The Unseen Architects: How Viruses Shape Life on Earth

When the word “virus” is uttered, most minds immediately conjure images of illness, disease, and microscopic invaders causing harm. This perception, while rooted in valid experiences, represents only a fraction of the viral story. Far from being mere pathogens, viruses are ubiquitous, ancient, and profoundly influential entities that have been shaping the very fabric of life on Earth for billions of years. They are not just agents of disease, but also unseen architects, driving evolution, regulating populations, and orchestrating nutrient cycles across every ecosystem imaginable.

What Exactly Is a Virus?

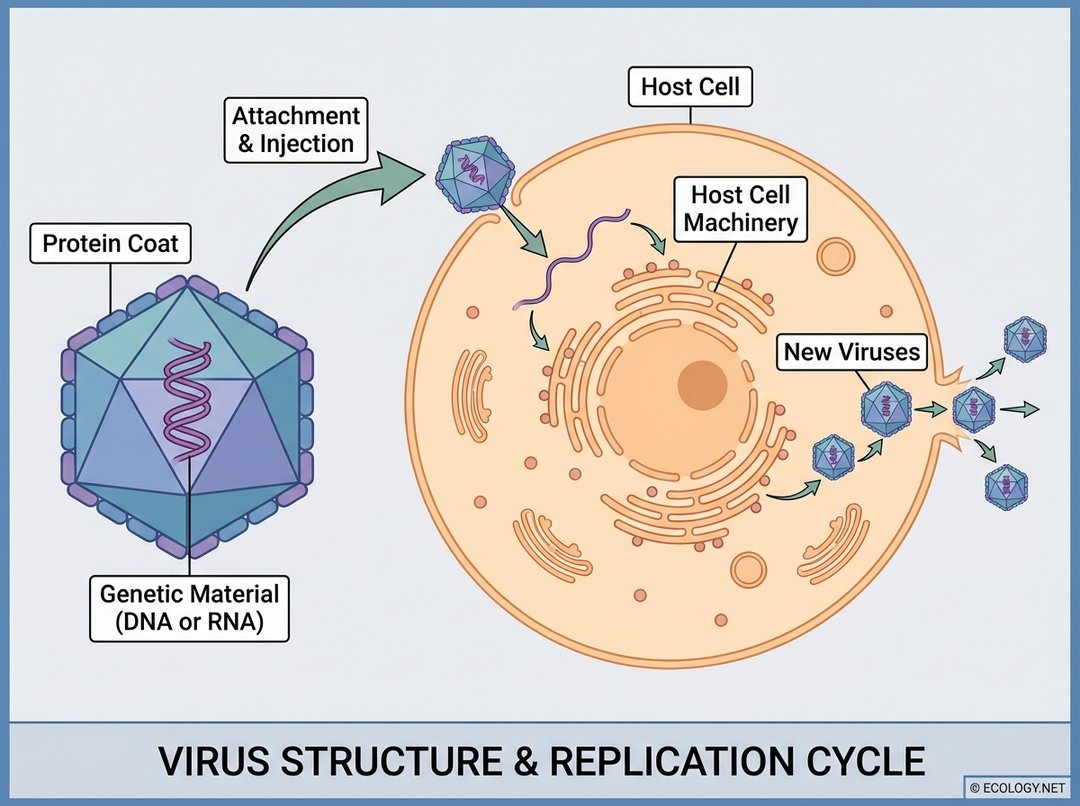

At their most fundamental level, viruses are remarkably simple. They are not cells, nor are they typically considered “alive” in the conventional sense, as they lack the cellular machinery to reproduce independently. Instead, a virus is essentially a package of genetic material, either DNA or RNA, encased within a protective protein coat. Some viruses also possess an outer lipid envelope derived from their host cell.

Their existence hinges entirely on a host. Once a virus encounters a suitable host cell, it attaches, injects its genetic material, and effectively hijacks the cell’s internal machinery. The host cell, unknowingly, becomes a factory, replicating viral genetic material and assembling new virus particles. This obligate parasitic nature is central to understanding their biology and, crucially, their ecological roles. Without a host, a virus is inert, a mere chemical package waiting for its moment to spring to life.

Beyond Disease: Viruses as Ecological Architects

While the disease-causing aspect of viruses is well-known, their ecological contributions are far more pervasive and often beneficial, or at least neutral, from a broader ecosystem perspective. Viruses are not just destroyers; they are also recyclers, regulators, and powerful drivers of genetic innovation.

The Unseen Drivers of Nutrient Cycling

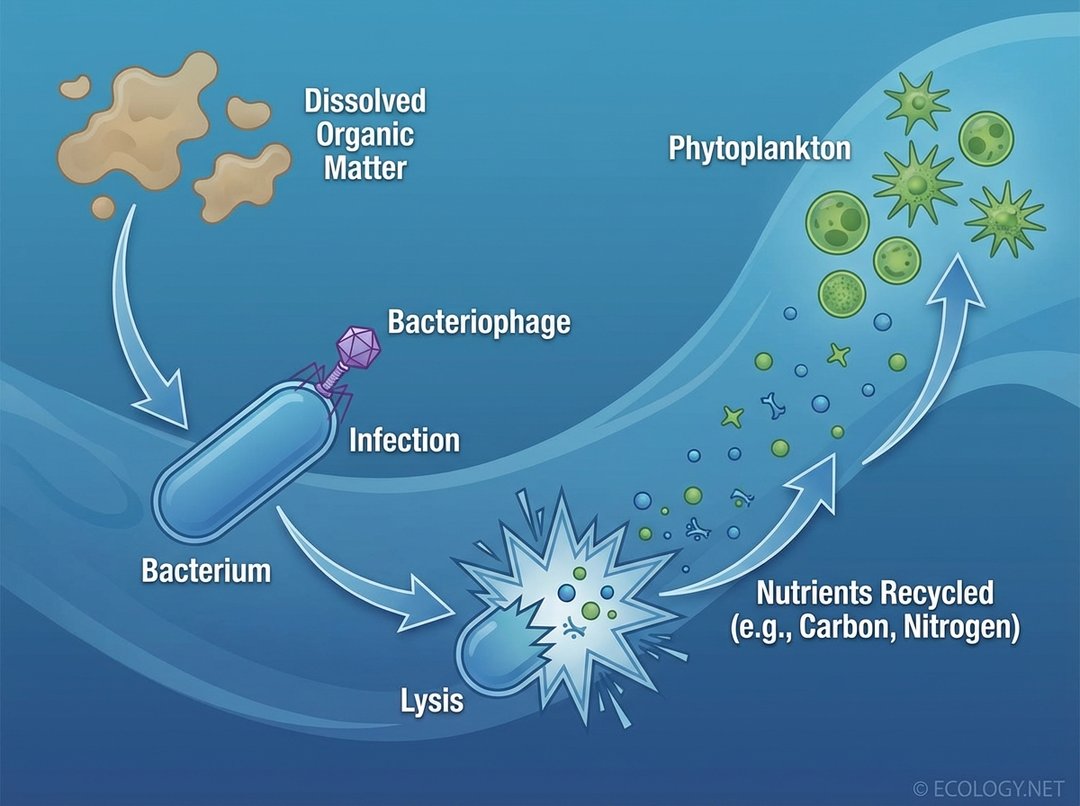

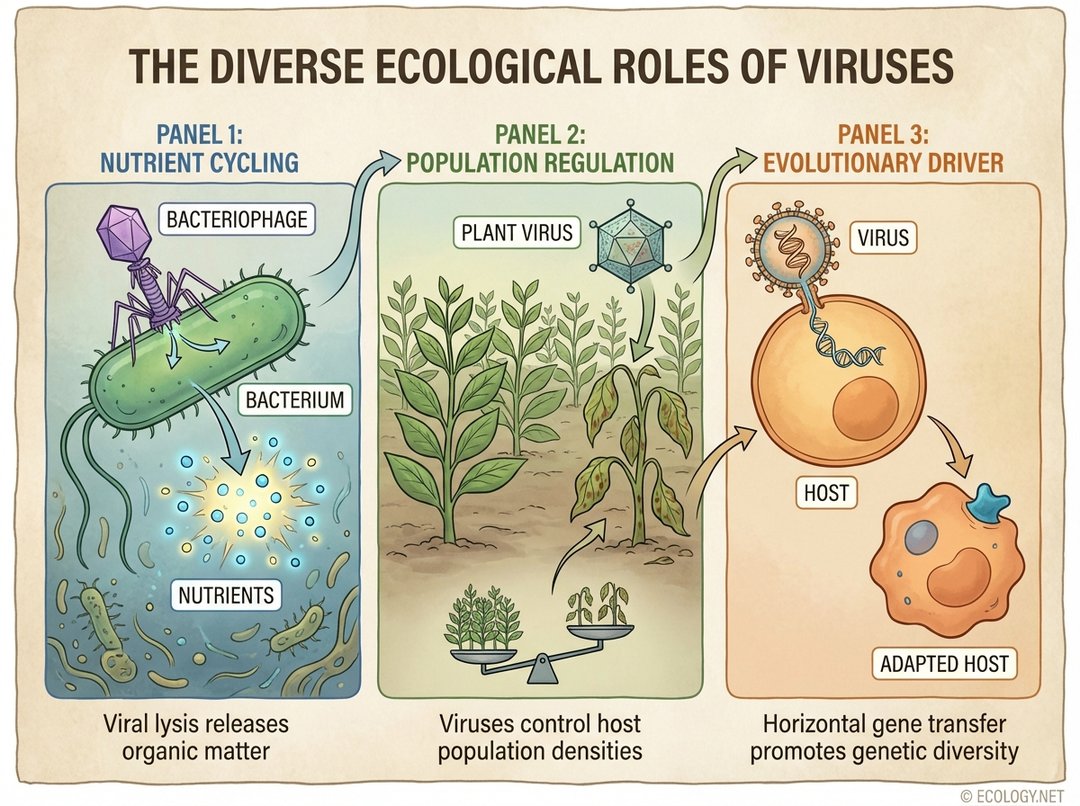

One of the most profound, yet often overlooked, roles of viruses is their involvement in global nutrient cycles, particularly in aquatic environments. Here, bacteriophages, viruses that specifically infect bacteria, are the unsung heroes.

Consider the “microbial loop” in oceans and freshwater bodies. Microscopic organisms like bacteria consume dissolved organic matter, converting it into biomass. However, these bacteria do not live forever. When bacteriophages infect and lyse, or burst, bacterial cells, they release the bacteria’s internal contents back into the water as dissolved organic matter and inorganic nutrients. This process, known as viral lysis, is a continuous and massive event, effectively recycling vast quantities of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other essential elements that would otherwise remain locked within microbial biomass.

Without this viral-mediated recycling, nutrients would become sequestered in microbial populations, limiting their availability for other organisms, such as phytoplankton, which form the base of many aquatic food webs. In essence, phages act as a vital “shunt” in the microbial loop, ensuring that nutrients remain available to fuel primary production and support the entire ecosystem.

Regulators of Life: Population Control

Just as predators regulate prey populations, viruses play a critical role in controlling the numbers of their host organisms, from bacteria to plants and animals. This regulatory function is essential for maintaining ecological balance and preventing any single species from dominating an ecosystem.

- Microbial Populations: In marine environments, viral lysis can decimate massive algal blooms, preventing them from consuming all available nutrients and creating “dead zones” when they decompose. Similarly, phages keep bacterial populations in check, preventing overgrowth and promoting diversity.

- Plant Populations: Plant viruses can spread rapidly through agricultural crops or wild plant communities, influencing their distribution and abundance. While often detrimental to human agriculture, in natural settings, this can prevent monocultures and open niches for other plant species. For example, certain viruses can weaken dominant plant species, allowing less competitive plants to thrive.

- Insect and Animal Populations: Viruses are natural biocontrol agents. Baculoviruses, for instance, are highly specific to certain insect larvae and have been used as biological pesticides. In wild animal populations, viruses can regulate numbers, influencing predator-prey dynamics and overall ecosystem health. The rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus, for example, has significantly impacted wild rabbit populations in Australia and Europe, with cascading effects on their predators and the vegetation they consume.

Engines of Evolution: Shaping Biodiversity

Perhaps the most profound and long-term impact of viruses is their role as drivers of evolution. Viruses are constantly interacting with their hosts, and these interactions often lead to genetic changes that can be passed down through generations.

Viruses are not just agents of disease, but also unseen architects, driving evolution, regulating populations, and orchestrating nutrient cycles across every ecosystem imaginable.

- Horizontal Gene Transfer: Viruses can pick up host genes and transfer them to new hosts, or even integrate their own genetic material into the host genome. This “horizontal gene transfer” is a powerful mechanism for introducing new genetic variation, allowing organisms to adapt to changing environments, develop new traits, or even acquire resistance to other pathogens. For example, some bacteria have acquired genes from phages that provide them with new metabolic capabilities or resistance to antibiotics.

- Endogenous Viral Elements: Over evolutionary time, viral genetic material can become permanently incorporated into the host genome, becoming “endogenous viral elements.” A significant portion of the human genome, for instance, is composed of remnants of ancient viral infections. These viral genes, once integrated, can sometimes be co-opted by the host to perform new functions, influencing everything from immune responses to placental development in mammals.

- Co-evolutionary Arms Races: The constant battle between viruses and their hosts drives an evolutionary arms race. Hosts evolve defenses against viral infection, and viruses evolve new ways to evade these defenses. This dynamic interplay fosters rapid evolution in both viruses and hosts, contributing significantly to biodiversity and the complexity of life.

The Future of Viral Ecology

The field of viral ecology is rapidly expanding, revealing an ever more intricate picture of viruses as fundamental components of Earth’s ecosystems. Advanced genomic techniques are uncovering the immense diversity of the “virosphere” and the myriad ways viruses interact with their hosts and the environment.

Understanding these complex interactions is not merely an academic exercise. It has practical implications for:

- Climate Change Research: Viruses influence the carbon cycle by regulating microbial populations that absorb and release greenhouse gases.

- Biotechnology and Medicine: Phages are being explored as alternatives to antibiotics in the face of rising antimicrobial resistance. Viruses are also powerful tools in gene therapy and vaccine development.

- Ecosystem Management: Recognizing the role of viruses in population regulation can inform conservation efforts and strategies for managing invasive species.

In conclusion, viruses are far more than just agents of disease. They are ancient, ubiquitous, and indispensable players in the grand theater of life. From recycling nutrients in the deepest oceans to driving the very evolution of species, viruses are the unseen architects, constantly shaping and reshaping the world around us. Embracing this broader ecological perspective allows for a deeper appreciation of their complex and often beneficial roles, transforming our understanding of life on Earth.