The Allee Effect: When Small Numbers Spell Big Trouble for Populations

In the intricate dance of life, population growth is often depicted as a straightforward affair: more individuals mean more reproduction, leading to an ever-increasing population until resources run out. This concept, known as density dependence, suggests that as a population grows, competition for resources intensifies, eventually slowing growth. However, nature often throws a curveball, revealing a counter-intuitive phenomenon where small populations struggle not because of too much competition, but because there are simply too few individuals. This is the fascinating and often perilous world of the Allee effect.

The Allee effect describes a situation where an individual’s fitness, or its ability to survive and reproduce, increases with population density. In simpler terms, for certain species, having more neighbors is actually beneficial, and being part of a very small group can be a significant disadvantage, making survival and growth incredibly difficult. This stands in stark contrast to the more commonly understood density-dependent factors that typically limit large populations.

Why Do Small Populations Struggle? Unpacking the Mechanisms

The challenges faced by small populations due to the Allee effect are diverse, stemming from various ecological and behavioral mechanisms. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for appreciating the full impact of this phenomenon.

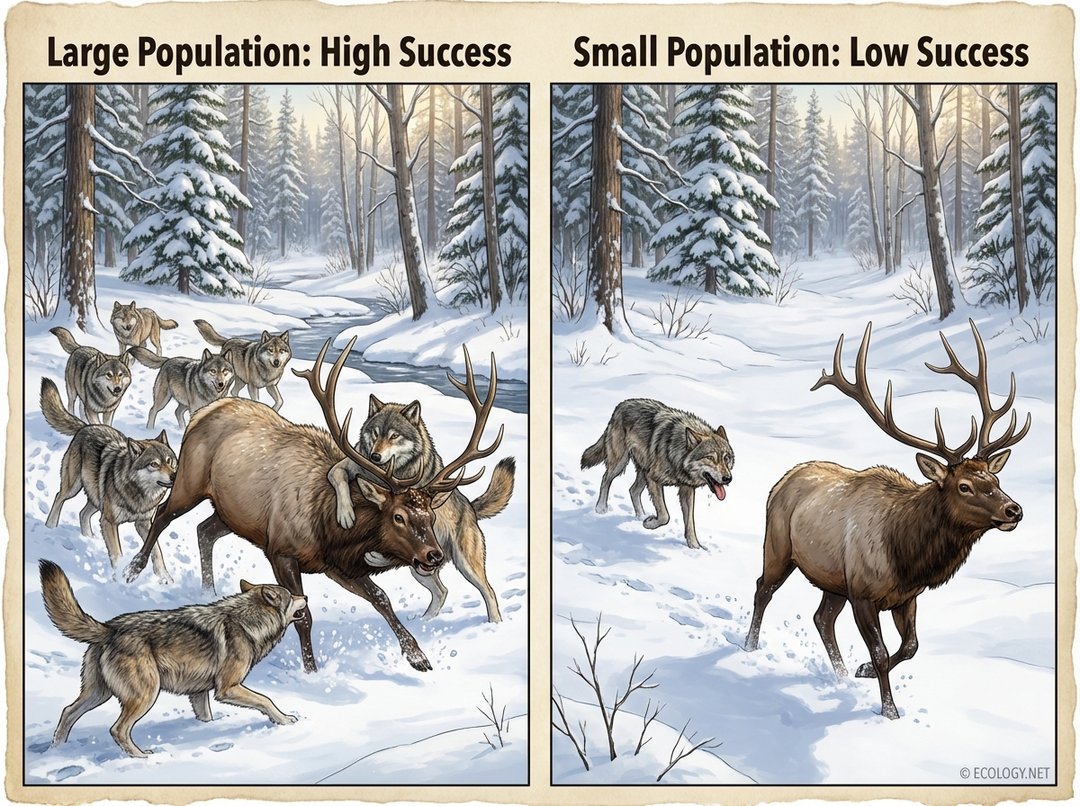

1. The Power of Cooperation: Safety and Success in Numbers

Many species rely on group activities for survival, whether it is hunting, foraging, or defending against predators. When a population shrinks, the ability to perform these cooperative behaviors effectively diminishes, leading to reduced success rates for individuals.

Consider a pack of wolves. A large, coordinated pack can successfully hunt large prey like elk, ensuring a consistent food supply for its members. Each wolf benefits from the collective effort, increasing its chances of survival and reproduction. However, if the pack size dwindles to just a few individuals, or even a single wolf, hunting large prey becomes an almost impossible task. The lone wolf struggles, expending immense energy with little reward, highlighting how cooperative behaviors like hunting become less effective as population size decreases, making it harder for small populations to survive and grow. This reduction in hunting success directly impacts the fitness of the remaining individuals.

Other examples include:

- Group Defense: Many fish school or birds flock to confuse predators. A lone individual or a very small group offers an easy target.

- Cooperative Breeding: Some bird species, like meerkats, rely on helpers to raise young, guard nests, or forage. Without enough helpers, breeding success plummets.

- Foraging Efficiency: Bees communicate food sources, and ants work together to carry large items. Fewer individuals mean less efficient resource acquisition.

2. The Challenge of Mate Finding: A Lonely Endeavor

Perhaps one of the most intuitive mechanisms of the Allee effect is the difficulty of finding a mate when individuals are few and far between. In a sparse population, individuals may spend significant time and energy searching for a partner, or may simply fail to find one altogether.

Imagine a vast, fragmented forest where only a handful of giant pandas remain. A single, isolated panda might wander for years without encountering another of its kind, leading to reproductive failure. This image illustrates a demographic Allee effect mechanism, specifically the challenge of mate finding. It visually contrasts a sparse population where individuals struggle to locate partners with a denser population where reproduction is more feasible, emphasizing a key reason small populations decline. Conversely, in a denser population, encounters are more frequent, and successful reproduction is more likely. This challenge is particularly acute for species with specific mating rituals, limited mobility, or short reproductive windows.

3. Environmental Conditioning and Habitat Modification

Some species actively modify their environment to make it more suitable for themselves and their offspring. When populations are small, this ability to condition the environment can be lost. For instance, a large colony of beavers can build dams that create wetlands, benefiting numerous species, including themselves. A single beaver, or a very small group, might not be able to construct or maintain such complex structures, leading to a degraded habitat and reduced survival. Similarly, large groups of plants can alter soil composition or create microclimates that favor their growth, a benefit lost in sparse stands.

4. Predator Satiation and Dilution Effect

In large groups, the risk of any single individual being eaten by a predator can decrease. This is known as the dilution effect. If a predator attacks a flock of a thousand birds, each bird has a 1 in 1000 chance of being the victim. If the flock is only ten birds, each has a 1 in 10 chance. Furthermore, very large populations can sometimes “satiate” predators, meaning there are simply too many prey individuals for predators to consume them all, allowing a significant portion of the population to survive. Small populations offer no such protection.

Strong vs. Weak Allee Effect: A Critical Distinction

The Allee effect is not a monolithic concept; it manifests in different forms with varying degrees of severity. Ecologists distinguish between two main types: the weak Allee effect and the strong Allee effect. This distinction is crucial because it determines whether a population faces an immediate threat of extinction due to low numbers.

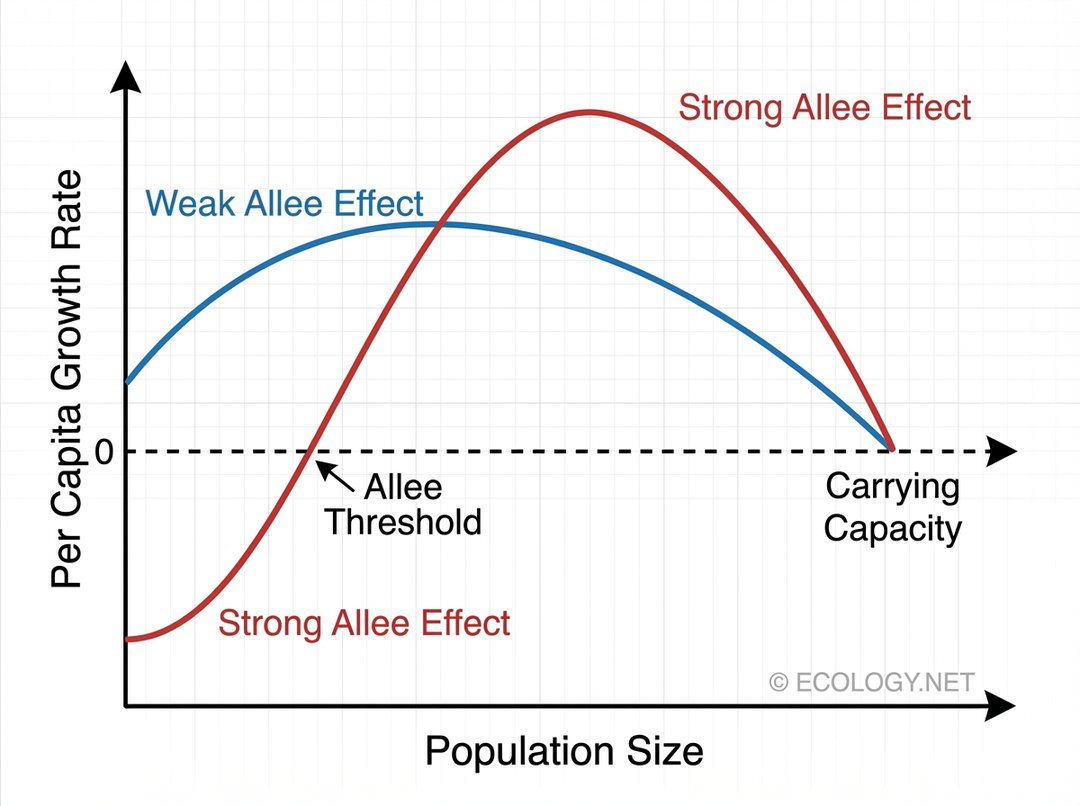

This diagram visually explains the difference between weak and strong Allee effects by showing how the per capita growth rate changes with population size, highlighting the critical “Allee Threshold” where populations with a strong Allee effect face extinction.

- Weak Allee Effect: In a weak Allee effect, the per capita growth rate (the average number of offspring produced per individual) is reduced at low population densities, but it remains positive. This means that even at very low numbers, the population can still grow, albeit slowly. While small populations are disadvantaged, they do not face an immediate extinction vortex solely due to low numbers. Their growth rate simply increases as the population grows, eventually peaking before declining due to typical density-dependent factors.

- Strong Allee Effect: This is the more perilous scenario. With a strong Allee effect, the per capita growth rate becomes negative at very low population densities. This means that below a certain critical population size, known as the Allee Threshold, the population will inevitably decline towards extinction, even if environmental conditions are otherwise favorable. The population simply cannot produce enough offspring to replace the individuals that die, leading to a downward spiral. The Allee Threshold represents a point of no return; once a population falls below it, its fate is often sealed without intervention.

Real-World Examples of the Allee Effect in Action

The Allee effect is observed across a wide range of species and ecosystems, underscoring its broad ecological relevance.

- African Wild Dogs: These highly social predators rely on pack hunting. Small packs are less successful at bringing down prey, leading to lower reproductive rates and higher mortality. This is a classic example of a strong Allee effect.

- Passenger Pigeons: Once numbering in the billions, these birds relied on massive flocks for predator defense and successful breeding. As their numbers were decimated by hunting, their ability to form these crucial large flocks disappeared, leading to a rapid and irreversible decline, even for remaining small populations.

- Marine Fish Stocks: For some commercially exploited fish, once populations drop below a certain threshold, the ability to find mates or form protective schools is compromised, hindering recovery even after fishing pressure is reduced.

- Plants: Many plant species rely on pollinators. In sparse plant populations, pollinators may be less likely to visit, leading to reduced seed set and reproductive failure. This is particularly true for species requiring cross-pollination.

- Invasive Species: Interestingly, the Allee effect can also explain why some invasive species struggle to establish themselves when only a few individuals are introduced. If they cannot find mates or form viable groups, the initial small population may fail to take hold.

Implications for Conservation: A Race Against the Threshold

Understanding the Allee effect is paramount for conservation biology. It highlights why simply protecting habitat or reducing direct threats might not be enough to save endangered species if their numbers have already fallen below a critical threshold.

- Setting Conservation Targets: Conservation efforts must aim not just for survival, but for population sizes well above any potential Allee threshold to ensure long-term viability.

- Reintroduction Programs: When reintroducing species into the wild, releasing too few individuals can lead to failure due to the Allee effect. A larger initial release might be necessary to overcome the challenges of small numbers.

- Genetic Diversity: While not a direct mechanism of the Allee effect, small populations are also prone to reduced genetic diversity, which can exacerbate Allee effects by making individuals less fit and less adaptable to environmental changes.

- Monitoring and Intervention: Close monitoring of population sizes is essential to identify species approaching an Allee threshold, allowing for timely intervention before a decline becomes irreversible.

Conclusion: The Hidden Peril of Scarcity

The Allee effect offers a profound insight into the complex dynamics of populations, revealing that for many species, there is indeed safety and success in numbers. It challenges the intuitive notion that any population, no matter how small, can always recover if given the chance. Instead, it paints a picture where scarcity itself can be a powerful driver of extinction, pushing populations into an irreversible decline once they fall below a critical size. By recognizing and understanding the Allee effect, ecologists and conservationists can develop more effective strategies to protect vulnerable species, ensuring that the intricate web of life continues to thrive, not just survive.