Gardening: Cultivating Life, Understanding Ecology

Gardening is often seen as a simple hobby, a pleasant way to connect with nature and grow food or flowers. Yet, beneath the surface of every tilled bed and thriving plant lies a profound interaction with complex ecological principles. Far from merely planting seeds, gardeners are active participants in shaping ecosystems, influencing biodiversity, and managing natural processes. To truly master the art of gardening is to understand the ecological dance that unfolds in our backyards, transforming us from simple cultivators into stewards of miniature ecosystems.

Succession and the Gardener’s Role: A Constant Dialogue with Nature

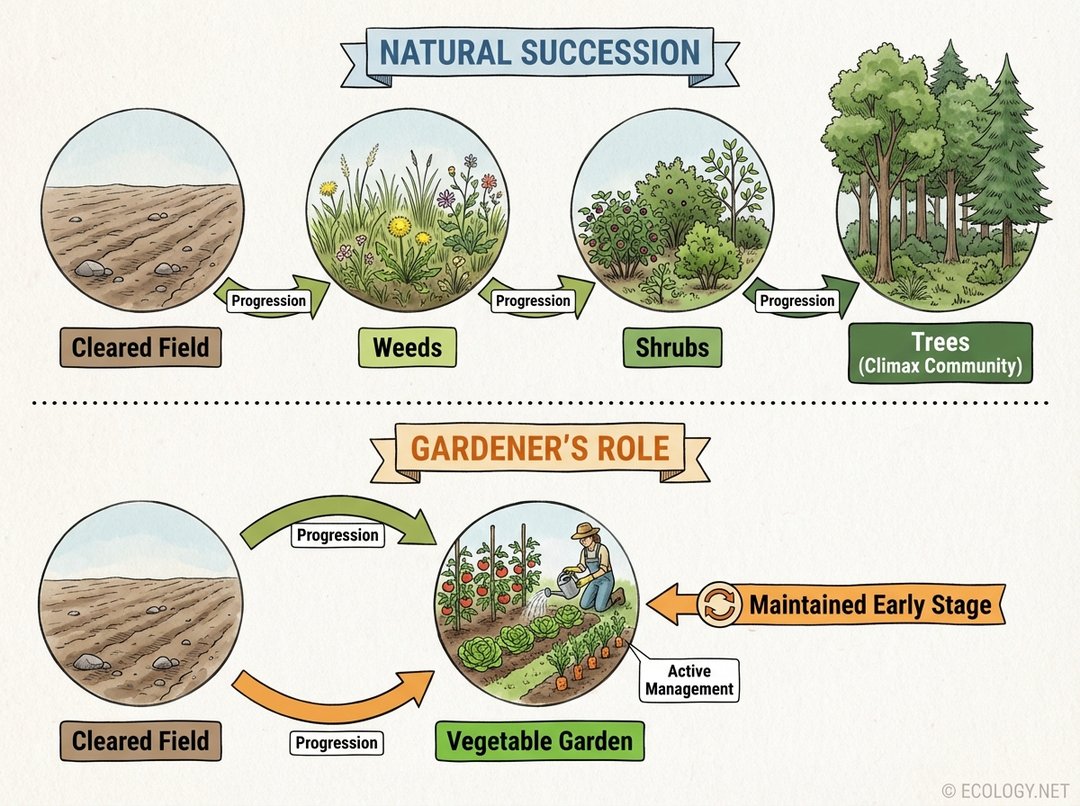

One of the most fundamental ecological concepts at play in any garden is ecological succession. This is the natural process by which ecosystems change over time, often beginning with bare ground and progressing through various stages of plant and animal communities until a stable, climax community is reached. Think of an abandoned field: it quickly fills with weeds, then shrubs, and eventually, if left undisturbed, small trees will emerge, leading to a forest.

This image illustrates the fundamental ecological concept of succession and how gardening actively interrupts and manages this process to maintain desired plant communities. A gardener, in essence, constantly works against the natural progression of succession. When a gardener clears a plot for a vegetable garden, they are resetting the ecological clock to an early successional stage. The act of weeding, pruning, and harvesting is a continuous effort to prevent the ecosystem from advancing to its natural climax. Instead of allowing a field to become a forest, the gardener maintains it as a productive, early-stage community, rich in annual vegetables or desired ornamentals. This constant intervention highlights the gardener’s active role in directing ecological outcomes.

Soil: The Foundation of Life and a Thriving Ecosystem

While plants are the visible stars of any garden, the true magic happens beneath our feet, in the soil. Soil is not merely dirt; it is a dynamic, living ecosystem, teeming with an incredible diversity of organisms that are essential for plant health and overall garden vitality. Understanding soil is paramount to successful ecological gardening.

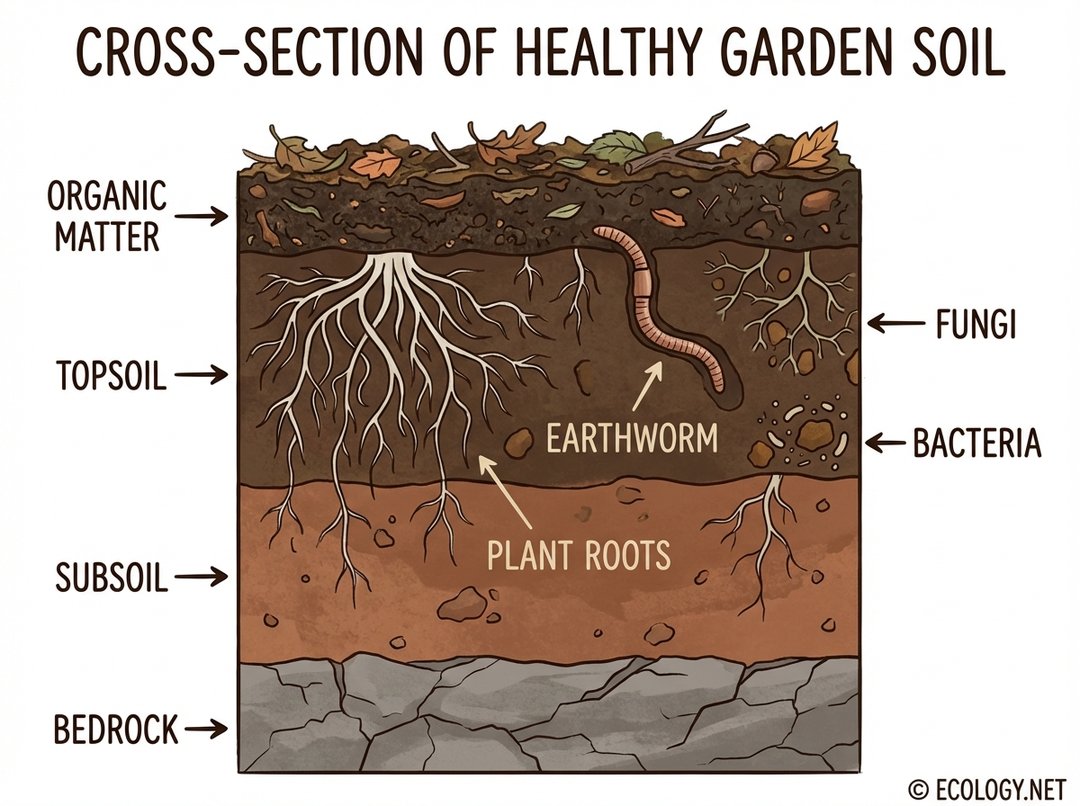

This image visually explains the critical components and structure of healthy soil, emphasizing its role as a complex ecosystem teeming with life. A healthy soil profile typically consists of several layers. At the very top is the organic matter layer, composed of decaying leaves, compost, and other plant residues. This layer is crucial for nutrient cycling, water retention, and providing food for soil organisms. Below this lies the topsoil, the most fertile layer, rich in humus and teeming with life. Here, plant roots anchor themselves, and a vast network of microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, work tirelessly to break down organic matter and make nutrients available to plants. Earthworms burrow through these layers, aerating the soil and improving drainage. Further down are the subsoil and finally bedrock, which provide structural support and mineral reserves.

The Unseen Workforce: Soil Microorganisms

The health of your garden is directly tied to the health of its microbial inhabitants.

- Bacteria: Billions of bacteria in a handful of soil perform vital functions, from nitrogen fixation (converting atmospheric nitrogen into a form plants can use) to decomposing organic matter.

- Fungi: Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, extending the root system’s reach and enhancing nutrient and water uptake. Other fungi are crucial decomposers.

- Earthworms and Insects: These larger organisms aerate the soil, improve drainage, and mix organic matter throughout the profile, creating channels for roots and water.

By adding compost, avoiding synthetic chemicals, and minimizing soil disturbance, gardeners can foster a robust and resilient soil ecosystem, ensuring a steady supply of nutrients for their plants.

Niche Partitioning and Polyculture: Mimicking Nature’s Design

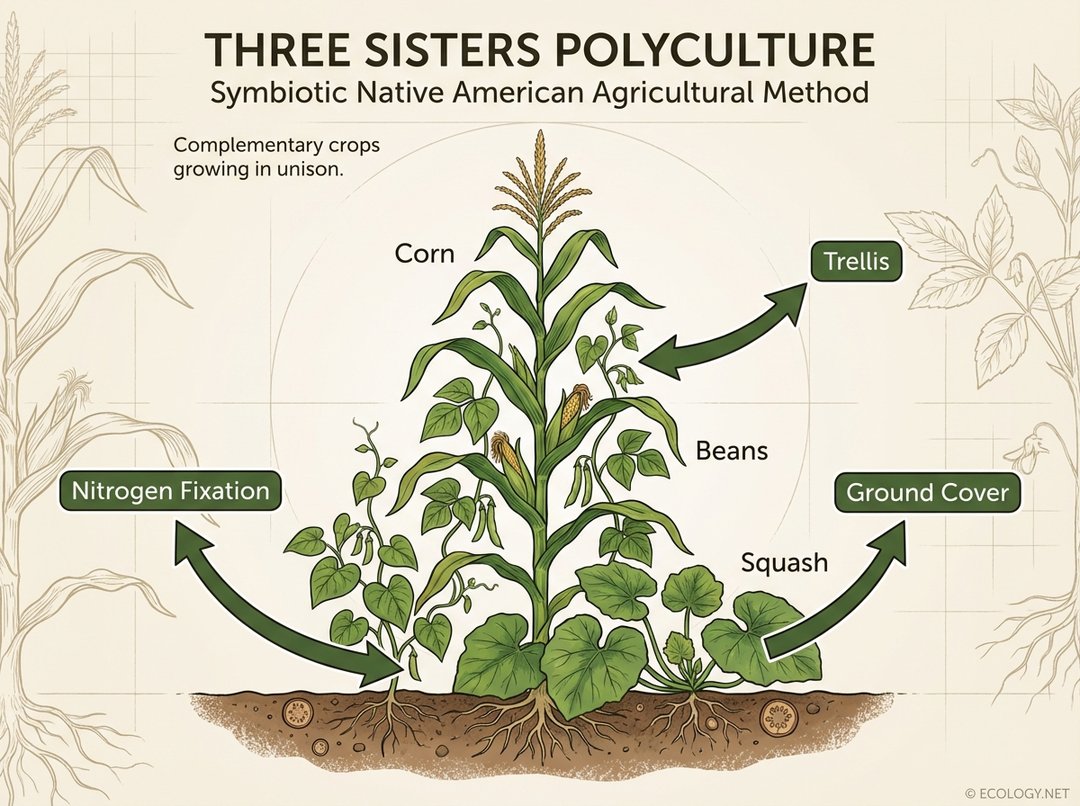

Traditional gardening often favors monoculture, growing large plots of a single crop. While efficient for large-scale agriculture, monoculture can be ecologically fragile, susceptible to widespread pest outbreaks and nutrient depletion. Ecological gardening, however, embraces the concept of polyculture, growing multiple species together, much like natural ecosystems. This approach leverages principles like niche partitioning, where different species utilize resources in different ways or at different times, minimizing competition and maximizing overall productivity.

This image visually demonstrates the advanced ecological concept of niche partitioning and polyculture using the classic ‘Three Sisters’ example, illustrating how different plants can benefit each other when grown together. The “Three Sisters” method, practiced by indigenous peoples for centuries, is a prime example of polyculture in action.

- Corn: The tall corn stalks provide a natural trellis for the climbing beans, allowing them to reach sunlight without needing artificial support.

- Beans: Legumes like beans are nitrogen fixers. They host bacteria in their root nodules that convert atmospheric nitrogen into a usable form for plants, enriching the soil for the corn and squash.

- Squash: The broad leaves of squash plants spread across the ground, acting as a living mulch. This suppresses weeds, conserves soil moisture, and helps regulate soil temperature.

Together, these three plants create a mutually beneficial micro-ecosystem, each filling a unique niche and contributing to the health and productivity of the whole. This is a powerful demonstration of how biodiversity can enhance resilience and yield in a garden.

Beyond the Three Sisters: Other Polyculture Examples

Many other companion planting strategies utilize polyculture principles:

- Planting marigolds or nasturtiums near vegetables to deter pests.

- Growing herbs like basil near tomatoes to improve flavor and repel insects.

- Interplanting different types of greens, root vegetables, and herbs to create a diverse canopy and root system.

These methods reduce the need for synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, fostering a more balanced and sustainable garden environment.

The Gardener’s Impact: Stewarding a Sustainable Future

Ecological gardening is more than just a set of techniques; it is a philosophy that recognizes the interconnectedness of all living things. By understanding and working with natural processes rather than against them, gardeners can create spaces that are not only productive but also resilient, beautiful, and beneficial to the wider environment.

Embracing practices such as composting, rainwater harvesting, choosing native plants, and supporting local biodiversity transforms a garden into a vibrant ecological hub. It reduces our environmental footprint, supports pollinators and beneficial insects, and contributes to a healthier planet. Every choice made in the garden, from the seeds sown to the soil amended, has an ecological ripple effect. By becoming conscious ecological gardeners, we cultivate not just plants, but a deeper connection to the living world around us, fostering a sustainable future one garden bed at a time.