The Silent Killer Beneath the Waves: Understanding Ocean Dead Zones

Imagine an underwater world where life struggles to breathe, where vibrant ecosystems turn barren, and where fish and marine creatures flee or perish. This is not a scene from a dystopian novel, but a stark reality unfolding in many coastal waters around the globe, driven by phenomena known as “dead zones.” These areas, scientifically termed hypoxic zones, are regions of the ocean or large lakes where oxygen levels become so critically low that most marine life cannot survive. Far from being natural occurrences, the proliferation of dead zones is a profound environmental challenge, largely a consequence of human activities. Understanding their formation, impact, and potential solutions is crucial for safeguarding our planet’s aquatic health.

What Exactly is a Dead Zone?

At its core, a dead zone is an area of water with insufficient oxygen to support most marine life. While some natural variations in oxygen levels occur, the dead zones we observe today are characterized by severe, prolonged oxygen depletion, often leading to mass mortality events for fish, shellfish, and other organisms that cannot escape. These zones are not static; they can expand and contract with seasons and environmental conditions, but their increasing frequency and size are a cause for significant concern.

The Unseen Threat: How Dead Zones Form

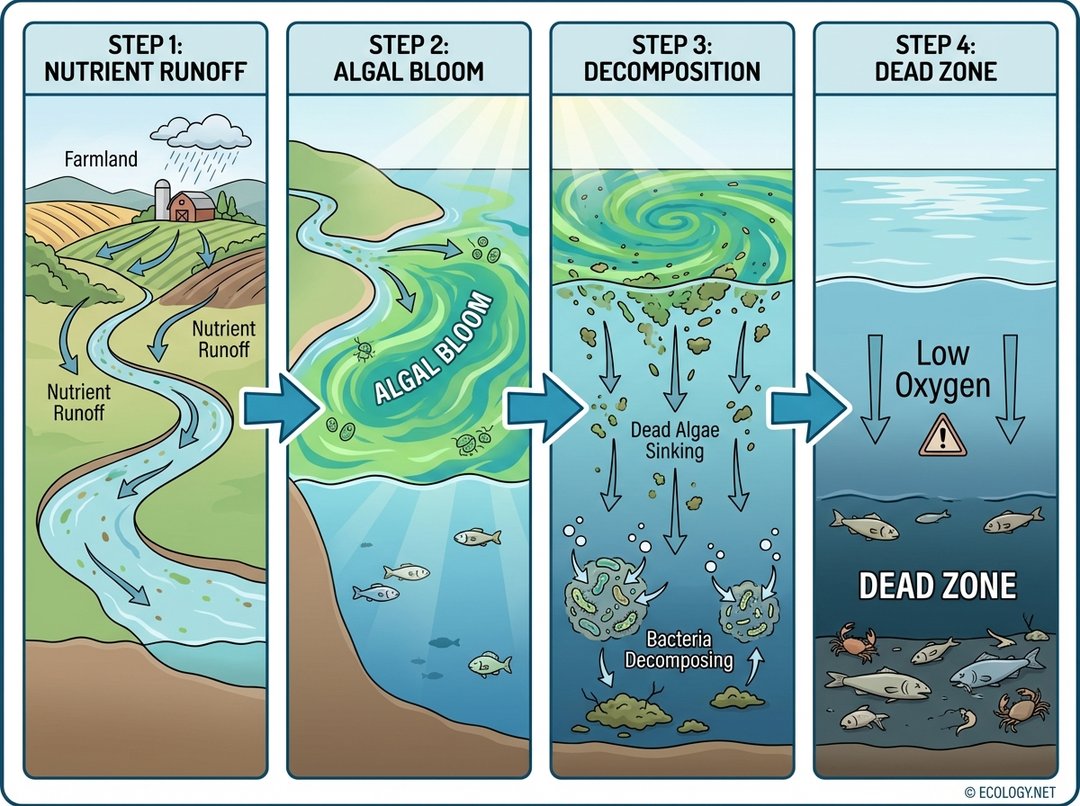

The creation of a dead zone is a complex process, but it primarily stems from an overload of nutrients in coastal waters, coupled with specific physical conditions that prevent oxygen from replenishing.

Nutrient Runoff: The Primary Culprit

The journey to a dead zone often begins far from the ocean, on land. Human activities, particularly agriculture, contribute vast amounts of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into rivers and streams. These nutrients originate from fertilizers used on farms, animal waste, and even inadequately treated wastewater from urban areas.

When these nutrient-rich waters flow into coastal areas, they act like a super-fertilizer for microscopic marine plants called algae. This sudden influx of nutrients triggers an explosive growth spurt, leading to what is known as an “algal bloom.” These blooms can be so dense that they turn the water green or brown, blocking sunlight from reaching seagrasses and other underwater plants, which then die.

While alive, the algae produce oxygen, but their sheer numbers become problematic when they eventually die. The vast quantities of dead algae sink to the bottom, where bacteria begin the process of decomposition. Just like humans, these bacteria need oxygen to break down organic matter. With an abundance of dead algae, the bacterial population explodes, consuming oxygen from the surrounding water at an alarming rate. This rapid consumption of oxygen in the bottom waters is the critical step that leads to hypoxia, or extremely low oxygen levels, creating the dead zone.

For example, the notorious dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, one of the largest in the world, is primarily fueled by nutrient runoff from the Mississippi River Basin, which drains agricultural lands across much of the central United States.

Water Stratification: A Recipe for Disaster

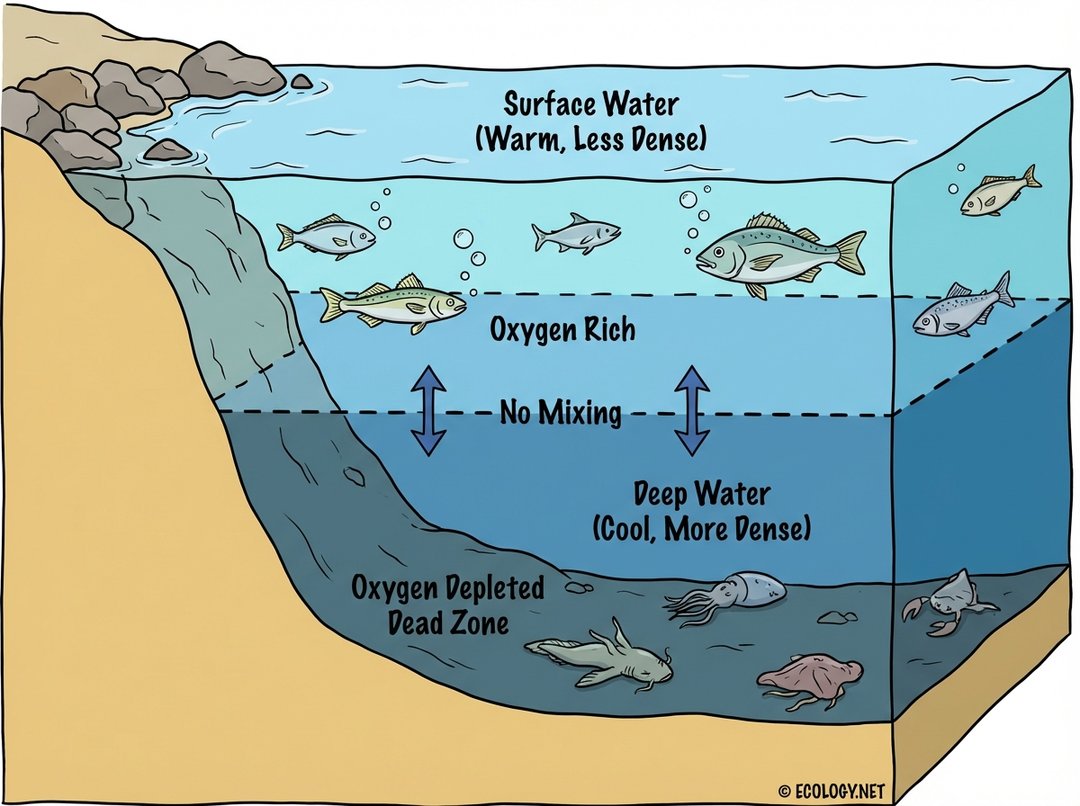

While nutrient runoff initiates the oxygen depletion, another crucial factor often exacerbates the problem: water stratification. This phenomenon occurs when layers of water with different densities, typically due to variations in temperature or salinity, form distinct layers that do not easily mix.

In many coastal regions, especially during warmer months, the sun heats the surface water, making it less dense. Cooler, denser water remains at the bottom. This difference in density creates a barrier, preventing the oxygen-rich surface water from mixing with the deeper layers. Consequently, as bacteria consume oxygen in the bottom waters, there is no fresh oxygen from the surface to replenish it. The deeper water becomes trapped, slowly suffocating as its oxygen supply dwindles.

Consider a layered cake where each layer is distinct and does not blend. Similarly, stratified water bodies prevent the vital exchange of gases, trapping oxygen at the surface and allowing the deeper layers to become increasingly anoxic. This is particularly common in estuaries and coastal seas where freshwater runoff meets saltwater, creating salinity gradients that further enhance stratification.

The Devastating Impact: Life Without Oxygen

The consequences of dead zones are far-reaching, impacting marine ecosystems, biodiversity, and human economies.

Marine Life Suffocation and Displacement

The most immediate and visible impact of a dead zone is the suffocation and displacement of marine life. Organisms that cannot tolerate low oxygen levels, such as many species of fish, crabs, and shrimp, either flee the area or die. Bottom-dwelling creatures, including oysters, clams, and various worms, are particularly vulnerable as they cannot escape the hypoxic conditions.

The loss of these species disrupts the entire food web. Predators that rely on these organisms for food face scarcity, leading to cascading effects throughout the ecosystem. For instance, a decline in commercially important fish or shellfish populations can devastate local fishing industries, impacting livelihoods and food security. The Chesapeake Bay, for example, has seen significant declines in its oyster and blue crab populations due to persistent dead zones.

Beyond the Benthic Zone: Wider Ecological Ripples

The impact of dead zones extends beyond the immediate area of oxygen depletion. Migratory species may alter their routes to avoid these zones, potentially leading to overcrowding in other areas or disrupting their breeding and feeding patterns. The overall biodiversity of affected regions diminishes, leading to less resilient ecosystems that are more susceptible to other environmental stressors. Over time, the fundamental structure and function of these marine environments can be irrevocably altered, favoring species that are more tolerant of low oxygen, often at the expense of those that are ecologically or economically valuable.

Where Are Dead Zones Happening? Global Hotspots

Dead zones are not isolated incidents but a global phenomenon, with hundreds identified worldwide. Some of the most prominent examples include:

- The Gulf of Mexico: As mentioned, this is one of the largest, forming annually off the coast of Louisiana and Texas, driven by the Mississippi River.

- The Baltic Sea: Enclosed and shallow, it suffers from extensive dead zones due to agricultural runoff from surrounding European countries and limited water exchange.

- The Black Sea: Historically one of the largest, its dead zones have fluctuated with changes in nutrient inputs from surrounding nations.

- Chesapeake Bay: A large estuary on the East Coast of the United States, it experiences seasonal dead zones primarily from nutrient pollution originating from surrounding states.

- Coastal areas of East Asia: Rapid industrialization and agricultural expansion in countries like China and South Korea have led to increasing dead zones in their coastal waters.

These examples highlight a common thread: dead zones tend to form in semi-enclosed coastal areas, estuaries, and shallow seas where nutrient inputs are high and water circulation is restricted.

Tackling the Problem: Solutions and Strategies

Addressing the challenge of dead zones requires a multi-faceted approach, focusing on reducing nutrient pollution at its source and improving water quality.

Agricultural Best Practices

Since agriculture is a major contributor to nutrient runoff, implementing sustainable farming practices is paramount. These include:

- Precision agriculture: Applying fertilizers more efficiently, only where and when needed, reduces excess runoff.

- Cover crops: Planting non-cash crops during off-seasons helps absorb leftover nutrients in the soil, preventing them from washing into waterways.

- Riparian buffers: Establishing vegetated buffer zones along rivers and streams filters out nutrients before they reach the water.

- Improved manure management: Proper storage and application of animal waste can significantly reduce nutrient leakage.

Wastewater Treatment Upgrades

Modernizing and upgrading municipal wastewater treatment plants to include advanced nutrient removal technologies can drastically reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus discharged into rivers and coastal waters. This involves processes that specifically target and remove these elements from treated effluent.

Urban and Stormwater Management

Urban areas also contribute to nutrient pollution through stormwater runoff carrying pollutants from impervious surfaces. Solutions include:

- Green infrastructure: Implementing features like rain gardens, permeable pavements, and green roofs helps absorb and filter stormwater before it enters drainage systems.

- Reduced impervious surfaces: Minimizing concrete and asphalt allows more rainwater to infiltrate the ground naturally.

International Cooperation and Policy

Given that many dead zones are fed by rivers crossing multiple jurisdictions or international borders, collaborative efforts and strong environmental policies are essential. International agreements and regional management plans can coordinate efforts to reduce nutrient loads across entire watersheds, ensuring a more holistic and effective approach.

The phenomenon of dead zones serves as a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of our terrestrial and aquatic environments. While the sight of a lifeless ocean floor is a grim prospect, the knowledge we have gained about their formation also empowers us with the solutions needed to reverse this trend. By embracing sustainable practices in agriculture, improving our urban infrastructure, and fostering global cooperation, we can restore the vitality of our coastal waters and ensure that marine life can once again breathe freely beneath the waves. The future of our oceans, and the life within them, depends on our collective action.