The Endless Journey: Unraveling the Wonders of the Water Cycle

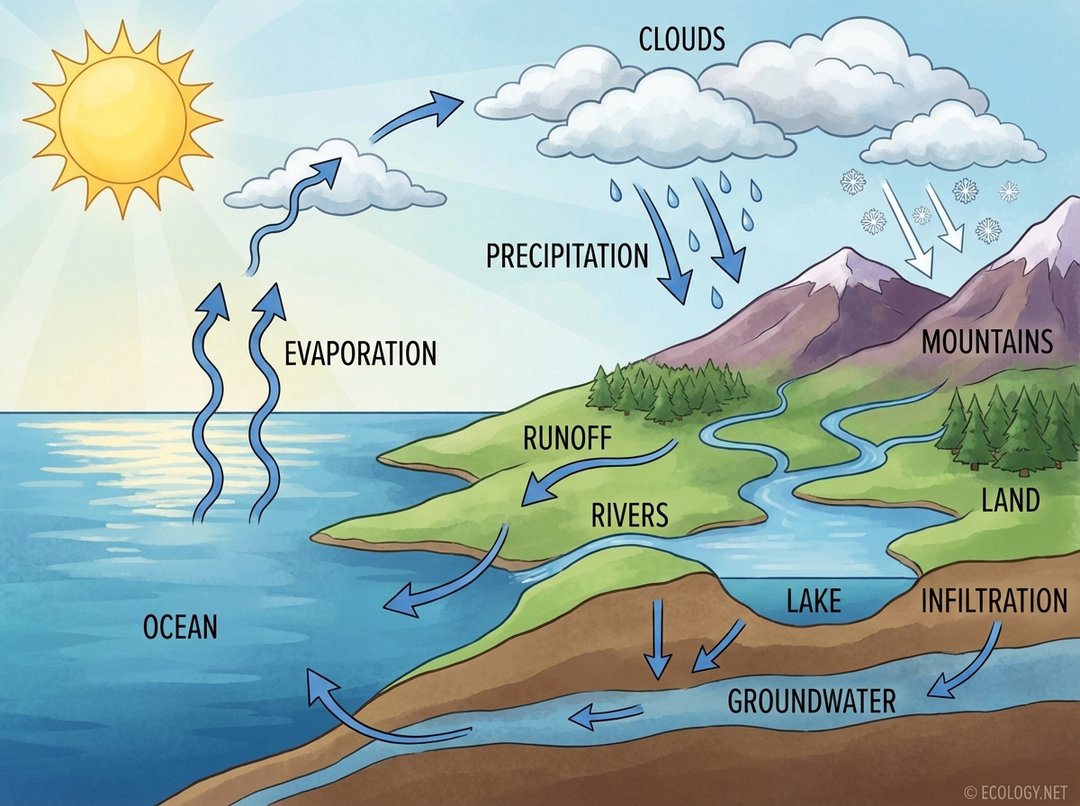

Water, the very essence of life, is constantly on the move. From the vast oceans to the highest clouds, and deep beneath our feet, it embarks on an incredible, never-ending journey known as the water cycle, or hydrological cycle. This fundamental process dictates weather patterns, shapes landscapes, and sustains every living organism on Earth. Understanding its intricate dance is key to appreciating our planet’s delicate balance.

The Core Stages: A Continuous Loop

The water cycle is a grand, interconnected system, but it can be broken down into several key stages. Think of it as a global conveyor belt for water, powered by the sun.

Evaporation: Rising to the Sky

The journey begins with evaporation, the process where liquid water transforms into water vapor, an invisible gas, and rises into the atmosphere. The sun’s energy is the primary driver, heating water bodies like oceans, lakes, and rivers. You can observe a small-scale version of this when a puddle disappears on a sunny day. Billions of gallons of water evaporate from the Earth’s surface every day, with the vast majority coming from the oceans.

- Oceanic Evaporation: The largest contributor, as oceans cover over 70% of the Earth’s surface.

- Lakes and Rivers: Smaller, but still significant sources of atmospheric moisture.

- Soil Moisture: Water held in the soil also evaporates, especially after rain.

Condensation: Forming the Clouds

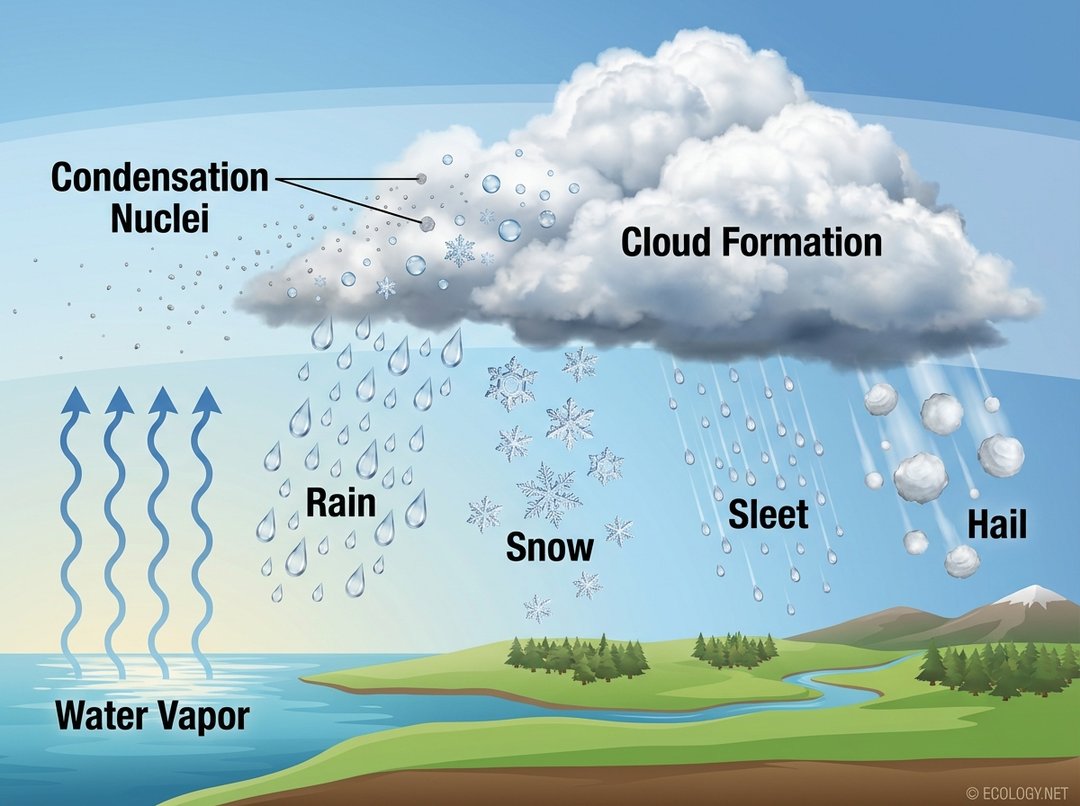

As water vapor rises higher into the atmosphere, it encounters cooler temperatures. This cooling causes the water vapor to change back into tiny liquid water droplets or ice crystals, a process called condensation. These microscopic droplets need something to condense around, which are often microscopic particles like dust, pollen, or sea salt, known as condensation nuclei. When billions of these droplets or crystals gather, they become visible as clouds.

Think of the mist that forms when you breathe out on a cold day, or the dew on grass in the morning. These are everyday examples of condensation at work.

Precipitation: Returning to Earth

Once clouds become saturated with water droplets or ice crystals, they grow too heavy to remain suspended in the air. Gravity takes over, and the water falls back to Earth in various forms of precipitation. The type of precipitation depends on the atmospheric temperature.

- Rain: Liquid water droplets that fall when temperatures are above freezing.

- Snow: Ice crystals that form and fall when temperatures are below freezing throughout the cloud and atmosphere. Each snowflake is unique, a testament to the complex atmospheric conditions during its formation.

- Sleet: Raindrops that freeze into ice pellets before reaching the ground, often occurring when a layer of freezing air is above a layer of warmer air.

- Hail: Lumps of ice that form in strong thunderstorms. Hailstones grow as they are tossed up and down within the storm cloud, accumulating layers of ice before finally falling.

Collection: Where Water Gathers

After precipitation reaches the Earth’s surface, it begins the collection phase. This phase encompasses several pathways, determining where the water goes next.

- Runoff: Water that flows over the land surface, often into streams, rivers, and eventually lakes or oceans. This surface runoff is a major force in shaping landscapes through erosion.

- Infiltration and Groundwater: Some water seeps into the ground, a process called infiltration. It fills pores in the soil and rock, becoming groundwater. This underground water can remain stored for centuries, slowly moving through aquifers, eventually emerging as springs or feeding into rivers and oceans.

- Lakes and Oceans: Large bodies of water where precipitation and runoff accumulate. These act as significant reservoirs in the water cycle.

- Ice and Snow Storage: In colder regions, precipitation can accumulate as snowpacks, glaciers, and ice caps. These act as long-term storage, releasing water slowly through melting over seasons or even millennia.

Beyond the Basics: Deeper Insights into the Hydrological Cycle

While the core stages provide a solid foundation, the water cycle involves more nuanced processes and interactions that highlight its complexity and importance.

Transpiration: Plants’ Role in the Cycle

Plants are not just passive recipients of water; they are active participants in the water cycle through a process called transpiration. Water absorbed by plant roots travels up through the stem to the leaves, where it evaporates from tiny pores called stomata into the atmosphere. This process is essentially “plant sweating” and contributes a significant amount of water vapor to the atmosphere, especially in heavily vegetated areas like rainforests.

A single large oak tree can transpire hundreds of gallons of water into the atmosphere each day, demonstrating the immense collective power of vegetation in the global water cycle.

Sublimation: From Ice to Vapor

Less commonly discussed but equally fascinating is sublimation, where ice or snow transforms directly into water vapor without first melting into liquid water. This occurs in cold, dry, and windy conditions, such as on high mountain peaks or in polar regions. While not as significant globally as evaporation, it plays a crucial role in the water balance of specific cold environments.

Groundwater Flow: The Hidden Pathways

The water that infiltrates the ground doesn’t just sit there; it moves. Groundwater slowly flows through permeable rock layers and sediment, known as aquifers. This movement can be incredibly slow, sometimes only a few feet per year, but it is a vital part of the cycle. Groundwater eventually discharges into rivers, lakes, and oceans, or is brought to the surface through springs or human-drilled wells. It represents a massive reservoir of freshwater, crucial for drinking water and irrigation.

The Human Impact on the Water Cycle

Human activities significantly influence the water cycle, often with far-reaching consequences.

- Deforestation: Removing forests reduces transpiration and increases surface runoff, leading to soil erosion and reduced groundwater recharge.

- Urbanization: Paved surfaces prevent infiltration, increasing runoff and the risk of flooding, while decreasing groundwater supplies.

- Agriculture: Irrigation practices can deplete local water sources, and agricultural runoff can introduce pollutants into waterways.

- Climate Change: Altering global temperatures affects evaporation rates, precipitation patterns (leading to more intense storms or prolonged droughts), and the melting of glaciers and ice caps, disrupting the natural balance of the cycle.

Why the Water Cycle Matters: A Lifeline for Earth

The water cycle is far more than just a scientific concept; it is the engine that drives Earth’s climate and supports all life. Its continuous operation ensures a constant supply of freshwater, regulates global temperatures, and shapes our planet’s diverse ecosystems.

- Freshwater Supply: It replenishes rivers, lakes, and groundwater, providing the water essential for drinking, agriculture, and industry.

- Climate Regulation: The movement of water, especially through evaporation and condensation, transfers heat around the globe, influencing weather and climate patterns.

- Ecosystem Support: Every habitat, from deserts to rainforests, relies on specific water cycle dynamics to thrive.

- Geological Processes: Water is a powerful agent of erosion and deposition, constantly reshaping the Earth’s surface.

Conclusion: Guardians of the Cycle

The water cycle is a testament to the dynamic and interconnected nature of our planet. From the smallest raindrop to the vast expanse of the ocean, every drop plays a role in this magnificent, life-sustaining process. As inhabitants of Earth, understanding and respecting the water cycle is paramount. Our actions have a direct impact on its delicate balance, making responsible water management and environmental stewardship not just good practice, but a necessity for the health of our planet and future generations. The endless journey of water continues, and with it, the endless story of life on Earth.