In the intricate tapestry of life on Earth, relationships between species are constantly being woven. From fierce competition to one-sided benefits, the natural world is a stage for countless interactions. Among the most fascinating and fundamental of these is mutualism, a partnership where both parties walk away better off. Far from a rare occurrence, mutualism is a driving force behind biodiversity, ecosystem stability, and even the evolution of life itself.

What is Mutualism? A Symbiotic Win-Win

At its core, mutualism describes an ecological interaction between two or more species where each participant benefits from the activity of the other. This reciprocal advantage distinguishes mutualism from other forms of symbiosis, where the outcomes can vary widely.

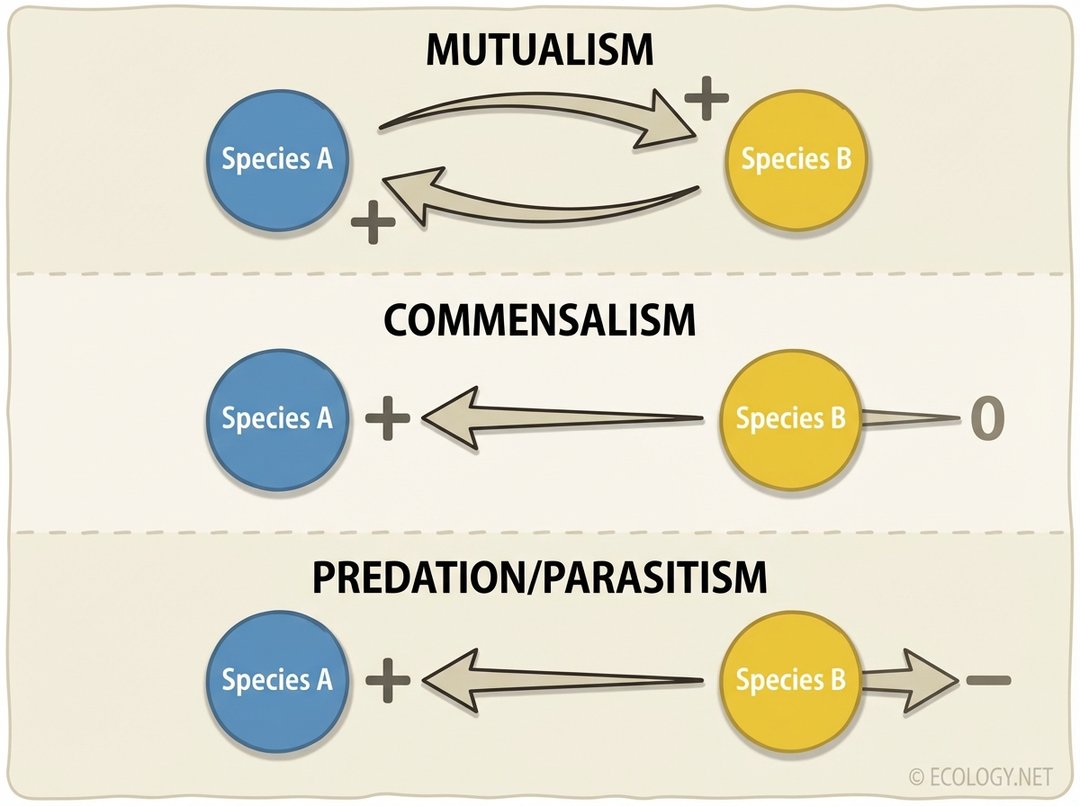

Consider the spectrum of ecological interactions:

- Predation: One species benefits (predator), the other is harmed (prey).

- Parasitism: One species benefits (parasite), the other is harmed (host).

- Commensalism: One species benefits, the other is unaffected.

- Competition: Both species are harmed by the interaction, as they vie for limited resources.

- Mutualism: Both species benefit from the interaction.

This concept of reciprocal benefit is crucial for understanding how complex ecosystems function and thrive. It is not merely a passive coexistence but an active exchange of resources, services, or protection that enhances the survival and reproduction of all involved partners.

The Many Faces of Mutualism: Obligate vs. Facultative

Mutualistic relationships are not all created equal. The degree of dependency between the partners can vary significantly, leading to two primary classifications: obligate and facultative mutualism.

Obligate Mutualism: An Indispensable Partnership

Obligate mutualism describes a relationship where one or both species cannot survive or reproduce without the other. These partnerships are so tightly intertwined that the absence of one partner spells doom for the other. Such relationships often evolve over long periods, leading to highly specialized adaptations.

A classic example is the yucca plant and the yucca moth. The yucca moth is the sole pollinator of the yucca flower, actively collecting pollen and depositing it on the stigma. In return, the moth lays its eggs inside the yucca flower, and its larvae feed on a small number of the developing seeds. Without the moth, the yucca cannot reproduce; without the yucca, the moth has no place to lay its eggs or food for its young.

Facultative Mutualism: A Beneficial Choice

In contrast, facultative mutualism is a relationship where both species benefit, but neither is entirely dependent on the other for survival. The partners can live independently, but their association provides a significant advantage, making the interaction beneficial but not strictly necessary.

Many pollinator relationships fall into this category. Bees, for instance, visit a wide variety of flowers for nectar and pollen, aiding in the reproduction of numerous plant species. While a specific bee species might prefer certain flowers, it can typically survive by foraging on others if its preferred plant is unavailable. Similarly, many plants are pollinated by multiple insect species, ensuring their reproduction even if one pollinator is absent.

Beyond Dependency: Resource and Service Exchanges

Mutualistic relationships can also be categorized by what is exchanged:

- Resource-Resource Mutualism: Both partners exchange resources. For example, mycorrhizal fungi provide plants with water and nutrients, while plants provide fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis.

- Service-Resource Mutualism: One partner provides a service, and the other provides a resource. Pollination is a prime example, where insects provide the service of pollen transfer in exchange for nectar (a resource).

- Service-Service Mutualism: Both partners provide a service. A less common but intriguing category, such as the relationship between certain anemonefish and sea anemones, where the fish gains protection and the anemone is cleaned and defended from predators.

Iconic Examples of Mutualism in Action

The natural world abounds with stunning examples of mutualism, showcasing its diverse forms and profound impact.

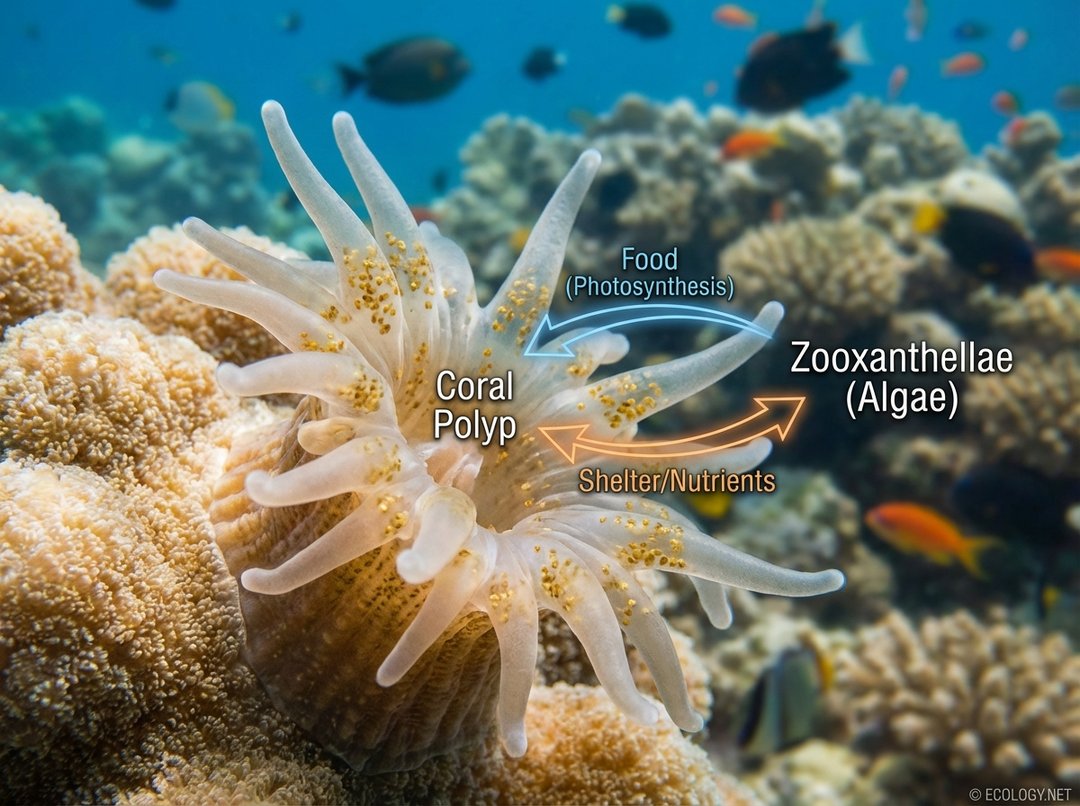

Coral Reefs: The Foundation of Ocean Biodiversity

Perhaps one of the most visually striking examples of obligate mutualism occurs in coral reefs. Coral polyps, tiny marine animals, form an indispensable partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The zooxanthellae live within the coral tissues, performing photosynthesis and providing the coral with up to 90% of its energy needs in the form of sugars. In return, the coral provides the algae with a protected environment and compounds necessary for photosynthesis, such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen. This partnership is so vital that without zooxanthellae, corals cannot thrive, leading to coral bleaching and the eventual collapse of these incredibly diverse ecosystems.

Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plants: The Underground Network

Beneath our feet, a vast and ancient mutualistic network thrives. Mycorrhizal fungi form associations with the roots of approximately 90% of all plant species. The fungi extend their hyphae far into the soil, vastly increasing the plant’s surface area for absorbing water and essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. In exchange, the plant supplies the fungi with carbohydrates, the products of photosynthesis. This partnership is critical for plant growth, especially in nutrient-poor soils, and plays a fundamental role in global nutrient cycling.

Pollinators and Flowering Plants: A Dance of Life

The vibrant colors and sweet scents of flowers are not just for human enjoyment; they are advertisements for pollinators. Bees, butterflies, birds, bats, and even some mammals engage in mutualistic relationships with flowering plants. The pollinators receive nectar or pollen as food, while the plants benefit from the transfer of pollen, enabling fertilization and seed production. This interaction is a cornerstone of terrestrial ecosystems, supporting food webs and agricultural productivity worldwide.

Cleaner Fish and Larger Marine Life: A Hygienic Alliance

In the ocean, certain small fish and shrimp act as “cleaner organisms,” removing parasites, dead skin, and debris from larger fish, turtles, and even sharks. The cleaner gains a meal, while the larger animal benefits from improved health and hygiene. This is a fascinating example of a service-service mutualism, often observed at designated “cleaning stations” on coral reefs.

Ants and Acacias: A Guarded Friendship

Some acacia trees in Central and South America have evolved a remarkable mutualistic relationship with aggressive ants. The acacia provides the ants with shelter in its hollow thorns and food in the form of nectar from extrafloral nectaries and protein-rich Beltian bodies. In return, the ants vigorously defend the tree against herbivores, both insects and larger mammals, and even clear competing vegetation from around the tree’s base. This protection is so effective that acacias with ant partners grow significantly faster and suffer less damage than those without.

The Human Gut Microbiome: Our Inner Ecosystem

Even within our own bodies, mutualism is at play. Trillions of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms reside in our digestive tracts, forming what is known as the gut microbiome. Many of these microbes aid in the digestion of complex carbohydrates that our own enzymes cannot break down, producing essential vitamins (like K and B vitamins), and training our immune system. In return, we provide them with a stable environment and a constant supply of food. This internal mutualism is vital for human health and well-being.

The Ecological Significance of Mutualism

Mutualistic relationships are far more than isolated curiosities; they are fundamental to the structure and function of ecosystems globally.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: Mutualism often underpins the incredible diversity found in ecosystems like coral reefs and rainforests. The intricate web of dependencies allows for a greater number of species to coexist.

- Ecosystem Stability: By facilitating nutrient cycling, pollination, and defense mechanisms, mutualistic interactions contribute to the resilience and stability of ecosystems in the face of environmental change.

- Nutrient Cycling: From mycorrhizal fungi enhancing nutrient uptake in plants to nitrogen-fixing bacteria in legume roots, mutualism drives critical biogeochemical cycles that sustain life.

- Evolutionary Drivers: The co-evolutionary dance between mutualistic partners can lead to remarkable adaptations, shaping the morphology, physiology, and behavior of species over geological timescales.

- Ecosystem Services: Many vital services that ecosystems provide to humanity, such as food production (through pollination), clean water (through healthy plant communities), and climate regulation, are direct outcomes of mutualistic interactions.

Challenges and Nuances in Mutualistic Relationships

While mutualism is defined by reciprocal benefits, these relationships are not always perfectly harmonious or static. They are dynamic and subject to evolutionary pressures.

The Threat of Cheating

In any mutualistic system, there is always the potential for one partner to “cheat” by receiving benefits without providing adequate returns. For example, some plants produce nectar but no pollen, attracting pollinators without offering a reproductive service. However, ecosystems often have mechanisms to detect and penalize cheaters, maintaining the integrity of the mutualism over time.

Context Dependency

The nature of a symbiotic relationship can sometimes shift depending on environmental conditions. What is mutualistic in one context might become parasitic or commensal in another. For instance, some fungi that are mutualistic with plants in nutrient-poor soils can become parasitic in nutrient-rich conditions, where the plant no longer needs the fungal assistance as much.

Evolutionary Arms Races

Even in mutualism, an ongoing evolutionary “arms race” can occur as each partner evolves to maximize its own benefit from the interaction. This can lead to increasingly specialized adaptations and a delicate balance that is constantly being refined.

Mutualism reminds us that cooperation, not just competition, is a powerful engine of evolution and a cornerstone of ecological success.

Conclusion: The Power of Partnership

Mutualism stands as a testament to the power of cooperation in the natural world. From the microscopic exchanges within a coral polyp to the grand spectacle of a pollinator garden, these win-win partnerships illustrate how diverse life forms can thrive by working together. Understanding mutualism is not just an academic exercise; it provides crucial insights into how ecosystems function, how biodiversity is maintained, and how we might better manage and conserve the planet’s invaluable natural resources. As we continue to unravel the complexities of life, the story of mutualism offers a compelling narrative of interdependence, resilience, and the enduring success of collaboration.