Understanding Resilience: The Unseen Strength of Systems

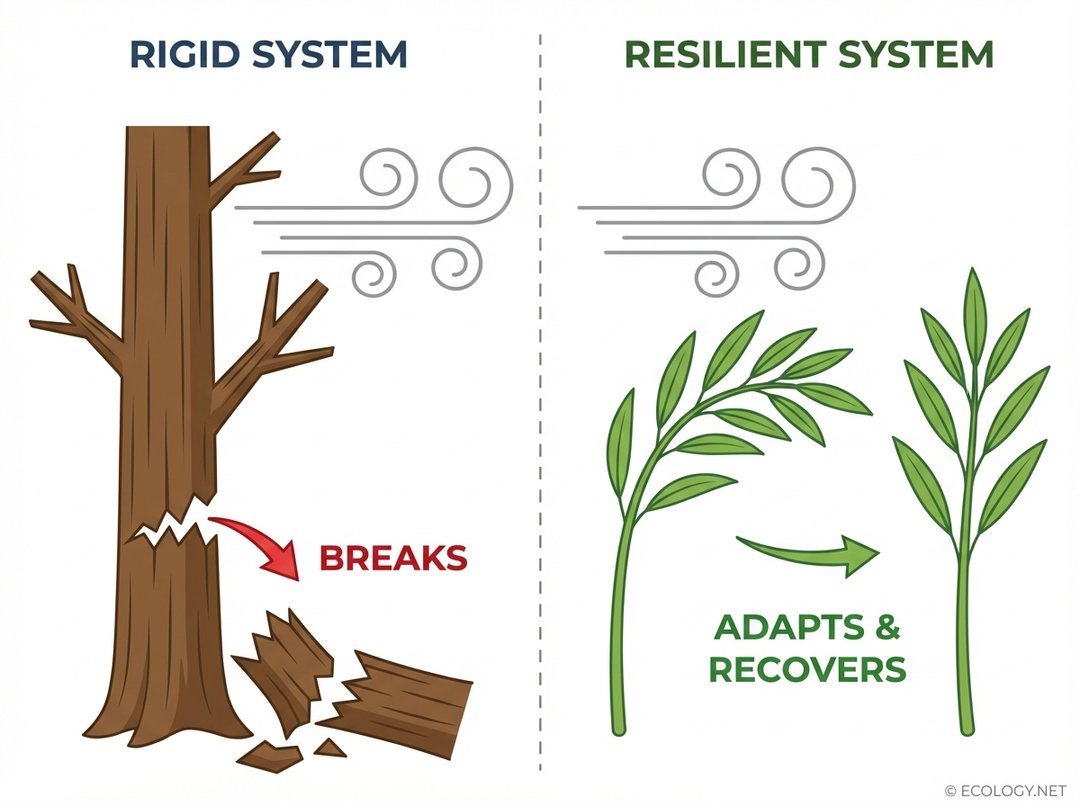

Imagine a mighty oak tree, standing tall and unyielding against a fierce storm. It resists the wind with all its strength, but eventually, a powerful gust snaps its trunk. Now, picture a young willow sapling nearby. It bends, sways, and almost touches the ground under the same gale, yet when the storm passes, it springs back upright, intact and ready to continue growing. This vivid contrast illustrates a fundamental concept crucial to understanding how natural and human systems endure and thrive: resilience.

Resilience is more than just toughness. It is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance, to reorganize while undergoing change, and to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks. It is the ability not just to survive a shock, but to adapt and recover, often emerging stronger or better suited to future challenges. In an increasingly unpredictable world, understanding and fostering resilience is paramount.

Consider the difference between a rigid structure that breaks under pressure and a flexible one that bends and recovers. This distinction is vital.

Why Resilience Matters in a Changing World

The concept of resilience extends far beyond individual trees. It applies to everything from a single organism’s immune system to vast global ecosystems, and even to human societies and economies. In an era marked by rapid environmental shifts, climate change, habitat loss, and socio economic volatility, the ability of systems to withstand and recover from shocks is not merely desirable; it is essential for long term sustainability and well being.

For ecosystems, resilience means the difference between a forest recovering from a wildfire and transforming into a barren landscape. For communities, it means the ability to rebuild and thrive after a natural disaster, rather than collapsing. For economies, it signifies the capacity to absorb financial crises without spiraling into prolonged depressions. Embracing resilience helps us move beyond simply reacting to problems and instead build systems that are inherently robust and adaptive.

The Core Components of Resilience: Nature’s Blueprint

Ecological science has identified several key components that contribute to a system’s resilience. These are not isolated factors but interconnected elements that work in concert to enhance a system’s ability to cope with disturbance. Understanding these components provides a blueprint for fostering resilience in both natural and human engineered systems.

The three most critical components are:

- Diversity: The Wealth of Options

Diversity refers to the variety of elements within a system. In an ecosystem, this means a wide range of species, genetic variations within those species, and different types of habitats. A diverse system has more options and pathways to respond to change. For example, a forest with many different tree species is less vulnerable to a single pest or disease outbreak than a monoculture plantation. If one species is affected, others can continue to perform vital functions, ensuring the overall health of the forest.

A diverse ecosystem is like a well stocked toolbox; the more tools you have, the better equipped you are to fix unexpected problems.

In human systems, diversity can mean a variety of skills in a workforce, different energy sources in a power grid, or multiple food supply chains. Each adds a layer of protection against unforeseen disruptions.

- Redundancy: Safety in Numbers

Redundancy means having multiple components that can perform similar functions. It is about having backup systems. In an ecosystem, if several different species of pollinators visit the same flower, the ecosystem is more resilient to the decline of any single pollinator species. The other species can step in and continue the essential task of pollination, preventing a collapse in plant reproduction.

Think of it as having multiple spare tires for a long journey. While you might only need one, having several ensures you are prepared for multiple punctures. In infrastructure, redundancy might involve having multiple routes for data transmission or several water treatment plants serving a city. This ensures that if one component fails, the system can still operate effectively.

- Connectivity: The Web of Life

Connectivity refers to the links and flows between different parts of a system. In nature, this includes the movement of species between habitats, the flow of water through river networks, or the dispersal of seeds and genes. Well connected ecosystems allow organisms to move to more favorable conditions when their current habitat changes, facilitating adaptation and recovery.

For instance, wildlife corridors allow animals to migrate between fragmented forest patches, maintaining genetic diversity and enabling populations to recolonize areas after disturbances. Rivers connecting different wetlands ensure the spread of aquatic species and the replenishment of water resources. In human systems, connectivity can be seen in robust communication networks, efficient transportation systems, or strong social ties within a community, all of which facilitate rapid response and recovery during crises.

Resilience in Action: Nature’s Masterclass

Nature provides countless examples of resilience in action:

- Forests and Fire: Many forest ecosystems, particularly those adapted to fire, demonstrate remarkable resilience. After a wildfire, certain tree species release seeds that only germinate with heat, while others resprout from their roots. The ash enriches the soil, and a new cycle of growth begins, often leading to a more diverse and vigorous forest over time.

- Coral Reefs: While highly sensitive, some coral reefs can show resilience after bleaching events. If ocean temperatures return to normal quickly, corals can recover their symbiotic algae and regain their vibrant colors and functions. The presence of diverse coral species and healthy fish populations that graze on algae can aid this recovery process.

- Wetlands: These vital ecosystems are natural sponges. They absorb excess water during floods, protecting inland areas, and slowly release it during droughts. Their diverse plant life filters pollutants, maintaining water quality. This inherent capacity to absorb and process disturbances makes wetlands incredibly resilient.

Building Resilience: A Path Forward

Understanding the principles of resilience is not just an academic exercise; it offers practical insights for managing our world. Whether we are designing urban landscapes, managing natural resources, or planning for future uncertainties, fostering diversity, redundancy, and connectivity can significantly enhance our ability to cope with change.

Strategies for building resilience include:

- Protecting Biodiversity: Conserving a wide range of species and genetic variations strengthens ecosystems against shocks.

- Restoring Ecosystems: Replanting native forests, restoring wetlands, and rehabilitating degraded habitats can enhance natural resilience.

- Creating Green Infrastructure: Incorporating natural systems like rain gardens, green roofs, and permeable surfaces into urban planning can help cities absorb stormwater and mitigate heat.

- Diversifying Resources: Relying on multiple sources for energy, food, and water reduces vulnerability to disruptions in any single source.

- Strengthening Social Networks: Fostering community bonds and local support systems can significantly improve a community’s ability to respond to and recover from crises.

Beyond the Basics: Understanding Resilience Dynamics

For a deeper understanding, it is important to recognize that resilience is not static. Systems can shift between different states of resilience. A system might be highly resilient to small disturbances but cross a “threshold” where a larger shock pushes it into an entirely different, often less desirable, state. For example, overfishing can push a healthy marine ecosystem past a threshold, leading to a permanent shift to an algal dominated state from which it cannot easily recover.

Ecologists also study “adaptive cycles,” which describe how systems move through phases of growth, conservation, release (disturbance), and reorganization. Understanding these cycles helps us anticipate when systems might be most vulnerable or most ripe for transformative change. It emphasizes that change is an inherent part of resilient systems, and the ability to reorganize effectively after a disturbance is key.

Conclusion: Embracing the Adaptive Future

Resilience is a dynamic and multifaceted concept, offering a powerful lens through which to view the challenges and opportunities of our interconnected world. It moves us beyond simply preventing problems to actively designing and nurturing systems that can adapt, recover, and even thrive in the face of inevitable change. By embracing the principles of diversity, redundancy, and connectivity, we can build a more robust, sustainable, and adaptive future for both nature and humanity. The willow sapling’s quiet strength offers a profound lesson: true strength lies not in rigidity, but in the capacity to bend and recover.