In the intricate tapestry of life, there exists a hidden, tireless force that ensures the continuity of existence. While we often marvel at the vibrant growth of plants and the dynamic lives of animals, an equally vital process unfolds beneath our feet and within the quiet corners of nature: decomposition. Far from being merely the end of life, decomposition is a powerful beginning, a fundamental ecological process that recycles the building blocks of life, making them available for new generations.

Imagine a world without decomposition. Dead leaves would pile up endlessly, fallen trees would remain intact for centuries, and the nutrients locked within deceased organisms would be permanently sequestered. Life as we know it would grind to a halt. Decomposition is the ultimate recycling program, a biological imperative that transforms dead organic matter into simpler substances, enriching the soil and fueling the growth of new life. It is a process driven by an astonishing diversity of organisms, each playing a crucial role in nature’s grand cleanup.

The Unsung Heroes: Who’s Involved in Decomposition?

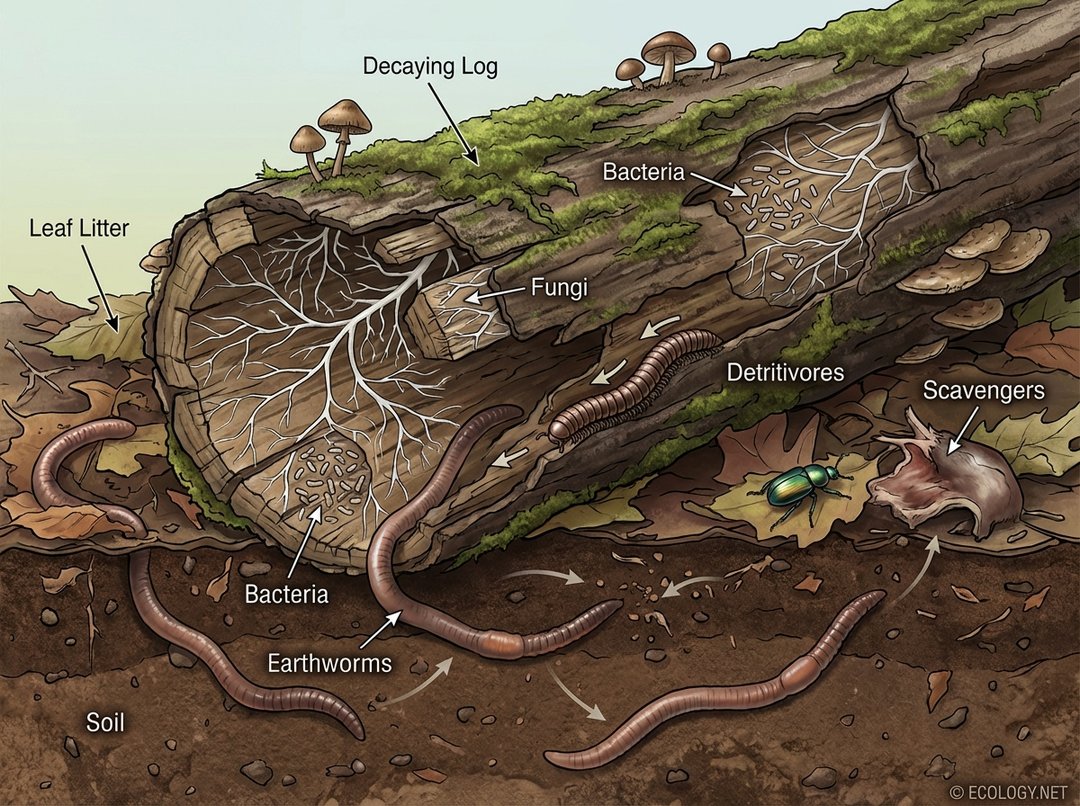

Decomposition is not a solitary act but a collaborative effort involving a vast array of organisms, often referred to collectively as decomposers. These unsung heroes come in many forms, from the microscopic to the macroscopic, working in concert to break down organic material.

The Microscopic Maestros: Bacteria and Fungi

These are the primary decomposers, the true workhorses of the process. They are responsible for the vast majority of chemical breakdown.

- Bacteria: Ubiquitous in every environment, bacteria are incredibly diverse. Some specialize in breaking down specific compounds like cellulose or lignin, while others thrive on simpler sugars. They release enzymes that chemically digest organic matter, absorbing the resulting nutrients and releasing inorganic compounds back into the environment.

- Fungi: From the visible mushrooms sprouting from decaying logs to the vast networks of mycelium threading through soil, fungi are master decomposers. Their hyphae, thread-like structures, penetrate organic matter, secreting powerful enzymes that break down complex molecules. Fungi are particularly adept at degrading tough materials like wood, which many bacteria struggle with.

The Macroscopic Movers: Detritivores and Scavengers

While bacteria and fungi handle the chemical breakdown, detritivores and scavengers perform the crucial physical breakdown, fragmenting larger pieces of organic matter into smaller ones, making them more accessible to microbial action.

- Detritivores: These organisms directly consume dead organic matter, known as detritus. By doing so, they physically break it into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for microbial colonization. Examples include:

- Earthworms: Famous for their soil-churning activities, earthworms ingest soil and detritus, digesting organic matter and excreting nutrient-rich castings. Their burrowing also aerates the soil, benefiting other decomposers.

- Millipedes: Often found in leaf litter, millipedes chew and fragment decaying plant material.

- Springtails and Mites: Tiny but numerous, these arthropods graze on fungi and detritus, further breaking down organic particles.

- Woodlice (Pill Bugs/Sow Bugs): These crustaceans feed on decaying plant material, especially in damp environments.

- Scavengers: These animals consume dead animals. While not directly breaking down organic matter into its simplest forms, they remove large carcasses, preventing the buildup of dead bodies and accelerating the initial stages of decomposition. Examples include:

- Beetles: Carrion beetles and dung beetles play vital roles in breaking down animal remains and waste.

- Vultures and Crows: Larger scavengers that consume animal carcasses, preventing the spread of disease and returning nutrients to the food web.

The Grand Transformation: A Step-by-Step Breakdown

Decomposition is not an instantaneous event but a gradual process that unfolds in distinct stages, particularly evident when observing the breakdown of an animal carcass. This sequential transformation highlights the coordinated efforts of various decomposers over time.

Decomposition of an Animal Carcass: A Case Study

- Fresh Stage: Immediately after death, the body appears intact. Internal bacteria begin to break down tissues from within. Scavengers, such as blowflies, are often the first external visitors, laying eggs on the carcass.

- Bloat Stage: As anaerobic bacteria multiply, they produce gases (like methane, hydrogen sulfide, and carbon dioxide) within the body, causing it to swell and emit a strong odor. Maggots (fly larvae) hatch and begin feeding, initiating significant tissue consumption.

- Active Decay Stage: The carcass deflates as gases escape and tissues liquefy. Maggot activity is at its peak, consuming most of the soft tissues. Other detritivores, like beetles, join the feast. The strong odor persists, attracting more insects and microbes.

- Advanced Decay Stage: Most of the flesh is gone, leaving behind bones, cartilage, hair, and some resistant tissues. Maggot activity decreases significantly. Fungi and bacteria continue to break down remaining soft tissues and begin to colonize the bones.

- Dry Remains Stage: Only bones, hair, and a few dried fragments remain. The decomposition rate slows considerably. These resistant materials will eventually break down over a much longer period, blending into the soil.

While the decomposition of an animal carcass is dramatic and easily observed, plant decomposition follows similar principles, albeit often at a slower pace and with less visible stages. Fallen leaves, branches, and dead roots are gradually broken down by fungi, bacteria, and detritivores, returning their organic components to the soil.

Why Decomposition Matters: The Engine of Life

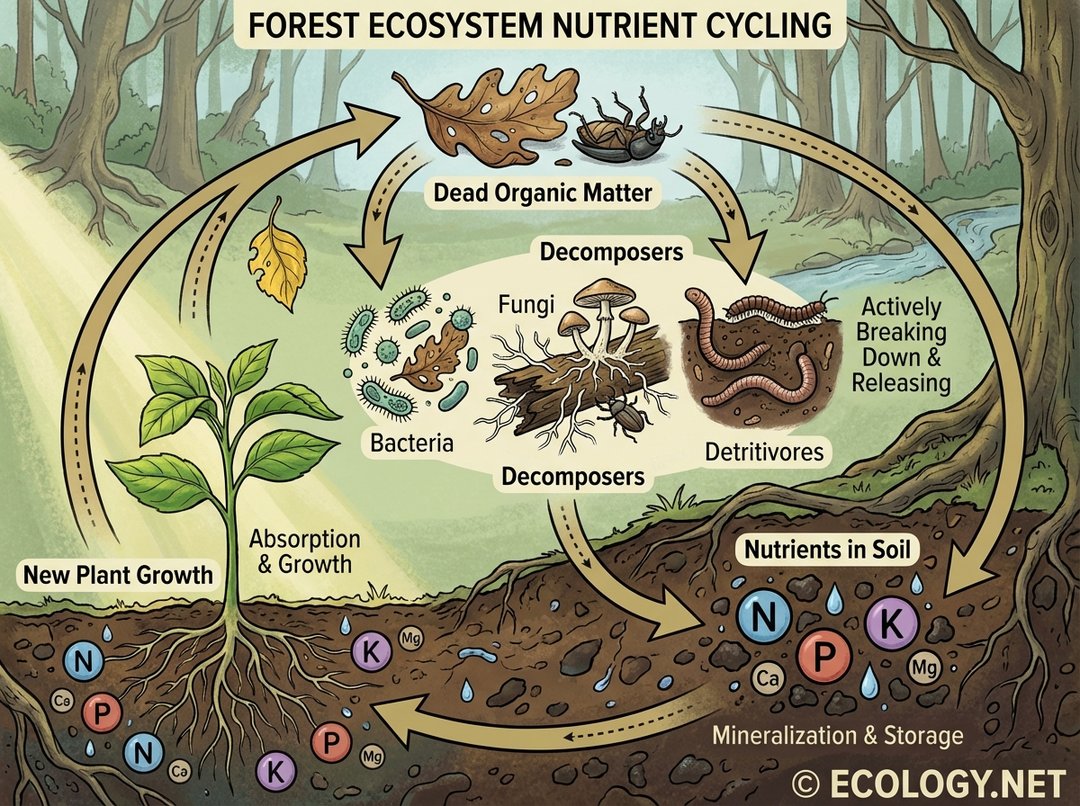

Beyond the fascinating biological processes, decomposition is an indispensable ecological service. It is the engine that drives nutrient cycling, making life on Earth possible.

Nutrient Cycling: The Ultimate Recycling Program

Every living organism contains essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, along with carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen. When an organism dies, these nutrients are locked within its tissues. Decomposition is the process that unlocks them. Decomposers break down complex organic molecules into simpler inorganic forms, a process called mineralization. These inorganic nutrients are then released into the soil or water, becoming available for uptake by plants, which form the base of most food webs. This continuous loop, from living organisms to dead organic matter, to decomposers, to available nutrients, and back to living organisms, is known as nutrient cycling. Without it, ecosystems would quickly run out of essential elements, and life would cease.

Soil Health and Structure

Decomposition is fundamental to creating healthy, fertile soil. As organic matter breaks down, it forms humus, a stable, dark material that improves soil structure, water retention, and aeration. Humus acts like a sponge, holding onto water and nutrients, making them available to plant roots. It also provides a habitat for countless soil organisms, further enhancing soil biodiversity and productivity.

Carbon Sequestration

Decomposition plays a critical role in the global carbon cycle. While some carbon is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide during decomposition (respiration by decomposers), a significant portion is incorporated into the soil as organic matter. This soil organic carbon is a vital reservoir, helping to regulate atmospheric carbon levels and mitigate climate change. Healthy soils with abundant organic matter are effective carbon sinks.

Factors Influencing Decomposition Rates

The speed at which decomposition occurs is not constant; it varies greatly depending on several environmental and biological factors. Understanding these factors helps explain why a fallen leaf might disappear in months, while a log could take decades.

Environmental Conditions

- Temperature: Generally, warmer temperatures accelerate decomposition because microbial activity increases with heat. However, extremely high temperatures can inhibit some decomposers. Freezing temperatures halt decomposition almost entirely.

- Moisture: Decomposers require water to thrive. Optimal moisture levels promote rapid decomposition. Too little water (deserts) or too much water (waterlogged soils, bogs) can slow the process significantly. In anaerobic (oxygen-deprived) conditions, decomposition is much slower and often leads to the accumulation of organic matter, like peat.

- Oxygen Availability: Most efficient decomposition is aerobic, requiring oxygen for decomposers to respire. Anaerobic decomposition, which occurs in waterlogged soils or deep within large organic masses, is much slower and produces different byproducts, such as methane.

Quality of the Organic Matter (Substrate Quality)

- Chemical Composition:

- Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C:N) Ratio: Materials with a low C:N ratio (e.g., fresh green leaves, animal waste) decompose quickly because nitrogen is readily available for microbial growth. Materials with a high C:N ratio (e.g., wood, straw) decompose slowly as decomposers must work harder to find enough nitrogen.

- Lignin Content: Lignin is a complex, tough polymer found in plant cell walls, especially wood. It is highly resistant to decomposition, making woody materials break down very slowly.

- Presence of Toxins: Some plants produce secondary compounds that can inhibit microbial activity, slowing decomposition.

- Physical Structure: Smaller pieces of organic matter decompose faster due to a larger surface area available for microbial colonization and enzymatic action. This is why detritivores are so important.

Decomposer Community

The diversity and abundance of decomposers in an ecosystem also influence decomposition rates. A rich community of bacteria, fungi, and detritivores working together can break down a wider range of organic materials more efficiently than a limited community.

Decomposition in Diverse Environments

The principles of decomposition remain constant, but its manifestation varies across different ecosystems, shaped by the unique environmental conditions and decomposer communities present.

- Forest Ecosystems: Characterized by abundant leaf litter and woody debris, forests are prime examples of active decomposition. Fungi are particularly dominant in breaking down lignin-rich wood, while a diverse array of detritivores processes leaf litter. The resulting humus is crucial for forest soil fertility.

- Aquatic Ecosystems (Lakes, Rivers, Oceans): Decomposition occurs both in the water column and in sediments. In oxygen-rich waters, aerobic bacteria and fungi break down dead algae and aquatic plants. In deeper, oxygen-poor sediments, anaerobic decomposition dominates, often leading to the accumulation of organic matter and the release of gases like methane.

- Deserts: Decomposition rates are generally very slow in deserts due to extreme dryness and temperature fluctuations. Organic matter can persist for long periods, and specialized decomposers adapted to arid conditions are at work.

- Human Environments (Composting): Composting is a controlled form of decomposition, where humans intentionally create optimal conditions (moisture, aeration, C:N ratio) to accelerate the breakdown of organic waste. This process harnesses the power of natural decomposers to create nutrient-rich compost for gardens and agriculture.

The next time you walk through a forest or observe a garden, remember the silent, ceaseless work happening beneath the surface. Decomposition is not merely decay; it is the vital process of renewal, a testament to nature’s efficiency and interconnectedness.

Conclusion: The Endless Cycle of Life

Decomposition is a cornerstone of life on Earth, a process so fundamental yet often overlooked. It is the ultimate act of recycling, transforming death into life and ensuring the continuous flow of energy and nutrients through ecosystems. From the microscopic bacteria and fungi to the visible earthworms and beetles, a vast and diverse crew of decomposers works tirelessly to maintain the delicate balance of our planet.

Understanding decomposition not only deepens our appreciation for the natural world but also highlights the importance of healthy soil, biodiversity, and sustainable practices. It reminds us that nothing truly disappears in nature; everything is transformed, contributing to the endless, beautiful cycle of life and renewal.