Forests are far more than just collections of trees. They are intricate, dynamic ecosystems that cover vast stretches of our planet, playing an indispensable role in sustaining life and shaping the very air we breathe. From the towering redwoods of North America to the dense jungles of the Amazon, these green giants represent some of Earth’s most biodiverse and vital habitats.

Understanding forests means appreciating their complexity, their global distribution, and the myriad ways they interact with the environment and human societies. They are living laboratories, carbon powerhouses, and havens for countless species, all while offering profound benefits to humanity.

What is a Forest? A Living Tapestry

At its core, a forest is an area of land dominated by trees. However, this simple definition barely scratches the surface of what a forest truly is. A forest is a complex ecological system characterized by a high density of trees, which in turn create a unique microclimate and habitat for a vast array of other organisms, including shrubs, herbs, fungi, insects, and animals.

These ecosystems are defined not just by their woody vegetation but by the intricate web of interactions that occur within them. Trees provide structure, shade, and food, influencing everything from soil composition to the flow of water. The sheer scale and interconnectedness of these elements make forests incredibly resilient and productive systems.

The Vertical World: Layers of a Forest

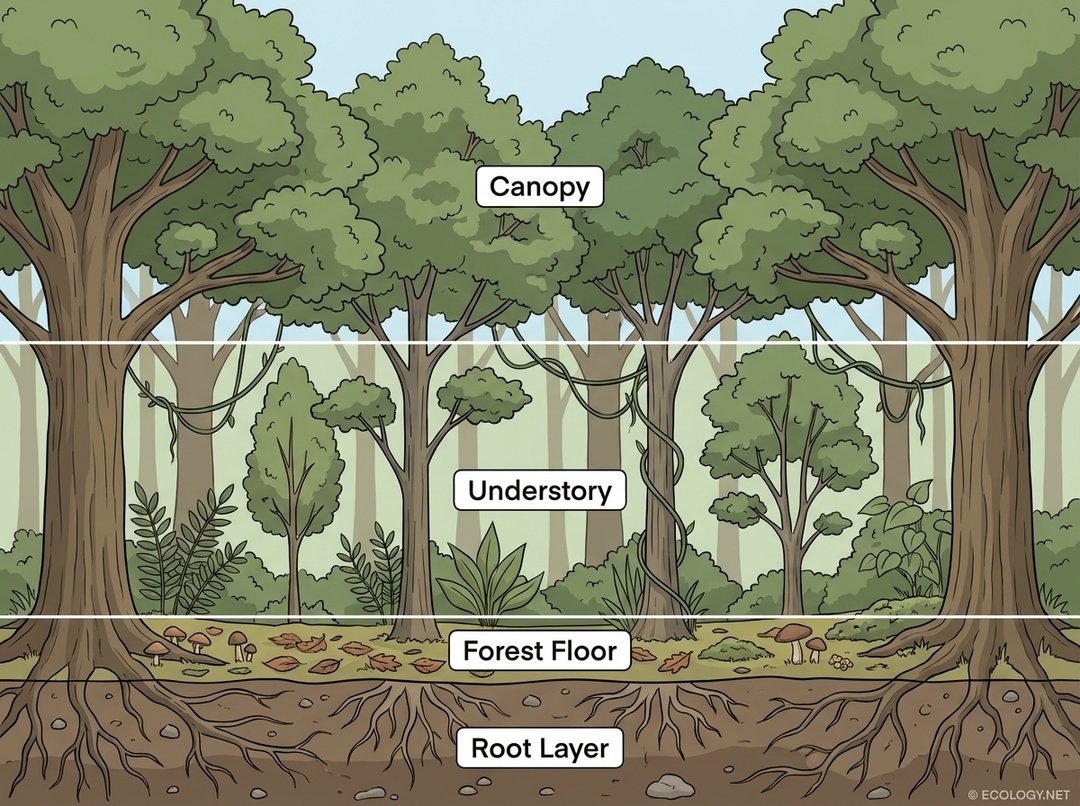

One of the most fascinating aspects of a forest is its vertical structure, often described as distinct layers or strata. Each layer offers unique conditions and supports different forms of life, creating a multi-dimensional habitat. This stratification allows for a greater diversity of species to coexist by partitioning resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients.

- Canopy Layer: This is the uppermost layer, formed by the crowns of the tallest trees. It acts as the primary interface with sunlight, capturing most of the solar energy. The canopy is a bustling hub of activity, home to many birds, insects, and arboreal mammals. It also significantly influences the microclimate below, reducing wind speed and moderating temperature.

- Understory Layer: Situated beneath the canopy, the understory consists of smaller trees, saplings, shrubs, and woody vines that are adapted to lower light levels. Plants in this layer often have larger leaves to maximize light absorption. Many young trees wait for an opening in the canopy to grow taller.

- Forest Floor Layer: This is the ground level, covered by leaf litter, fallen branches, mosses, ferns, and fungi. It is a critical zone for decomposition, where decomposers like bacteria, fungi, and invertebrates break down organic matter, returning nutrients to the soil. Small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians often make their home here.

- Root Layer: Extending beneath the surface, the root layer is a hidden world of tree roots, fungal networks (mycorrhizae), and soil organisms. Roots anchor the trees, absorb water and nutrients, and interact with the complex soil food web. This layer is crucial for the stability and health of the entire forest ecosystem.

Understanding these layers helps us appreciate the intricate architecture of a forest and how different organisms find their niche within this complex environment.

A Global Mosaic: Types of Forests Across the World

Forests are not uniform. Their characteristics vary dramatically depending on climate, geography, and soil conditions, leading to a stunning diversity of forest types across the globe. Each type is a unique adaptation to its specific environmental challenges.

Major Forest Types

- Tropical Rainforests: Found near the equator, these are Earth’s most biodiverse terrestrial ecosystems. Characterized by high rainfall, warm temperatures year-round, and incredibly dense, multi-layered vegetation. Trees are typically evergreen, and the forest floor receives very little light. Examples include the Amazon Rainforest and the Congo Basin.

- Temperate Deciduous Forests: Located in mid-latitude regions, these forests experience distinct seasons. Trees like oak, maple, and beech shed their leaves in autumn, conserving water and energy during colder months. They are known for their vibrant fall foliage and rich, fertile soils. Found in eastern North America, Europe, and parts of Asia.

- Boreal Forests (Taiga): The largest terrestrial biome, stretching across northern latitudes in North America, Europe, and Asia. Dominated by coniferous trees such as spruce, fir, and pine, which are adapted to long, cold winters and short, cool summers. Their needle-like leaves and conical shape help shed snow.

- Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands, and Scrub: Found in regions with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, such as the Mediterranean Basin, California, Chile, and parts of Australia. Vegetation here is typically evergreen, with drought-adapted trees and shrubs like olive trees, cork oaks, and various chaparral species.

- Temperate Coniferous Forests: These forests are found in temperate regions with moderate rainfall and cooler temperatures. They are dominated by coniferous trees like pines, spruces, and firs. Examples include the vast pine forests of the southeastern United States or the coastal redwood forests of California.

- Montane Forests: Found on mountain slopes, these forests vary with altitude. As elevation increases, temperatures drop, and precipitation patterns change, leading to distinct vegetation zones, from broadleaf trees at lower elevations to conifers and eventually alpine meadows higher up.

This global tapestry of forest types highlights the incredible adaptability of life and the powerful influence of climate on ecosystems.

The Unsung Heroes: Ecological Roles of Forests

The ecological services provided by forests are immense and often taken for granted. They are fundamental to the health of the planet and the well-being of all living things.

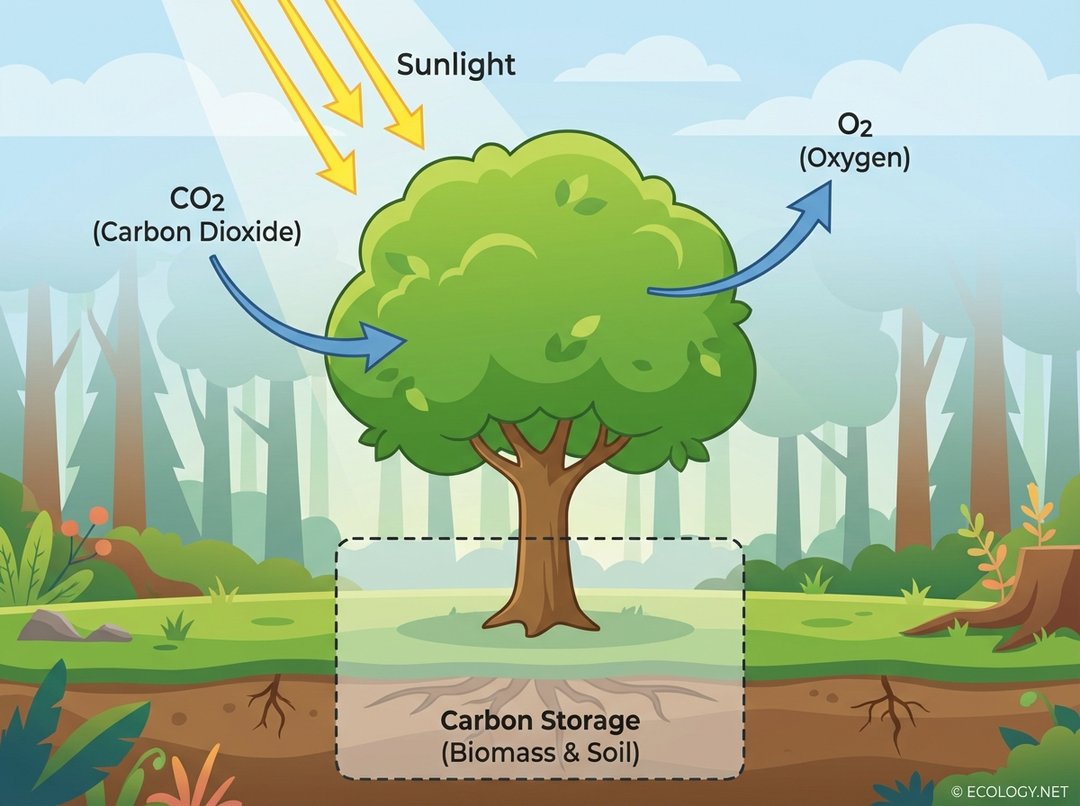

Carbon Sinks and Oxygen Producers

Perhaps one of the most critical roles of forests is their involvement in the global carbon cycle. Through photosynthesis, trees absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, converting it into organic matter for growth. This process effectively sequesters carbon, storing it in their biomass (trunks, branches, leaves, roots) and in the soil. Simultaneously, they release oxygen (O2) as a byproduct, replenishing the air we breathe.

A mature forest can store hundreds of tons of carbon per hectare, making them vital allies in mitigating climate change by reducing atmospheric CO2 levels.

Biodiversity Hotspots

Forests are unparalleled reservoirs of biodiversity. They provide habitat for an estimated 80% of terrestrial species, including countless plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. The complex structure of forests, with their multiple layers and diverse microclimates, creates a multitude of niches for different species to thrive. For example, a single hectare of tropical rainforest can host hundreds of tree species, each supporting its own community of insects and epiphytes.

Water Cycle Regulation

Forests play a crucial role in regulating the water cycle. Their canopies intercept rainfall, reducing erosion and allowing water to slowly infiltrate the soil. Tree roots help absorb and store water, releasing it gradually into streams and rivers, which helps maintain consistent water flow and prevents flooding. Through transpiration, trees release water vapor into the atmosphere, contributing to cloud formation and regional rainfall patterns. The Amazon rainforest, for instance, generates much of its own rainfall through this process.

Soil Health and Erosion Prevention

The dense network of tree roots binds soil particles together, preventing erosion by wind and water. The constant input of organic matter from fallen leaves and decaying wood enriches the soil, creating a fertile substrate that supports a wide range of microbial life. Healthy forest soils are vital for nutrient cycling and overall ecosystem productivity.

Climate Regulation

Beyond carbon sequestration, forests influence local and global climates in other ways. Their shade cools the ground, and the process of transpiration has a cooling effect on the surrounding air. Large forest areas can create their own weather patterns, influencing temperature and humidity over vast regions.

Beyond Ecology: Forests and Humanity

The value of forests extends far beyond their ecological functions. They provide numerous direct and indirect benefits to human societies.

- Economic Resources: Forests are a source of timber for construction and paper, as well as non-timber forest products such as fruits, nuts, medicinal plants, resins, and rubber. Sustainable forestry practices aim to harvest these resources without compromising the long-term health of the forest.

- Cultural and Spiritual Significance: For many indigenous cultures and communities worldwide, forests hold deep spiritual and cultural meaning. They are sacred spaces, sources of traditional medicines, and integral to their way of life.

- Recreation and Well-being: Forests offer invaluable opportunities for recreation, including hiking, camping, birdwatching, and simply enjoying nature. Spending time in forests has been shown to reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance physical health, a concept sometimes referred to as “forest bathing.”

Threats and Conservation: Protecting Our Green Lungs

Despite their immense value, forests globally face significant threats, primarily driven by human activities.

Major Threats

- Deforestation: The clearing of forests for other land uses, such as agriculture (cattle ranching, soy plantations), logging for timber, mining, and urban expansion, is the most pressing threat. This leads to habitat loss, biodiversity decline, and significant carbon emissions.

- Climate Change: Rising global temperatures, altered rainfall patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events like droughts and wildfires pose serious risks to forest health. Pests and diseases can also spread more easily in stressed forests.

- Illegal Logging: Unregulated and illegal harvesting of timber depletes forest resources, often without regard for sustainable practices or ecological impact.

Conservation Efforts

Protecting and restoring forests is a global imperative. Conservation strategies include:

- Sustainable Forest Management: Practices that ensure forests are managed to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This includes selective logging, reforestation, and protecting biodiversity.

- Protected Areas: Establishing national parks, wildlife reserves, and other protected areas to safeguard critical forest ecosystems from exploitation.

- Reforestation and Afforestation: Planting new trees in deforested areas (reforestation) or on land that has not historically been forested (afforestation) helps restore ecological functions and sequester carbon.

- Community Involvement: Engaging local communities and indigenous peoples in forest management and conservation efforts is crucial, as their traditional knowledge and stewardship are invaluable.

Conclusion

Forests are truly the Earth’s green lungs, intricate ecosystems that provide a breathtaking array of ecological services and vital resources. From regulating our climate and producing the oxygen we breathe to harboring immense biodiversity and offering spiritual solace, their importance cannot be overstated. As global citizens, understanding the profound value of forests and supporting their conservation is not merely an environmental concern, but a fundamental commitment to the health and future of our planet.