Life on Earth is an intricate dance of energy transfer, and at the very foundation of many ecosystems stand the unsung heroes of the plant world: the grazers. These remarkable creatures, often overlooked in their daily munching, are far more than just hungry mouths. They are vital architects of landscapes, engineers of nutrient cycles, and essential players in the grand drama of ecological balance. Understanding grazers reveals a fascinating world of adaptation, interaction, and profound environmental impact.

What Exactly Are Grazers? Defining the Dietary Difference

At its core, a grazer is an herbivore that primarily feeds on low-lying vegetation, such as grasses, herbs, and other ground-level plants. This dietary preference distinguishes them from their close relatives, the browsers, who typically consume leaves, twigs, and fruits from shrubs and trees. While some animals may exhibit a mixed diet, the classification often hinges on their predominant feeding strategy.

Consider the classic image of a cow peacefully munching in a pasture. This is the quintessential grazer, perfectly adapted to harvest vast quantities of fibrous, nutrient-dense grasses. Their wide mouths, specialized teeth, and complex digestive systems are all geared towards processing this specific type of forage.

The Diverse World of Grazers: More Than Just Cows

While cattle, sheep, and horses are prominent examples, the world of grazers extends far beyond domesticated livestock. This feeding strategy has evolved independently in countless lineages across the globe, leading to an astonishing array of forms and sizes.

- Mammalian Grazers:

- Large Herbivores: African buffalo, wildebeest, zebras, kangaroos, and various deer species (when feeding on grass) are iconic grazers of savannas and grasslands.

- Smaller Mammals: Rabbits, hares, guinea pigs, and many rodent species also fit the grazer description, nibbling on ground vegetation.

- Avian Grazers:

- Waterfowl: Geese, ducks, and swans often graze on aquatic vegetation and grasses near water bodies.

- Terrestrial Birds: Some species of grouse and other ground-dwelling birds consume significant amounts of grass and herbaceous plants.

- Reptilian Grazers:

- Tortoises: Giant tortoises, for instance, are primarily grazers, slowly consuming vast amounts of ground vegetation.

- Iguanas: Marine iguanas of the Galápagos are unique grazers, feeding on algae from underwater rocks.

- Invertebrate Grazers:

- Insects: Grasshoppers, caterpillars, and many beetle larvae are voracious grazers, consuming leaves and stems of low-lying plants.

- Gastropods: Snails and slugs graze on algae, fungi, and tender plant shoots.

- Marine Invertebrates: Sea urchins and some species of crabs graze on algae in marine environments, playing a crucial role in coral reef health.

This incredible diversity highlights the evolutionary success of the grazing lifestyle, adapting to nearly every terrestrial and even some aquatic environments where low-lying vegetation is abundant.

The Ecological Architects: Why Grazers Matter So Much

Grazers are not merely consumers; they are active shapers of their environments, performing critical ecological functions that ripple through entire ecosystems.

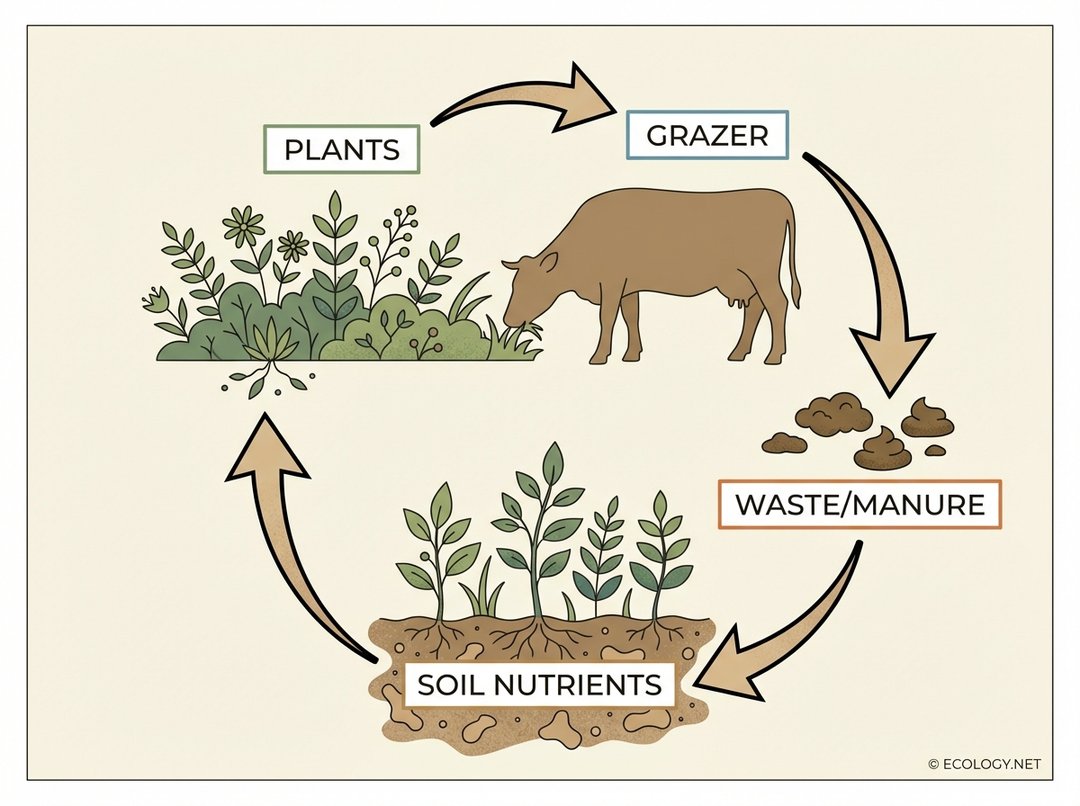

Nutrient Cycling: The Great Recyclers

One of the most fundamental roles of grazers is their contribution to nutrient cycling. By consuming plant matter, they convert organic material into forms that can be more readily returned to the soil. Their waste products, rich in nitrogen and other essential nutrients, fertilize the ground, promoting new plant growth. This continuous cycle is vital for maintaining soil fertility and ecosystem productivity.

Habitat Modification and Maintenance

Grazers act as natural lawnmowers, preventing the dominance of a few fast-growing plant species and maintaining open grasslands. This selective feeding creates a mosaic of habitats, benefiting a wider array of plant and animal species. For example, in African savannas, wildebeest grazing prevents the encroachment of woody plants, preserving the open plains that many other species rely on.

Seed Dispersal

Many plant seeds pass unharmed through the digestive tracts of grazers. As the animals move across the landscape, they effectively disperse these seeds, aiding in plant colonization and genetic exchange across different areas. This is particularly important for plants that lack other efficient dispersal mechanisms.

Impact on Plant Diversity

While it might seem counterintuitive, grazing can actually enhance plant diversity. By consuming dominant species, grazers create opportunities for less competitive plants to thrive. This “intermediate disturbance” can prevent monocultures and foster a richer botanical community. However, overgrazing, where too many animals consume too much vegetation, can lead to the opposite effect, degrading habitats and reducing biodiversity.

Prey for Predators

Grazers form the base of many food webs, providing a crucial food source for a wide range of predators. From lions hunting zebras on the savanna to birds of prey targeting rabbits in temperate grasslands, the abundance of grazers directly supports populations of carnivores, maintaining a healthy predator-prey balance.

Adaptations for a Grazing Lifestyle: Built for the Bite

The success of grazers is a testament to their remarkable evolutionary adaptations, allowing them to thrive on a diet that is often tough, fibrous, and low in readily available nutrients.

Dental Specializations

Grazers possess highly specialized teeth. Their incisors are often broad and flat, perfect for clipping grass close to the ground. The molars are typically large, ridged, and continuously growing, designed for grinding tough plant material. The jaw structure allows for a wide, side-to-side grinding motion, maximizing the efficiency of food processing.

Digestive Systems: The Fermentation Factories

Processing cellulose, the primary component of plant cell walls, is a formidable digestive challenge. Grazers have evolved two main strategies to overcome this:

- Ruminants: Animals like cows, sheep, and deer have a multi-chambered stomach (rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum). The rumen acts as a fermentation vat, where symbiotic microbes break down cellulose. This process, known as rumination, involves regurgitating and re-chewing cud, further breaking down the plant material for more efficient digestion.

- Hindgut Fermenters: Animals such as horses, rhinos, and rabbits have a single stomach but rely on a greatly enlarged cecum or colon for microbial fermentation. While generally less efficient than rumination, this system allows for faster passage of food, enabling these animals to consume larger quantities of forage.

Locomotion and Defense

Given their position as primary consumers, grazers are often prey animals. Many have evolved adaptations for swift escape, such as long legs and powerful muscles for running. Herd behavior is also a common defense strategy, offering safety in numbers and collective vigilance against predators.

Grazers in Different Ecosystems

The role and impact of grazers vary significantly across different biomes, reflecting the unique plant communities and environmental conditions.

- Grasslands and Savannas: These ecosystems are defined by their dominant grass cover and are home to the most iconic large grazers. The intricate relationship between grazers, fire, and rainfall shapes these vast landscapes.

- Tundras: In the harsh Arctic and alpine tundras, grazers like reindeer, caribou, and musk oxen feed on tough grasses, sedges, and lichens, playing a role in nutrient cycling in these cold, slow-growing environments.

- Aquatic Environments: Manatees graze on seagrass beds, while various fish species and invertebrates graze on algae, demonstrating that grazing is not exclusive to terrestrial habitats.

- Deserts: Even in arid regions, specialized grazers like some species of desert rodents and insects manage to find and consume sparse grasses and herbaceous plants, adapting to extreme water scarcity.

Human Connection: Grazers and Us

The relationship between humans and grazers is ancient and profound. Domesticated grazers like cattle, sheep, and goats have been central to human civilization for millennia, providing food, fiber, and labor. Their management forms the backbone of pastoral and agricultural economies worldwide.

However, human activities also present significant challenges to wild grazer populations and the ecosystems they inhabit. Habitat loss, fragmentation, and climate change threaten many species. Overgrazing by livestock can lead to soil erosion, desertification, and a decline in biodiversity, particularly in fragile environments.

Conservation efforts increasingly recognize the importance of maintaining healthy grazer populations and managing grazing pressure. Rewilding initiatives, which reintroduce large grazers to landscapes, aim to restore natural ecological processes and enhance ecosystem resilience. Understanding the delicate balance of grazing is crucial for sustainable land management and biodiversity conservation.

Conclusion

Grazers, from the smallest insect to the largest mammal, are indispensable components of Earth’s ecosystems. Their seemingly simple act of consuming plants drives complex ecological processes, from nutrient cycling and habitat creation to supporting entire food webs. They are living examples of evolutionary ingenuity, perfectly adapted to transform vast quantities of vegetation into life-sustaining energy.

By appreciating the profound ecological roles of grazers, we gain a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of nature. Their continued health and presence are not just about preserving individual species, but about safeguarding the vitality and resilience of the planet’s most fundamental ecological systems.