Lakes: Earth’s Sparkling Jewels of Freshwater

Lakes, those captivating bodies of still water nestled within land, are far more than mere puddles. They are dynamic ecosystems, vital reservoirs, and breathtaking landscapes that have shaped civilizations and harbored incredible biodiversity for millennia. From the smallest alpine tarn to vast inland seas, lakes offer a window into geological history, ecological complexity, and the intricate dance of life. Understanding these aquatic wonders reveals much about our planet’s past, present, and future.

What is a Lake? Defining the Basics

At its core, a lake is a large body of relatively still water, completely enclosed by land. While this definition seems straightforward, the distinction between a lake and a pond can sometimes be blurry. Generally, lakes are larger and deeper than ponds, often exhibiting distinct thermal stratification and wave action. Unlike rivers, lake water flow is minimal, and unlike oceans, lakes are freshwater (though some can be saline) and are not directly connected to the global ocean system.

Key characteristics of lakes include:

- Basin: A depression in the Earth’s surface that holds the water.

- Water Source: Typically fed by rivers, streams, groundwater, and precipitation.

- Stillness: Water movement is primarily driven by wind, temperature, and density differences, rather than a strong directional current.

- Depth: Varies immensely, from a few meters to over a kilometer deep.

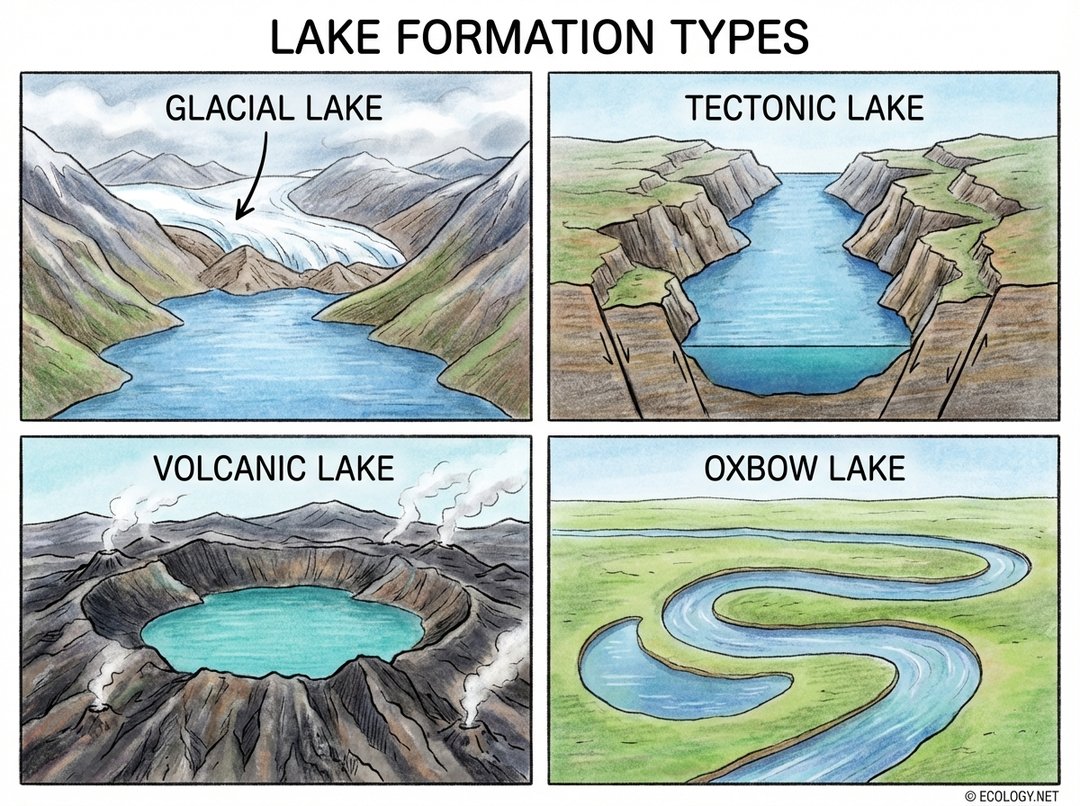

The Birth of a Lake: Diverse Formation Processes

The sheer variety of lakes across the globe is a testament to the powerful and diverse forces that sculpt our planet. Each lake tells a unique geological story, born from processes ranging from the slow grind of glaciers to the explosive power of volcanoes.

Let us explore some of the most common and fascinating ways lakes come into being:

Glacial Lakes

These are perhaps the most widespread type of natural lake in temperate and polar regions. Formed by the erosive and depositional power of glaciers, they include:

- Cirque Lakes (Tarns): Small, deep lakes found in bowl-shaped depressions carved by glaciers at mountain tops.

- Finger Lakes: Long, narrow lakes occupying U-shaped valleys scoured by continental glaciers, like those in New York State.

- Great Lakes: Massive freshwater bodies, such as the North American Great Lakes, formed in depressions deepened by vast ice sheets.

Tectonic Lakes

These lakes arise from movements of the Earth’s crust, often associated with fault lines and rift valleys. They are typically very deep and elongated.

- Rift Valley Lakes: Formed when tectonic plates pull apart, creating deep depressions that fill with water. Lake Baikal in Siberia, the deepest lake in the world, and many of the African Great Lakes like Lake Tanganyika are prime examples.

- Graben Lakes: Similar to rift valley lakes, but specifically formed in a down-dropped block of land between two parallel faults.

Volcanic Lakes

Volcanic activity can create lakes in several ways:

- Crater Lakes: Formed when the craters or calderas of dormant or extinct volcanoes fill with water. Crater Lake in Oregon, USA, is a stunning example.

- Lava Dam Lakes: Occur when lava flows block a river or stream, impounding water behind the natural dam.

Fluvial Lakes (Oxbow Lakes)

These lakes are a dynamic feature of river floodplains. As a meandering river flows across flat land, it erodes the outer banks and deposits sediment on the inner banks. Over time, a meander loop can become so exaggerated that the river cuts a new, straighter path during a flood, leaving the old loop isolated as a crescent-shaped oxbow lake. The Mississippi River floodplain is dotted with numerous oxbow lakes.

Other Lake Types

While the above are major categories, lakes can also form through:

- Karst Lakes: In limestone regions, dissolution of rock can create sinkholes that fill with water.

- Landslide Lakes: Formed when a landslide blocks a river valley.

- Artificial Lakes (Reservoirs): Created by human construction of dams for water supply, power generation, or flood control.

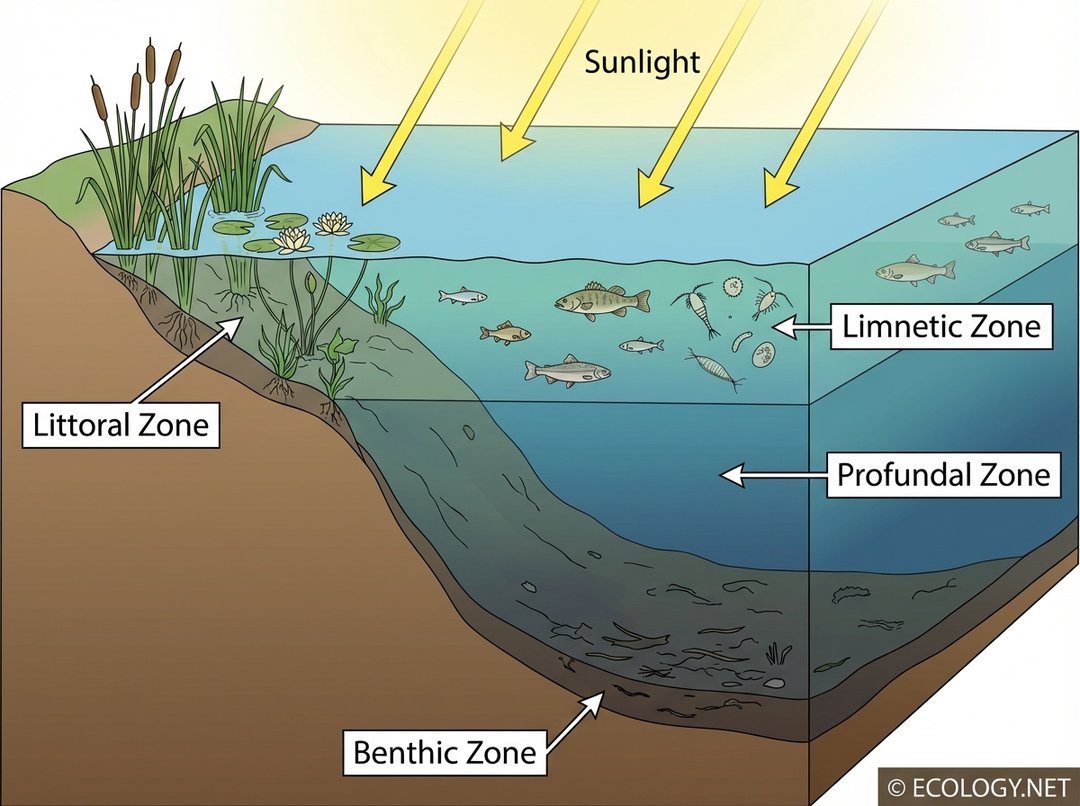

Anatomy of a Lake: A World Within

Beyond their formation, lakes possess a complex internal structure that dictates the distribution of life within them. A cross-section of a lake reveals distinct ecological zones, each with its own unique environmental conditions and inhabitants.

The Littoral Zone

This is the shallow, near-shore area where sunlight penetrates all the way to the bottom. It is often the most productive and biodiverse part of a lake.

- Characteristics: Abundant rooted aquatic plants (emergent, submerged, floating), warmer temperatures, rich in oxygen.

- Life: Home to a vast array of organisms including insects, snails, crustaceans, amphibians, small fish, and the larvae of many aquatic species.

The Limnetic Zone

Also known as the pelagic zone, this is the open, sunlit surface water away from the shore.

- Characteristics: Dominated by plankton, both phytoplankton (microscopic plants) and zooplankton (microscopic animals). Sunlight decreases with depth.

- Life: The primary producers here are phytoplankton, forming the base of the food web. Zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, and various fish species, such as perch and bass, feed on both plankton and smaller fish.

The Profundal Zone

This is the deep, dark water layer beneath the limnetic zone, where sunlight does not penetrate.

- Characteristics: Cold, low in oxygen, especially in stratified lakes, and receives organic matter that sinks from the upper zones.

- Life: Limited to organisms adapted to low light and low oxygen conditions, such as certain bacteria, fungi, and specialized invertebrates. Decomposition is a dominant process here.

The Benthic Zone

This refers to the bottom of the lake, encompassing the sediment and the organisms that live within or on it.

- Characteristics: Composed of mud, sand, or rock, rich in organic detritus. Oxygen levels can vary greatly depending on depth and lake productivity.

- Life: A diverse community of decomposers (bacteria, fungi), detritivores (worms, insect larvae), and bottom-dwelling fish (catfish, carp) thrive here, playing a crucial role in nutrient cycling.

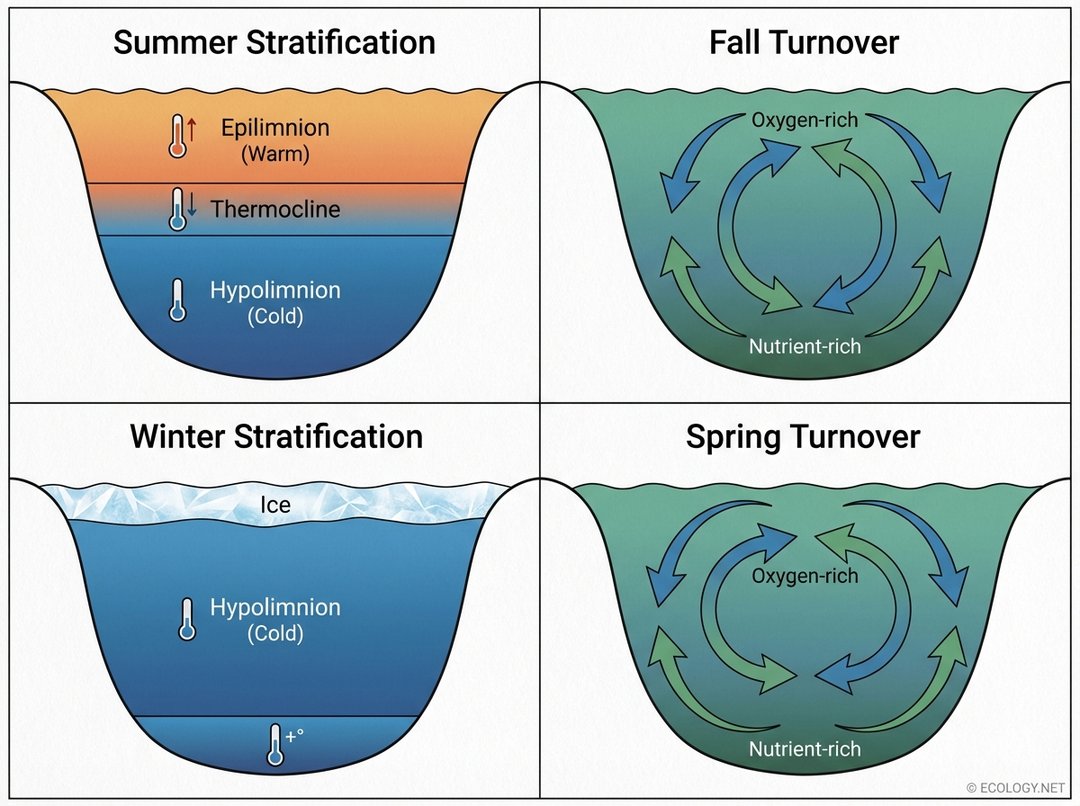

The Lake’s Rhythms: Seasonal Changes and Dynamics

Lakes in temperate regions are not static bodies of water; they undergo fascinating seasonal transformations driven by temperature changes. This phenomenon, known as thermal stratification and turnover, is critical for the distribution of oxygen and nutrients throughout the lake.

Summer Stratification

During summer, the sun warms the surface waters, creating distinct layers:

- Epilimnion: The warm, oxygen-rich upper layer, where most photosynthesis occurs.

- Thermocline: A middle layer characterized by a rapid decrease in temperature with increasing depth, acting as a barrier to mixing.

- Hypolimnion: The cold, dense bottom layer, often low in oxygen due to decomposition and isolation from the surface.

Fall Turnover

As autumn arrives, surface waters cool, becoming denser. When the epilimnion cools to a temperature similar to the hypolimnion, the thermocline weakens. Wind action can then easily mix the entire water column. This “turnover” brings oxygen-rich water to the bottom and nutrient-rich water from the bottom to the surface, revitalizing the lake.

Winter Stratification

In winter, if temperatures drop below freezing, an ice layer forms on the surface. Water is densest at 4 degrees Celsius, so the coldest water (just above freezing) remains at the surface under the ice, while slightly warmer, denser water (around 4 degrees Celsius) settles at the bottom. This creates an inverse stratification, providing a stable, insulated environment for aquatic life beneath the ice.

Spring Turnover

When spring arrives, the ice melts, and the surface water warms to 4 degrees Celsius. As this water warms, it becomes denser and sinks, leading to another period of full mixing, similar to fall turnover. This spring turnover once again redistributes oxygen and nutrients, preparing the lake for the growing season.

Life in the Lake: Ecosystems and Biodiversity

Lakes are bustling hubs of life, supporting intricate food webs that range from microscopic organisms to large predators. The specific species found in a lake depend on its size, depth, nutrient levels, and geographical location.

Producers, Consumers, Decomposers

The foundation of any lake ecosystem is its primary producers:

- Phytoplankton: Microscopic algae floating in the limnetic zone.

- Macrophytes: Larger aquatic plants rooted in the littoral zone.

These producers are consumed by primary consumers, such as zooplankton, snails, and insect larvae. Secondary consumers, like small fish and amphibians, feed on these primary consumers. Apex predators, including larger fish (e.g., pike, trout), birds (e.g., herons, eagles), and mammals (e.g., otters), sit at the top of the food chain. Decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi, break down dead organic matter throughout all zones, recycling vital nutrients back into the ecosystem.

Key Organisms

Lakes are home to an astonishing array of life:

- Invertebrates: Dragonflies, mayflies, caddisflies, freshwater mussels, crayfish.

- Fish: Diverse species adapted to different zones, from sunfish in the littoral to lake trout in deep, cold waters.

- Amphibians and Reptiles: Frogs, salamanders, turtles, snakes.

- Birds: Ducks, geese, loons, kingfishers, ospreys.

- Mammals: Beavers, muskrats, otters.

Types of Lakes: Beyond Formation

Lakes can also be classified based on their nutrient status and productivity, which profoundly influences the types of life they can support.

Oligotrophic Lakes

- Characteristics: Deep, clear, cold, nutrient-poor, with high oxygen levels throughout the water column.

- Life: Support limited plant growth but often host cold-water fish species like trout and salmon, which require high oxygen.

Mesotrophic Lakes

- Characteristics: Intermediate in terms of depth, clarity, and nutrient levels, representing a transitional stage between oligotrophic and eutrophic.

- Life: Support a moderate diversity of aquatic plants and fish.

Eutrophic Lakes

- Characteristics: Shallow, warm, nutrient-rich, often murky due to high algal growth, and can experience low oxygen levels (hypoxia or anoxia) in the hypolimnion.

- Life: Abundant plant and algal growth, supporting warm-water fish like carp and catfish, but susceptible to algal blooms and fish kills.

Dystrophic Lakes

- Characteristics: Characterized by high levels of humic substances (organic acids from decaying vegetation), making the water brown or tea-colored. They are often acidic and low in nutrients.

- Life: Support specialized communities adapted to acidic, low-nutrient conditions.

Saline Lakes

While most lakes are freshwater, some are saline, meaning they have high concentrations of dissolved salts. These typically occur in arid regions where evaporation exceeds inflow, leading to salt accumulation. Examples include the Great Salt Lake in Utah and the Dead Sea. Life in these lakes is highly specialized, often dominated by brine shrimp and salt-tolerant microbes.

The Importance of Lakes: Why They Matter

Lakes are indispensable to both natural ecosystems and human societies. Their ecological, economic, and cultural value is immense.

- Freshwater Supply: Lakes are a primary source of drinking water for millions of people worldwide.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: They provide critical habitats for a vast array of aquatic and terrestrial species, many of which are unique to lake environments.

- Climate Regulation: Large lakes can influence local weather patterns, moderating temperatures and contributing to regional humidity.

- Recreation and Tourism: Lakes offer countless opportunities for swimming, boating, fishing, and wildlife viewing, supporting local economies.

- Economic Value: Beyond tourism, lakes support fisheries, provide water for agriculture and industry, and can be used for hydroelectric power generation.

- Cultural Significance: Many lakes hold deep cultural and spiritual importance for indigenous communities and are central to local folklore and history.

Threats to Lakes and Conservation

Despite their resilience, lakes face numerous threats from human activities and global environmental changes. Protecting these vital ecosystems requires concerted conservation efforts.

Major Threats

- Pollution:

- Nutrient Pollution (Eutrophication): Excess nitrogen and phosphorus from agriculture, sewage, and urban runoff can lead to harmful algal blooms, oxygen depletion, and loss of biodiversity.

- Chemical Pollution: Industrial waste, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals can contaminate lake waters, harming aquatic life and human health.

- Plastic Pollution: Microplastics and larger plastic debris accumulate in lakes, posing risks to wildlife.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures can lead to warmer lake waters, altered stratification patterns, increased evaporation, and changes in ice cover, impacting lake ecosystems.

- Invasive Species: Non-native species introduced accidentally or intentionally can outcompete native species, disrupt food webs, and alter habitat structure.

- Over-extraction: Excessive withdrawal of water for human use can lower lake levels, reduce habitat, and increase salinity.

- Habitat Degradation: Shoreline development, wetland destruction, and sedimentation can degrade critical lake habitats.

Conservation Efforts

Protecting lakes involves a multi-faceted approach:

- Watershed Management: Managing land use within the entire watershed to reduce pollution runoff.

- Pollution Control: Implementing stricter regulations on industrial and agricultural discharges, improving wastewater treatment.

- Restoration Projects: Undertaking efforts to restore degraded lake habitats, such as removing invasive species or re-establishing native vegetation.

- Sustainable Water Use: Promoting efficient water use and responsible water withdrawal practices.

- Public Awareness and Education: Engaging communities in lake stewardship and promoting responsible recreational practices.

Conclusion

Lakes are truly extraordinary features of our planet, each a unique world shaped by geological forces and teeming with life. From their diverse origins to their intricate internal structures and seasonal rhythms, lakes offer endless opportunities for scientific discovery and aesthetic appreciation. They are not merely bodies of water, but dynamic ecosystems that provide invaluable services to both nature and humanity. By understanding the complexities of lakes and recognizing the threats they face, we can all contribute to their preservation, ensuring these sparkling jewels continue to enrich our world for generations to come.