The natural world is a tapestry of constant motion, a dynamic stage where life continually seeks new opportunities and adapts to changing circumstances. Among the most fundamental processes driving this dynamism is immigration, a concept often discussed in human terms but equally vital and fascinating in the realm of ecology. Understanding ecological immigration is key to grasping how populations persist, expand, and interact within their environments.

What is Ecological Immigration? Defining the Movement

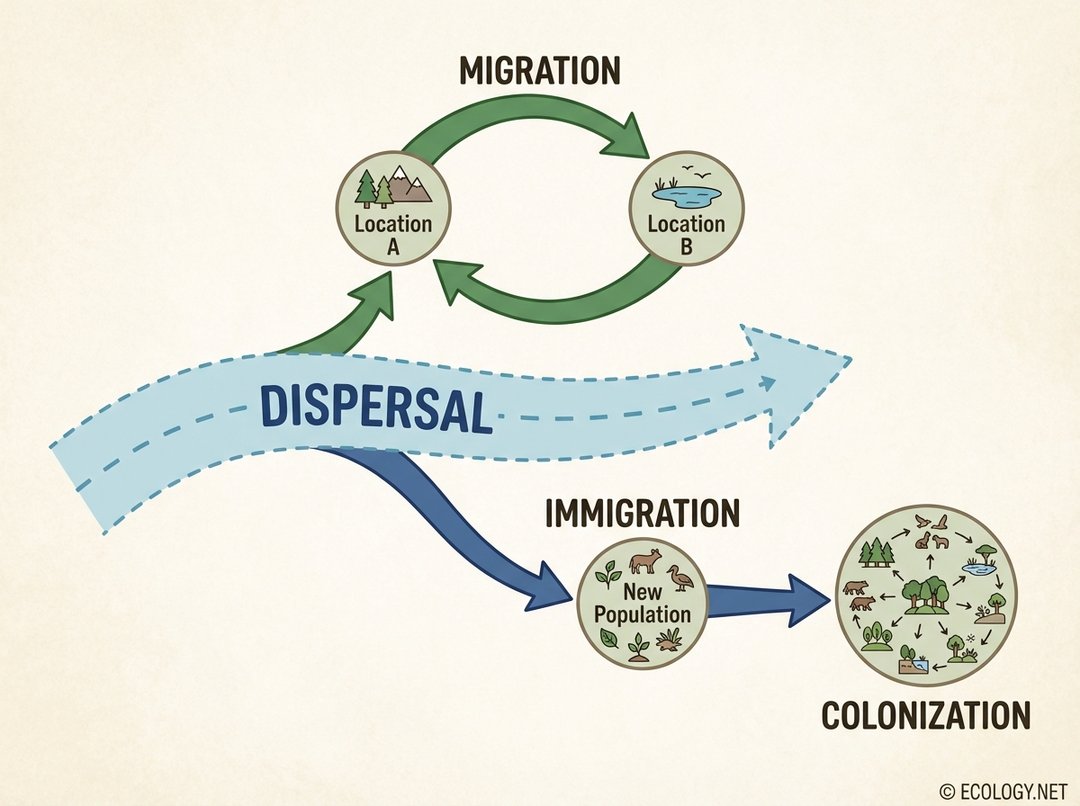

At its core, ecological immigration refers to the movement of individuals into a new population or area. It is a specific type of movement that contributes to the growth and genetic diversity of a recipient population. To fully appreciate immigration, it is helpful to distinguish it from related terms that describe the broader spectrum of organismal movement.

- Dispersal: This is the most general term, referring to any movement of individuals away from their birth site or from their current population. It is a one-way trip and can be short or long distance. Think of dandelion seeds carried by the wind, spreading randomly across a field.

- Migration: Unlike dispersal, migration is typically a cyclical, seasonal, or periodic movement between two distinct locations. Many bird species, for example, migrate thousands of miles between breeding grounds and wintering grounds, returning to the same areas year after year.

- Immigration: This is the arrival of individuals into a new population or area. When a new bird joins an existing flock in a different territory, it is immigrating. This influx can bring new genes and increase the population size.

- Emigration: The opposite of immigration, this is the departure of individuals from a population or area.

- Colonization: This occurs when immigrants successfully establish a new, self-sustaining population in a previously unoccupied or sparsely populated area. It is the successful outcome of immigration leading to establishment.

Immigration is not merely a curiosity; it is a powerful force that can reshape ecosystems. It can introduce new genetic material, bolster declining populations, or even lead to the establishment of entirely new species in a region.

The Drivers of Immigration: Why Do Species Move?

Species do not immigrate without reason. Their movements are often driven by a complex interplay of “push” and “pull” factors, compelling them to leave one area and seek another.

Push Factors: What Makes Them Leave?

- Resource Scarcity: A lack of food, water, or suitable nesting sites can force individuals to seek new territories. For instance, a severe drought might push deer herds to move to areas with more abundant forage.

- Overpopulation: When a population grows too large for its current habitat, competition for resources intensifies, pushing some individuals to disperse and potentially immigrate elsewhere.

- Predation Pressure: High numbers of predators can make an area unsafe, prompting prey species to move to safer havens.

- Habitat Degradation: Pollution, deforestation, or other forms of habitat destruction can render an area uninhabitable, forcing species to relocate.

Pull Factors: What Attracts Them?

- Resource Availability: The promise of abundant food, water, and shelter is a strong magnet. A newly opened forest patch with ample berries might attract a population of bears.

- Favorable Climate: Species may move to areas with more suitable temperatures, rainfall, or humidity, especially in the face of climate change.

- Reduced Competition: An area with fewer competitors for resources can be highly attractive, offering a better chance of survival and reproduction.

- Absence of Predators: A new territory free from major predators can offer a significant survival advantage.

- Breeding Opportunities: The availability of suitable mates and safe breeding grounds can be a powerful draw for individuals seeking to reproduce.

Navigating the Landscape: Barriers and Corridors

The journey of an immigrant species is rarely straightforward. The landscape itself presents a myriad of challenges and opportunities, shaping where and how species can move.

Barriers to Movement

Barriers are features that impede or prevent the movement of organisms. They can isolate populations, reduce genetic exchange, and even lead to local extinctions.

- Geographical Barriers:

- Mountains: Tall mountain ranges can be insurmountable for many species, especially those adapted to specific altitudes or climates.

- Large Water Bodies: Oceans, vast lakes, and wide rivers can prevent terrestrial species from crossing, while landmasses act as barriers for aquatic species.

- Deserts: Arid environments can be too harsh for species not adapted to extreme heat and lack of water.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Human activities often break up continuous habitats into smaller, isolated patches. Roads, urban development, and agricultural fields can create barriers that prevent species from moving between suitable areas. A forest-dwelling squirrel, for example, might be unwilling or unable to cross a busy highway to reach another patch of trees.

- Human-Made Structures: Fences, dams, and even large buildings can act as significant obstacles for many animals.

Ecological Corridors: Pathways for Life

Conversely, ecological corridors are pathways that facilitate movement between habitats. They are crucial for maintaining connectivity and allowing immigration to occur.

- River Systems: Rivers often act as natural highways, allowing both aquatic and riparian species to move across landscapes. Fish can travel upstream and downstream, and animals like otters or beavers can follow riverbanks.

- Mountain Passes: Gaps or lower elevations in mountain ranges can provide crucial routes for species to cross otherwise impassable terrain.

- Forest Strips: Narrow bands of forest connecting larger forest patches allow arboreal and understory species to move safely.

- Island Stepping Stones: A series of small islands can act as intermediate stops, allowing species to cross larger bodies of water incrementally, colonizing one island before moving to the next.

- Wildlife Crossings: Human-engineered solutions like overpasses or underpasses built over or under roads are increasingly used to mitigate the barrier effect of infrastructure, allowing animals to safely cross.

The Impact of Immigration: A Double-Edged Sword

Immigration has profound consequences, both positive and negative, for the immigrant species, the recipient population, and the entire ecosystem.

Benefits of Immigration

- Increased Genetic Diversity: New arrivals bring fresh genetic material, which can reduce inbreeding and increase a population’s ability to adapt to environmental changes, such as new diseases or shifts in climate.

- Population Boost: For small or declining populations, immigration can provide a much-needed influx of individuals, preventing local extinction and aiding recovery.

- Species Range Expansion: Successful immigration and colonization allow species to expand their geographical range, occupying new territories.

- Ecosystem Resilience: A diverse array of species, often facilitated by immigration, can make an ecosystem more robust and better able to withstand disturbances.

Challenges and Risks of Immigration

- Increased Competition: New arrivals can compete with existing residents for limited resources like food, water, and shelter, potentially leading to declines in native populations.

- Disease Transmission: Immigrants can introduce new pathogens or parasites to a naive population, leading to widespread disease and mortality.

- Hybridization: Closely related immigrant species might interbreed with native species, potentially diluting the genetic distinctiveness of the native population.

- Invasive Species: When an immigrant species establishes itself in a new environment and outcompetes native species, causing ecological or economic harm, it becomes an invasive species. Examples include the zebra mussel in North American waterways or the cane toad in Australia.

Advanced Concepts: Metapopulations and Source-Sink Dynamics

For a deeper understanding of how immigration shapes population persistence, ecologists often look at concepts like metapopulations and source-sink dynamics. These frameworks help explain the interconnectedness of spatially separated populations.

Metapopulations: A Network of Patches

A metapopulation is a group of spatially separated populations of the same species that interact through immigration and emigration. Imagine a landscape dotted with several patches of suitable habitat, each supporting a small population of a particular species. These populations are not entirely isolated; individuals occasionally move between them. This movement, often immigration, is crucial for the long-term survival of the entire metapopulation.

- If one small population experiences a local extinction due to a sudden environmental change or disease, it can be recolonized by immigrants from a healthy neighboring population.

- This dynamic balance of local extinctions and recolonizations, facilitated by immigration, allows the species to persist across the broader landscape even if individual patches are unstable.

Source-Sink Dynamics: Givers and Takers

Within a metapopulation, not all patches are equal. This leads to the concept of source-sink dynamics:

- Source Populations: These are thriving, high-quality habitats where birth rates exceed death rates. They produce a surplus of individuals who then emigrate to other areas. Source populations are the “givers” in the network, constantly supplying new individuals. For example, a large, protected forest might be a source for a particular bird species.

- Sink Populations: These are lower-quality habitats where death rates exceed birth rates. Without continuous immigration from source populations, sink populations would decline and eventually go extinct. They are the “takers,” relying on external input to persist. A small, fragmented forest patch near a city might be a sink, only maintaining its bird population because of immigrants from a larger, healthier forest.

Understanding source-sink dynamics is vital for conservation. Protecting source populations is paramount, as their health underpins the survival of many sink populations that might otherwise disappear.

Immigration in a Changing World: Conservation Insights

In an era of rapid environmental change, understanding and managing ecological immigration has become more critical than ever. Human activities are altering landscapes at an unprecedented pace, creating new barriers and disrupting ancient corridors.

Conservation Strategies

- Protecting and Restoring Corridors: Establishing and maintaining ecological corridors, such as wildlife bridges, riparian zones, or protected land strips, is essential to allow species to move between fragmented habitats.

- Identifying and Protecting Source Populations: Conservation efforts often focus on identifying and safeguarding key source populations, recognizing their role in sustaining broader metapopulations.

- Mitigating Barriers: Reducing the impact of human-made barriers, for example, by designing roads with wildlife crossings or removing obsolete dams, can significantly improve connectivity.

- Managing Invasive Species: Understanding the pathways of immigration for potentially invasive species is crucial for prevention and control, protecting native ecosystems from harm.

- Considering Climate Change: As climates shift, species will need to move to new areas to find suitable conditions. Facilitating this climate-driven immigration through connected landscapes is a growing conservation challenge.

The movement of life across landscapes is not just a biological phenomenon; it is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of nature. Immigration, in all its forms, reminds us that ecosystems are not static, isolated entities, but rather dynamic, interconnected webs of life.

Conclusion: The Ever-Moving Tapestry of Life

Ecological immigration is a fundamental process that shapes the distribution, genetics, and persistence of species across the globe. From the smallest insect seeking a new plant to the largest mammal traversing continents, the drive to move and establish in new territories is a powerful force. It enriches genetic diversity, allows populations to recover from setbacks, and enables species to adapt to an ever-changing world.

By understanding the intricate dance of push and pull factors, the challenges of barriers, and the opportunities presented by corridors, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complex dynamics of life on Earth. As stewards of this planet, recognizing the importance of immigration allows us to make informed decisions that support biodiversity and ensure the continued vibrancy of our natural world.