In the intricate tapestry of life, every organism, from the smallest bacterium to the largest whale, strives to grow, reproduce, and thrive. Yet, this journey is rarely a smooth ascent. Instead, it is a constant negotiation with the environment, a delicate balance where success often hinges on the availability of essential resources. This fundamental ecological principle is encapsulated by the concept of “limiting factors.”

Understanding limiting factors is not merely an academic exercise for ecologists. It is a crucial lens through which we can comprehend everything from the lushness of a rainforest to the barrenness of a desert, the success of a crop yield, or the decline of an endangered species. It reveals the invisible hand that shapes populations, communities, and entire ecosystems.

What Are Limiting Factors? The Ecological Bottleneck

At its core, a limiting factor is any environmental condition or resource that restricts the growth, abundance, or distribution of an organism or population. Imagine a chain: its strength is determined not by its strongest link, but by its weakest. Similarly, an organism’s potential for growth and survival is capped by the resource that is in shortest supply, even if all other resources are abundant.

This idea was famously formalized by agricultural chemist Justus von Liebig in the mid-19th century, known as Liebig’s Law of the Minimum. He observed that plant growth was not determined by the total amount of available nutrients, but by the nutrient that was the most scarce. This principle extends far beyond agriculture, applying to all forms of life and all types of resources.

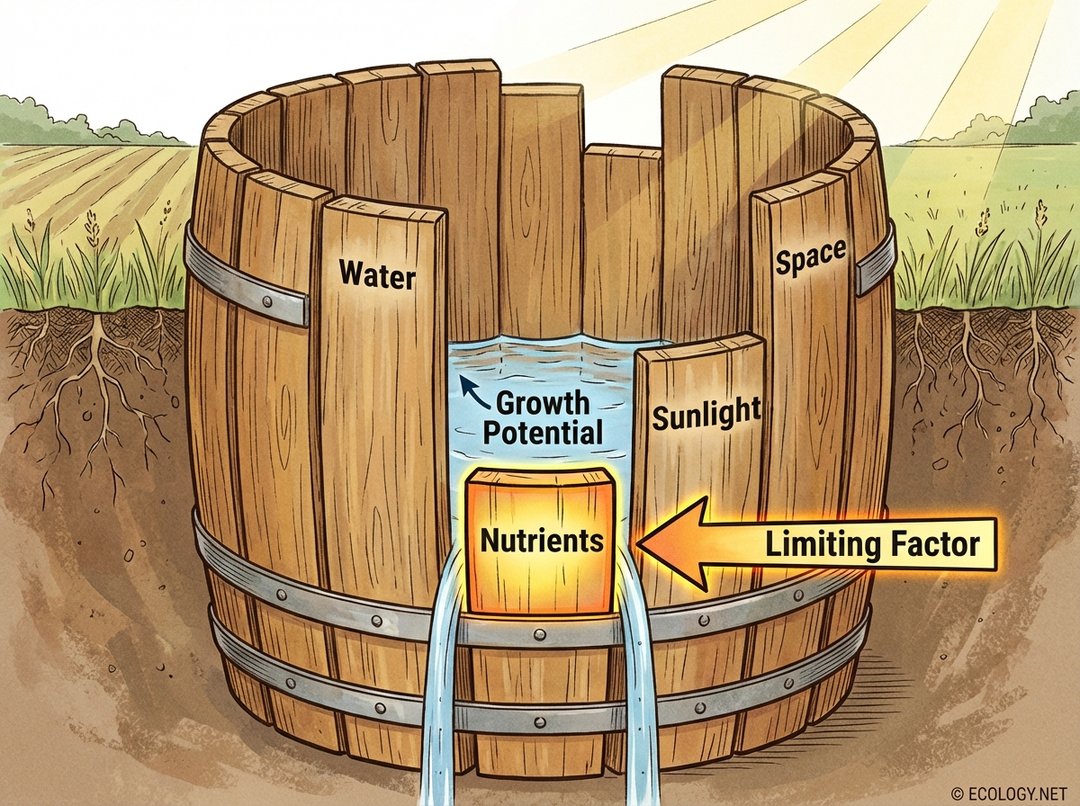

To visualize this, consider Liebig’s famous barrel analogy:

Imagine a barrel made of staves of different heights. The water level that the barrel can hold is determined by the shortest stave, not the average height of all staves. In this analogy, the water represents an organism’s growth potential, and each stave represents a different essential resource, such as water, sunlight, nutrients, or space. The shortest stave, therefore, is the limiting factor, dictating the maximum possible growth or population size, regardless of how plentiful other resources might be.

The Diverse Cast of Limiting Factors

Limiting factors can be broadly categorized into two main types: abiotic (non-living) and biotic (living).

Abiotic Limiting Factors

These are the physical and chemical components of an ecosystem that can restrict life. They are often the most intuitive to grasp.

- Light: For photosynthetic organisms like plants and algae, sunlight is the ultimate energy source. In deep oceans, dense forests, or even heavily shaded ponds, light can become a critical limiting factor.

- Water: Essential for all life, water availability dictates the distribution of species across the globe. Deserts are classic examples where water scarcity severely limits plant and animal life. Conversely, too much water, leading to waterlogged soils, can also be limiting for terrestrial plants.

- Temperature: Every organism has an optimal temperature range for its metabolic processes. Extremes of heat or cold can limit survival and reproduction. Think of polar bears adapted to frigid Arctic temperatures or cacti thriving in scorching deserts.

- Nutrients: From nitrogen and phosphorus in soils and water to trace minerals, the availability of essential nutrients can profoundly impact growth. In many aquatic environments, phosphorus or nitrogen often act as limiting factors for algal growth.

- Space: Physical space for nesting, foraging, or simply existing can become a limiting factor, especially in crowded populations or confined habitats. Coral reefs, for instance, are highly productive but limited by available substrate for new coral polyps.

- pH and Salinity: The acidity or alkalinity of soil and water, and the concentration of salts, can be critical. Most organisms have narrow tolerance ranges for these factors.

Biotic Limiting Factors

These factors arise from interactions with other living organisms within an ecosystem.

- Competition: When multiple organisms require the same limited resource, they compete. This can be competition between individuals of the same species (intraspecific) or different species (interspecific). Intense competition can limit population sizes.

- Predation: The presence of predators can limit the population size of prey species. For example, a high wolf population might limit the deer population in a given area.

- Disease and Parasitism: Outbreaks of disease or heavy parasitic loads can significantly reduce population numbers, acting as a powerful limiting factor.

- Herbivory: For plants, intense grazing by herbivores can limit their growth and distribution.

- Lack of Mates: In very sparse populations, finding a mate can become a limiting factor for reproduction.

The Dynamic Nature of Limitation

It is crucial to understand that limiting factors are not static. They can change over time, vary by location, and even depend on the life stage of an organism. What is limiting for one species might be abundant for another, and what is limiting today might be plentiful tomorrow.

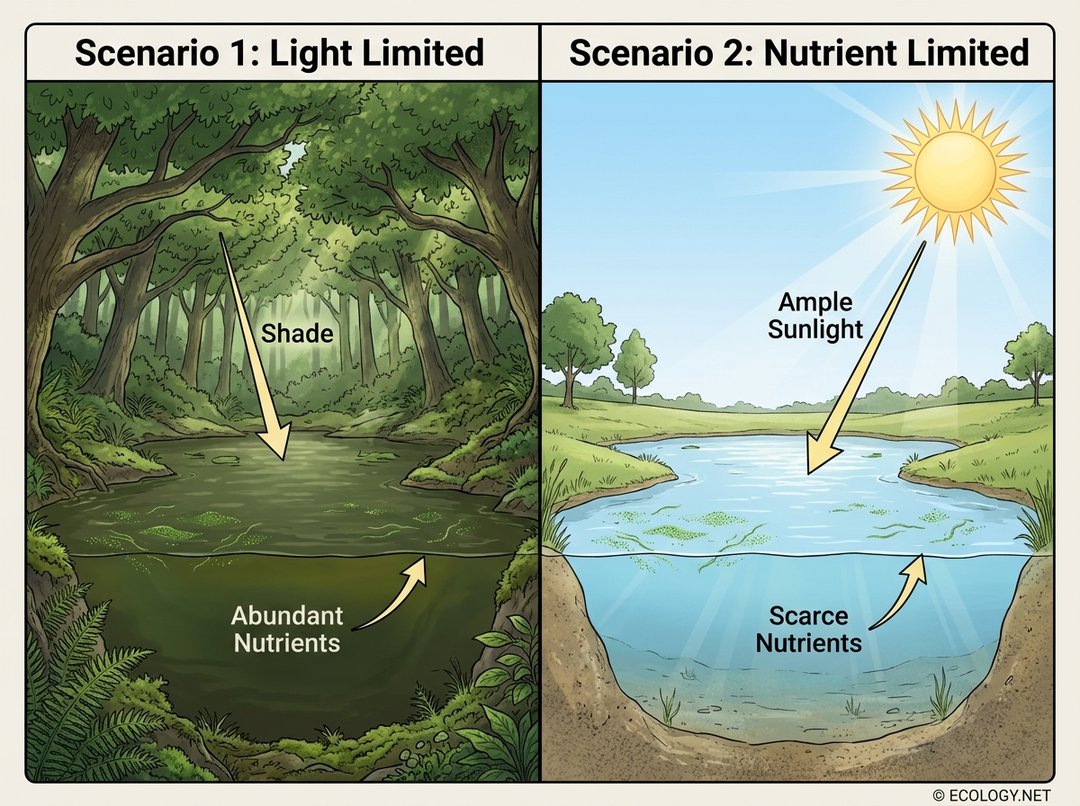

Consider a pond ecosystem:

In one pond, dense overhanging trees might create heavy shade, making light the primary limiting factor for algal growth, even if nutrients are abundant. In another pond, exposed to full sunlight, a scarcity of essential nutrients like phosphorus might be the limiting factor, despite ample light. Both ponds might show sparse algal growth, but for entirely different reasons. This illustrates how the same environment can present different limiting factors under varying conditions.

Seasonal changes also play a significant role. In temperate forests, temperature and light are limiting in winter, while water might become limiting during a dry summer. For migratory birds, food availability along their migration route can be a critical limiting factor at certain times of the year.

Impacts Across the Ecological Spectrum

The concept of limiting factors has profound implications for understanding and managing the natural world.

Population Dynamics

Limiting factors are the primary drivers of population growth and decline. When resources are abundant, populations can grow exponentially. However, as a population increases, it eventually encounters a limiting factor, leading to a slowdown in growth and often stabilizing around the environment’s carrying capacity. The carrying capacity is the maximum population size of a biological species that can be sustained indefinitely by a given environment.

Species Distribution

The geographical range of a species is often defined by its tolerance to various limiting factors. Cacti are limited to arid regions by their need for low water, while specific fish species are limited to certain water temperatures or salinity levels. Understanding these limits is vital for predicting how species might respond to environmental changes.

Ecosystem Health and Management

Ecologists and conservationists use the concept of limiting factors to diagnose problems in ecosystems. If a fish population is declining, identifying the limiting factor—perhaps pollution affecting water quality, overfishing, or habitat loss—is the first step toward effective conservation. In agriculture, farmers optimize yields by identifying and addressing limiting factors like soil nutrients, water, or pest control.

Human Impact and Global Change

Human activities frequently alter limiting factors, often with unintended consequences. Deforestation can increase light availability in some areas but reduce water retention. Pollution can introduce new limiting factors (e.g., toxins) or exacerbate existing ones (e.g., nutrient runoff leading to algal blooms that then deplete oxygen, making oxygen a limiting factor for other aquatic life). Climate change is fundamentally shifting temperature and water regimes globally, altering limiting factors for countless species and ecosystems, leading to species range shifts and extinctions.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Perspectives

For those delving deeper into ecological science, the interplay of limiting factors presents complex and fascinating challenges.

Interaction of Limiting Factors

While Liebig’s Law highlights the single most limiting factor, in reality, factors often interact. For example, a plant might tolerate lower light levels if water is abundant, or vice versa. This concept, known as ecological compensation or resource trade-offs, means that organisms can sometimes compensate for a deficiency in one resource by having an abundance of another. However, there are limits to this compensation, and eventually, one factor will become critically limiting.

Thresholds and Tipping Points

Ecosystems often exhibit thresholds, points at which a small change in a limiting factor can trigger a large, often irreversible, shift in the system. For instance, a slight increase in nutrient runoff into a lake might push it past a threshold, leading to a massive algal bloom, oxygen depletion, and a complete restructuring of the aquatic community. Identifying these thresholds is critical for proactive environmental management.

Limiting Factors in Ecological Succession

As ecosystems undergo succession, the dominant limiting factors often change. In early successional stages, light and space might be limiting for pioneer species. As larger plants establish, they might create shade, making light limiting for understory species, while nutrients become more available through decomposition. Understanding these shifts helps explain how communities change over time.

Climate Change and Shifting Limitations

Global climate change is fundamentally altering the distribution and intensity of abiotic limiting factors worldwide. Rising temperatures are pushing species beyond their thermal tolerance limits, while altered precipitation patterns are changing water availability. For many species, the limiting factor that once defined their range is now shifting, forcing adaptation, migration, or extinction. This dynamic interplay makes predicting future ecological scenarios incredibly complex.

Conclusion: The Pervasive Influence

Limiting factors are not just abstract ecological concepts; they are the invisible architects of life on Earth. They dictate where species can live, how large populations can grow, and the overall health and resilience of ecosystems. From the microscopic world of soil bacteria to the vast expanses of the oceans, the principle remains constant: life’s potential is always constrained by its most scarce, essential resource.

By recognizing and understanding these ecological bottlenecks, we gain invaluable insights into the natural world. This knowledge empowers us to make more informed decisions in agriculture, conservation, and environmental policy, ensuring that we work with, rather than against, the fundamental laws that govern life on our planet.