The Dynamic Edges of Life: Unveiling the Secrets of Ecotones

Imagine walking through a dense forest, the air cool and damp, the ground covered in fallen leaves. Suddenly, the trees thin, the light brightens, and you step into an open, sun-drenched meadow teeming with wildflowers and buzzing insects. That fascinating transition zone, where one distinct ecosystem gracefully gives way to another, is what ecologists call an ecotone. Far from being a mere boundary, ecotones are vibrant, dynamic arenas of ecological interaction, often boasting a unique richness of life that makes them crucial for understanding biodiversity and conservation.

What Exactly is an Ecotone?

At its core, an ecotone is a transitional area between two different biological communities or ecosystems. Think of it as nature’s seam, where the characteristics of one habitat blend with those of another. These zones can be narrow or broad, natural or human-made, but they always represent a gradient of environmental conditions and species composition.

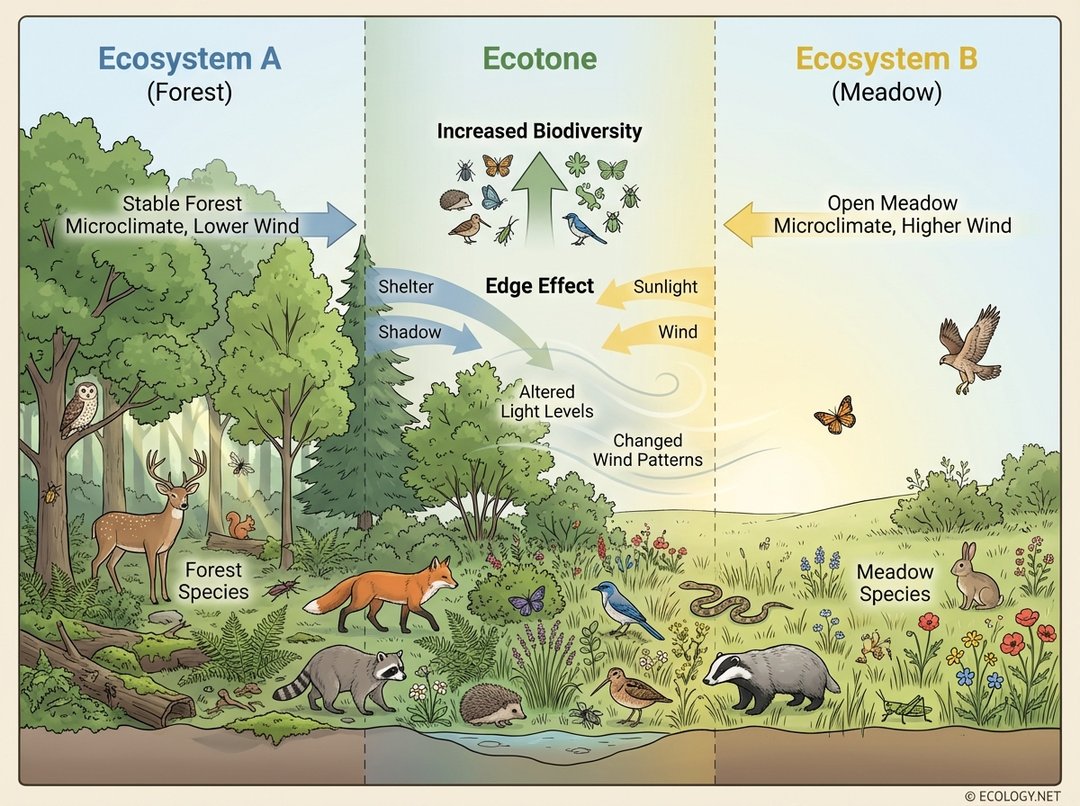

The image above visually explains the fundamental concept of an ecotone as a transitional zone between two distinct ecosystems, highlighting key characteristics like increased biodiversity and the edge effect. Within this transitional space, you often find a mix of species from both adjoining communities, alongside unique species specifically adapted to the conditions of the ecotone itself. This blending creates a distinctive ecological signature.

Why Are Ecotones So Special? The Edge Effect and Biodiversity Hotspots

Ecotones are not just lines on a map; they are often bustling centers of ecological activity. One of their most defining features is the “edge effect.” This phenomenon describes the tendency for ecotones to have a greater diversity and density of species than either of the adjacent communities. Several factors contribute to this ecological richness:

- Resource Overlap: Ecotones provide access to resources from both neighboring ecosystems. For instance, an animal might forage in the meadow for sunlight-loving plants and then retreat to the forest edge for shelter and shade.

- Unique Conditions: The environmental conditions within an ecotone are often distinct from the adjacent habitats. Factors like light intensity, wind exposure, temperature, and soil moisture can create a microclimate that supports specialized species.

- Increased Habitat Complexity: The structural diversity found in ecotones, such as varying vegetation heights or different substrate types, offers a wider array of niches for different organisms.

- Species from Both Sides: Ecotones act as meeting points, allowing species from both adjoining ecosystems to coexist, at least partially, within the transitional zone. This overlap naturally boosts species counts.

This combination of factors makes ecotones natural biodiversity hotspots, critical areas for maintaining ecological balance and supporting a wide array of life forms.

Examples of Ecotones in Action

Ecotones are ubiquitous, found across all biomes and at various scales. Recognizing them helps us appreciate the intricate connections within nature.

Forest-Grassland Ecotones

Perhaps one of the most classic examples, these zones occur where forests gradually give way to open grasslands or savannas. Here, you might find scattered trees, shrubs, and a mix of forest understory plants alongside grassland species. Animals like deer often thrive in these areas, utilizing both the cover of the forest and the foraging opportunities of the open land.

Riverbanks and Riparian Zones

The strips of land bordering rivers, streams, and lakes are prime examples of ecotones. These riparian zones transition from aquatic environments to terrestrial ones. They are characterized by unique plant communities adapted to fluctuating water levels and nutrient-rich soils. They also serve as vital corridors for wildlife movement and provide critical habitat for fish, amphibians, and birds.

Coastal Ecotones: Salt Marshes and Mangroves

Coastal areas offer some of the most dynamic and biologically rich ecotones.

The image above provides a concrete, photo-realistic example of an ecotone, specifically a salt marsh. It helps readers visualize how different ecosystems, such as a freshwater river and the salty ocean, converge to create a unique and biologically rich transitional zone. Salt marshes, for instance, are found where freshwater rivers meet the ocean, creating a gradient of salinity. Specialized grasses and other plants thrive here, providing crucial nursery grounds for fish and shellfish, and feeding grounds for migratory birds. Similarly, mangrove forests, found in tropical and subtropical coastal regions, form ecotones between land and sea, protecting coastlines and supporting immense biodiversity.

Mountain Treelines

As you ascend a mountain, you eventually reach a point where forests give way to alpine meadows or tundra. This treeline is a distinct ecotone, where environmental conditions like temperature, wind, and soil depth become too harsh for large trees to grow, leading to a transition to smaller, hardier vegetation.

Urban-Wildland Interfaces

Even in human-modified landscapes, ecotones exist. The boundary where urban development meets natural areas, such as a city park bordering a forest preserve, can function as an ecotone. These areas can present unique challenges and opportunities for both human and wildlife populations.

The Dynamics of Ecotones: Not Just Static Lines

Ecotones are not static features of the landscape. They are constantly shifting and evolving in response to various environmental factors. Climate change, for example, can cause treelines to move up mountainsides or coastal ecotones to migrate inland as sea levels rise. Natural disturbances like fires, floods, or insect outbreaks can also dramatically alter the position and characteristics of an ecotone. Human activities, including land use changes, pollution, and habitat fragmentation, exert significant pressure on these sensitive zones, often leading to their degradation or disappearance. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for effective ecological management.

Ecotones and Landscape Ecology

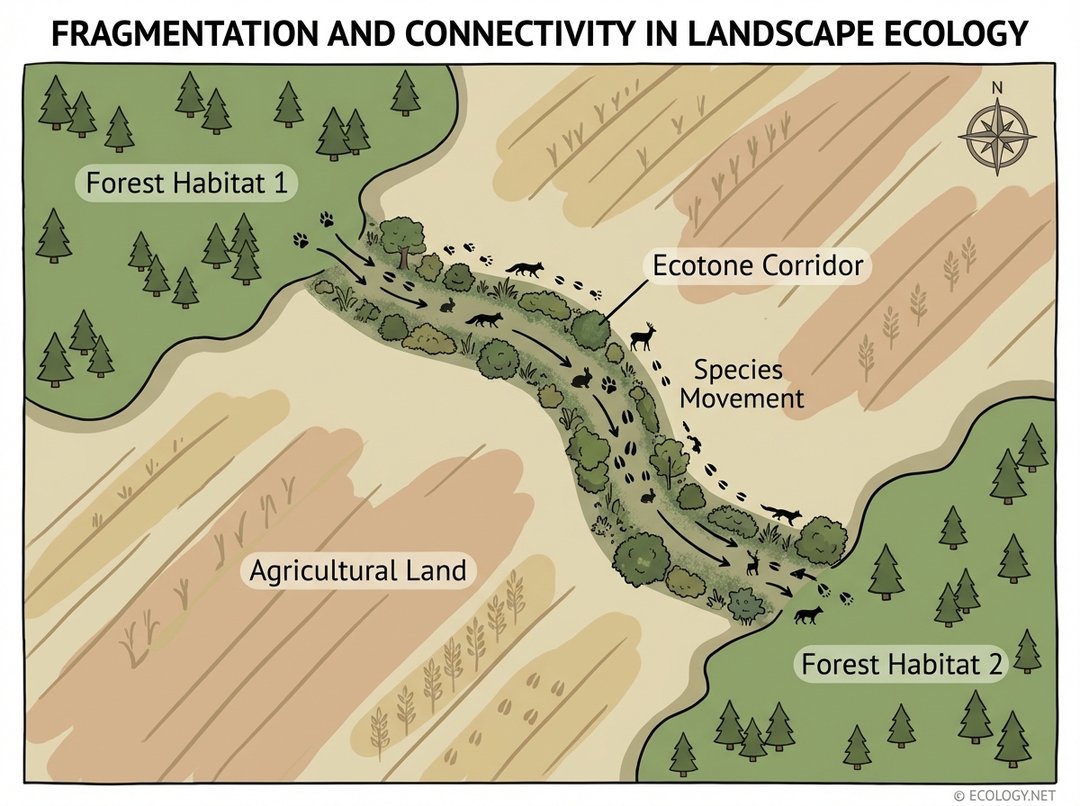

On a broader scale, ecotones play a pivotal role in landscape ecology, the study of how spatial patterns influence ecological processes. They are not just boundaries but often serve as vital connectors within a fragmented landscape.

Ecological Corridors

In landscapes where natural habitats are broken up by human development, ecotones can function as ecological corridors. These linear strips of transitional habitat allow species to move between isolated patches of suitable habitat, facilitating gene flow and reducing the risk of local extinctions.

The diagram above illustrates the critical role of ecotones in landscape ecology and conservation, specifically their function as corridors for species movement and gene flow between fragmented habitats. Without these corridors, populations can become isolated, leading to reduced genetic diversity and increased vulnerability to environmental changes.

Habitat Fragmentation

Conversely, the creation of abrupt, artificial edges through habitat fragmentation can sometimes create ecotones that are less beneficial. For example, a sharp boundary between a forest and a newly cleared agricultural field might expose forest interior species to increased predation or altered microclimates, leading to negative “edge effects” for those particular species. The quality and permeability of an ecotone are therefore critical considerations.

Conservation and Management of Ecotones

Given their ecological significance, the conservation and effective management of ecotones are paramount. Protecting these transitional zones means safeguarding biodiversity, maintaining ecosystem services, and enhancing the resilience of landscapes.

Key management strategies often include:

- Buffer Zone Creation: Establishing buffer zones around sensitive habitats can create more gradual ecotones, reducing harsh edge effects and providing additional protection.

- Corridor Restoration: Restoring or creating ecological corridors, often utilizing ecotonal habitats, can reconnect fragmented landscapes and facilitate species movement.

- Sustainable Land Use: Promoting land use practices that minimize abrupt transitions and allow for natural gradients can help maintain healthy ecotones.

- Monitoring and Research: Continuously studying ecotones helps scientists understand their dynamics and how best to manage them in the face of environmental change.

Conclusion

Ecotones are far more than simple dividing lines; they are dynamic, biologically rich interfaces where life thrives in unique ways. From the subtle blending of a forest into a meadow to the dramatic meeting of land and sea in a salt marsh, these transitional zones offer invaluable insights into ecological processes, biodiversity, and the interconnectedness of our natural world. Understanding and protecting ecotones is not just an academic exercise; it is a fundamental step towards preserving the intricate tapestry of life on Earth and ensuring the health and resilience of our planet’s ecosystems. The next time you encounter a boundary in nature, pause to appreciate the vibrant, often hidden, world of the ecotone.