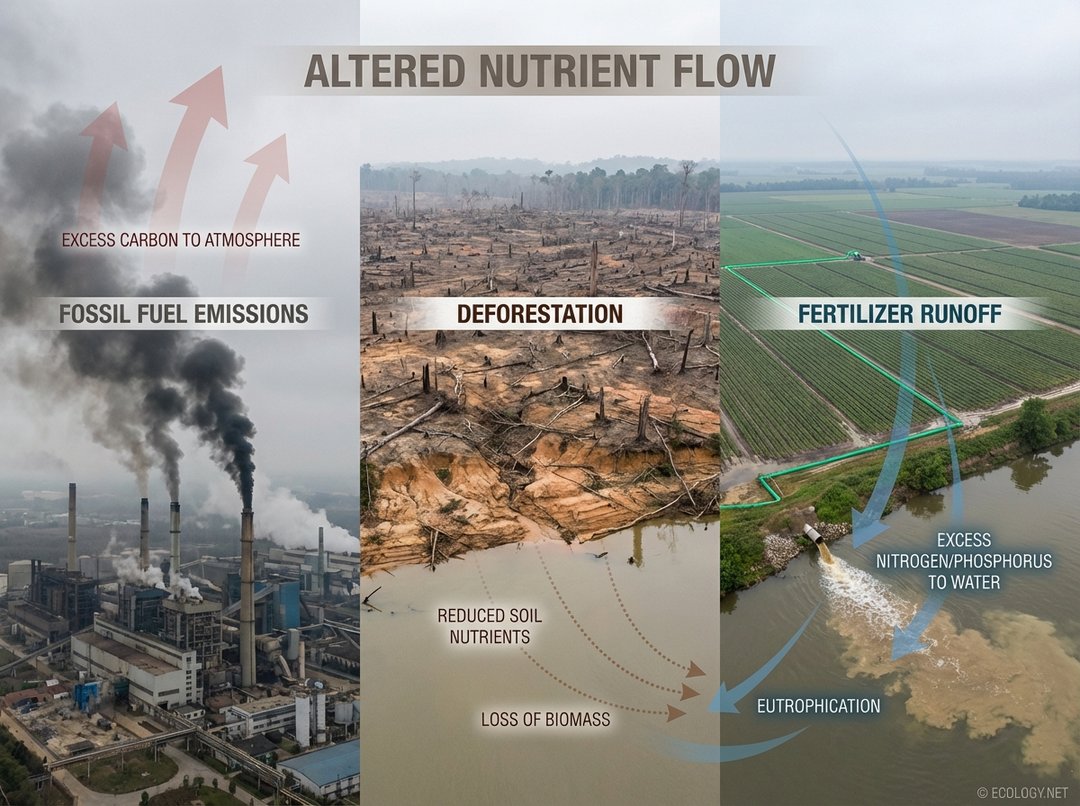

For millennia, nutrient cycles operated in a relatively stable equilibrium. However, in recent centuries, human activities have dramatically altered these fundamental processes, leading to significant environmental challenges.

Carbon Cycle Disruptions:

- Fossil Fuel Emissions: The burning of coal, oil, and natural gas for energy releases vast amounts of stored carbon (as CO₂) into the atmosphere, far exceeding natural rates. This excess CO₂ is a primary driver of climate change and ocean acidification.

- Deforestation: Forests act as major carbon sinks, absorbing CO₂ through photosynthesis. Clearing forests for agriculture or development releases stored carbon back into the atmosphere and reduces the planet’s capacity to absorb future emissions.

Nitrogen Cycle Disruptions:

- Agricultural Fertilizers: The industrial production of nitrogen fertilizers (using the Haber-Bosch process) and their widespread application in agriculture has more than doubled the amount of reactive nitrogen entering terrestrial ecosystems.

- Runoff and Eutrophication: Excess nitrogen from fertilizers can leach into groundwater and run off into rivers and coastal waters. This nutrient enrichment, known as eutrophication, can lead to algal blooms, oxygen depletion (hypoxia), and “dead zones” that devastate aquatic life.

- Atmospheric Pollution: Nitrogen oxides (NOx) released from burning fossil fuels contribute to smog, acid rain, and greenhouse gas emissions.

Phosphorus Cycle Disruptions:

- Mining and Fertilizers: Phosphorus is mined from rock deposits and used extensively in agricultural fertilizers. This accelerates the natural weathering process and introduces large quantities of phosphorus into ecosystems.

- Runoff and Eutrophication: Similar to nitrogen, excess phosphorus from agricultural runoff and wastewater discharge contributes to eutrophication in freshwater and coastal marine environments.

- Limited Resource: Unlike nitrogen, which is abundant in the atmosphere, phosphorus is a finite resource. Its concentrated use and loss to sedimentation raise concerns about long-term availability.

These human-induced alterations have profound consequences, including global warming, loss of biodiversity, degradation of water quality, and disruption of ecosystem services.

Protecting Our Planet’s Lifelines: What Can Be Done?

Addressing the disruptions to nutrient cycles requires a multi-faceted approach, combining scientific understanding with policy changes and individual actions.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Implementing practices like precision farming (applying fertilizers only where and when needed), cover cropping, crop rotation, and organic farming can reduce nutrient runoff and improve soil health.

- Renewable Energy: Transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources (solar, wind, hydro) is crucial for reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change.

- Forest Conservation and Reforestation: Protecting existing forests and planting new ones helps sequester carbon and maintain healthy ecosystem functions.

- Wastewater Treatment: Improving wastewater treatment facilities to remove nitrogen and phosphorus before discharge can significantly reduce aquatic pollution.

- Dietary Choices: Reducing consumption of resource-intensive foods, particularly those with a high carbon and nitrogen footprint, can contribute to a more sustainable food system.

- Consumer Awareness: Educating the public about the importance of nutrient cycles and the impact of human activities empowers individuals to make more environmentally conscious decisions.

Conclusion

Nutrient cycles are the invisible engines that power our planet’s ecosystems, orchestrating the continuous flow of life-sustaining elements. From the vast expanse of the atmosphere to the microscopic world within the soil, these cycles demonstrate Earth’s remarkable capacity for self-renewal. However, human activities have introduced unprecedented pressures, altering these fundamental processes with far-reaching consequences for environmental health and human well-being.

By understanding the intricate dance of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and water, we gain a deeper appreciation for the interconnectedness of all life. More importantly, this knowledge empowers us to become better stewards of our planet, inspiring innovative solutions and fostering a commitment to practices that restore balance and ensure the continued vitality of Earth’s grand recycling system for generations to come.