Rivers, the lifeblood of our planet, are far more than just flowing water. They are dynamic ecosystems, powerful sculptors of landscapes, and vital arteries connecting diverse environments. From their humble mountain springs to their grand oceanic deltas, rivers tell a story of constant change, intricate ecological relationships, and profound influence on human civilization.

Understanding rivers means appreciating their journey, the unique habitats they create, and the critical role they play in the global ecosystem. This exploration will delve into the fascinating world of rivers, uncovering their physical characteristics, the diverse life they support, and the challenges they face in an ever-changing world.

The Anatomy of a River: A Journey from Source to Sea

Every river embarks on an incredible journey, transforming from a tiny trickle into a mighty waterway. This journey shapes the land around it, creating a variety of distinctive features along its path.

The life of a river begins at its source, often high in mountains or hills, where melting snow, glaciers, or persistent rainfall feed small streams. These initial streams, known as tributaries, gradually merge, growing in volume and power as they flow downhill. The combined flow forms the main channel of the river.

As the river descends from steeper terrain to flatter plains, its character changes dramatically. The fast, turbulent flow of the upper reaches gives way to a slower, more meandering course. Here, the river begins to carve graceful curves known as meanders. These bends are not static; the river continuously erodes the outer bank and deposits sediment on the inner bank, causing the meanders to migrate across the landscape.

Sometimes, a meander loop becomes so exaggerated that the river cuts across its narrow neck during a flood. When this happens, the old meander is abandoned, forming a crescent-shaped body of water called an oxbow lake. Adjacent to these meandering rivers, particularly in their middle and lower courses, lie broad, flat areas known as floodplains. These fertile lands are periodically inundated during floods, depositing nutrient-rich sediments that have historically supported agriculture.

Finally, as the river approaches its ultimate destination, usually an ocean, sea, or large lake, its velocity slows significantly. The reduced energy causes the river to deposit the vast amounts of sediment it has carried downstream. This deposition forms a complex network of distributaries, channels, and islands, creating a fan-shaped landform known as a delta. Deltas are incredibly rich ecosystems, supporting a wealth of biodiversity and human populations.

River Morphology: Shaping the Land

The continuous interaction between water flow, sediment transport, and the underlying geology dictates a river’s morphology. This dynamic process is responsible for the diverse landscapes we see along river courses.

- Erosion: In its upper reaches, a river’s primary role is erosion. The fast-moving water, often carrying abrasive sediment, carves out V-shaped valleys and rapids. Think of the Grand Canyon, a monumental testament to riverine erosion.

- Transportation: Rivers are nature’s conveyor belts, transporting vast quantities of sediment, from fine silt and sand to pebbles and boulders, from upstream to downstream. The amount and type of sediment a river carries depend on its velocity and volume.

- Deposition: As a river loses energy, it begins to deposit its sediment load. This process is crucial for forming floodplains, point bars within meanders, and ultimately, deltas. The fertile soils of the Nile Delta, for instance, are a direct result of centuries of riverine deposition.

Life in Different River Zones: A Microcosm of Biodiversity

Rivers are not uniform environments; they are mosaics of diverse habitats, each supporting a unique community of organisms. The physical characteristics of the river, such as water velocity, depth, and substrate type, create distinct zones that aquatic life has adapted to exploit.

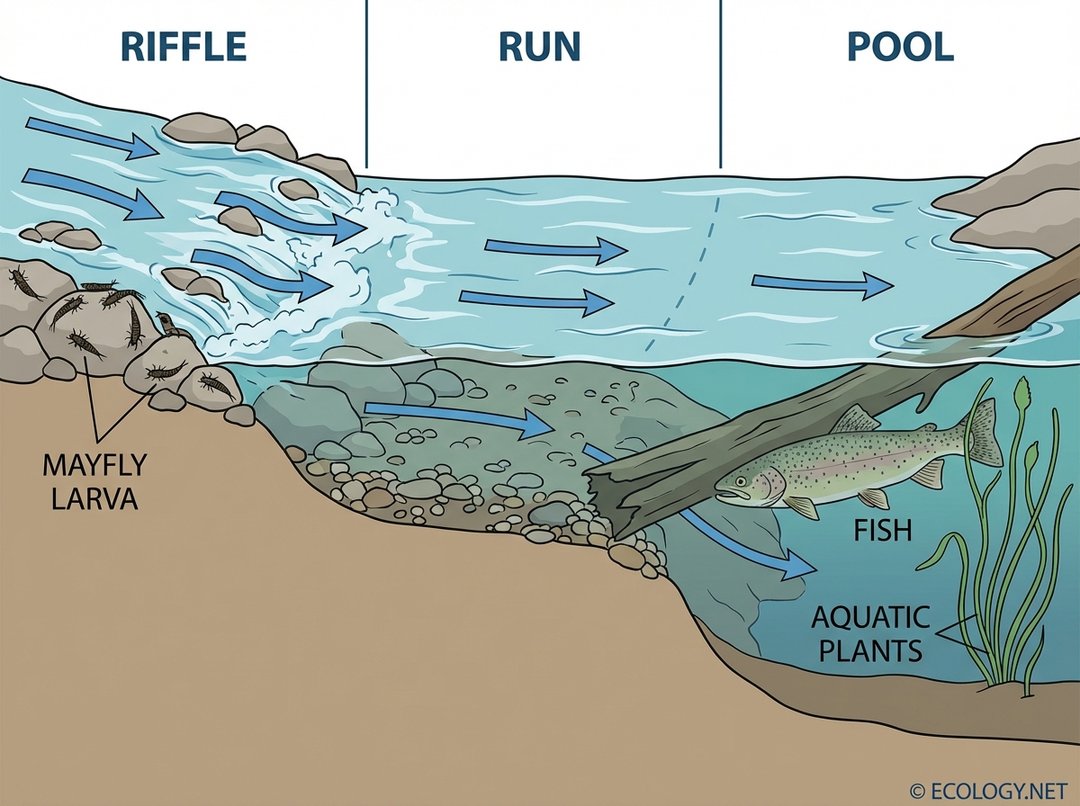

Ecologists often categorize river habitats into three primary zones:

- Riffles: These are shallow, fast-flowing sections of a river where the water tumbles over rocks and gravel. The high oxygen levels and abundant food (algae and detritus) make riffles ideal habitats for specialized invertebrates. Organisms here often have flattened bodies, suckers, or hooks to cling to rocks and avoid being swept away. Examples include mayfly larvae, caddisfly larvae, and stonefly nymphs.

- Pools: Deeper, slower-moving sections of a river, often found on the inside bends of meanders or in depressions. Pools provide refuge from strong currents, especially during floods, and are important resting and feeding areas for fish. Aquatic plants can often establish themselves in the calmer waters of pools, providing additional habitat and food sources. Fish like trout and bass often seek out pools.

- Runs: These are intermediate sections, characterized by moderate depth and flow velocity, often with a smoother surface than riffles. Runs connect riffles and pools, serving as important transitional zones for many aquatic species.

Adaptations for River Life

The organisms inhabiting rivers display an astonishing array of adaptations to thrive in their dynamic environments:

- Streamlined Bodies: Many fish and aquatic insects have torpedo-shaped bodies that reduce drag in fast currents.

- Attachment Mechanisms: Invertebrates in riffles often possess suckers (e.g., blackfly larvae) or hooks (e.g., caddisfly larvae) to anchor themselves to rocks.

- Behavioral Adaptations: Fish may seek shelter behind rocks or in slower currents to conserve energy. Some species migrate upstream to spawn, demonstrating incredible endurance against the current.

- Oxygen Uptake: Organisms in fast-flowing, oxygen-rich waters often have highly efficient gills or specialized respiratory structures.

The Broader Ecological Significance of Rivers

Beyond their physical beauty and the immediate habitats they provide, rivers are cornerstones of global ecosystems, offering a multitude of essential services.

Biodiversity Hotspots

Rivers and their associated wetlands are among the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth. They support a vast array of species, from microscopic algae and bacteria to large mammals and birds. Freshwater fish alone account for nearly half of all known fish species, despite freshwater habitats covering less than 1% of the Earth’s surface. Iconic species like salmon, sturgeon, otters, and kingfishers all depend on healthy river systems.

Ecosystem Services

Rivers provide invaluable ecosystem services that benefit both nature and humanity:

- Water Supply: Rivers are a primary source of drinking water for billions of people worldwide, as well as for agriculture and industry.

- Nutrient Transport: They transport essential nutrients and organic matter, enriching downstream ecosystems and floodplains.

- Habitat Provision: Rivers provide critical habitats, breeding grounds, and migratory corridors for countless species.

- Flood Regulation: Healthy floodplains and riparian zones can absorb excess water during floods, reducing damage to human settlements.

- Climate Regulation: Rivers play a role in the global water cycle, influencing local and regional climates.

The Importance of Riparian Zones

The land immediately adjacent to a river, known as the riparian zone, is a crucial transitional area between aquatic and terrestrial environments. These zones, often characterized by lush vegetation, perform vital functions:

- Bank Stabilization: Plant roots hold soil in place, preventing erosion and maintaining riverbank integrity.

- Water Filtration: Riparian vegetation filters pollutants and excess nutrients from runoff before they enter the river, improving water quality.

- Shade and Temperature Regulation: Overhanging trees provide shade, keeping water temperatures cooler, which is vital for many aquatic species, especially in warmer climates.

- Habitat and Food: Riparian zones offer habitat for terrestrial wildlife and contribute organic matter (leaves, insects) to the river, providing food for aquatic organisms.

Rivers in Peril: Threats and Conservation

Despite their immense importance, rivers globally face unprecedented threats from human activities. Understanding these challenges is the first step towards effective conservation.

Major Threats to River Ecosystems

- Pollution: Industrial discharge, agricultural runoff (pesticides, fertilizers), untreated sewage, and plastic waste all degrade water quality, harming aquatic life and rendering water unsafe for human use.

- Habitat Degradation and Loss:

- Dams and Weirs: These structures alter natural flow regimes, block fish migration routes, change water temperature, and trap sediment, significantly impacting downstream ecosystems.

- Channelization: Straightening rivers for flood control or navigation destroys natural meanders, riffles, and pools, simplifying habitats and reducing biodiversity.

- Riparian Zone Destruction: Removal of vegetation along riverbanks for development or agriculture leads to increased erosion, sedimentation, and loss of critical habitat.

- Over-extraction of Water: Excessive withdrawal of water for irrigation, industry, and urban use can reduce river flows to critically low levels, drying up sections of rivers and devastating aquatic communities.

- Climate Change: Altered precipitation patterns, increased frequency of extreme floods and droughts, and rising water temperatures all pose significant threats to river ecosystems and the species that depend on them.

- Invasive Species: Non-native species introduced to river systems can outcompete native species, disrupt food webs, and alter habitats, leading to declines in biodiversity.

The Imperative of River Conservation

Protecting and restoring rivers is a global imperative. Conservation efforts often focus on a multi-faceted approach:

- Sustainable Water Management: Implementing policies that ensure equitable and efficient water use, minimizing over-extraction, and promoting water conservation.

- Pollution Control: Stricter regulations on industrial and agricultural discharges, improved wastewater treatment, and public awareness campaigns to reduce littering.

- Habitat Restoration: Removing obsolete dams, restoring natural meanders, replanting riparian vegetation, and creating fish passages around necessary barriers.

- Protected Areas: Establishing and managing protected areas along river corridors to safeguard critical habitats and biodiversity.

- Community Engagement: Involving local communities in river monitoring, clean-up efforts, and sustainable practices.

The health of our rivers is inextricably linked to the health of our planet and our own well-being. They are not merely conduits for water but vibrant, living systems that deserve our utmost respect and protection.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Rivers

Rivers are truly magnificent natural wonders, embodying the power of water to shape landscapes and sustain life. From the intricate dance of erosion and deposition that carves their paths to the delicate balance of life within their waters, every aspect of a river system is a testament to nature’s complexity and resilience.

As we continue to navigate the challenges of a changing world, the importance of healthy rivers becomes ever more apparent. They are vital for our water supply, our food security, and the incredible biodiversity that enriches our planet. By understanding, appreciating, and actively working to protect these invaluable arteries of the Earth, humanity can ensure that the life-giving flow of rivers continues for generations to come.