Imagine a shared resource, vital for everyone, slowly but surely deteriorating. This isn’t a dystopian novel; it’s a fundamental challenge faced by societies across the globe, a concept famously known as the “Tragedy of the Commons.” It describes a situation where individual users, acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest, deplete a shared limited resource even when it is clear that it is not in anyone’s long-term interest for this to happen. This powerful idea helps us understand everything from overfishing our oceans to air pollution in our cities.

The Core Concept: Overgrazing the Commons

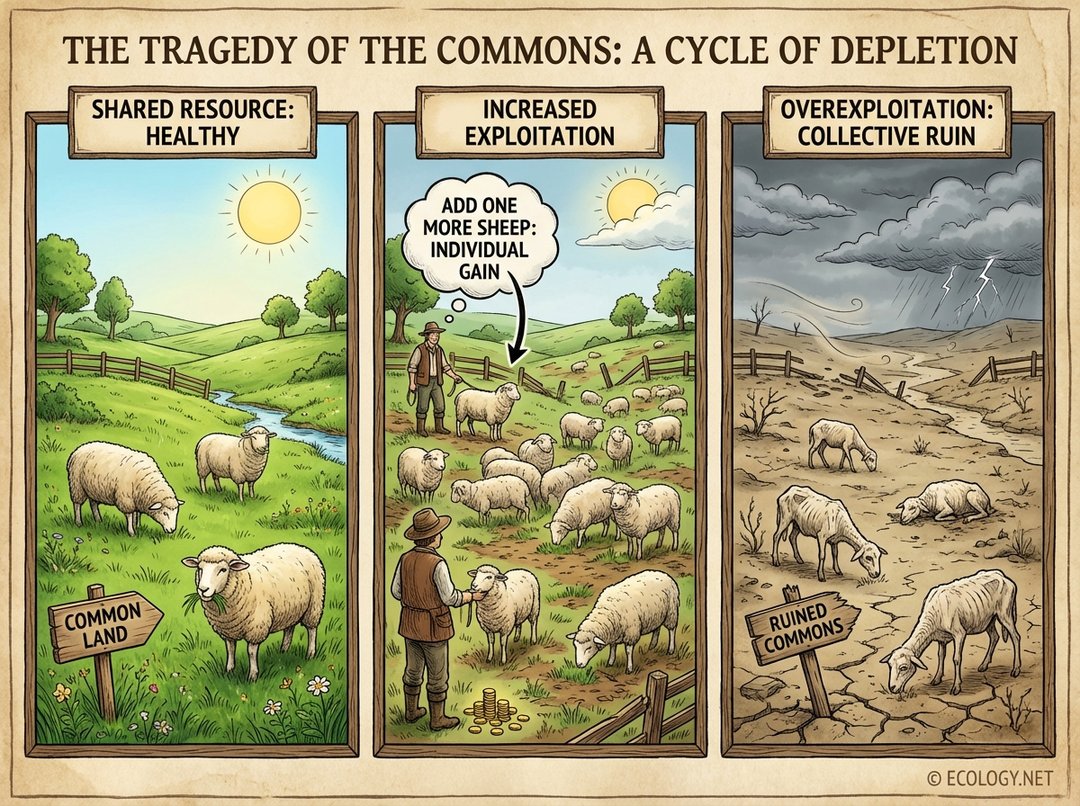

The classic illustration of the Tragedy of the Commons involves a pasture open to all herdsmen. Each herdsman, seeking to maximize their individual gain, adds more cattle to the common land. Initially, the pasture is lush and can support the animals. However, as each herdsman continues to add more animals, the cumulative effect of individual decisions begins to degrade the shared resource. The land becomes overgrazed, less productive, and eventually, barren. What was once a thriving common good turns into a desolate wasteland, harming everyone who depends on it.

This simple yet profound example highlights the core dilemma: the benefit of adding one more animal accrues entirely to the individual herdsman, while the cost of the degraded pasture is distributed among all users. This imbalance incentivizes individual exploitation, leading to collective ruin.

The Logic of Individual Gain

At the heart of the Tragedy of the Commons lies a seemingly rational decision-making process. Each individual user of a common resource asks themselves, “What is best for me?” When considering whether to take a little more from the common pool, the individual sees an immediate, tangible benefit. For instance, a fisherman catches more fish, a factory emits more pollutants, or a farmer draws more water for irrigation.

The cost, however, is diffused and often delayed. The ocean becomes slightly more depleted, the air a fraction dirtier, or the aquifer a tiny bit lower. No single individual’s action alone causes catastrophic damage, but the sum of many such “rational” individual actions inevitably leads to the degradation or collapse of the shared resource. This creates a powerful incentive to exploit the resource before others do, accelerating its depletion.

Real-World Examples of the Tragedy

The Tragedy of the Commons is not confined to ancient pastures; its principles resonate across a vast array of modern environmental and social challenges:

- Ocean Fisheries: The world’s oceans are a classic common pool resource. Individual fishing fleets, driven by economic incentives, often harvest fish beyond sustainable levels, leading to depleted stocks and threatening marine ecosystems globally.

- Atmospheric Pollution: The Earth’s atmosphere acts as a common sink for pollutants. Industrial emissions and vehicle exhaust contribute to air pollution and climate change. No single entity bears the full cost of its emissions, but everyone suffers the collective consequences.

- Water Scarcity: Shared rivers, lakes, and underground aquifers are often overdrawn for agriculture, industry, and urban use, particularly in arid regions. Each user takes what they need, often without considering the cumulative impact on the overall water supply.

- Deforestation: Forests, especially those in developing nations, are frequently exploited for timber, agriculture, and other resources. Individual actors gain from clearing land, but the collective loss includes biodiversity, carbon sinks, and vital ecosystem services.

- Traffic Congestion: Roads in urban areas can be seen as a common resource. Each driver choosing to use their car contributes to congestion, slowing down everyone, even though public transport or carpooling might be more efficient collectively.

Characteristics of Common Pool Resources

Not all shared resources are susceptible to the Tragedy of the Commons. The concept primarily applies to what are known as “common pool resources,” which possess two key characteristics:

- Non-excludability: It is difficult or costly to prevent individuals from using the resource. For example, it is hard to stop someone from breathing air or fishing in the open ocean.

- Rivalrousness: One person’s use of the resource diminishes its availability for others. If one person catches a fish, that fish is no longer available for another. If one person pollutes the air, the air quality for others is reduced.

These characteristics create the conditions where individual self-interest can lead to collective detriment.

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

Understanding the problem is the first step; finding effective solutions is the crucial next. Over the years, various approaches have been proposed and implemented to avert or reverse the Tragedy of the Commons. These generally fall into three broad categories:

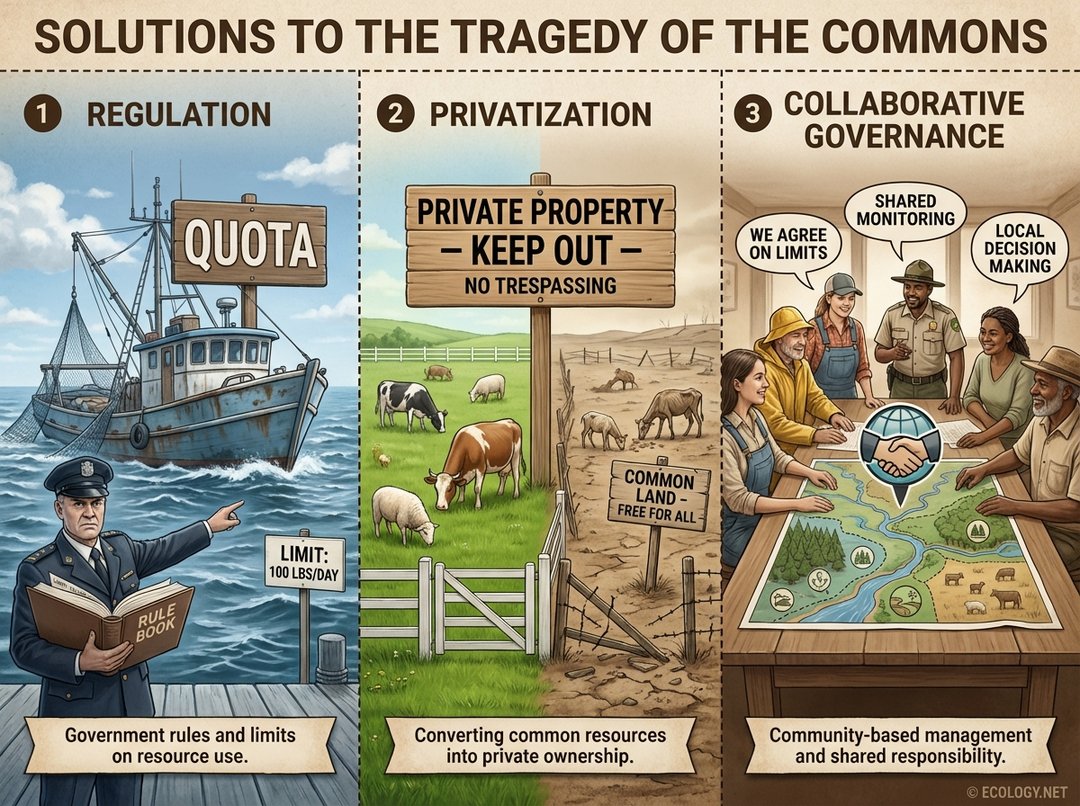

- Regulation and Government Intervention:

- Quotas and Limits: Governments can set limits on how much of a resource can be used, such as fishing quotas, emissions caps, or water usage restrictions.

- Taxes and Fees: Imposing taxes on resource extraction or pollution can internalize the external costs, making individuals or corporations pay for the collective harm they cause.

- Permits and Licenses: Requiring permits for resource use can control access and ensure sustainable practices.

- Enforcement: Effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms are vital to ensure compliance with regulations.

- Privatization:

- By converting a common resource into private property, an individual owner gains a direct incentive to manage it sustainably. A private landowner has a vested interest in maintaining the long-term health of their land because they bear the full costs and benefits of their actions.

- This approach works well for resources that can be easily divided and whose boundaries can be clearly defined and enforced, such as land or forests. However, it is often impractical or undesirable for resources like the atmosphere or open oceans.

- Collaborative Governance and Community Management:

- This approach emphasizes the role of local communities and user groups in developing and enforcing their own rules for resource management. Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom’s groundbreaking work demonstrated that communities often successfully manage common pool resources through self-organization, trust, and established norms.

- Key elements include:

- Clear boundaries of the resource and user groups.

- Rules tailored to local conditions.

- Participatory decision-making processes.

- Effective monitoring of resource conditions and user behavior.

- Graduated sanctions for rule violations.

- Accessible and low-cost conflict resolution mechanisms.

- Recognition of rights to organize by external governmental authorities.

Nuances and Criticisms

While the Tragedy of the Commons provides a powerful framework, it is important to acknowledge its nuances and criticisms. The original formulation by Garrett Hardin in 1968 often implied an inevitable decline, suggesting that only top-down control or privatization could save common resources. However, subsequent research, particularly by Elinor Ostrom, challenged this deterministic view.

Ostrom’s work highlighted that humans are not always trapped in an inescapable tragedy. Instead, many communities around the world have successfully managed common pool resources for centuries through complex systems of self-governance, cooperation, and social norms. These systems often involve intricate rules, monitoring, and enforcement mechanisms developed and maintained by the users themselves.

Factors like trust, communication, shared cultural values, and the ability to design and adapt rules to local conditions play a critical role in whether a common resource thrives or succumbs to tragedy. The size of the group, the nature of the resource, and the presence of external pressures also significantly influence outcomes. Therefore, while the potential for tragedy is real, it is not an unavoidable fate. Human ingenuity and collective action can, and often do, provide pathways to sustainable resource management.

Conclusion

The Tragedy of the Commons remains one of the most compelling and relevant concepts in environmental science, economics, and public policy. It illuminates the inherent tension between individual self-interest and collective well-being, particularly when dealing with shared, finite resources. From the air we breathe to the water we drink, and the biodiversity that sustains us, understanding this tragedy is crucial for fostering sustainable practices.

By recognizing the mechanisms that drive resource depletion and by exploring diverse solutions ranging from robust regulations to innovative community-led governance, societies can move beyond the brink of collective ruin. The challenge lies in finding the right balance of incentives, rules, and cooperation that encourages responsible stewardship of our planet’s invaluable common resources for generations to come.