Unveiling Monoculture: The Hidden Costs of Agricultural Uniformity

Imagine a vast expanse of land, stretching as far as the eye can see, covered by a single type of plant. Perhaps it is a sea of golden wheat swaying in the breeze, or endless rows of corn standing tall under the sun. This seemingly efficient approach to farming is known as monoculture, a dominant practice in modern agriculture that involves growing a single crop species repeatedly on the same land. While it offers certain immediate advantages, its long-term ecological and environmental consequences are profound and far-reaching, shaping the very fabric of our planet’s ecosystems.

What Exactly is Monoculture?

At its core, monoculture is the cultivation of a single crop species in a given area. This practice contrasts sharply with the natural world’s inherent biodiversity, where a multitude of plant and animal species coexist and interact. Think of a natural forest or a vibrant meadow, teeming with diverse life forms. Monoculture, by design, simplifies this complexity, focusing on maximizing the yield of one specific crop.

Common examples of monoculture are ubiquitous in our food system. Large-scale farms often specialize in single crops like corn, soybeans, wheat, rice, potatoes, or even fruit trees such as oranges and bananas. This specialization allows for highly mechanized farming practices, from planting to harvesting, which can reduce labor costs and increase production efficiency.

However, this efficiency comes at a significant ecological price. To truly understand monoculture, it is essential to visualize its stark contrast with a biodiverse agricultural landscape.

The image above directly illustrates the core concept of monoculture by contrasting it with a biodiverse ecosystem, making the fundamental difference clear. On one side, a single crop dominates, creating a uniform environment. On the other, a rich tapestry of different plants thrives, supporting a wider array of life.

The Allure of Monoculture: Why is it So Widespread?

Given its ecological drawbacks, one might wonder why monoculture became the prevailing agricultural model. The reasons are primarily economic and logistical:

- Economic Efficiency: Growing a single crop allows farmers to specialize their equipment, labor, and knowledge. Large machinery can be used across vast fields, reducing the need for varied tools and manual labor.

- Simplified Management: Managing one crop is often simpler than managing many. Fertilization, pest control, and harvesting schedules can be standardized, streamlining operations.

- Predictable Yields: With specialized inputs and controlled environments, monoculture can offer more predictable yields, which is attractive to large agricultural corporations and commodity markets.

- Market Demands: Global food markets often demand large quantities of specific staple crops, incentivizing farmers to produce these crops on a massive scale.

The Ecological Ripple Effect: Consequences of Monoculture

While monoculture offers short-term economic benefits, its long-term ecological consequences are a growing concern for environmental scientists and sustainable agriculture advocates.

Loss of Biodiversity

Perhaps the most direct impact of monoculture is the drastic reduction in biodiversity. When a single crop dominates an area, it displaces native plants and animals that once inhabited the ecosystem. This leads to:

- Habitat Destruction: Vast fields of a single crop offer little habitat diversity for insects, birds, and other wildlife.

- Reduced Genetic Diversity: Often, monoculture relies on a few genetically identical crop varieties, making the entire crop vulnerable to specific pests or diseases.

- Disruption of Food Webs: The absence of diverse plant life impacts the entire food web, from pollinators to predators, leading to ecological imbalance.

Soil Degradation

Healthy soil is the foundation of productive agriculture, yet monoculture often depletes soil health:

- Nutrient Depletion: Each crop has specific nutrient requirements. Growing the same crop repeatedly extracts the same nutrients from the soil year after year, leading to depletion unless heavily supplemented with synthetic fertilizers.

- Erosion: Uniform fields with limited ground cover can be more susceptible to wind and water erosion, especially after harvest.

- Reduced Soil Structure: Heavy machinery used in monoculture can compact the soil, reducing its ability to absorb water and support beneficial microbial life.

Pest and Disease Outbreaks

One of the most critical vulnerabilities of monoculture is its susceptibility to widespread pest infestations and disease outbreaks. In a biodiverse ecosystem, natural predators and a variety of plant defenses help keep pest populations in check. In a monoculture:

- Lack of Natural Enemies: Without diverse habitats, beneficial insects and predators that control pests are often absent.

- Rapid Spread: A genetically uniform crop provides an ideal environment for pests and diseases to spread rapidly, as there are no barriers or resistant varieties to slow their progress.

This image visually represents the ‘Pest and Disease Outbreaks’ consequence of monoculture, providing a concrete, impactful example of the ecological vulnerability described. A single pest or pathogen can devastate an entire harvest, leading to significant economic losses and food security concerns.

Increased Chemical Use

To combat the inevitable pest and disease problems, and to compensate for depleted soil nutrients, monoculture often necessitates a heavy reliance on synthetic chemicals:

- Pesticides and Herbicides: These chemicals are used to control pests and weeds that thrive in uniform crop environments.

- Synthetic Fertilizers: Applied to replenish nutrients lost from continuous cropping.

The overuse of these chemicals can lead to water pollution, harm non-target species, and contribute to the development of pesticide-resistant pests, creating a vicious cycle.

Water Scarcity and Pollution

Monoculture can also exacerbate water issues. Large-scale irrigation for thirsty single crops can deplete local water sources. Runoff from fields laden with fertilizers and pesticides can contaminate rivers, lakes, and groundwater, impacting aquatic ecosystems and human health.

Beyond the Field: Broader Societal and Economic Impacts

The effects of monoculture extend beyond the immediate environment, influencing society and the economy:

- Food Security Concerns: Over-reliance on a few staple crops makes global food systems vulnerable to crop failures caused by climate change, pests, or diseases. Diversifying agricultural production is crucial for long-term food security.

- Economic Vulnerability for Farmers: Farmers specializing in a single crop face significant economic risks if that crop fails or market prices fluctuate dramatically.

- Impact on Local Communities: The industrial scale of monoculture often favors large corporations over small family farms, impacting rural economies and traditional farming practices.

Towards a More Sustainable Future: Alternatives to Monoculture

Recognizing the challenges posed by monoculture, ecologists and agricultural scientists are championing alternative farming practices that promote biodiversity and ecological resilience. These methods aim to work with nature, rather than against it.

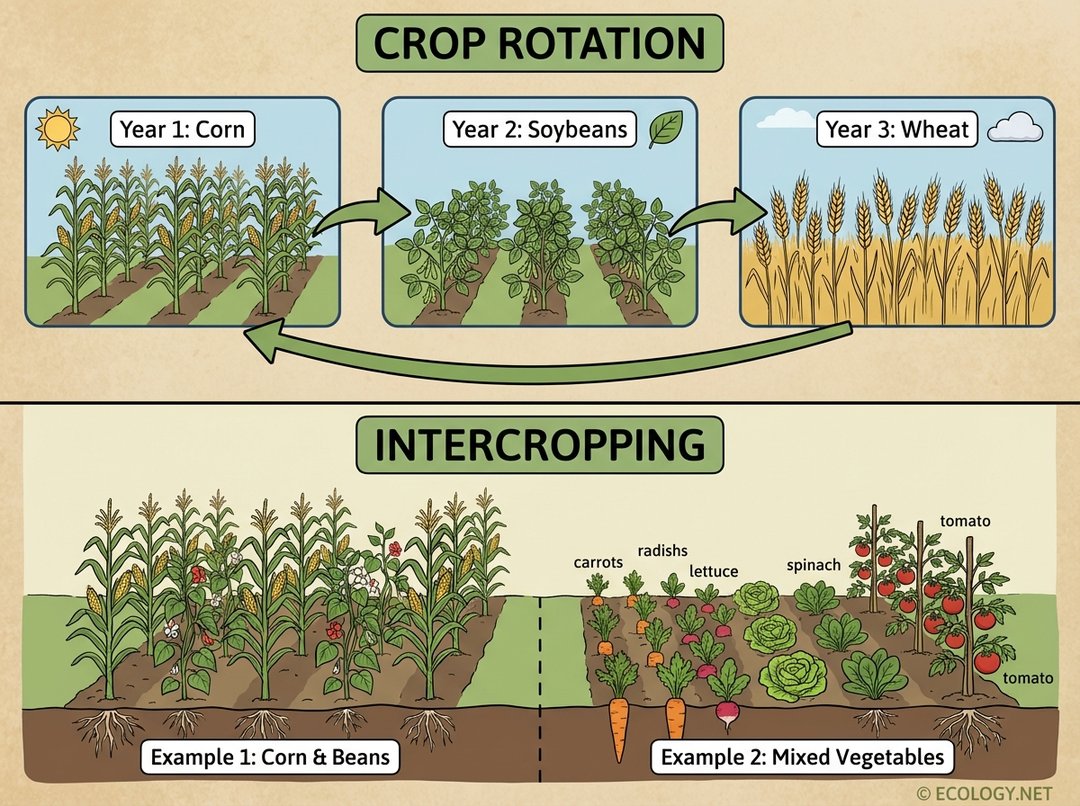

Crop Rotation

Instead of planting the same crop year after year, crop rotation involves systematically varying the crops grown in a particular field over several seasons. This practice offers numerous benefits:

- Nutrient Cycling: Different crops have different nutrient needs and can even replenish soil nutrients. For example, legumes (like soybeans) fix nitrogen in the soil, benefiting subsequent crops.

- Pest and Disease Management: Breaking the life cycle of pests and diseases specific to one crop by planting a different crop can significantly reduce their populations without heavy chemical use.

- Improved Soil Structure: Rotating crops with different root systems can improve soil aeration and structure.

Intercropping and Polyculture

Intercropping involves growing two or more crops in close proximity in the same field. Polyculture is a broader term for farming systems that cultivate multiple crops simultaneously. These practices mimic natural ecosystems and offer synergistic benefits:

- Increased Biodiversity: A greater variety of plants supports a wider range of beneficial insects and microorganisms.

- Pest Deterrence: Certain plants can act as natural deterrents to pests of neighboring crops.

- Resource Utilization: Different crops can utilize resources like sunlight, water, and nutrients more efficiently by occupying different niches. For instance, tall corn can provide a trellis for climbing beans, which in turn fix nitrogen for the corn.

This image illustrates practical solutions and alternatives to monoculture, such as crop rotation and intercropping, directly supporting the ‘Towards a More Sustainable Future’ section and offering a positive vision. These methods are not just theoretical; they are being successfully implemented by farmers worldwide.

Other Sustainable Practices

- Agroforestry: Integrating trees and shrubs into agricultural landscapes, providing shade, windbreaks, and additional products while enhancing biodiversity.

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM): A holistic approach that combines biological, cultural, physical, and chemical tools to manage pests in a way that minimizes economic, health, and environmental risks.

- Organic Farming Principles: Emphasizing soil health, biodiversity, and natural processes, avoiding synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

Conclusion

Monoculture, while a cornerstone of industrial agriculture for decades, presents a complex challenge to our planet’s ecological health and long-term food security. Its efficiency in producing vast quantities of single crops comes at the cost of biodiversity loss, soil degradation, increased vulnerability to pests and diseases, and heavy reliance on chemical inputs.

Understanding monoculture is the first step towards appreciating the urgent need for more sustainable agricultural practices. By embracing methods like crop rotation, intercropping, and agroforestry, we can foster resilient ecosystems, protect our natural resources, and build a more secure and diverse food future. The shift away from agricultural uniformity towards ecological diversity is not merely an environmental ideal; it is an essential pathway to a healthier planet and more sustainable human societies.