The Living Earth: Unlocking the Secrets of Soil Fertility

Beneath our feet lies a world teeming with life and potential, a foundation for all terrestrial ecosystems and human civilization: the soil. More than just dirt, healthy soil is a complex, dynamic system, and its fertility is the cornerstone of robust plant growth, bountiful harvests, and a thriving planet. Understanding soil fertility is not merely an academic exercise; it is a vital step towards sustainable agriculture, environmental stewardship, and ensuring food security for generations to come.

What Exactly is Soil Fertility?

At its heart, soil fertility refers to the capacity of soil to sustain plant growth by providing essential plant nutrients and favorable conditions for growth. It is a delicate balance of physical, chemical, and biological properties that work in concert to create an optimal environment for roots to flourish. Think of it as the soil’s inherent ability to be a good host for plants.

Key Components of Soil Fertility

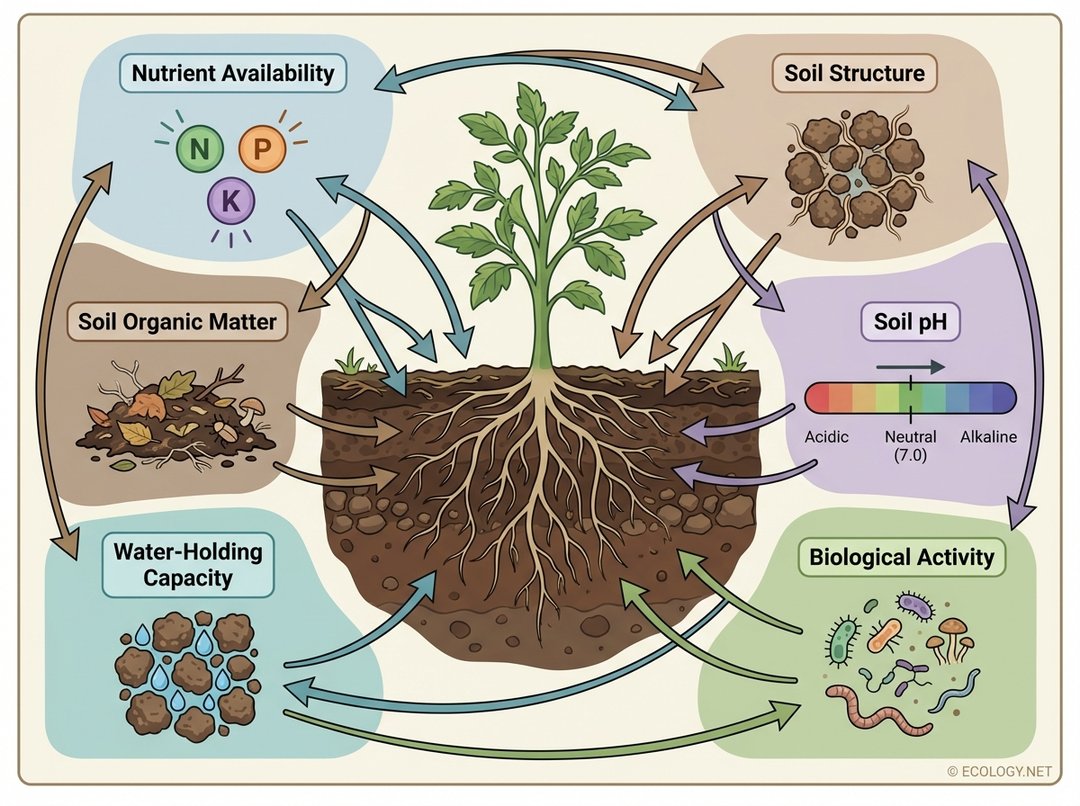

Soil fertility is not a single factor but a symphony of interconnected elements. To truly appreciate its complexity, we can break it down into six fundamental components, each playing a crucial role in supporting plant life.

- Nutrient Availability: Plants require a steady supply of macronutrients like nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), along with various micronutrients. Fertile soil acts as a reservoir, holding these nutrients in forms that plants can readily absorb through their roots.

- Soil Structure: This refers to how soil particles (sand, silt, clay) clump together to form aggregates. Good soil structure creates pore spaces for air and water movement, crucial for root respiration and microbial activity. Imagine a well-aerated sponge versus a compacted brick.

- Soil Organic Matter (SOM): The decomposed remains of plants, animals, and microbes. SOM is the lifeblood of fertile soil, improving structure, increasing water retention, and acting as a slow-release bank for nutrients. It is the engine that drives many soil processes.

- Soil pH: A measure of soil acidity or alkalinity. The pH level dictates the availability of nutrients to plants. Most plants thrive in a slightly acidic to neutral range (pH 6.0-7.0), where nutrient uptake is optimized.

- Water-Holding Capacity: Fertile soil can absorb and retain sufficient moisture for plant growth, releasing it gradually as needed. This prevents both waterlogging and drought stress, ensuring a consistent supply of hydration.

- Biological Activity: The unseen workforce of the soil, including bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, and earthworms. These organisms decompose organic matter, cycle nutrients, improve soil structure, and protect plants from disease.

This illustrative diagram beautifully captures the dynamic interplay between these six core ingredients. Each component supports the others, creating a robust system where plant roots can thrive, absorbing the necessary elements for vigorous growth. A deficiency in one area can cascade, impacting the overall health and productivity of the soil.

The Unseen Architects: Biological Activity and the Soil Food Web

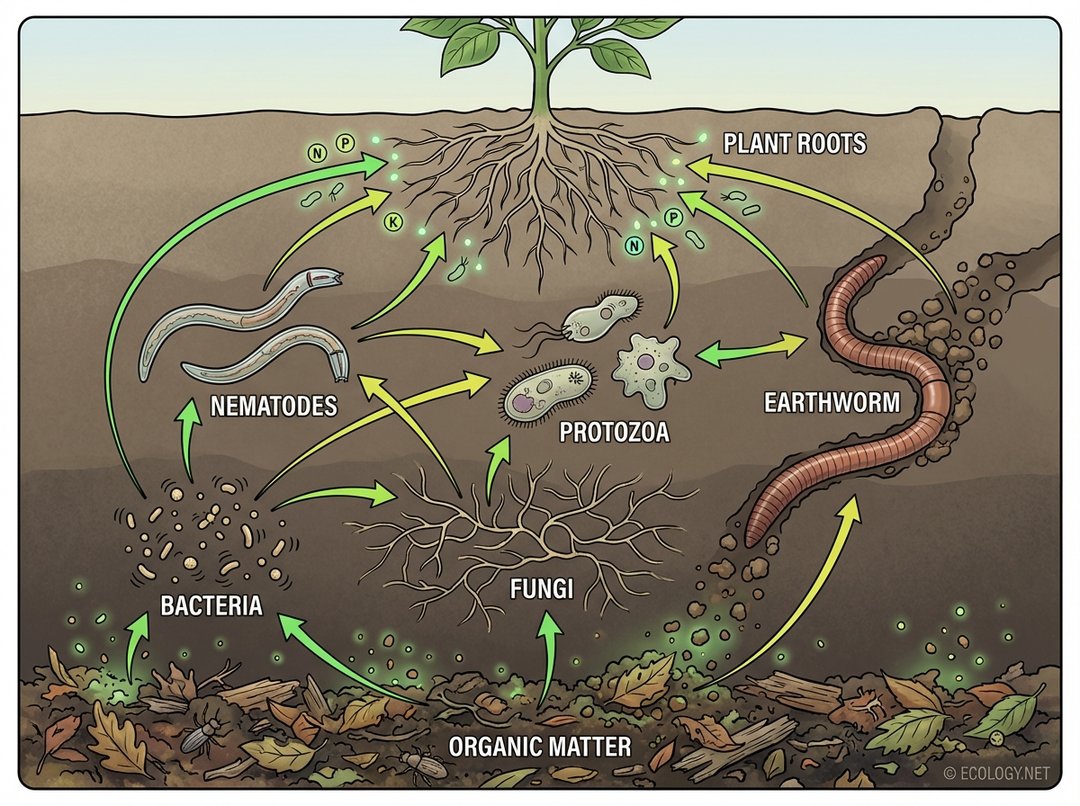

While nutrient levels and soil structure are tangible, the biological activity within the soil often remains an invisible marvel. Yet, it is arguably the most dynamic and crucial component of soil fertility. This bustling underground ecosystem, often referred to as the “Soil Food Web,” is a complex network of organisms that interact to cycle nutrients, build soil structure, and maintain soil health.

Exploring the Soil Food Web

The soil food web is a hierarchical system, much like a terrestrial food chain, but operating within the confines of the soil. It begins with the primary producers and decomposers and extends to various levels of consumers.

- Organic Matter: The Foundation

The base of the food web consists of dead plant and animal residues, root exudates, and other organic materials. This is the energy source that fuels the entire system. - First Trophic Level: Decomposers

- Bacteria: Microscopic single-celled organisms that are the primary decomposers of simple organic compounds. They play a vital role in nitrogen fixation and nutrient cycling.

- Fungi: These organisms, including yeasts, molds, and mushrooms, are crucial decomposers of more complex organic materials like cellulose and lignin. Mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, extending their reach for water and nutrients.

- Second Trophic Level: Grazers and Predators of Decomposers

- Protozoa: Single-celled organisms that consume bacteria, releasing excess nitrogen in a form available to plants.

- Nematodes: Microscopic roundworms. While some are plant parasites, many are beneficial, feeding on bacteria, fungi, or other nematodes, further contributing to nutrient cycling.

- Higher Trophic Levels: Larger Invertebrates and Predators

- Earthworms: Often called “ecosystem engineers,” earthworms burrow through the soil, creating channels for air and water. They consume organic matter and soil, mixing it and excreting nutrient-rich castings that improve soil structure and fertility.

- Arthropods: Insects, mites, and other creatures that shred organic matter, creating smaller pieces for microbial decomposition, or prey on other soil organisms.

The constant feeding and decomposition within this web release nutrients from organic matter into forms that plants can absorb. Without this intricate biological activity, even nutrient-rich soil would struggle to provide for plants.

This detailed diagram illustrates the complex interactions within the soil food web. From the decomposition of organic matter by bacteria and fungi to the grazing by protozoa and nematodes, and the vital work of earthworms, every organism plays a part in the continuous cycle of life and nutrient exchange that ultimately benefits the plant.

Maintaining and Improving Soil Fertility: Practical Steps for a Healthier Earth

Understanding the components of soil fertility is the first step; the next is actively working to enhance and preserve it. Whether you are a large-scale farmer, a home gardener, or simply someone interested in ecological health, there are numerous practices that can significantly boost soil fertility and lead to more resilient ecosystems.

Proven Strategies for Soil Enhancement

- Crop Rotation: This involves planting different crops in a sequence on the same piece of land over several seasons. For example, following a nitrogen-demanding crop like corn with a nitrogen-fixing legume like clover or beans.

- Benefits: Prevents nutrient depletion, breaks pest and disease cycles, improves soil structure, and can reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Composting: The controlled decomposition of organic materials (food scraps, yard waste) into a nutrient-rich soil amendment called compost.

- Benefits: Adds organic matter, improves soil structure, enhances water retention, provides a slow release of nutrients, and introduces beneficial microbes.

- Cover Cropping: Planting non-cash crops (e.g., rye, vetch, clover) during fallow periods between main crops. These crops are typically not harvested but are tilled into the soil or left to decompose.

- Benefits: Prevents soil erosion, suppresses weeds, adds organic matter, fixes nitrogen (if legumes are used), and improves soil structure.

- No-Till or Minimum Tillage Farming: A practice where the soil is left undisturbed from harvest to planting, with crop residues remaining on the surface.

- Benefits: Reduces soil erosion, conserves soil moisture, increases soil organic matter, and protects soil structure and the soil food web.

- Balanced Fertilization: Applying nutrients based on soil tests to meet specific plant needs, avoiding over-application which can harm soil life and lead to nutrient runoff.

- Benefits: Ensures optimal plant nutrition without detrimental environmental impacts.

- Manure and Biochar Application: Incorporating well-rotted animal manure or biochar (a charcoal-like substance) can significantly boost organic matter, nutrient content, and water retention.

- Benefits: Long-term soil improvement, carbon sequestration.

This image vividly illustrates several key practices for improving soil fertility in an agricultural setting. From the strategic planting of different crops in rotation to the careful management of compost, the protective blanket of cover crops, and the innovative approach of no-till farming, these methods demonstrate a commitment to nurturing the soil for long-term productivity and ecological health.

The Long-Term Vision: Sustainable Soil Management

The health of our soil is inextricably linked to the health of our planet and the well-being of its inhabitants. By adopting practices that enhance soil fertility, we are not just growing better crops; we are fostering biodiversity, mitigating climate change by sequestering carbon, improving water quality, and building more resilient food systems. Sustainable soil management is an investment in the future, ensuring that the living earth continues to provide for generations to come.

Conclusion: The Enduring Value of Fertile Soil

Soil fertility is a complex, dynamic, and utterly essential concept. It encompasses the physical, chemical, and biological attributes that allow soil to sustain life, from microscopic organisms to towering trees and the food we eat. By understanding its key components, appreciating the intricate dance of the soil food web, and implementing thoughtful management practices, we can all contribute to a healthier, more productive, and more sustainable world. The vitality of our planet begins with the vitality of its soil.