Imagine Earth as a living, breathing entity. Just like our bodies have a circulatory system that transports vital nutrients, our planet possesses an intricate system that moves a fundamental element essential for all life: carbon. This planetary circulation is known as the carbon cycle, a dynamic process that governs Earth’s climate, supports ecosystems, and underpins the very existence of life as we know it.

Understanding the carbon cycle is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for comprehending the profound environmental changes our world is currently experiencing. From the air we breathe to the food we eat, carbon is everywhere, constantly moving and transforming. Let us embark on a journey to unravel the mysteries of this essential global process.

The Basics: Carbon Reservoirs and Fluxes

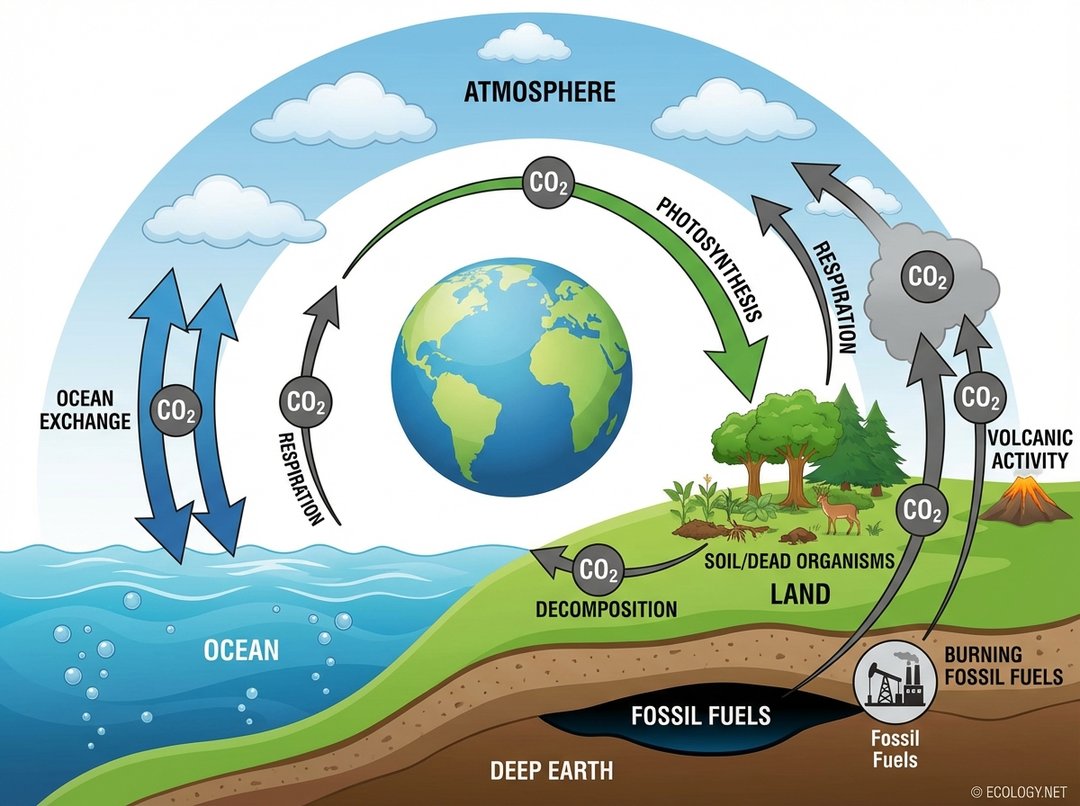

The carbon cycle can be thought of as a grand, interconnected network of reservoirs where carbon is stored and fluxes, which are the processes that move carbon between these reservoirs. These reservoirs hold carbon for varying durations, from days to millions of years.

The primary carbon reservoirs include:

- Atmosphere: Carbon exists primarily as carbon dioxide (CO2) gas. Although a small percentage of the atmosphere, it plays a critical role in regulating Earth’s temperature through the greenhouse effect.

- Oceans: The vast oceans are a massive carbon sink, storing carbon in various forms, including dissolved CO2, carbonic acid, bicarbonate ions, and carbonate ions. Marine organisms also incorporate carbon into their shells and tissues.

- Land: On land, carbon is stored in living organisms (plants, animals, microbes), dead organic matter in soil, and in the soil itself. Forests, in particular, are significant carbon reservoirs.

- Sediments and Rocks: This is the largest, albeit slowest, reservoir. Carbon is locked away in sedimentary rocks like limestone, and in fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas, formed from ancient organic matter over millions of years.

Carbon moves between these reservoirs through various processes, known as fluxes:

- Photosynthesis: Plants and other photosynthetic organisms absorb CO2 from the atmosphere or dissolved in water to create organic compounds.

- Respiration: Living organisms, including plants, animals, and microbes, release CO2 back into the atmosphere or water as they break down organic compounds for energy.

- Decomposition: When organisms die, decomposers (bacteria and fungi) break down organic matter, releasing CO2 into the atmosphere and carbon into the soil.

- Ocean Exchange: CO2 dissolves into and out of the ocean surface, maintaining a dynamic equilibrium with atmospheric CO2. Marine life also plays a significant role in moving carbon through food webs and eventually to the seafloor as sediments.

- Volcanic Activity: Volcanoes release CO2 and other gases from Earth’s interior into the atmosphere, a natural geological flux.

- Burning Fossil Fuels: This human activity releases vast amounts of ancient, stored carbon from geological reservoirs into the atmosphere as CO2.

The Key Processes Driving the Carbon Cycle

To truly appreciate the carbon cycle, we must delve into the fundamental biological and geological processes that orchestrate its movement.

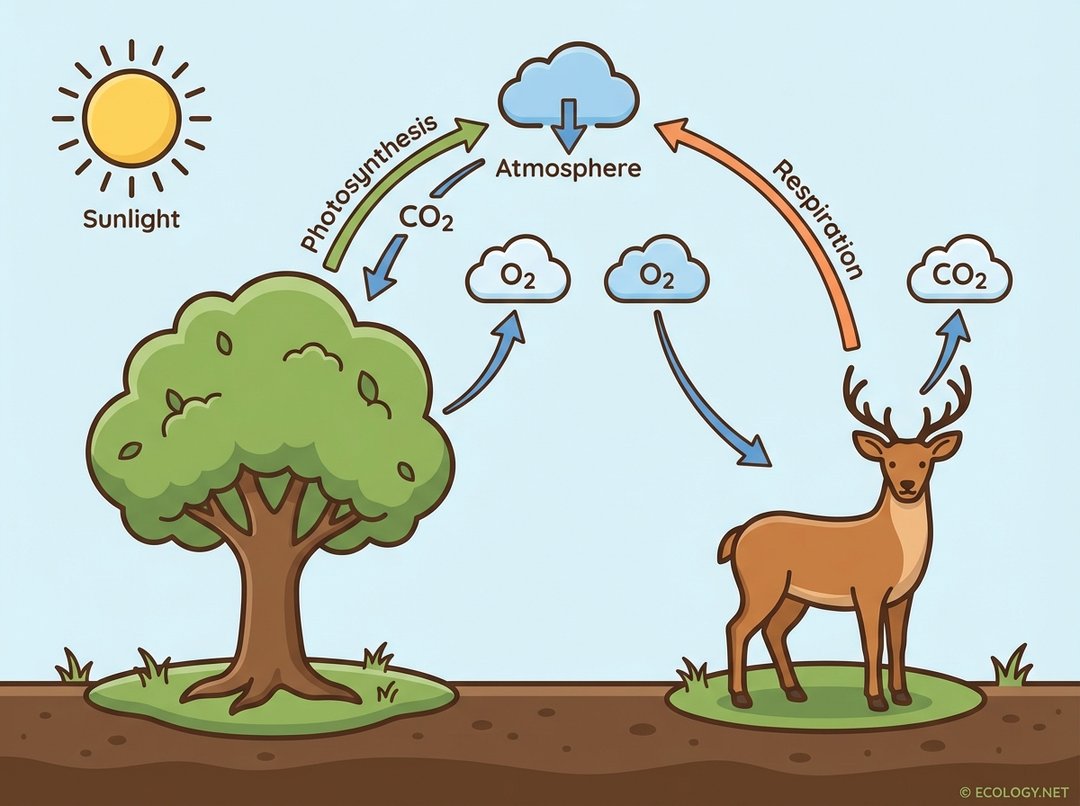

Photosynthesis: Capturing Carbon

At the heart of the biological carbon cycle lies photosynthesis, the miraculous process by which green plants, algae, and some bacteria convert light energy into chemical energy. During photosynthesis, these organisms take in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (or dissolved in water) and water, using sunlight as an energy source, to produce glucose (a sugar) and oxygen.

6CO2 + 6H2O + Light Energy → C6H12O6 + 6O2

This process is the primary way carbon enters the living world. Think of a towering redwood tree; every atom of carbon in its massive trunk, branches, and leaves was once a molecule of CO2 floating in the air, captured by the tree’s photosynthetic machinery. Photosynthesis not only removes CO2 from the atmosphere but also forms the base of nearly all food webs on Earth.

Respiration: Releasing Carbon

The counterpart to photosynthesis is respiration. All living organisms, including plants, animals, and microbes, respire. Respiration is the process by which organisms break down organic compounds (like the glucose produced during photosynthesis) to release energy for their life processes. In aerobic respiration, oxygen is consumed, and carbon dioxide and water are released as byproducts.

C6H12O6 + 6O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O + Energy

Whether it is a deer grazing in a meadow, a bacterium decomposing a fallen leaf, or even the plant itself during the night, respiration continuously returns carbon to the atmosphere and oceans. This balance between photosynthesis and respiration is critical for maintaining stable atmospheric CO2 levels in a natural, undisturbed cycle.

Decomposition: The Earth’s Recycling Crew

When plants and animals die, their organic matter does not simply vanish. It becomes food for decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi. These microscopic organisms break down complex organic compounds into simpler substances, releasing nutrients back into the soil and water. A significant portion of the carbon in this decaying matter is released as CO2 through microbial respiration, returning it to the atmosphere. Without decomposers, carbon would remain locked in dead organic material, and the cycle would grind to a halt.

Oceanic Carbon Dynamics

The ocean is a massive and complex player in the carbon cycle. Carbon dioxide from the atmosphere dissolves into the surface waters of the ocean. Once dissolved, it reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which then dissociates into bicarbonate and carbonate ions. These forms of dissolved inorganic carbon are crucial for marine life.

- Marine Photosynthesis: Phytoplankton, microscopic marine plants, perform photosynthesis, absorbing dissolved CO2 and forming the base of the marine food web.

- Shell Formation: Many marine organisms, such as corals and shellfish, use dissolved carbonate ions to build their shells and skeletons of calcium carbonate. When these organisms die, their shells can sink to the seafloor, forming vast deposits of limestone over geological timescales, effectively locking away carbon.

- Ocean Circulation: Deep ocean currents slowly transport carbon-rich waters throughout the global ocean, a process that can take hundreds to thousands of years.

Geological Processes: The Slow Cycle

While biological processes operate on timescales of days to centuries, geological processes move carbon over millions of years. This “slow carbon cycle” involves:

- Sedimentation: Over vast periods, layers of organic matter and calcium carbonate shells accumulate on the seafloor, compacting into sedimentary rocks like shale and limestone.

- Fossil Fuel Formation: Under specific conditions of high pressure and temperature, ancient organic matter buried in sediments can transform into fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), storing carbon for millions of years.

- Volcanism and Weathering: Carbon locked in rocks can be released back into the atmosphere through volcanic eruptions. Conversely, the weathering of rocks (e.g., the dissolution of limestone by acidic rain) can release carbon into rivers and eventually the ocean.

Human Impacts on the Carbon Cycle

For millennia, the carbon cycle maintained a relatively stable balance, with natural fluxes largely offsetting each other. However, in recent centuries, human activities have significantly altered this delicate equilibrium, primarily by accelerating the release of carbon into the atmosphere.

Burning of Fossil Fuels

The most significant human impact comes from the combustion of fossil fuels. When we burn coal, oil, and natural gas for energy (electricity, transportation, industry), we release carbon that has been stored underground for millions of years back into the atmosphere as CO2. This is akin to opening a very old, very large carbon vault and rapidly emptying its contents into the air.

- Industrial Revolution: The widespread adoption of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution has led to a dramatic increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations, far exceeding natural levels seen in hundreds of thousands of years.

- Energy Demand: Our modern society’s insatiable demand for energy continues to drive this release, with consequences for the global climate.

Deforestation and Land Use Change

Another major contributor to increased atmospheric carbon is deforestation. Forests are vital carbon sinks, absorbing CO2 through photosynthesis and storing large amounts of carbon in their biomass (wood, leaves, roots) and in the soil beneath them. When forests are cleared, especially through burning, the stored carbon is released back into the atmosphere as CO2. Furthermore, the removal of trees reduces Earth’s capacity to absorb CO2 in the future.

- Agricultural Expansion: Land is often cleared for agriculture, livestock grazing, or urban development.

- Reduced Carbon Uptake: The loss of forests means less CO2 is removed from the atmosphere, exacerbating the problem.

Consequences of an Imbalanced Cycle

The rapid increase in atmospheric CO2 due to human activities has profound consequences:

- Climate Change: CO2 is a potent greenhouse gas. Higher concentrations trap more heat in Earth’s atmosphere, leading to global warming and disruptions in weather patterns, sea levels, and ecosystems.

- Ocean Acidification: As the ocean absorbs more CO2 from the atmosphere, it becomes more acidic. This change in pH threatens marine organisms, particularly those that build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate, such as corals, oysters, and pteropods.

The Future of the Carbon Cycle

Understanding the carbon cycle is not just about identifying problems; it is about finding solutions. Mitigating human impact requires a global effort to reduce carbon emissions and enhance natural carbon sinks.

- Transition to Renewable Energy: Shifting away from fossil fuels to sources like solar, wind, and hydroelectric power can drastically reduce CO2 emissions.

- Reforestation and Afforestation: Planting new trees and restoring degraded forests can help absorb excess atmospheric carbon.

- Sustainable Land Management: Practices that improve soil health can increase carbon storage in agricultural lands.

- Technological Solutions: Developing technologies for carbon capture and storage, though still nascent, may play a role in reducing emissions from industrial sources.

Conclusion

The carbon cycle is a magnificent and essential planetary system, a testament to the intricate interconnectedness of Earth’s living and non-living components. From the microscopic phytoplankton in the ocean to the towering trees of ancient forests, every part plays a role in this grand circulation. While human activities have undeniably disrupted this delicate balance, our understanding of the carbon cycle also empowers us to seek solutions and strive for a more sustainable future. By respecting and working with Earth’s natural processes, we can help restore the equilibrium of this vital cycle, ensuring a healthy planet for generations to come.