Unveiling the Ecological Niche: More Than Just a Home

In the intricate tapestry of life, every organism plays a unique role, much like a specialized profession within a bustling city. This role, combined with its specific requirements and interactions, is what ecologists refer to as an “ecological niche.” Far more than just a physical address, a niche encompasses everything an organism needs to survive, thrive, and reproduce in its environment. Understanding this fundamental concept is key to unraveling the complexities of biodiversity, species coexistence, and the delicate balance of ecosystems.

Habitat Versus Niche: A Crucial Distinction

To truly grasp the concept of a niche, it is essential to first differentiate it from a habitat. While often used interchangeably in casual conversation, these terms hold distinct meanings in ecology.

- Habitat: Think of a habitat as an organism’s “address” or “home.” It is the physical place or type of environment where a species lives. For instance, a forest is a habitat, as is a coral reef, a desert, or a freshwater lake. It describes the physical surroundings.

- Niche: In contrast, a niche is an organism’s “profession” or “way of life” within that habitat. It describes how the organism interacts with its environment, what resources it uses, how it obtains food, how it reproduces, and how it interacts with other species. It is the sum of all biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) factors that define its existence.

Consider a forest. While the entire forest serves as a habitat for countless species, each species within it occupies a unique niche. A woodpecker, for example, drills into tree trunks for insects, while a squirrel forages for nuts on the forest floor. Both share the same habitat, but their roles, resource utilization, and interactions are distinct.

The Multifaceted Components of a Niche

An ecological niche is not a simple concept but a complex interplay of various factors. It is shaped by:

- Resource Utilization: This includes the type of food an organism eats, how it obtains water, the light levels it requires, and even the specific minerals it needs.

- Interactions with Other Species: A niche defines an organism’s relationships within the food web. Is it a predator, prey, parasite, or host? Does it compete with other species for resources? Does it form symbiotic relationships?

- Abiotic Factors: Non-living environmental conditions are critical. These include temperature ranges, humidity, soil pH, salinity, sunlight exposure, and water currents that an organism can tolerate and thrive in.

- Reproductive Strategies: The timing of reproduction, the number of offspring, parental care, and nesting sites are all integral parts of a species’ niche.

- Spatial Requirements: The specific areas an organism uses for foraging, breeding, resting, and escaping predators contribute to its niche.

Fundamental Versus Realized Niche: Potential Versus Reality

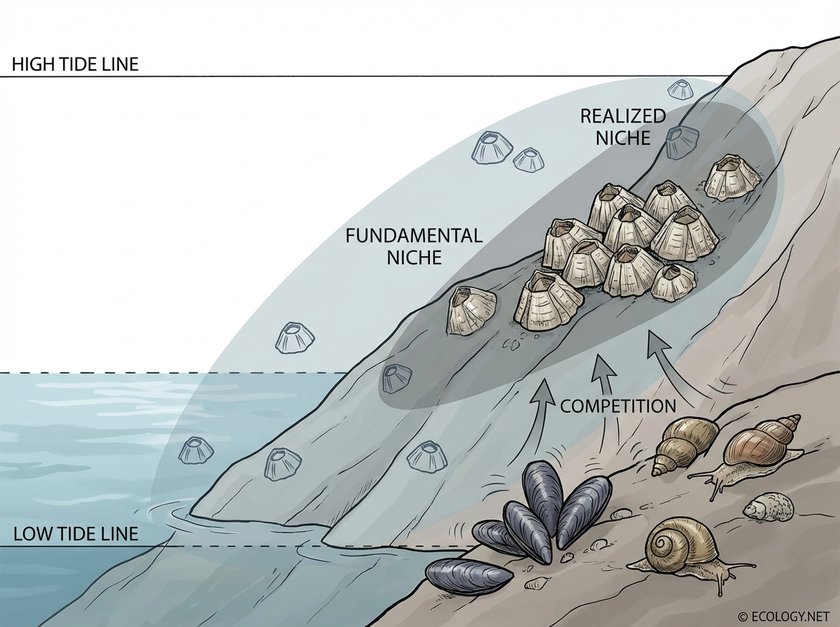

Ecologists often distinguish between two important types of niches: the fundamental niche and the realized niche.

- Fundamental Niche: This represents the full range of environmental conditions and resources that a species could potentially use and occupy if there were no limiting factors such as competition or predation from other species. It is the theoretical maximum niche a species can inhabit based purely on its physiological tolerances and resource needs.

- Realized Niche: This is the actual set of environmental conditions and resources that a species actually occupies and utilizes in the presence of biotic interactions like competition, predation, and disease. The realized niche is often smaller and more restricted than the fundamental niche because of these ecological pressures.

A classic example involves barnacles in the intertidal zone. One species might physiologically be able to survive across a wide range of the shore (its fundamental niche). However, due to competition from another barnacle species that is better adapted to the lower, wetter parts of the shore, the first species might only be found higher up, in a narrower band (its realized niche). The competition effectively “pushes” the species into a smaller, less ideal space.

Niche Partitioning: The Art of Coexistence

One of the most fascinating aspects of ecological niches is how they allow multiple species to coexist in the same habitat without one outcompeting and eliminating the others. This phenomenon is known as niche partitioning or resource partitioning.

The competitive exclusion principle states that two species cannot occupy exactly the same niche in the same habitat at the same time. If they do, one will inevitably outcompete the other, leading to the exclusion of the less successful species.

To avoid direct competition, species often evolve to specialize, dividing up resources or utilizing them in different ways. This can manifest in various forms:

- Spatial Partitioning: Species use different physical areas within the habitat. For example, different bird species might feed at different heights in the same tree.

- Temporal Partitioning: Species use the same resources but at different times. Some animals are nocturnal, while others are diurnal, avoiding direct competition for food.

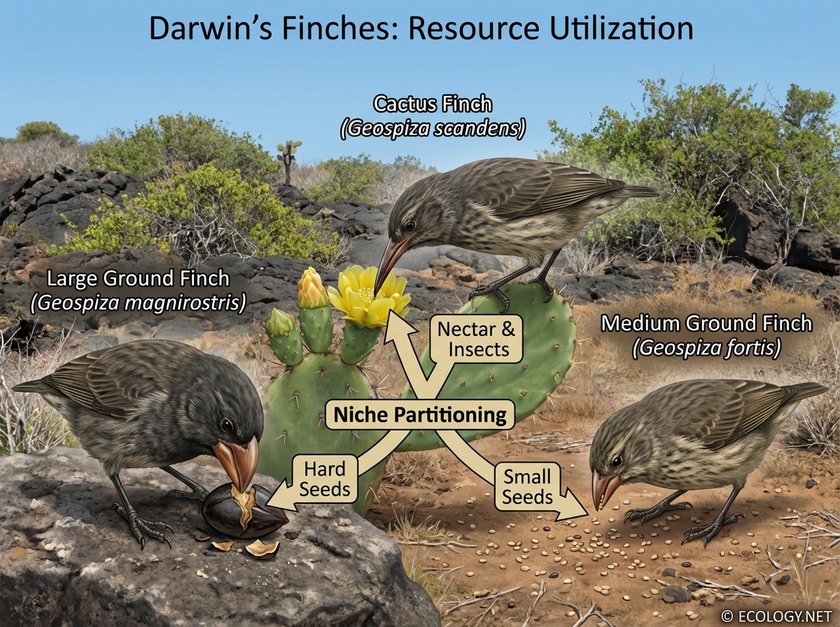

- Resource Partitioning: Species specialize in different types of resources. This is famously seen in Darwin’s finches on the Galapagos Islands. Different finch species have evolved distinct beak shapes that allow them to specialize in eating different types of seeds or insects, thus minimizing direct competition for food.

Imagine the diverse finches of the Galapagos. One species might have a large, strong beak perfect for cracking hard seeds, while another possesses a slender, pointed beak ideal for probing flowers for nectar or catching small insects. A third might have a medium-sized beak suited for smaller seeds. This specialization allows them to share the island’s resources without intense, direct competition, enabling a greater diversity of life.

The Profound Importance of Ecological Niches

Understanding ecological niches is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for conservation, ecosystem management, and our overall comprehension of the natural world.

- Biodiversity Maintenance: Niche partitioning is a primary mechanism that allows for high biodiversity. By specializing, more species can coexist in a given area, enriching the ecosystem.

- Ecosystem Health and Stability: When species occupy distinct niches, the ecosystem is more resilient. If one species declines, others with different niches might not be as affected, preventing a complete collapse of the food web.

- Conservation Efforts: Knowing a species’ niche is crucial for its conservation. It helps identify critical resources, habitat requirements, and potential threats, guiding efforts to protect endangered species.

- Predicting Species Interactions: The concept of niche helps predict how species will interact, especially when new species are introduced or environments change. Species with highly overlapping niches are likely to compete intensely.

Niche Overlap and the Dynamics of Competition

While niche partitioning promotes coexistence, some degree of niche overlap is inevitable. When niches overlap significantly, competition arises. This competition can be direct, such as two animals fighting over a food source, or indirect, where both species deplete a shared resource. The outcome of intense niche overlap can be:

- Competitive Exclusion: One species outcompetes and eliminates the other from the local area.

- Resource Partitioning: Over evolutionary time, species may adapt to reduce overlap, leading to niche partitioning.

- Character Displacement: Species evolve physical or behavioral differences to minimize competition, such as changes in beak size or feeding times.

The Dynamic Nature of Niches

It is important to remember that ecological niches are not static. They can change over time due to various factors:

- Environmental Shifts: Climate change, habitat destruction, or natural disasters can alter available resources and conditions, forcing species to adapt their niches or face decline.

- Evolutionary Adaptation: Over generations, species can evolve new traits that allow them to exploit different resources or tolerate new conditions, effectively shifting their niche.

- Species Introductions: The arrival of an invasive species can drastically alter the niches of native species, often leading to intense competition and displacement.

Conclusion: The Intricate Web of Life

The ecological niche is a powerful concept that moves beyond simply where an organism lives to encompass its entire way of life, its role, and its interactions within the ecosystem. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every living thing occupies a unique niche, a specialized profession that contributes to the grand, interconnected web of life. By appreciating the nuances of fundamental versus realized niches, and the elegant solutions of niche partitioning, we gain a deeper understanding of biodiversity, the delicate balance of nature, and our own place within this magnificent ecological tapestry.