Unveiling Watersheds: The Hidden Architects of Our Water World

Imagine a single drop of rain falling onto a mountain peak. Where does it go? Does it trickle down one side, joining a small stream that eventually feeds a mighty river, or does it flow down the other, embarking on an entirely different journey? The answer lies in the fascinating concept of a watershed, an invisible boundary that dictates the destiny of every raindrop, every snowflake, and every ounce of water on our planet.

Watersheds are far more than just geographical areas; they are intricate, interconnected systems that shape our landscapes, sustain our ecosystems, and provide the very water we drink. Understanding them is key to appreciating the delicate balance of nature and our role in its preservation.

What is a Watershed? The Land That Feeds Our Waters

At its core, a watershed, also known as a drainage basin, is simply an area of land where all precipitation, whether from rain or snow, drains to a common outlet. This outlet could be a stream, a river, a lake, or even an ocean. Think of it like a giant funnel, collecting water from a vast expanse of land and directing it towards a single point.

The boundaries of a watershed are defined by the highest points of land, such as mountain ridges or hills. These elevated areas, often called “divides,” act as natural barriers, separating one drainage basin from another. Water falling on one side of a divide will flow into one watershed, while water falling on the other side will enter a different one.

Every stream, every river, and every lake has its own watershed. From the smallest trickles in your backyard to the colossal Amazon River basin, the principle remains the same: water flows downhill, guided by topography, until it reaches its common destination.

Scale Matters: From Puddles to Continents

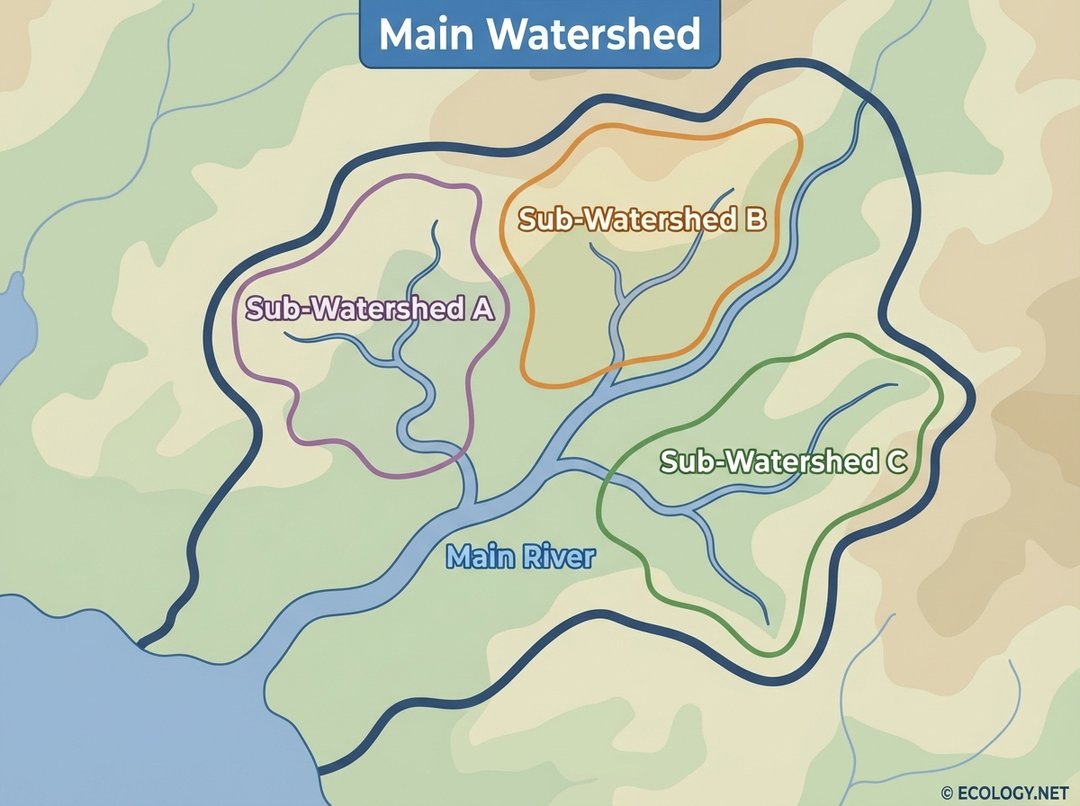

One of the most intriguing aspects of watersheds is their hierarchical nature. They exist at every conceivable scale, from tiny areas draining into a roadside ditch to immense basins encompassing entire continents. A small stream’s watershed might only cover a few acres, but that stream is likely a tributary to a larger river, which in turn has its own, much larger watershed. This larger river might then flow into an even grander river system, eventually reaching a major bay or ocean.

Consider a small creek flowing through a local park. The land that drains into that creek forms its immediate watershed. This creek then flows into a larger river, which has its own, broader watershed encompassing many smaller creeks and streams. This river might then join an even larger river, like the Mississippi, whose watershed stretches across a significant portion of North America. This nesting doll effect means that actions taken in a small, upstream watershed can have ripple effects far downstream, impacting water quality and ecosystems in much larger basins.

The Living Landscape: Components and Influences within a Watershed

A watershed is not just about water and land; it is a vibrant, dynamic ecosystem composed of countless interacting elements. The type of land cover within a watershed profoundly influences how water moves through it, how clean it remains, and what life it can support.

- Forests: Densely forested areas act like natural sponges. Tree canopies intercept rainfall, reducing the impact on the ground, while their roots stabilize soil, preventing erosion. The forest floor, rich in organic matter, absorbs vast amounts of water, slowly releasing it into streams and groundwater, helping to maintain consistent flows and filter pollutants.

- Agricultural Land: Farms and cultivated fields are common features in many watersheds. While essential for food production, agricultural practices can significantly impact water quality. Runoff from fields can carry fertilizers, pesticides, and sediment into waterways, leading to nutrient pollution and habitat degradation.

- Urban Areas: Cities and towns introduce impervious surfaces like roads, buildings, and parking lots. These surfaces prevent rainwater from soaking into the ground, leading to rapid runoff, increased flood risk, and the transport of pollutants like oil, chemicals, and litter directly into streams and rivers.

- Wetlands: Marshes, swamps, and bogs are critical components of many watersheds. They act as natural filters, removing pollutants from water, and as natural sponges, absorbing excess water during floods and releasing it during dry periods. Wetlands also provide vital habitats for a diverse array of plant and animal species.

- Rivers and Streams: These are the arteries of a watershed, transporting water, nutrients, and sediment. The health of these waterways is a direct reflection of the health of the entire watershed.

All these components are intricately linked. A change in one part of the watershed, such as deforestation on a hillside or the construction of a new development, can have cascading effects throughout the entire system, altering water flow, quality, and the health of its inhabitants.

Why Watersheds Matter: More Than Just Water Flow

The significance of watersheds extends far beyond simply directing water. They are fundamental to nearly every aspect of life and the environment.

- Water Supply: Our drinking water, whether sourced from surface water or groundwater, originates within a watershed. The quality of the water we consume is directly tied to the health and management of its source watershed.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: Watersheds encompass a vast array of habitats, from mountain forests to riparian zones along rivers and coastal estuaries. They support an incredible diversity of plant and animal life, including many endangered species. Healthy watersheds are crucial for maintaining ecological balance.

- Flood Control: Natural features within a healthy watershed, such as forests, wetlands, and floodplains, absorb and slow down floodwaters, reducing the risk of damage to communities downstream. Degradation of these features can exacerbate flooding.

- Recreation and Economy: Rivers, lakes, and coastal areas within watersheds provide countless opportunities for recreation, including fishing, boating, swimming, and hiking. These activities often support local economies through tourism and related industries.

- Climate Regulation: Forests and wetlands within watersheds play a role in regulating local and regional climates by influencing temperature, humidity, and carbon sequestration.

Human Impact on Watersheds: A Delicate Balance

Humans are an integral part of most watersheds, and our activities inevitably leave a footprint. While we rely on watersheds for our survival, many human actions can significantly degrade their health.

- Pollution: This is perhaps the most pervasive threat.

- Non-point source pollution: This comes from diffuse sources, like agricultural runoff carrying fertilizers and pesticides, urban stormwater runoff laden with oil, chemicals, and litter, or sediment from construction sites. It is challenging to trace and manage.

- Point source pollution: This originates from a single, identifiable source, such as industrial discharge pipes or wastewater treatment plants. While often regulated, accidental releases can still occur.

- Land Use Change: Deforestation for agriculture or development removes vital vegetation that stabilizes soil and filters water. Urbanization replaces permeable surfaces with impervious ones, increasing runoff and reducing groundwater recharge.

- Habitat Alteration: Dam construction, channelization of rivers, and wetland drainage can drastically alter natural water flow, destroy critical habitats, and disrupt the life cycles of aquatic species.

- Water Extraction: Over-extraction of water for irrigation, industry, or municipal use can deplete rivers and aquifers, leading to reduced flows, dry streambeds, and impacts on downstream ecosystems and communities.

The cumulative effect of these impacts can lead to reduced water quality, increased flooding, loss of biodiversity, and diminished ecosystem services, ultimately affecting human well-being.

Protecting Our Watersheds: Collective Responsibility

Given their immense importance, protecting and restoring watersheds is a critical endeavor. It requires a holistic approach, recognizing that every action within a watershed has consequences for the entire system.

- Sustainable Land Management: Implementing practices that minimize erosion, reduce chemical runoff, and preserve natural vegetation is crucial. This includes sustainable forestry, conservation tillage in agriculture, and green infrastructure in urban planning.

- Pollution Reduction: Strict regulations on industrial discharges, improved wastewater treatment, and public education campaigns to reduce non-point source pollution are vital. Simple actions like properly disposing of hazardous waste and reducing fertilizer use in residential areas contribute significantly.

- Restoration Efforts: Restoring degraded wetlands, reforesting riparian zones, and removing obsolete dams can help bring watersheds back to health, enhancing their natural filtering and flood control capacities.

- Community Engagement: Local communities play a pivotal role in watershed protection. Citizen science initiatives, volunteer cleanups, and advocacy for sound environmental policies empower individuals to become stewards of their local waterways.

- Integrated Watershed Management: This approach considers the entire watershed as a single planning unit, involving all stakeholders, from farmers to urban planners to conservationists, in making decisions that balance human needs with ecological health.

Conclusion: Our Shared Water Future

Watersheds are the fundamental units of our water world, silently orchestrating the flow of life-giving water across our landscapes. They are complex, interconnected systems that provide essential services, from clean drinking water to diverse habitats and flood protection. Every ridge, every valley, every stream, and every human activity within these boundaries contributes to their overall health.

Understanding watersheds is not just an academic exercise; it is a call to action. By recognizing our place within these natural systems and embracing responsible stewardship, we can ensure that these vital arteries of our planet continue to thrive, providing clean water and healthy ecosystems for generations to come. The future of our water, and indeed our world, depends on it.