The Unsung Heroes: Understanding the Diverse World of Herbivores

In the intricate tapestry of life, few roles are as fundamental and fascinating as that of the herbivore. These plant-eating organisms form the crucial link between the sun’s energy, captured by plants, and the rest of the animal kingdom. Without herbivores, the flow of energy through ecosystems would grind to a halt, profoundly impacting every creature from the smallest insect to the largest predator. Far from being simple eaters, herbivores exhibit an astonishing array of adaptations, behaviors, and ecological impacts that make them true architects of our natural world.

What Exactly is a Herbivore?

At its core, a herbivore is an animal that primarily consumes plants for its energy and nutrient needs. This definition, while straightforward, belies a world of incredible diversity. From microscopic zooplankton grazing on algae to colossal elephants browsing on trees, herbivores come in all shapes and sizes, each uniquely equipped to extract sustenance from the plant kingdom. They are the primary consumers in most food webs, converting plant matter into animal biomass, thereby making energy available to carnivores and omnivores.

Why Eat Plants? The Abundance of Green Energy

Plants are the ultimate producers, harnessing sunlight through photosynthesis to create organic compounds. This makes them the most abundant food source on Earth. However, plant material presents a unique challenge: it is often tough, fibrous, and contains complex carbohydrates like cellulose, which most animals cannot digest directly. This challenge has driven an incredible evolutionary arms race, leading to the specialized adaptations we see in herbivores today.

Digestive Strategies: From Teeth to Tummies

The primary hurdle for any herbivore is breaking down cellulose, the main structural component of plant cell walls. Animals lack the enzymes to do this themselves. Over millennia, herbivores have evolved remarkable strategies, often involving symbiotic relationships with microorganisms, to overcome this digestive barrier.

Dental Adaptations for a Plant-Based Diet

The first line of defense in plant digestion begins in the mouth. Herbivores typically possess specialized teeth designed for grinding and crushing tough plant material.

- Flat Molars: Unlike the sharp canines of carnivores, herbivores have broad, flat molars that act like millstones, efficiently pulverizing fibrous plants.

- Diastema: Many herbivores, such as horses and rabbits, have a gap between their incisors and molars, known as a diastema, which allows them to manipulate food more effectively with their tongues.

- Continuous Growth: Some herbivores, like rodents, have incisors that grow continuously to compensate for wear caused by gnawing on hard plant matter.

The Marvel of Digestive Systems

Beyond teeth, the internal digestive systems of herbivores are marvels of evolutionary engineering, broadly categorized into two main types:

Monogastric Herbivores (Hindgut Fermenters):

These herbivores have a single-chambered stomach, similar to humans, but possess an enlarged cecum and large intestine where microbial fermentation occurs. This process, known as hindgut fermentation, allows microbes to break down cellulose after the initial digestive processes in the stomach and small intestine.

- Examples: Horses, rabbits, koalas, rhinos.

- Efficiency: While effective, hindgut fermenters cannot re-digest the microbial protein produced, making their nutrient absorption slightly less efficient than foregut fermenters.

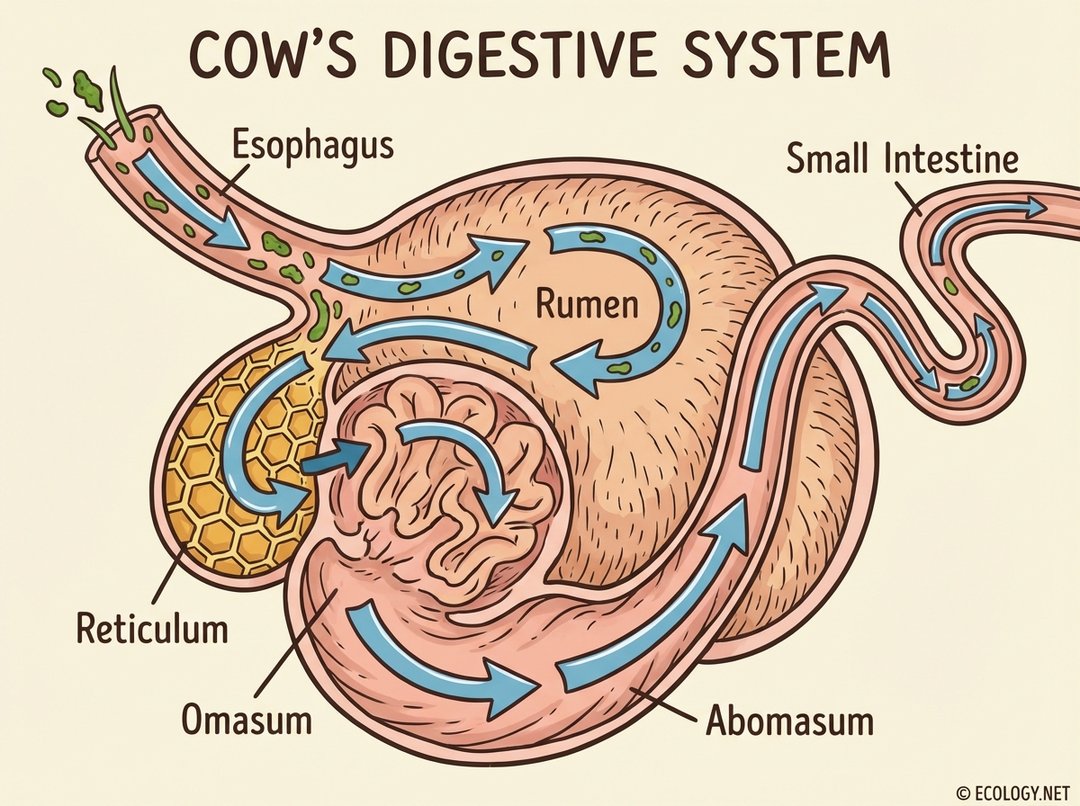

Ruminant Herbivores (Foregut Fermenters):

Perhaps the most famous example of digestive specialization, ruminants possess a multi-chambered stomach that acts as a sophisticated fermentation vat. This allows them to break down cellulose before the food reaches the true stomach.

The process involves four distinct chambers:

- Rumen: The largest chamber, where ingested plant material is mixed with saliva and teeming with microbes that begin cellulose digestion.

- Reticulum: Works with the rumen to sort food particles and form cud for regurgitation and re-chewing (rumination).

- Omasum: Absorbs water and filters out large particles.

- Abomasum: The “true stomach,” where digestive enzymes break down microbes and partially digested food.

This elaborate system allows ruminants to extract maximum nutrients from fibrous diets, even digesting the microbes themselves as a protein source.

The Power of Symbiosis: Gut Microbes

Central to both hindgut and foregut fermentation is the incredible partnership between herbivores and their gut microbiota. Billions of bacteria, fungi, and protozoa reside in specialized digestive chambers, producing enzymes that can break down cellulose into simpler compounds. In return, the herbivore provides a stable environment and a constant supply of food. This symbiotic relationship is a cornerstone of herbivore success, enabling them to thrive on diets that would be indigestible to most other animals.

Beyond Leaves: Diverse Herbivore Diets

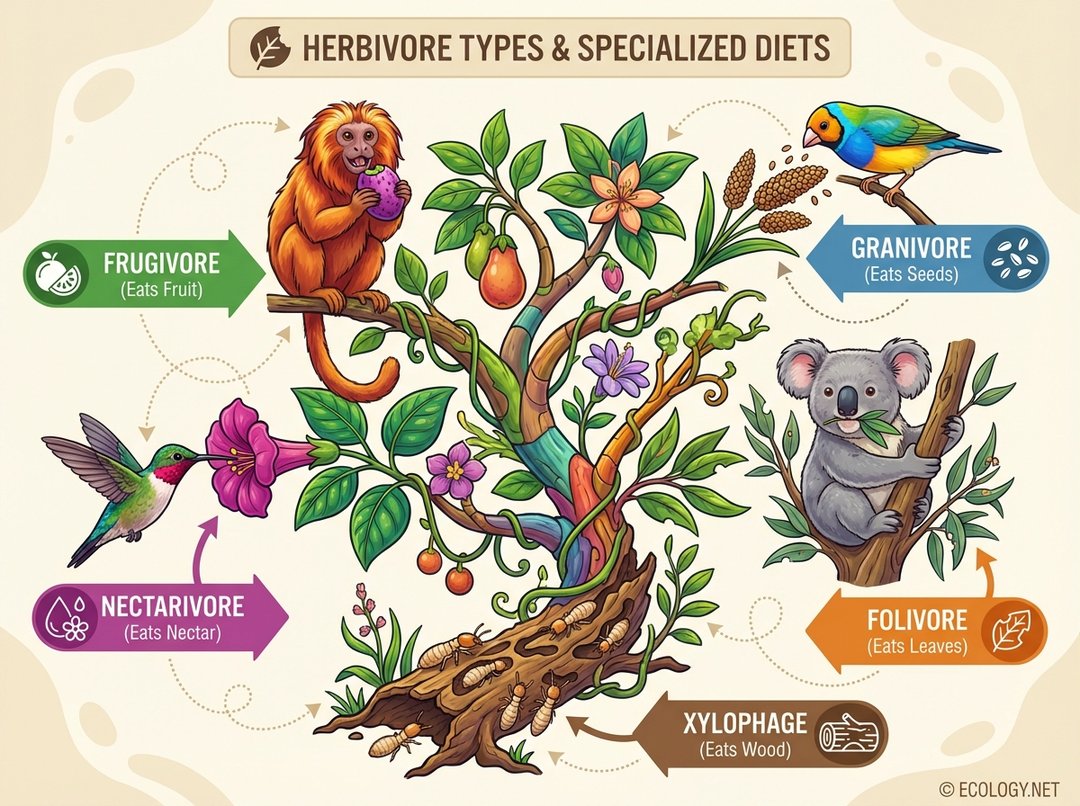

While many people envision herbivores simply munching on grass or leaves, their diets are incredibly diverse, leading to specialized classifications based on their preferred plant parts.

- Frugivores: These fruit eaters, like many monkeys, bats, and birds, play a vital role in seed dispersal, helping plants reproduce and colonize new areas.

- Granivores: Seed eaters, such as many rodents and birds, influence plant population dynamics by consuming seeds, which are often rich in nutrients.

- Nectarivores: Animals like hummingbirds, bees, and some bats feed on nectar, a sugary liquid produced by flowers. In doing so, they often act as crucial pollinators, facilitating plant reproduction.

- Folivores: Leaf eaters, including koalas, sloths, and many insect larvae, face the challenge of digesting tough, low-nutrient leaves, often requiring highly specialized digestive systems.

- Xylophages: Wood eaters, such as termites and certain beetle larvae, are essential decomposers, breaking down dead wood and returning nutrients to the ecosystem.

- Grazers: Primarily consume grasses (e.g., cattle, zebras).

- Browsers: Feed on leaves, twigs, and bark from shrubs and trees (e.g., deer, giraffes).

The Coevolutionary Arms Race: Plants vs. Herbivores

The relationship between plants and herbivores is not always a peaceful one. Plants have evolved an astonishing array of defenses to protect themselves from being eaten, leading to a fascinating “arms race” with herbivores constantly developing counter-adaptations.

Plant Defenses

- Physical Defenses:

- Thorns and Spines: Sharp structures deter larger herbivores.

- Tough Leaves and Waxes: Make leaves difficult to chew and digest.

- Trichomes: Hairy structures on leaves that can trap or irritate small insects.

- Chemical Defenses:

- Toxins: Compounds like alkaloids (e.g., nicotine, caffeine) and cyanogenic glycosides can be poisonous.

- Deterrents: Tannins make plant tissues unpalatable or indigestible. Terpenes can be bitter or aromatic.

- Indirect Defenses: Some plants release volatile chemicals when damaged, attracting predators of the herbivores that are eating them.

Herbivore Adaptations

In response to plant defenses, herbivores have developed equally ingenious strategies:

- Behavioral Adaptations:

- Selective Feeding: Eating only specific parts of a plant, or avoiding highly toxic plants altogether.

- Timing: Feeding on younger leaves that may have fewer defenses.

- Detoxification: Some animals consume clay or charcoal to bind toxins in their gut.

- Physiological Adaptations:

- Detoxification Enzymes: Specialized enzymes in the liver or gut to break down plant toxins.

- Toxin Sequestration: Some herbivores absorb and store plant toxins, using them for their own defense against predators.

- Morphological Adaptations:

- Specialized Mouthparts: Insects may have piercing-sucking mouthparts to bypass tough outer layers, or mandibles adapted to specific plant textures.

A classic example of this coevolutionary dance is the relationship between the monarch butterfly caterpillar and the milkweed plant.

Milkweed plants produce cardiac glycosides, potent toxins that are harmful to most animals. However, monarch caterpillars have evolved the ability to not only tolerate these toxins but to sequester them within their own bodies. This makes the caterpillars, and later the adult butterflies, poisonous to predators, providing them with a powerful defense mechanism. This intricate interaction showcases how plants drive herbivore evolution, and vice versa.

The Ecological Importance of Herbivores

The role of herbivores extends far beyond simply eating plants. They are indispensable engineers of ecosystems, influencing everything from nutrient cycling to landscape structure.

- Energy Flow: As primary consumers, herbivores are the vital conduit for energy transfer from producers (plants) to higher trophic levels (carnivores and omnivores). Without them, the energy stored in plants would largely remain inaccessible to most animal life.

- Shaping Landscapes: Grazing and browsing herbivores can dramatically alter plant communities. They can prevent forests from encroaching on grasslands, maintain open savannas, and influence the distribution and abundance of various plant species.

- Nutrient Cycling: By consuming plant matter, herbivores break it down and return nutrients to the soil through their waste products, accelerating decomposition and nutrient availability for plants.

- Seed Dispersal and Pollination: Frugivores and nectarivores are crucial partners in plant reproduction, dispersing seeds far from the parent plant and facilitating cross-pollination.

- Impact on Biodiversity: Selective grazing can sometimes increase plant diversity by preventing dominant species from outcompeting others. Conversely, overgrazing can lead to desertification and loss of biodiversity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Plant Eaters

From the smallest aphid to the largest elephant, herbivores are a testament to life’s incredible adaptability and interconnectedness. Their specialized diets, complex digestive systems, and ongoing evolutionary dance with plants highlight their critical role in maintaining ecological balance. They are not merely consumers but active participants in shaping the very fabric of our planet’s ecosystems. Understanding herbivores is key to appreciating the delicate yet resilient nature of life on Earth and recognizing the profound impact these unsung heroes have on every corner of the natural world.