Unveiling Biomass: The Living Fabric of Our World

Imagine the sheer weight of all life on Earth. From the towering redwoods to the microscopic bacteria teeming in the soil, every living organism, and even recently deceased organic matter, contributes to a fundamental ecological concept known as biomass. It is the very fabric of life, a critical measure that helps scientists understand ecosystems, track energy flow, and even develop sustainable resources for the future.

But what exactly is biomass, and why is it so important? Join us on a journey to explore this vital concept, from its basic definition to its profound implications for our planet.

What Exactly Is Biomass? Defining Life’s Mass

At its core, biomass refers to the total mass of organic matter within a given area or ecosystem. This includes all living organisms, such as plants, animals, and microorganisms, as well as dead organic material like fallen leaves, decaying wood, and animal waste. It is essentially the sum total of all biological material.

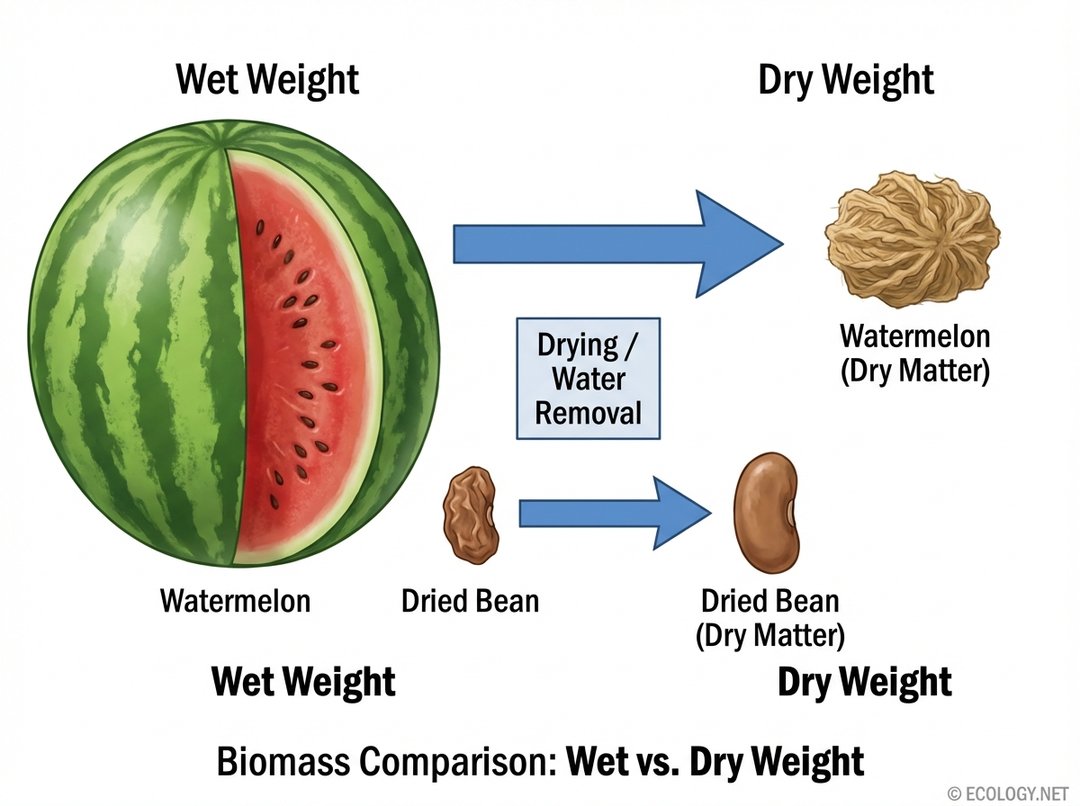

However, when ecologists talk about biomass, they often refer to a very specific measurement: dry weight biomass. Why dry weight? Because water content can vary wildly between organisms and even within the same organism at different times. A juicy fruit, for instance, is mostly water, while a dried seed is predominantly solid matter. To get an accurate, comparable measure of the actual organic material, the water is removed.

Consider a large, succulent watermelon and a tiny, shriveled dried bean. If you weighed them as they are, the watermelon would be far heavier. But if you were to remove all the water from both, you might find that the watermelon’s remaining dry matter is proportionally much smaller than its original wet weight, while the dried bean’s dry matter is a significant portion of its initial mass. This dry weight provides a consistent basis for comparison, revealing the true amount of organic material available.

Why Does Dry Weight Matter So Much?

- Consistency: It eliminates the variability caused by water content, allowing for standardized comparisons across different species and environments.

- Energy Content: The dry organic matter is what holds the stored chemical energy that fuels ecosystems. Water, while essential for life, does not contribute to this energy content.

- Resource Assessment: When evaluating biomass as a resource, such as for bioenergy, the dry weight is the crucial factor determining its potential yield.

Why Biomass Matters: The Foundation of Ecosystems

Biomass is far more than just a number; it is a fundamental indicator of an ecosystem’s health, productivity, and capacity to support life. Its significance spans several critical areas:

- Energy Flow: Biomass represents stored solar energy, captured by plants through photosynthesis. This energy then flows through food webs as organisms consume one another, making biomass a direct measure of an ecosystem’s energy reserves.

- Carbon Cycling: Living organisms are massive carbon sinks. Plants absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, converting it into organic compounds that form their biomass. When organisms die and decompose, this carbon can be returned to the soil or atmosphere. Understanding biomass helps us track the global carbon cycle, which is vital for climate regulation.

- Nutrient Cycling: Biomass is a reservoir of essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. As organisms grow, they incorporate these nutrients into their tissues. Decomposition returns these nutrients to the soil, making them available for new life.

- Ecosystem Health: Changes in biomass can signal shifts in an ecosystem. A decline in plant biomass, for example, might indicate drought, disease, or overgrazing, impacting the entire food web.

Types of Biomass: A World of Organic Matter

Biomass can be categorized in various ways, reflecting the immense diversity of life on Earth:

By Organism Type:

- Plant Biomass (Phytomass): This is typically the largest component of biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems. It includes trees, shrubs, grasses, crops, algae, and all other photosynthetic organisms.

- Animal Biomass (Zoomass): Encompasses all animal life, from insects and worms to fish, birds, and mammals. While often less in total mass than plant biomass, it represents a crucial link in energy transfer.

- Microbial Biomass: The collective mass of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other microorganisms. Despite their small size, their sheer numbers mean microbial biomass can be substantial, especially in soils, and they play indispensable roles in decomposition and nutrient cycling.

By Source or Location:

- Forest Biomass: Trees, undergrowth, forest floor litter.

- Agricultural Biomass: Crops, crop residues (straw, stalks), animal manure.

- Aquatic Biomass: Algae, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fish, marine mammals.

- Waste Biomass: Municipal solid waste, industrial organic waste, sewage.

Measuring Biomass: A Scientific Endeavor

Quantifying biomass is a complex task, especially across vast and diverse ecosystems. Scientists employ various methods, each with its own advantages and challenges:

- Direct Measurement (Destructive Sampling): This involves harvesting, drying, and weighing organisms from a defined area. For plants, this might mean cutting down trees or collecting all vegetation from a quadrat. While highly accurate for the sampled area, it is destructive and impractical for large scales.

- Indirect Measurement (Non-Destructive):

- Allometric Equations: For larger organisms like trees, scientists measure easily obtainable parameters (e.g., trunk diameter, height) and use mathematical equations derived from previously destructively sampled individuals to estimate biomass.

- Remote Sensing: Satellite imagery, aerial photography, and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology can estimate vegetation cover, height, and density over vast areas, which are then correlated with biomass.

- Population Estimates: For animal populations, biomass can be estimated by multiplying the average weight of an individual by the estimated number of individuals in a given area.

Biomass Pyramids: The Flow of Life’s Energy

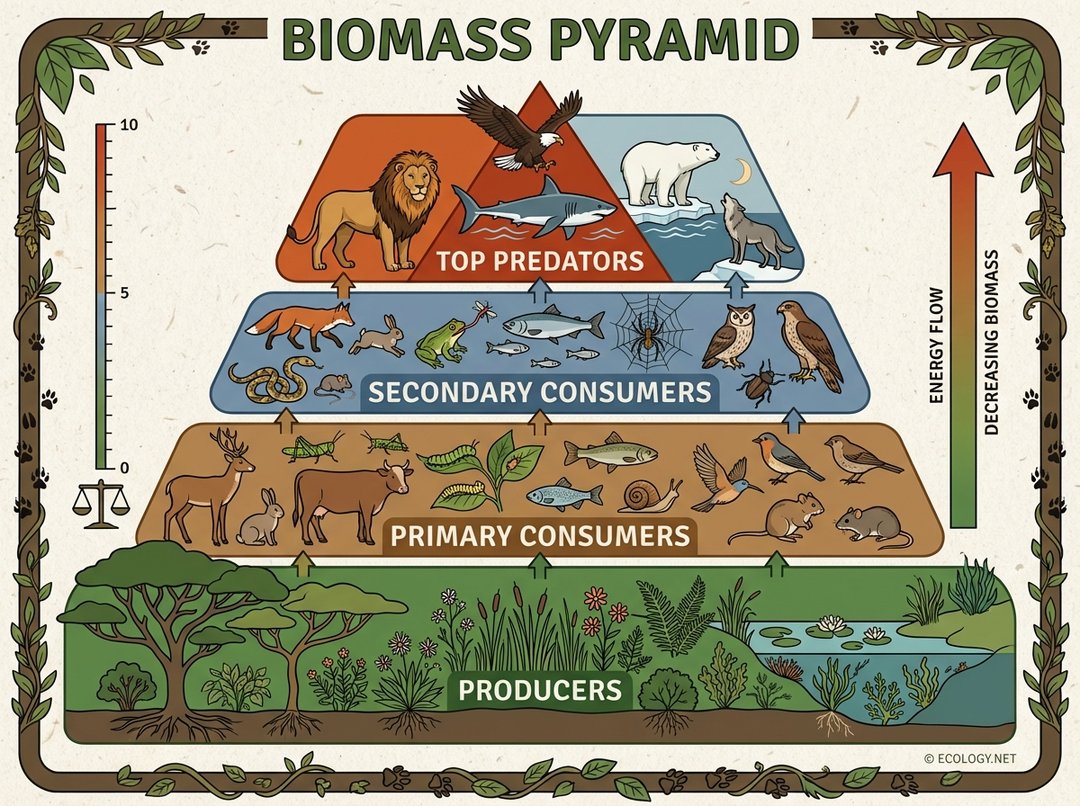

One of the most powerful applications of biomass measurement is in constructing ecological pyramids, which illustrate the quantitative relationships between different trophic levels in an ecosystem. A biomass pyramid specifically shows the total mass of organisms at each level.

In most ecosystems, a classic pyramid shape emerges: the total biomass decreases significantly at each successive trophic level. This is because energy is lost at each transfer, primarily as heat, according to the second law of thermodynamics. Only about 10% of the energy (and thus, the biomass it supports) from one trophic level is typically transferred to the next.

- Producers (Bottom Layer): These are the autotrophs, primarily plants and algae, that convert solar energy into organic matter. They form the widest base of the pyramid, representing the largest total biomass.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Organisms that feed directly on producers. Their total biomass is significantly less than that of the producers they consume.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores/Omnivores): Organisms that feed on primary consumers. Their biomass is even smaller.

- Top Predators (Tertiary Consumers): At the apex of the pyramid, these organisms feed on secondary consumers. They represent the smallest total biomass, requiring a vast base of producers to sustain them.

Understanding these pyramids is crucial for comprehending how energy flows through an ecosystem and the implications of disturbances at any trophic level. For example, a decline in producer biomass can have cascading effects throughout the entire food web.

Biomass as a Resource: Bioenergy and Beyond

Beyond its ecological significance, biomass holds immense potential as a renewable resource, particularly in the realm of energy production and sustainable materials.

Bioenergy: Harnessing Stored Sunlight

Bioenergy refers to energy derived from biomass. Unlike fossil fuels, which are ancient biomass, modern bioenergy utilizes recently living organic matter, making it a potentially renewable source if managed sustainably. Common forms include:

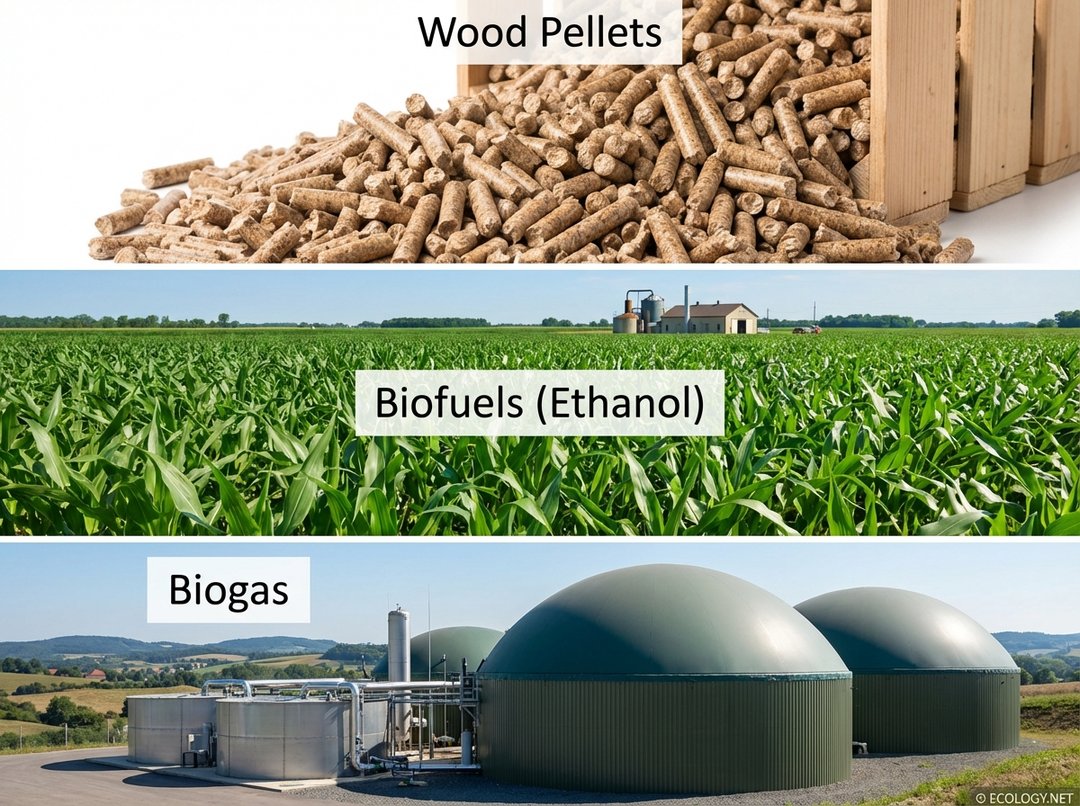

- Solid Biomass: Direct combustion of wood, agricultural residues (like corn stalks or rice husks), and dedicated energy crops (e.g., switchgrass) to produce heat or electricity. Wood pellets, made from compressed sawdust, are a popular example, offering a denser, more uniform fuel.

- Liquid Biofuels:

- Ethanol: Produced by fermenting sugars from crops like corn, sugarcane, or cellulosic materials. It is commonly blended with gasoline for transportation.

- Biodiesel: Made from vegetable oils (soybean, rapeseed) or animal fats through a chemical process called transesterification.

- Gaseous Biofuels (Biogas): Produced through anaerobic digestion, where microorganisms break down organic matter (manure, sewage, food waste) in the absence of oxygen, yielding methane-rich biogas that can be used for heat, electricity, or vehicle fuel.

Beyond Energy: Other Applications of Biomass

Biomass is also a versatile raw material for a wide array of products:

- Building Materials: Timber, bamboo, and engineered wood products.

- Paper and Pulp: Derived from wood fibers.

- Bioplastics: Plastics made from renewable biomass sources like corn starch or sugarcane, offering an alternative to petroleum-based plastics.

- Biochemicals: A vast range of chemicals, from solvents to pharmaceuticals, can be derived from biomass, forming the basis of a bio-based economy.

- Fertilizers: Compost and manure, both forms of biomass, enrich soil and support agricultural productivity.

Challenges and the Future of Biomass

While biomass offers significant potential, its utilization is not without challenges. Sustainability is paramount. Concerns include:

- Land Use Competition: Growing energy crops can compete with food production or natural habitats, leading to deforestation or food price increases.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions: While often considered carbon-neutral (as the carbon released during combustion was recently absorbed by plants), the entire lifecycle, including cultivation, processing, and transport, can have a carbon footprint.

- Efficiency: Converting biomass to energy or other products can be energy-intensive, and improving conversion efficiency is an ongoing area of research.

The future of biomass lies in sustainable management practices, technological innovation, and integration into a circular economy. This includes developing advanced biofuels from non-food sources (like algae or agricultural waste), improving biorefinery technologies to extract maximum value from biomass, and ensuring that biomass harvesting does not deplete natural resources or harm biodiversity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Biomass

From the smallest microbe to the largest forest, biomass is a testament to the sheer volume and diversity of life on Earth. It is the currency of energy in ecosystems, a vital component of global cycles, and a promising resource for a more sustainable future. Understanding biomass allows us to appreciate the intricate web of life, make informed decisions about resource management, and innovate towards a world where human needs are met in harmony with nature. As we continue to explore and utilize this living fabric of our world, the principles of ecological balance and sustainability will remain our guiding stars.